Detroit microphone maker Deni Mesanovic applies his considerable knowledge of transducers to produce an impressive debut studio speaker.

My colleague Bob Thomas reviewed the Mesanovic Model 2 ribbon microphone back in SOS February 2016 and was extremely impressed with what he found. The second appearance for Mesanovic in this magazine is not a new microphone, however, but a high‑end, active nearfield/midfield monitor, the RTM10. So what, you might ask, is a ribbon‑mic specialist company doing manufacturing a monitor? It’s actually not quite as leftfield as it might appear because there are significant similarities between the design, engineering and manufacturing of ribbon microphones and ribbon tweeters. I’ll expand on that a little further down the page.

First, a little about the company. Based in Detroit, Mesanovic were founded by Deni Mesanovic, who had built a ribbon mic as part of his degree in Sound Engineering at the University of Michigan. That experience led him to become involved in mic manufacture on a commercial basis, initially ribbon mics and latterly a condenser model. Mesanovic are unashamedly an artisan‑style organisation, making products in low numbers and retaining as much manufacture in‑house as possible. As you might already suspect from the pictures, the RTM10 aspires to very high performance and is not an inexpensive monitor. It’s aimed at serious, professional users with a need for, and resources to invest in, high‑end studio hardware.

Physical Attributes

As nearfield monitors go the RTM10, with its single side‑mounted bass driver, is at first sight a somewhat quirky one, but there’s a good deal of thoughtful and astute electroacoustic engineering going on behind its quirks. In terms of the basic formula it’s a three‑way monitor comprising a nominally 250mm (10‑inch) bass driver, a 130mm (5‑inch) midrange driver and a 130 x 9.3 mm ribbon tweeter. The internal amplification is all Class‑D NCore from Dutch specialist Hypex. It’s rated at 250 Watts for the bass and midrange drivers and 100 Watts for the tweeter. The crossover frequencies are at 150Hz from bass driver to midrange driver, and at 3.5kHz from midrange driver to tweeter, all with steep, fourth‑order (24dB/octave) filter slopes. The band between the two crossovers (150Hz to 3.5kHz) is unusually wide and gives the midrange driver around four and a half really important octaves to cover. I’ll cover the reasons behind giving all that responsibility to the midrange driver further down the page.

The RTM10’s single LF driver is mounted in the side of the speaker’s cabinet. Rear‑panel controls are limited to 0, 2 and 4 dB bass cut options, to compensate for placement near boundaries.The RTM cabinet is narrow, but relatively tall and decidedly deep so it makes some significant demands on mounting real‑estate. Each cabinet also of course needs a good distance of free air to the side on which the bass driver is located. Mesanovic suggest that the monitors should be installed with the bass drivers located inwards, however there is no specific acoustic argument for this arrangement. The bass drivers radiate omnidirectionally to significantly above their crossover frequency so there ought to be no significant performance difference between inwards or outwards location.

The RTM10’s single LF driver is mounted in the side of the speaker’s cabinet. Rear‑panel controls are limited to 0, 2 and 4 dB bass cut options, to compensate for placement near boundaries.The RTM cabinet is narrow, but relatively tall and decidedly deep so it makes some significant demands on mounting real‑estate. Each cabinet also of course needs a good distance of free air to the side on which the bass driver is located. Mesanovic suggest that the monitors should be installed with the bass drivers located inwards, however there is no specific acoustic argument for this arrangement. The bass drivers radiate omnidirectionally to significantly above their crossover frequency so there ought to be no significant performance difference between inwards or outwards location.

The RTM10 cabinets are constructed from 25mm MDF panels with strategically located bracing. The vertical front edges of the cabinet carry a generous radius that will reduce high‑frequency edge diffraction effects. A charcoal‑coloured textured paint finishes things off. The combination of thick MDF panels and, I suspect, a particularly heavy bass driver magnet, results in the RTM10 not falling into the ‘lightweight’ category. They’re a not insignificant 25kg each. Mind your back, and whatever you chose to stand the RTM10 on. I used a pair of heavy‑weight mass‑loaded speaker stands, but Mesanovic do make their own vibration‑isolating stand, called the Iso Platform (pictured).

