With their precision engineering and distinctive white waveguides, the One series put Amphion on the studio map. And now they’ve got even better.

I first wrote about Amphion monitors in these pages over 10 years ago, when I reviewed the One15 and One18 models (along with an Amphion power amplifier). That speaker has now been revised, with a new tweeter and a re‑engineered crossover, to become the One18X.

I first wrote about Amphion monitors in these pages over 10 years ago, when I reviewed the One15 and One18 models (along with an Amphion power amplifier). That speaker has now been revised, with a new tweeter and a re‑engineered crossover, to become the One18X.

The One18X is a relatively small monitor, so nearfield installation is not likely to provide any dimensional challenges. Its front panel carries a nominally 165mm‑diameter bass/mid driver and a 25mm dome tweeter, the latter mounted at the mouth of a generous and matte‑white curved waveguide. The waveguide is comparable in size with that of the bass/mid driver. Both the tweeter and bass/mid driver feature aluminium diaphragms, and they are integrated via a passive crossover at an unusually low 1600Hz. The One18X’s advertised bandwidth is 45Hz to 55kHz ±3dB, and its sensitivity 85dB at 1m for 2.83V (1W at 8Ω). It’s specified to offer the amplifier a nominally 8Ω load, but as we’ll see, passive speaker impedance is a subject generously laced with complexities.

Around the back we find an auxiliary bass radiator (ABR), also equipped with an aluminium diaphragm, and some input terminals that can accept 4mm plugs, bare wires or spade connectors. The cabinet is finished in a dark grey textured paint and is constructed of internally braced MDF. It feels both extremely rigid and non‑resonant. While I’m on the subject of cabinets, I’ve always really admired the classically ‘Scandinavian’ Amphion industrial design aesthetic. The combination of visual simplicity with classy finishes and beautifully judged proportions presses all the right buttons for me.

Passive Voice

Bar the One25A, all Amphion monitors are passive. I’m sure the vast majority of readers appreciate the difference between active and passive monitors, but just in case, here’s a one‑sentence explanation. Rather than incorporating multi‑driver amplification and line‑level (or DSP‑based) crossover filtering within their cabinet, as do active monitors, passive monitors contain a crossover filter network that operates at power level, and are driven by external amplification. I’m not going to get into the pros and cons of the active and passive principles now, except to say that we in the pro‑audio sector have come to expect monitors to be active, and perhaps to see passive monitors as maybe equivalent to a slightly weird relative: that uncle who lives out in the middle of nowhere with seven cats and is only ever mentioned in hushed tones. But of course, just as Uncle Colin might well be living his best life and having a fabulous time, passive monitors can work extremely effectively — as evidenced by countless very satisfied Amphion users. Furthermore, wearing my speaker engineer hat, I have a soft spot for passive monitors; to my mind there’s more creative artistry inherent in their design. Active speakers, from a design perspective anyway, can seem a touch ‘paint by numbers’ I feel.

Another Amphion feature is the generous tweeter waveguide. In electro‑acoustic terms, the waveguide is perhaps more significant than the passive format, because it defines some of the electro‑acoustic design parameters at a more fundamental level. A decade ago, when I first wrote about Amphion monitors, big tweeter waveguides were relatively unusual. These days, though, there are many more such devices to be seen adorning the front panels of monitors, which suggests the arguments in their favour have gained some traction. So what are the arguments?

Guiding Light

Any conventional two‑way speaker, in which the full audio band is covered by a bass/mid driver and a tweeter, potentially incorporates a challenge: engineering a bass/mid driver that extends high enough in frequency to integrate with a tweeter that extends low enough is inherently difficult. If the bass/mid driver has a diaphragm large enough to reproduce low frequencies at a reasonable volume level, it will become significantly directional at the top end of its band; and at said top end of the band, a large diaphragm will have stopped moving as a whole and be working in a somewhat chaotic, resonant mode. The tweeter issue is that if the diaphragm is small and light enough to reach up to 20kHz with acceptably wide dispersion, it might struggle to reach low enough in frequency to integrate with the already bandwidth‑challenged bass/mid driver whilst retaining acceptable power handling and distortion levels. Furthermore, even when a bass/mid driver and tweeter are successfully integrated, there is likely to be a significant dispersion mismatch between them. The dispersion of the tweeter at the bottom of its band will be inherently wider than the dispersion of the bass/mid driver at the top of its band. The result of that will be potentially audible non‑linearity in the off‑axis response.

Adding a waveguide to a tweeter offers a potential fix. Firstly, the waveguide modifies the inherent radiation impedance mismatch between a tweeter diaphragm and the air, and the result of that is a very significant increase in tweeter radiation efficiency. A waveguide can add around 10dB to tweeter sensitivity, and that allows its operational band to be extended very usefully downwards because its overall workload is significantly reduced. Secondly, tweeter dispersion, rather than being defined by the diaphragm diameter, will be defined at lower frequencies by the waveguide diameter, and if that is comparable to the diameter of the bass/mid driver, they will have similar dispersion. So the dispersion mismatch between bass/mid driver and tweeter goes away.

