The PlayScore 2 app makes it almost unbelievably quick to scan musical notation.

PlayScore 2 is an iOS and Android app that performs OMR (optical music recognition) via a device’s camera or graphics‑type file import. It can then immediately play that music, with some basic sound and mixing options, and also save and export it in a variety of formats such as MusicXML. It’s developed by Oxford‑based Organum Ltd and Dolphin Computing, some of whose work underpins Neuratron’s PhotoScore and NotateMe Mac/PC apps (which I reviewed in the August 2021 issue of SOS), so it’s far from an upstart.

PlayScore’s home screen shows all your documents, which are always locally stored, with a green ‘OK’ dot indicating the score capture is of good enough quality to work with. Photo and file import buttons are at the bottom-right.In principle OMR might seem simple. In reality, it must be anything but, because music notation is such a complex and relentlessly non‑standard business, and the variance in basic appearance from a 1930s orchestral score to a 2020s pop lead sheet, say, is mind‑bogglingly huge.

PlayScore’s home screen shows all your documents, which are always locally stored, with a green ‘OK’ dot indicating the score capture is of good enough quality to work with. Photo and file import buttons are at the bottom-right.In principle OMR might seem simple. In reality, it must be anything but, because music notation is such a complex and relentlessly non‑standard business, and the variance in basic appearance from a 1930s orchestral score to a 2020s pop lead sheet, say, is mind‑bogglingly huge.

But when it works, this sort of music scanning can be really valuable to many different kinds of musicians. PlayScore 2’s instant playback could help those who don’t read music to learn material. It can do ‘music minus one’, muting a solo line or individual parts, so that bands, ensembles and choir members could use the app for remote learning and rehearsal. A scrolling playback cursor and looping feature help greatly with this. Then there’s the potential for the app to be a scanning ‘bridge’ to heavyweight scoring apps like Sibelius, Dorico and Finale. It could remove hours of note‑entry drudgery when transcribing material. Of course, for this purpose there have been flatbed scanner‑based systems available for many years (like PhotoScore, which I just mentioned), but an app/camera‑driven solution like this could be a whole lot quicker and more convenient.

Shoots, Scores...

Revealed with a drag of a horizontal divider, various Document settings control aspects of playback, analysis and file export. You can set a score title and add composer info too.Putting PlayScore 2 into use is disarmingly simple and quick. The app starts up on a sort of library page, which shows miniaturised first pages of any scans you’ve done in the past, and which can be sorted by date, title or composer. Making a new scan is then a single button tap away; this gives you a typical live camera view overlaid with grey guides that assist with page alignment. PlayScore 2 detects when you’re holding your device horizontally, as if to scan music that’s lying on a desktop, and warns you that standing the music up can give better results. It’ll still let you capture like that though if you have to. And then it’s a case of just lining up your score page, in portrait or landscape orientation, and pressing the shutter button.

Revealed with a drag of a horizontal divider, various Document settings control aspects of playback, analysis and file export. You can set a score title and add composer info too.Putting PlayScore 2 into use is disarmingly simple and quick. The app starts up on a sort of library page, which shows miniaturised first pages of any scans you’ve done in the past, and which can be sorted by date, title or composer. Making a new scan is then a single button tap away; this gives you a typical live camera view overlaid with grey guides that assist with page alignment. PlayScore 2 detects when you’re holding your device horizontally, as if to scan music that’s lying on a desktop, and warns you that standing the music up can give better results. It’ll still let you capture like that though if you have to. And then it’s a case of just lining up your score page, in portrait or landscape orientation, and pressing the shutter button.

At this point, often with no delay at all, your score will start playing back with default piano sounds for each stave. Super‑convenient if you just want to hear it, but playback can also give an indication of how accurate the capture has been in general, because if it sounds wonky then inevitably the capture and subsequent analysis was flawed in some way.

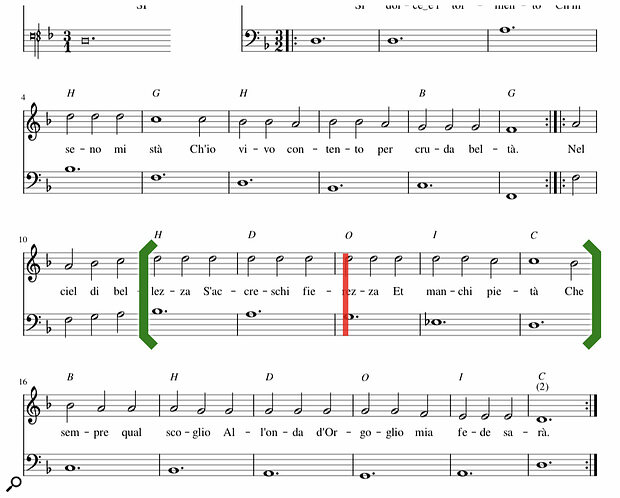

Tapping directly on the on‑screen score, with its scrollable pages, repositions a red playback cursor that scrolls smoothly during playback. Tapping and dragging, meanwhile, sets up a playback loop that snaps to bar line boundaries, indicated by green brackets. These loops can straddle pages, but the touch interface is not flawless in this respect: on my relatively small phone screen two adjacent pages seemed to be the limit. The feature seems best suited for looping just a few bars, and for that it works fine in almost all circumstances. Oh, and there’s also a count‑in feature of up to 10 bars, apparently currently only for iOS, which works well.