Around the back of the RTM10 cabinet sits the traditional connection and heatsink panel. Balanced XLR and unbalanced phono sockets are fitted. Despite the monitor’s digital internal signal path, its inputs are analogue only. The internal DSP runs at 93.75kHz and features AKM Velvet Sound DAC and ADC components. As with the Ex Machina Pulsar we reviewed in the March 2021 issue, the RTM10 offers no input sensitivity adjustment. I wonder if this is the beginning of a trend? The lack of input sensitivity adjustment is I think in practice of little significance. I can’t remember the last monitor I reviewed where I felt the need to adjust the sensitivity and, ultimately, it’s probably better not to offer sensitivity adjustment than implement it unsatisfactorily (which happens rather too often). The final feature of interest on the rear panel is a small push button that offers three low‑frequency EQ options: ‘flat’, ‑2dB and ‑4dB, the cuts providing some compensation for room boundary gains.

Middle Ground

Back onto the midrange driver, it’s a unit manufactured by SB Acoustics in Indonesia and features a geometrically reinforced aluminium diaphragm driven by a 30mm‑diameter, copper‑clad, aluminium‑wire voice coil. SB Acoustics are an interesting organisation that have found significant commercial success in the last decade or so through marrying Danish driver design expertise with cost‑effective Indonesian manufacturing. SB Acoustics drivers are typically of very high quality and performance. As dedicated midrange drivers go, the RTM10 unit has relatively generous maximum linear diaphragm movement (±5mm), and this ties into Mesanovic’s decision to locate its bass driver on the side of the cabinet.

A side location for a bass driver brings one really big advantage — packaging. It means a larger‑diameter driver can be employed, which brings reduced LF distortion, high volume level capability and extended LF bandwidth, while at the same time enabling a narrow frontal width dimension, which looks attractive and helps with wider horizontal dispersion. But the side bass driver location also means that the crossover frequency to the midrange driver needs to be relatively low so that the bass driver avoids radiating any midrange energy asymmetrically sideways — which would potentially result in all sorts of tonal balance, imaging and room integration issues. And a low crossover frequency also asks more of the midrange driver in terms of diaphragm displacement and thermal power handling.

One last diversion on the side‑mounted bass driver before I move on to the RTM10 tweeter. A potentially interesting opportunity of side‑mounted bass drivers is to use two smaller drivers, one on each side. Doing so potentially brings a couple of further advantages. Firstly, working in mechanical opposition means the bass drivers input minimal mechanical energy into the cabinet carcass. Secondly, manufacture and shipping logistics doesn’t have to deal with “sided” pairs of speakers. I asked Deni Mesanovic why the RTM10 doesn’t take advantage of using twin drivers and, while acknowledging the potential advantages, he said that development work had shown that a single larger driver offered better low‑frequency bandwidth and distortion performance than was possible with two drivers, while still meeting manufacturing cost targets. There’s also an installation advantage to be had when only one side of the monitor needs to be kept free of obstruction. Monitors with bass drivers mounted on both sides are inherently more demanding of installation.

The RTM10 bass driver appears to be a relatively conventional aluminium diaphragm unit that clearly, from its oversized roll surround and impressive ±13mm linear displacement, is designed specifically for low‑frequency duties. Beneath the surface, however, the driver incorporates some sophisticated components and techniques within the magnet system aimed at reducing distortion. The driver is effectively a subwoofer unit, and, in fact, Mesanovic describes the low‑frequency element of the RTM10 as such. The bass driver is loaded by a closed‑box cabinet I’d estimate at just over 20 litres internal volume. The resulting low‑frequency bandwidth, massaged with some modest active EQ, is claimed to extend down to 28Hz (‑3dB) with a 12dB/octave roll‑off, as is to be expected with a closed‑box system.