A further benefit is that the increased sensitivity of the tweeter enables the crossover frequency to be lowered. This both relieves the bass/mid driver from duty at the top end of its range where the going gets tough, and, again, helps with the dispersion mismatch, because the bass/mid driver is low‑pass filtered earlier (where it is less directional) and where the wavelength is longer (so path‑length differences between the drivers and the listener result in less phase difference).

Loading...

Instead of a port, the One18X loads its bass driver with an ABR, or auxiliary bass radiator, mounted on the rear of the cabinet.The final signature Amphion characteristic is their use of auxiliary bass radiators for bass loading (the term ‘loading’ comes from the idea that you ‘load’ the bass driver diaphragm with the mass and compliance of the air in the cabinet). The ABR technique is closely related to ‘simple’ port tube reflex loading (ABR is in fact a form of reflex loading), but rather than employ a tuned port to extend the bass driver output, a driver diaphragm and suspension (with no motor system) is used.

Instead of a port, the One18X loads its bass driver with an ABR, or auxiliary bass radiator, mounted on the rear of the cabinet.The final signature Amphion characteristic is their use of auxiliary bass radiators for bass loading (the term ‘loading’ comes from the idea that you ‘load’ the bass driver diaphragm with the mass and compliance of the air in the cabinet). The ABR technique is closely related to ‘simple’ port tube reflex loading (ABR is in fact a form of reflex loading), but rather than employ a tuned port to extend the bass driver output, a driver diaphragm and suspension (with no motor system) is used.

To my way of thinking, there’s two primary advantages to the ABR technique over the simple reflex port. Firstly, the ABR tuning frequency can be adjusted simply by adding or removing mass to or from the diaphragm. This is in contrast to having to adjust the length of the port, which, in compact monitors, might not fit easily in the cabinet once it is of large enough diameter to provide adequate linear airflow. Secondly, ABRs are immune to the potentially audible undesired resonance effects that simple port tubes often suffer. That perhaps makes it seem as if anybody would be crazy to choose the simple reflex port option, but of course simple ports do have advantages; they’re inexpensive, simple (the clue is in the name) and consume much less cabinet panel real estate than ABRs, and with thoughtful design simple ports can be made to work perfectly well.

Gen X

And so to the modifications that have turned the One18 into the One 18X. The changes primarily concern the tweeter and crossover. Firstly, the tweeter is now the same as the device employed in the active high‑end One25A that I reviewed, very positively, back in SOS May 2024. The revised tweeter offers, say Amphion, significantly extended high‑frequency bandwidth, increased linear dome‑excursion capability and much lower distortion than the ‘old’ tweeter. Interestingly, Amphion’s founder, Anssi Hyvönen, says that part of the motivation behind developing the X tweeter is that the increasing prevalence of headphone listening and monitoring is raising listeners’ expectations of extended HF bandwidth and lower distortion — both of which are ‘easy’ to achieve with headphone drivers. Along with the new tweeter the One18 also features a revised waveguide profile.

Any change to a driver in a passive speaker is going to require some crossover revisions. In the One18X, those changes are firstly aimed at accommodating any baseline response shape or sensitivity characteristics that the new tweeter brings. And, while improved objective performance is the goal, it was important to Amphion that the subjective character not be too different from the existing One18. Otherwise, qualities that made the One18 so popular would be lost.

Measure Boogie

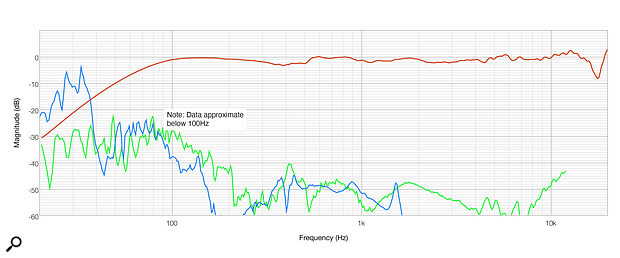

I took the One18X to my usual speaker measuring space and recorded some acoustic data that, hopefully, will illustrate some of the concepts I’ve been describing. Diagram 1 shows the One18X axial frequency response overlaid with second and third harmonic distortion curves (SPL was 90dB at 1m). While not the flattest axial frequency response I’ve ever measured, the One18X response is perfectly reasonable and generally falls within ±2dB limits between 100Hz and 10kHz. And, as I’ve written many times, there’s so much more to any speaker than any single frequency‑response curve. The One18X distortion performance is generally very good, but its high‑frequency third‑harmonic performance is notably excellent. It falls off the bottom of my graph and is typically better than 60dB below the fundamental, which makes it less than 0.1%. That’s not unheard of in speakers, but it’s not heard very often. Amphion’s claim that the new tweeter offers lower distortion looks to be realised.

