Can GForce capture the character of the legendary Oberheim 8‑Voice in software?

Back in 2003, the GForce Oddity was the first ‘modelled’ soft synth I reviewed. In addition to a sound that was closer to the original ARP than I had expected, things such as the ability to run multiple instances, velocity and aftertouch sensitivity, MIDI automation and, of course, the lack of crackly faders, meant that I was impressed. The following year, the ImpOSCar arrived, followed by the Minimonsta before GForce turned their attention toward the Oberheim SEM and its polyphonic progeny, the FVS 4‑Voice and EVS 8‑Voice. But this was when fate intervened because, during development, Tom Oberheim re‑released the SEM in hardware form. So the chaps at GForce transferred their attention to other projects, which left the field clear for Arturia to release SEM V. This included a system by which you could apply offsets to a user‑defined selection of parameters, thus imitating some of the flexibility of the originals but, while this introduced a degree of poly‑timbrality, it wasn’t the same as a colony of independent SEMs. Then, three years ago, Tom Oberheim discontinued production of his SEMs, so GForce decided to resurrect their project and develop a truer emulation of the 8‑Voice.

Here are some demo sounds from GForce:

The Virtual SEMs

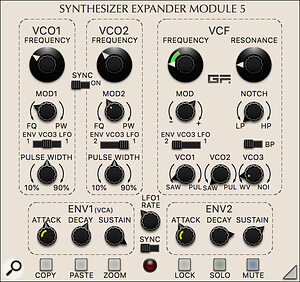

I don’t propose to describe the sound generation capabilities of the SEM here because there’s a wide range of resources elsewhere if you want to pursue this further. But the differences that lie between an original SEM and the virtual SEMs in the OB‑E are important. For example, the EXT (external signal) modulation option in each of VCO1, VCO2 and the VCF has been replaced with a VCO3 option, which tells us that there’s a third oscillator per voice lurking somewhere. Likewise, a VCO3 Wave/Noise knob has replaced the Ext#1/Ext#2 knob in the mixer. In the filter section, the mode knob of the original has been replaced by the LP/BR/HP knob and BP switch of the 21st‑century SEM reissues, and an LFO Sync switch has replaced the VCA On/Ext switch. Underneath these, there are now eight additional items in each SEM. If you’ve ever tried to program an 8‑Voice you’re going to love the first two of these because they allow you to Copy the settings in any given SEM and Paste them into any other. Next to these, Zoom allows you to see and edit the front and rear of any given SEM simultaneously, while Lock, Solo and Mute do as you would expect. There’s also a red lamp that lights up when an SEM is in use, and a triangular button at the bottom right that switches between its front and rear panels.

The rear panel introduces all manner of new facilities: an extra VCO, more extensive controls for the main LFO, filter tracking and sophisticated performance capabilities.There are five sections on the rear panel, none of which existed on the original SEM. Starting with the detailed controls for LFO1, this now offers six waveforms, an amplitude ramp (called Intro) and a key retriggering option. But if this is called LFO1, where are the implied LFO2, LFO3... and so on? The answer lies in part in VCO3, which adds noise and a sine wave to the waveforms offered on the front panel, but loses the variable pulse wave in favour of a fixed square wave. It can perform as either an audio frequency oscillator or as an additional LFO and, in either range, it offers two outputs; one directed to the mixer, and the other to the modulation inputs of VCO1, VCO2 and the VCF. These don’t have to carry the same signal, so you can use its pink noise generator as an audio signal and one of the cyclic waveforms as a modulator, and vice‑versa. Since you can sweep the frequency of VCO3 using ENV1 or ENV2, some interesting modulation and FM effects can be obtained. Key triggering and sync of the LFO mode are provided, as is Delay, which is another ramp from zero to full amplitude.