The High End

And so to the Mesanovic ribbon tweeter. Firstly, the RTM10 tweeter is not a Heil/AMT‑style device with conductors embossed or embedded in a concertina‑folded diaphragm, but a ‘pure’ ribbon unit with a predominantly flat diaphragm that also acts as the electrical conductor. While all ribbon tweeters, in fundamental transducer terms, employ the same mechanism as moving‑coil drive units (an electrical conductor moving in a static magnetic field), pure ribbon tweeters are significantly different in that the component directly driven by the electromagnetic effect is also the acoustic diaphragm. This is exactly the same difference between a dynamic microphone and a ribbon microphone. If I were to describe the construction of a ribbon mic as a thin, lightweight conductive ribbon diaphragm suspended between the poles of a magnet, I could use exactly the same terminology for a pure ribbon tweeter. The major difference between the two devices is one of scale. For example, the diaphragm of the Mesanovic Model 2 ribbon mic is 50 x 5.8 mm wide while the diaphragm on the RTM10 ribbon tweeter is 75 x 9.3 mm wide. Ribbon tweeters need significantly greater radiating area than ribbon mics need acoustic sensing area.

Unlike the more common AMT tweeter, the ‘pure ribbon’ motor in the RTM10 uses a nominally flat ribbon; the diagonal corrugation reduces distortion at the lower end of its frequency range.The great advantage of ribbon tweeters over more conventional drivers is that the diaphragm is driven equally over its entire surface area, so its electroacoustic performance is not so dependent on the diaphragm’s mechanical characteristics. This means the diaphragm can be made extremely light. In the case of the RMT10 unit, the ribbon is made from a piece of laser‑cut aluminium foil that’s 4 microns (0.004mm) thick and weighs 0.01 grams. To put that into some perspective, a typical 25mm dome tweeter moving mass will weigh‑in at between 0.3 grams and 0.4 grams. That’s well over an order of magnitude heavier.

Unlike the more common AMT tweeter, the ‘pure ribbon’ motor in the RTM10 uses a nominally flat ribbon; the diagonal corrugation reduces distortion at the lower end of its frequency range.The great advantage of ribbon tweeters over more conventional drivers is that the diaphragm is driven equally over its entire surface area, so its electroacoustic performance is not so dependent on the diaphragm’s mechanical characteristics. This means the diaphragm can be made extremely light. In the case of the RMT10 unit, the ribbon is made from a piece of laser‑cut aluminium foil that’s 4 microns (0.004mm) thick and weighs 0.01 grams. To put that into some perspective, a typical 25mm dome tweeter moving mass will weigh‑in at between 0.3 grams and 0.4 grams. That’s well over an order of magnitude heavier.

The RTM10 ribbon element is not just thin and light. It’s subtly corrugated diagonally as Menasovic found this to help significantly with distortion at lower frequencies, and that brings me neatly back to the subject of crossover frequencies and the fact that the RTM10 midrange driver is employed up to a relatively high 3.5kHz. The reason for this is that a potential disadvantage of ribbon tweeters is that they tend not to be at their best towards the lower end of their band. Distortion tends to rise and power handling is limited simply because the ribbon is required to move too far. And while we’re on the subject of disadvantages, one that’s often considered the elephant in the room for ribbon tweeters is that high‑frequency dispersion on the vertical axis is significantly restricted. This however is not always as big a problem as it might appear — in particular for monitors that are heard in the nearfield with relatively stable primary listening positions. There’s also an argument that restricted vertical dispersion drives the listening room in a more benign manner by reducing ceiling and desk reflections.

There’s actually a second elephant in the ribbon tweeter room. The electrical impedance of a short piece of thin aluminium foil is inherently very low; far lower in fact than can be feasibly driven by a conventional audio amplifier. So in exactly the same manner that ribbon mics require an impedance‑matching transformer, so do ribbon tweeters. Mesanovic’s know‑how in designing and manufacturing high‑performance transformers for ribbon mics puts them in a great position to handle this element of ribbon tweeter technology, and in fact, the tweeter transformer employs the same toroidal core used in Mesanovic’s ribbon mic transformers.

Measure Novic

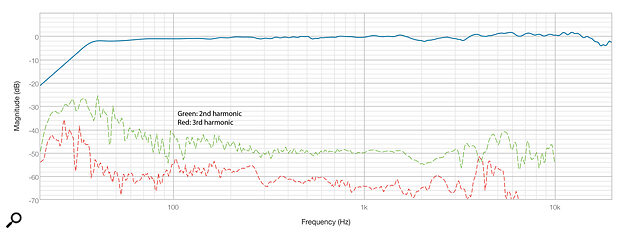

Diagram 1: The RTM10’s axial frequency response (blue trace) and measured second‑order and third‑order harmonic distortion (green and red dotted traces, respectively).