Diagram 1: The One18X’s one‑axis frequency response (90dB SPL at 1m) is shown in red. The green and blue traces show second‑ and third‑harmonic products, respectively.

Diagram 1: The One18X’s one‑axis frequency response (90dB SPL at 1m) is shown in red. The green and blue traces show second‑ and third‑harmonic products, respectively.

Returning to the axial frequency response for a moment, the dip and recovery apparent above 15kHz is sometimes typical of waveguide tweeters. It’s caused by the inherent narrowing dispersion of the naked dome as frequency increases (the dome radiation ‘decouples’ from the waveguide). Some speaker engineers combat the effect by placing a high‑frequency dispersion‑modifying ‘phase plug’ in front of the dome, while some feel that this kind of technique risks introducing audible artefacts. I’m agnostic on the matter, and it’s a perfectly reasonable decision on Amphion’s part to leave the phenomenon unmodified — 15kHz and above is, after all, questionably significant for the majority of listeners.

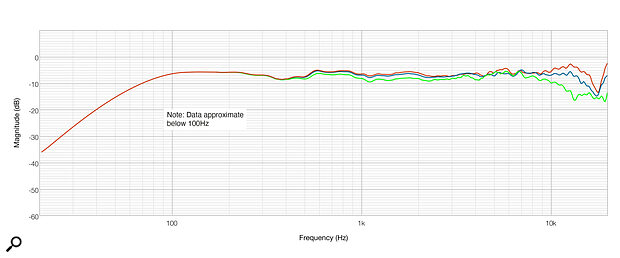

Diagram 2: Comparing the axial response (red) with measurements taken 20 and 40 degrees horizontally off‑axis (blue and green traces, respectively).

Diagram 2: Comparing the axial response (red) with measurements taken 20 and 40 degrees horizontally off‑axis (blue and green traces, respectively).

Diagrams 2 and 3 provide a perfect illustration of the midrange dispersion control that comes with the combination of a waveguide tweeter and a low crossover frequency. Diagram 2 shows the One18X axial frequency response overlaid with curves for 20 and 40 degrees horizontal dispersion. The off‑axis curves are extremely impressive in their uniformity and lack of any major discontinuities. This is especially the case through the midrange, where a conventional, non‑waveguide system would more typically show a significant off‑axis midrange dip followed by a recovery on the other side of the crossover region.

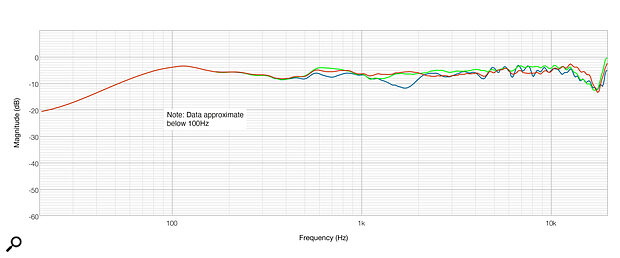

Diagram 3: Axial response (red) versus +15 and ‑15 degrees vertically off‑axis (green and blue traces, respectively).

Diagram 3: Axial response (red) versus +15 and ‑15 degrees vertically off‑axis (green and blue traces, respectively).

Diagram 3 shows the axial frequency response again, overlaid with curves for +15 and ‑15 degrees vertically off‑axis. While the ‑15 curve shows a small degree of phase cancellation in the crossover region, the +15 curve remains nicely linear through the crossover. The practical result of this curve is that the One18X is best heard either directly on axis or slightly above. If the monitors were installed on a relatively high monitor shelf, I’d consider turning them upside‑down.

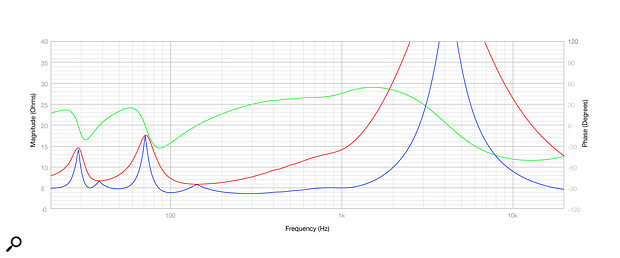

Diagram 4: The One18X’s input impedance. Red = magnitude; green = phase; blue = EDPR.

Diagram 4: The One18X’s input impedance. Red = magnitude; green = phase; blue = EDPR.