The rear panel introduces all manner of new facilities: an extra VCO, more extensive controls for the main LFO, filter tracking and sophisticated performance capabilities.There are five sections on the rear panel, none of which existed on the original SEM. Starting with the detailed controls for LFO1, this now offers six waveforms, an amplitude ramp (called Intro) and a key retriggering option. But if this is called LFO1, where are the implied LFO2, LFO3... and so on? The answer lies in part in VCO3, which adds noise and a sine wave to the waveforms offered on the front panel, but loses the variable pulse wave in favour of a fixed square wave. It can perform as either an audio frequency oscillator or as an additional LFO and, in either range, it offers two outputs; one directed to the mixer, and the other to the modulation inputs of VCO1, VCO2 and the VCF. These don’t have to carry the same signal, so you can use its pink noise generator as an audio signal and one of the cyclic waveforms as a modulator, and vice‑versa. Since you can sweep the frequency of VCO3 using ENV1 or ENV2, some interesting modulation and FM effects can be obtained. Key triggering and sync of the LFO mode are provided, as is Delay, which is another ramp from zero to full amplitude.

Filter tracking is another new feature, but a much larger section deals with MIDI velocity; with no fewer than 11 knobs controlling 16 destinations this places a huge degree of control under your fingers. Finally, there are five bipolar destinations for aftertouch. You can step through the destinations and programme the amount of modulation for each, whereupon all five (brightness, loudness, modulation rate, and the VCO1 and VCO2 pitch/PW modulation amounts) can be controlled simultaneously.

Two new buttons are also found on the rear panel: Load (or SEM Load when zoomed) and Save (or SEM Save when zoomed). These allow you to save and recall the parameters of an individual SEM rather than the whole instrument. If you wish, you can also load a saved SEM sound into all eight when recalling it.

Soft synths have improved hugely in recent years, and this one is right at the top of the pile.

Making The SEMs Work For You

A small range of additional modules was available for the 8‑Voice, and the three most important of these were the Polyphonic Synthesizer Programmer, the Output Module and the Polyphonic Keyboard (which, despite its name, was a module). There’s no need for the first of these in OB‑E because, with the exception of the global VCO tuners, all of its functions are contained within the virtual SEMs themselves. In contrast, the Output Modules are recreated faithfully, with the Levels, Pans and a Master Level for each row of SEMs. Each also offers three buttons to lock the row from edits, solo it, and mute it.

Although the front panels of the OB‑E’s virtual SEMs look strikingly like an original hardware SEM, there are many upgrades that drag it firmly into the 21st century.With the exception of the global VCF cutoff frequency knob (which has gone AWOL) the functions provided by the Polyphonic Keyboard module are distributed between the panel to the left of the OB‑E’s virtual keyboard (Mode, Portamento and Tune) and in a group of four Keyboard switches above it. The key assignments offered are Poly, Mono (SEM1 with multi‑triggering) and Legato (SEM1 with single‑triggering). Two voice assignment modes are also offered: if Reset is selected, SEM1 will always be the first to play when a new note or chord is played. Selecting Cont (continuous) means that the next available SEM will be used. Split separates the upper and lower rows, allowing you to play these as two groups of four SEMs either side of a user‑defined split point, but the switch that allowed you to allocate the number of SEMs in each row that are played on either side of the split has gone. Apparently, GForce is looking into this as a possible upgrade. Unison does as promised, layering either all eight SEMs, or the two rows of four when in Split mode, and you can use the Detune knob to imitate the vagaries of analogue tuning and create the usual range of thickening effects. Unfortunately, you can’t have a Unison patch on one side of the split and not on the other, so unison basses below chords, or unison leads above them, are not possible.