Diagram 1: The RTM10’s axial frequency response (blue trace) and measured second‑order and third‑order harmonic distortion (green and red dotted traces, respectively).

As is traditional I fired up FuzzMeasure in order to investigate a few of the matters I’ve described. Diagram 1 shows the axial frequency response of the RTM10 together with second‑ and third‑harmonic distortion, taken with a volume level of around 90dB at 1m. Both the frequency response and distortion results are impressive. The response is easily flat to within ±1.5dB all the way from about 50Hz to 12kHz, and the distortion levels are very well controlled. The low level of third‑harmonic distortion is especially notable. As I’ve no doubt opined before, while a flat frequency response isn’t everything, it does point to a well‑engineered monitor. Before I leave Diagram 1, it doesn’t quite confirm Mesanovic’s specification for low‑frequency bandwidth of ‑3dB at 28Hz, however the few Hertz difference is well within the vagaries of low‑frequency measurement so I’m perfectly happy to accept Mesanovic’s spec over my measurement.

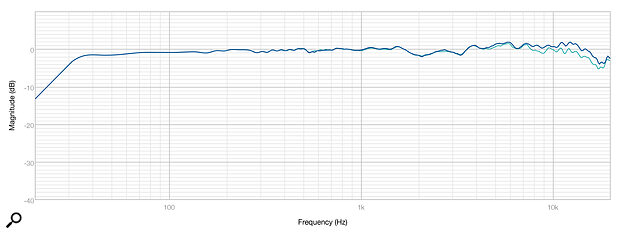

Diagram 2: The RTM10’s on‑axis and 20‑degree off‑axis response (blue and green traces, respectively).

Diagram 2: The RTM10’s on‑axis and 20‑degree off‑axis response (blue and green traces, respectively).

Diagram 2 illustrates the RTM10’s axial response again, but this time overlaid with a response taken 20 degrees off‑axis horizontally. Again, this is an impressive result. The horizontal off‑axis response shows just a gentle deviation from the axial response as frequency increases, with no significant discontinuities. Horizontal dispersion, however, is much easier to manage than vertical, especially when a pure ribbon tweeter is involved, and Diagram 3, illustrating the axial response overlaid with ±20‑degree vertically off‑axis curves, shows a rather different result. Along with the expected reduction in high‑frequency output from the ribbon tweeter (the ‑20‑degree curve dips more severely because moving the measuring mic off the perpendicular also places it relatively further away from the tweeter), a noticeable suck‑out appears around the midrange to tweeter crossover frequency. The suck‑out is almost certainly a result of phase cancellation in the overlap between the midrange driver and tweeter. Listening will reveal if it’s an issue subjectively.

Diagram 3: The RTM10’s axial response (blue), and the response measured 20 degrees above (green) and below (orange) axis.

Diagram 3: The RTM10’s axial response (blue), and the response measured 20 degrees above (green) and below (orange) axis.

Before I get to listening, there’s one more FuzzMeasure diagram to describe. Diagram 4 illustrates the effect of the RTM10 boundary compensation EQ options. The response curves confirm the specification of ‑2 and ‑4 dB, however the slight surprise is that the boundary EQ only operates from 100Hz downwards. My feeling is that for it to be useful and help a wide‑bandwidth monitor such as the RTM10 work in more bijou studio spaces, boundary EQ ought to operate from an octave or more higher.

Diagram 4: The flat, ‑2dB and ‑4dB boundary EQ options.

Diagram 4: The flat, ‑2dB and ‑4dB boundary EQ options.