Finally, before I get to describing what I thought of the One18X subjectively, Diagram 4 shows its input impedance and, as with the vast majority of speaker impedance curves, it illustrates that amplifiers don’t have an easy time. I’ve overlaid a third curve to Diagram 4 in addition to the usual magnitude and phase curves. This Equivalent Peak Dissipation Resistance (EPDR for short) curve displays the effective resistive load the amplifier “sees” from the combination of magnitude and phase. The One18X EPDR curve drops to under 5Ω for a significant portion of the audio band, and while that’s relatively low, it’s not nearly as amp‑punishing as some EPDR curves I’ve seen. In the grand scheme of things, the One18X constitutes not too challenging an amplifier load. Earlier I quoted the One18X impedance spec of 8Ω. Is that fair? Well, traditionally (I believe it dates back to a 1970s German DIN specification), to qualify as an 8Ω speaker the impedance shouldn’t drop below 6.4Ω anywhere in the audio band. I think the One18X just about squeaks through — its minimum is just over 6Ω at 150Hz.

Amped Up

Firing up the One18X and loaned Amphion Amp700 power amplifier, and listening to a variety of reference tracks and in‑progress mixes, my first impressions were of a slightly bright high‑frequency balance combined with a very slightly warm midrange, almost as if the One18X has a faint smile shape to its tonal balance. But I was also struck by the way the One18X reveals immense quantities of detail in the midrange and lower‑HF bands: unintended noises‑off, edits and reverb tails that I’d never been quite so aware of before in material that I thought I knew well became more explicitly audible. Stereo imaging, too, was of a hugely high standard, with focus and depth presentation that extends beyond just the central phantom image.

Monitors have a noise floor, where all the various distortions and cabinet panel, driver or port resonances skulk around, and if the noise floor is low, then more programme detail becomes audible and stereo imaging becomes more solid. In those terms, the One18X undoubtedly has an extremely low noise floor, and that helps to make it a superb monitoring tool. To my way of thinking (and listening), a monitor’s noise floor is more important, within reason, than its tonal balance — not least because these days, with such easy access to monitoring EQ (via room optimisation or monitor control software), monitors can have pretty much any broad‑brush balance we like. And having said that, as the One18X’s raw tonal balance was marginally bright for my taste, I spent the rest of my listening with a 1dB shelving cut from 4kHz upwards implemented in my Audient ORIA interface control app.

With or without my tonal balance preference, in addition to offering immense detail in its presentation, the One18X tweeter handles sibilance really well, without a hint of harshness or sounding pushy. There’s no sense of, “Hey! Listen to me! I do detail!”, just an accurate and fully realised version of what’s present in the programme material. I think there are two phenomena at play here. Firstly, the well‑managed mid and high‑frequency dispersion of the One18X system means there’s no wild swings of tonal signature between direct and reflected sound reaching the ears; and secondly, the incredibly low distortion generated by Amphion’s new tweeter, especially in the third harmonic, means it’s adding almost nothing objectionable of its own.

It’s the kind of monitor that doesn’t leave you second guessing...

I’ve always admired the ABR‑based balance Amphion have developed between the temporal accuracy of closed‑box bass loading and the bandwidth and power‑handling advantages of reflex loading. The impedance curve of the One18X actually reveals that its low‑frequency alignment is relatively well damped, and in electro‑acoustic terms, I see it living somewhere between closed‑box and reflex; successfully expressing some of the characteristics of both techniques. And that’s just how One18X bass sounds. Its bandwidth is nicely extended, so it can play some very low bass, but that bandwidth extension isn’t achieved at the expense of time or pitch accuracy. It’s the kind of monitor that doesn’t leave you second guessing what’s going on between that kick drum and bass guitar. Again, that makes the One18X a really effective mix tool.

To wrap up, I’m really pretty certain that the One18X is an improvement on the One18, and my feeling is that it’s not a small improvement either. Both my measurements and listening suggest that Amphion’s new tweeter is a genuine advance, and its effect lifts the One18X performance to a new level. The One18X is one of those review monitors that I was sad to see packed up and waiting for collection.

Alternatives

Considering an approximate package price including an Amphion Amp700 power amp, active monitors worth considering in the same kind of ballpark could include products such as the ATC SCM20A, Mesanovic CDM65, PMC6, PSI Audio A21M and Genelec 8341.

Pros

- Remarkable level of midrange and tweeter detail.

- Fabulous, low‑distortion high frequencies.

- Pin‑sharp stereo imaging focus.

- Very well judged bass.

Cons

- None.

Summary

The Amphion One18 always was a very capable nearfield monitor. It’s significantly better now and hugely impressive.

Information

£3300 / €3750 per pair including VAT.

Amphion Loudspeakers Ltd +358 17 2882 100.

$4100 per pair.

When you purchase via links on our site, SOS may earn an affiliate commission. More info...