Although the front panels of the OB‑E’s virtual SEMs look strikingly like an original hardware SEM, there are many upgrades that drag it firmly into the 21st century.With the exception of the global VCF cutoff frequency knob (which has gone AWOL) the functions provided by the Polyphonic Keyboard module are distributed between the panel to the left of the OB‑E’s virtual keyboard (Mode, Portamento and Tune) and in a group of four Keyboard switches above it. The key assignments offered are Poly, Mono (SEM1 with multi‑triggering) and Legato (SEM1 with single‑triggering). Two voice assignment modes are also offered: if Reset is selected, SEM1 will always be the first to play when a new note or chord is played. Selecting Cont (continuous) means that the next available SEM will be used. Split separates the upper and lower rows, allowing you to play these as two groups of four SEMs either side of a user‑defined split point, but the switch that allowed you to allocate the number of SEMs in each row that are played on either side of the split has gone. Apparently, GForce is looking into this as a possible upgrade. Unison does as promised, layering either all eight SEMs, or the two rows of four when in Split mode, and you can use the Detune knob to imitate the vagaries of analogue tuning and create the usual range of thickening effects. Unfortunately, you can’t have a Unison patch on one side of the split and not on the other, so unison basses below chords, or unison leads above them, are not possible.

The panel offers a dedicated vibrato LFO that you can direct to the upper row, the lower row or both, and the manual promises a pitch‑bend knob, although this was removed between prototyping and release. There are also five additional programming buttons. Undo and Redo allow you to step backward and forward through your edits, which is great when you’ve ruined a patch that was progressing nicely and would like to pick up from the point before you did so. Next to these, Flip does what it implies, flipping all eight SEMs from their front to rear panels and back again, while Group and Offset allow you to edit all unlocked SEMs simultaneously from any of them that you choose, either as absolute values (Group) or, with a few logical exceptions, as relative changes (Offset). This is a whole new world for 8‑Voice programmers!

Press the SEQ/FX button to switch between the virtual keyboard and two panels showing the sequencer and delay effect.

Press the SEQ/FX button to switch between the virtual keyboard and two panels showing the sequencer and delay effect.

Behind the virtual keyboard you’ll find a single line display and 15 additional buttons. The first of the buttons takes you to a MIDI CC ‘learn’ mode that provides access to almost every control, including many of the switches. Unlike many other soft synths, you can assign a single CC to multiple parameters within a given SEM and even to different parameters in different SEMs and this offers a rare and welcome degree of flexibility. However, there’s no way to save and recall MIDI setups for different controllers or environments. When in CC mode, the otherwise hidden Clear button becomes visible. This clears every assignment, so use it with care.

The next 10 buttons provide patch handling. The purposes of Load and Save are obvious, but those of Mono and Poly are not. The first of these turns the OB‑E into a ‘1‑Voice’, displaying the front and rear of a single SEM and loading a set of default parameters as a starting point for editing. In Poly mode, the eight SEMs are Grouped, all eight are displayed, and a different set of parameters — suitable for use as a starting point for polyphonic patches — is loaded. Next to these, buttons M1 to M4 are memories for any four patches that you may need at the touch of a button, while the Prev and Next buttons step through the patches in the selected folder (see the ‘Patch Management’ box). Beneath these, the Sequencer button only switches the sequencer on and off; to access it you have to press the triangular Seq/FX button to the far right of the GUI. Similarly, the Delay button switches the solitary effect on and off. You can assign MIDI CCs to both of these, which is again useful.

In Use

Like the original FVS and EVS, you can set up each SEM to generate the same sound, thus making the OB‑E a conventional 8‑voice polysynth. But while this can sound fab, the SEMs don’t have to produce the same sound unless you want them to. You can let your imagination run wild, creating different sounds on each to create huge polyphonic ensembles or either four or eight different timbres under a single key. You can then use the Level and Pan knobs to balance each of the sounds and to spread them across the soundstage. And don’t forget split mode, which allows you to play two unrelated sounds either side of the split. Indeed, if you use the sequencer in SEM8 mode (see box) you can have three zones of sound generation, just as on the original: one SEM for the sequence, three in the Upper split, and four in the Lower.