Listening In

When I describe my subjective response to a monitor I traditionally start with the bass. This time, I’m going to focus on the other end of the spectrum — and that’s because the RTM10 tweeter is extraordinarily impressive. It’s so good you somehow don’t notice it at all. In comparison to a conventional dome, or even AMT‑style tweeters, the RTM10 unit seems almost completely without artifice. It’s as if there’s no transducer between the listener and the audio. It’s really that exceptional and I’ve heard, or perhaps not heard, very few tweeters pull‑off a similar trick. Everything is explicitly audible except, ironically, a tweeter. There is a ‘but’, however, and it’s that the RTM10 tweeter is, as expected, noticeably directional vertically. Listen away from the perpendicular axis and some of the magic dissipates as the top end of the tweeter falls away and the midrange suck‑out becomes audible. That said, I’d argue that for concentrated nearfield monitoring, where you’re listening from a consistent axial position, the quality of the RTM10 outweighs any vertical off‑axis inconsistencies.

The RTM10 tweeter is extraordinarily impressive. It’s so good you somehow don’t notice it at all.

Moving away from the tweeter for a moment, in overall tonal balance terms, and despite its very flat measured axial frequency response, the RTM10 sounds subjectively a little warm to my ears. I wonder if this is a result not only of the tweeter’s restricted vertical dispersion resulting in a slight lack of high‑frequency energy in the room, but also a result of the tweeter sounding so natural and unforced that I was not so conscious of its contribution?

The slightly warm balance is not a significant issue, as it can be easily learned and it certainly means the RTM10 is an easy long‑term listen. A second reason that slightly warm balance is no problem is that the great inherent detail and clarity provided by the RTM10’s midrange driver (and complete lack of resonant cabinet panel‑based coloration) makes overall tonal balance less of an issue. One of the reasons for voicing a monitor to display a prominent upper midrange and tweeter balance is that it can mask lower midrange coloration. If there’s little or no coloration, a warmer, more natural balance is more feasible. This was always the principle on which BBC monitors were designed and why the BBC monitor designers worked so hard on cabinet construction in order to minimise tonal coloration effects on voices and orchestral instruments. In some respects I was reminded of a classic BBC balance in the RTM10. Needless to say, perhaps, in midrange detail and imaging terms, the RTM10 is up there with some of the best. In those respects it’s a hugely effective mix tool.

I’ve left RTM10 bass to last but it too is worthy of far more than the paragraph or so I have left. The low end sounds easily as extended as the ‑3dB at 28Hz spec would suggest. It’s genuinely in subwoofer territory and, from a viable nearfield monitor‑sized package, that’s quite some achievement. The bass is also unmistakably closed‑box in subjective character, with unequivocal pitch, timing and dynamic qualities. It can play extremely loud too. If there’s a ‘but’ here it’s that RTM10 bass is so capable that I think it’s likely to overwhelm all but the largest and best‑behaved of studio rooms. Unless your room falls into that kind of category, I suspect using a room optimisation product such as Sonarworks, ARC, Trinnov or Dirac Live Studio would be almost obligatory, especially as the RTM10’s boundary compensation EQ didn’t really do the trick for me, even at its ‑4dB setting. To my mind the boundary EQ really doesn’t kick in at a high enough frequency.

The litmus test for me with a pair of review monitors is often to consider if I was sorry to see them leave. That was definitely the case with the RTM10s. They’re quirky in that they are highly sensitive to listening axis, but sit and listen in the right place and I can almost guarantee you’ll be completely hooked. If you have the budget, and a room that can handle the prodigiously extended bass, you should undoubtedly hear them.

Alternatives

The RTM10 is up against some really impressive monitors and if you’re lucky enough to be considering a pair you should probably also hear the Kii Three, Ex Machina Pulsar, Genelec 8351B, ATC SCM25A, Neumann KH420, PSI A23M and PMC TwoTwo8.

Pros

- Remarkable, addictive tweeter performance.

- Very extended and capable closed‑box bass.

- Natural, detailed uncoloured midrange balance.

Cons

- Vertical dispersion quirks demand care in listening position.

- Bass likely to overwhelm some small rooms.

- Boundary EQ not as effective as it might be.

Summary

It’s monitors like the RTM10 that keep me interested. It’s quirky, but at the same time it’s completely addictive and could easily be the only monitor you’ll ever need. I can’t wait to hear what Deni Mesanovic does next.

Information

£7499 per pair including VAT.

KMR Audio +44 (0)20 8445 2446

$7499 per pair.