But does it sound like an 8‑Voice? Answering this is fraught with disclaimers about the vagaries of SEMs and I would have to ask, ‘which 8‑Voice?’. Nonetheless, I was able to reach a number of conclusions by running the OB‑E alongside a 21st‑century SEM as well as half of my sometimes badly behaved and always unwieldy 8‑Voice.

When I first tested it a couple of months before its release I found that the OB‑E’s oscillators were static and a bit lifeless, so I reported this to GForce. They discovered that the drift algorithm had been disabled during debugging, so they fixed this and sent me a revised copy. What a difference that made! Now, the underlying tones of the three synths are all but identical, although the ranges over which the pulse widths can be swept differ slightly on all of them. Elsewhere, the filter appears to open further and the amplitude of its resonance is greater on the modern SEM, to the extent that it will self‑oscillate quietly, whereas the vintage SEMs and the soft synth will not. But these differences tend only to reveal themselves in a forensic comparison; by and large, slight tweaks can achieve almost identical sounds. Greater differences were revealed when I invoked oscillator sync. The maximum sweep of the modern SEM is greater than that of the OB‑E, so you can obtain a greater degree of ‘tear’. The OB‑E’s response is again closer to that of the vintage SEMs.

Zoom mode allows you to see the front and rear panels of a given SEM simultaneously, making it much easier to work out what’s going on and speeding up programming considerably.

Zoom mode allows you to see the front and rear panels of a given SEM simultaneously, making it much easier to work out what’s going on and speeding up programming considerably.

The next stage was to create some polyphonic patches on the 8‑Voice and the OB‑E. As I discovered many decades ago, the variations between the SEMs in an 8‑Voice can be much larger than you expect, and it’s this as much as anything else that makes it sound as it does. So I programmed appropriate differences in tuning, filter cutoff frequencies, LFO rates and contour responses within the OB‑E, whereupon it soon started to assume the character of the original.

Next, I abandoned the constraints of the original SEM architecture and explored the facilities offered by VCO3, the additional capabilities of LFO1, the vibrato LFO, and filter tracking. The underlying Oberheim‑iness remained but, for obvious reasons, the range of sounds I could obtain increased hugely, rendering direct comparison with the original meaningless. It was also time to add velocity, aftertouch, poly‑aftertouch and MPE into the equation. Oh wow! If you get the chance, try the ‘Homage To Lyle Split’ patch from the factory sounds — for me, it’s everything that the 8‑Voice was about, and it’s gorgeous. With just a smidgen of velocity and pressure sensitivity, it takes the OB‑E even further than before while retaining the character of the underlying SEMs.

So, having given the OB‑E a glowing write‑up, is there anything that I would consider changing? Of course there is. For example, I like it when a synth’s contour speeds can track the note number because this makes it more like an acoustic instrument. But I realise that this is not what the 8‑Voice was designed for, so I’ll say no more about it. I might also have considered adding the mixer inputs to the list of destinations for VCO3 because, as it stands, AM sounds are not possible. It’s also worth noting that, unlike many soft synths, the OB‑E has no modulation matrix. However, this makes sense; a matrix can be brilliant when you have one set of parameters for all the voices, but it’s less appropriate for a colony of monosynths. Regarding the user interface, I came to like this very much. Sure, I occasionally encountered a tiny ‘fluttering’ of some of the graphic elements, but this had no effect on the sound and was too minor to be an annoyance. In fact, the only thing that I might suggest changing here would be the means by which the effects of velocity and pressure sensitivity are displayed. When you assign velocity to a parameter a yellow line appears within its knob to display the direction and extent of the change that can take place. Similarly, the direction and extent of any change caused by aftertouch is shown using a blue line. Any overlapping effects of velocity and aftertouch are shown in green, which makes sense but, for clarity, I would have argued for two, non‑overlapping lines. Having said that, I suspect that this might have been tricky to implement on low GUI sizes so, again, I’ll say no more.

Conclusions

With the OB‑E, you can now play something that looks and sounds much like an 8‑Voice, but without the inconvenience, back pain and servicing costs. Conventional patches can sound fantastic and, if they’re too well behaved for your tastes, you can make them sound as old and decrepit as you wish. Its additional facilities have been chosen to retain the character of the original while extending its capabilities, and the addition of velocity‑ and pressure‑sensitivity take it where no 8‑Voice has ever gone before. Does it always sound identical with any given example of the original synth? Probably not. Is that relevant? Probably not. Soft synths have improved hugely in recent years, and this one is right at the top of the pile. I have to admit that I’m impressed.

Patch Management

The keyboard mode and patch management controls lie directly above the keyboard, together with automatable on/off switches for the sequencer and delay, plus access to MIDI Learn, the sequencer and the delay.

The keyboard mode and patch management controls lie directly above the keyboard, together with automatable on/off switches for the sequencer and delay, plus access to MIDI Learn, the sequencer and the delay.

The OB‑E doesn’t have a conventional patch management system or librarian. Instead, clicking on the Save button above the keyboard takes you to a hidden folder [User/Library/Audio/Presets/GForce/OB‑E] within which you can create your own folders and into which you can place your own sounds. It’s an odd way of doing things, but it’s necessary because, while there are 65 Tags for the factory sounds hidden in HD/Library/Audio/Presets/GForce/OB‑E, you can’t allocate these within your own, so your only recourse is to create suitably named folders and place appropriate patches in each. The same system with different paths is employed for SEM factory sounds, your own SEM patches, and Sequencer presets.

One of the factory folders is special; if you place a patch in here and give it a name starting with a number, that’s the patch that will be loaded when the appropriate MIDI Program Change is received. If you want to move things between folders, you can load and resave them, but a quicker way is to access the hidden folders in the usual Mac OS fashion and move or copy the files in the usual fashion. Another small complication is that, when using OB‑E’s standalone version, your patches are saved in Logic’s .aupresets format so, if you want to make sure that they’re compatible when using other hosts, you may need to edit and save them within the DAW itself.

Clicking on Load reveals a window offering three options — Factory, User and Tags — the first two of which takes you to the appropriate hidden folders, and the actions of all of which should be self‑explanatory.

The Sequencer

Based in part upon the Oberheim MS‑1, the OB‑E’s eight‑step sequencer is both a sequencer and an arpeggiator, and it offers far more features and delivers far greater flexibility that you might imagine.

Based in part upon the Oberheim MS‑1, the OB‑E’s eight‑step sequencer is both a sequencer and an arpeggiator, and it offers far more features and delivers far greater flexibility that you might imagine.

The OB‑E’s (up to) eight‑step sequencer is based upon the original Oberheim MS‑1, but with numerous enhancements. You can program the Note, Gate time and Velocity of each step, as well as the rate and swing of the sequence. When used as a plug‑in, the tempo is determined by the host; when used standalone, you set the underlying tempo in the synth’s preferences, which means that the rate is always displayed as a clock division. There are 15 preset gate/velocity/swing templates available.

Note values are always quantised, but you can force any sequence into any of the 12 major scales or 36 minor scales. Creating sequences in one scale and replaying them in others can generate interesting results but, unfortunately, this is one of the few parameters that can’t be controlled using a MIDI CC. I asked GForce whether CC control might be added at a later date and, while promising nothing, they’re looking into it.

There are five playback modes — forward, backward, forward/backward, random and chord — and you can define which is the first step played when the sequence is started (which can be interesting when swing is applied), and choose which SEM is the first to be used (which can create fascinating variations when the SEMs are programmed differently).

You can transpose a sequence by sending it MIDI Notes, and selecting Hold causes the sequencer to stop when a Note Off is received and start again at the appropriate transposition when the next Note On is received. You can modify steps during playback and you can even change the sounds while a sequence is running.

Despite all of this sophistication, you can also recreate the original 8‑Voice mode of operation in which only SEM8 is sequenced, allowing you to play SEMs 1‑7 in conventional fashion. But something that I haven’t seen mentioned is the sequencer’s ability to perform as an arpeggiator. You achieve this by selecting All/Auto mode and choosing the mode and the number of octaves over which you wish it to play, whereupon the length of the sequence is determined by the number of notes that you press at any given time and the note values are inserted into the appropriate steps. In other words, an arpeggiator.

While investigating all of this, I found two bugs in the sequencer, but they seem to be specific to my test system. Firstly, if you click and hold on the MIDI button, the sequence is turned into a MIDI file that you can drag and drop into the DAW of your choice. However, this doesn’t currently work with Digital Performer. Secondly, the pop‑up menu for the scales doesn’t appear on my system. I have reported both of these, and GForce already think that they’ve identified the causes. With any luck, they will be fixed by the time that you read this.

The Delay effect

The OB‑E eschews a sophisticated multi‑effects section in favour of a conventional ‘ping‑pong’ stereo delay that, thanks to its LFO, is also capable of generating a range of modulation effects.

The OB‑E eschews a sophisticated multi‑effects section in favour of a conventional ‘ping‑pong’ stereo delay that, thanks to its LFO, is also capable of generating a range of modulation effects.

Unlike the many soft synths that boast sophisticated multi‑effects sections, there’s just a stereo delay at the end of the OB‑E’s signal path. Delay times range from 10ms to 10 seconds, or from 1/32 beat to 4 beats when sync’ed to MIDI Clock, and there’s a dedicated LFO so that you can create a selection of modulation effects.

You can apply the delay to the Lower row of SEMs, the Upper row, or both, as you choose. A delay is of massive benefit to OB‑E sounds, but an 8‑Voice sounds wonderful with a bit of overdrive so it would have been nice to have access to this as well as simultaneous chorus and delay/reverb effects. On the other hand, many people bypass the effects units within soft synths in favour of their favourite plug‑ins. You pays yer money...

A Very Short History Of The SEM

The Oberheim SEM (Synthesizer Expansion Module) wasn’t developed as an instrument in its own right, but rather as an addition to an existing synth or sequencer. Following its release in 1974, Oberheim combined four of them in a case containing a keyboard and a voice allocation controller, and the FVS 4‑Voice was born. This was then followed by the various versions of the EVS 8‑Voice. Laborious to program and impractical to keep in tune, these could nonetheless sound glorious and are viewed as among the most desirable synthesizers ever released. They were superseded in 1979 by the OB‑X and, more recently, by the DSI/Oberheim OB6, which retains the concept of an individual SEM per voice.

No PC Version?

There’s currently no Windows version of the OB‑E, which has caused some consternation among the chattering classes. GForce has explained this in a statement on their website concluding, “we want to allay fears that just because OB‑E is Mac-only at present, it doesn’t mean we’re dropping PC”. I think it’s safe to expect a PC version at some point but I have no idea how long this might take, because GForce have stated that they’re more concerned with getting things done right than getting things done quickly. I approve.

Here's an overview video from Alex Ball to let you hear some of the OB-E's fabulous sounds:

Pros

- It really does feel like eight well‑behaved SEMs.

- It can sound remarkably similar to the unobtainium on which it’s based.

- It goes far beyond what was possible with an 8‑Voice.

- Polyphonic aftertouch and MPE compatibility make it a superb performance instrument.

- You can transport it and recall your sounds in full without having to spend an hour tuning it.

- I didn’t experience a single crash or glitch during the review.

Cons

- It’s only available for the Mac.

- You can’t save and recall MIDI maps.

- You can’t have unison on one side of a split and not the other.

- The effects section is limited by modern standards.

- The patch management system needs development.

Summary

There’s something a bit special about SEM‑based polysynths, and the OB‑E captures this and then adds more. You’re not going to find an affordable 8‑Voice, so test this instead; you may be surprised.