With at least one page captured you can then add additional pages to the same document (assuming you have a valid PlayScore subscription, which unlocks this ability). Or you can manipulate pages in various ways, including recapturing them, shuffling their order, adjusting cropping and rotation or adding masks, which is ideal if you only want to work with a small part of a printed page.

A part of a score shown during playback: the red playback cursor indicates current position, and the green brackets show a playback loop is active. PlayScore’s ‘mixer’ page is basic, and only ever refers to staves by number, but it does the job.

A part of a score shown during playback: the red playback cursor indicates current position, and the green brackets show a playback loop is active. PlayScore’s ‘mixer’ page is basic, and only ever refers to staves by number, but it does the job.

Playback options include overall tempo adjustment (10 to 600 bpm), sound selection (from 19 orchestral‑leaning instruments), volume and transposition for each stave, dynamic range, and a rhythmic swing option. There’s also a very welcome ‘Split Staves’ option, which gives you individual mix control over voices printed in stem up/down pairs on a single stave, as is common in two‑stave SATB choral scores, for example. And for the purposes of scans destined for MusicXML export, lyrics and text scanning can be enabled if you need it. Two text fields for title and composer metadata assist with filing and sorting within the PlayScore 2 app, and the title also determines the file name of any scores you export.

Playback options include overall tempo adjustment (10 to 600 bpm), sound selection (from 19 orchestral‑leaning instruments), volume and transposition for each stave, dynamic range, and a rhythmic swing option. There’s also a very welcome ‘Split Staves’ option, which gives you individual mix control over voices printed in stem up/down pairs on a single stave, as is common in two‑stave SATB choral scores, for example. And for the purposes of scans destined for MusicXML export, lyrics and text scanning can be enabled if you need it. Two text fields for title and composer metadata assist with filing and sorting within the PlayScore 2 app, and the title also determines the file name of any scores you export.

App subscribers get to import graphics‑format scores as well as using the camera. Indeed you can mix photo and graphics pages within a single document if you wish. For me, testing on a recent iPhone, the default location from which graphics could be imported came up as my iCloud drive. Local storage was also accessible though, and indeed various web document services such as Dropbox and OneDrive. As you might expect, JPG or TIFF documents are regarded as single pages. For multi‑page PDFs, in the Professional version, a simple interface lets you preview the contents and choose the first and last page to open, so you can easily cut out title and preface material. Essentially a green light to fill‑yer‑boots at copyright‑free score repositories like www.imslp.org.

Play & Learn

The disarmingly simple, intuitive interface belies some formidable music scanning abilities: this little app is capable of really impressive stuff.

This could be a typical workflow for many users. First, PlayScore running on an iPhone is used to import a multi‑page PDF, with the blue bars controlling page boundaries. Then, exported via AirDrop to a Mac, a generated XML file is opened in Sibelius. This raw, uncorrected import shows how impressively accurate PlayScore’s basic note and text capture can be, and also how some things get misinterpreted. ‘CODA’ anyone?My first experience of using PlayScore 2, in its camera‑driven Professional guise, was to photograph a six‑page instrumental score, with keyboard and melody line staves and several key and time‑signature changes, so that I could export it to Sibelius and transpose it up a tone. In about a minute flat the job was done, and with almost complete accuracy. The export process was easy, and Sibelius opened the XML file without any difficulty. Incredible! If only other aspects of my musical life would go so swimmingly...

This could be a typical workflow for many users. First, PlayScore running on an iPhone is used to import a multi‑page PDF, with the blue bars controlling page boundaries. Then, exported via AirDrop to a Mac, a generated XML file is opened in Sibelius. This raw, uncorrected import shows how impressively accurate PlayScore’s basic note and text capture can be, and also how some things get misinterpreted. ‘CODA’ anyone?My first experience of using PlayScore 2, in its camera‑driven Professional guise, was to photograph a six‑page instrumental score, with keyboard and melody line staves and several key and time‑signature changes, so that I could export it to Sibelius and transpose it up a tone. In about a minute flat the job was done, and with almost complete accuracy. The export process was easy, and Sibelius opened the XML file without any difficulty. Incredible! If only other aspects of my musical life would go so swimmingly...

I subsequently fired all manner of stuff at PlayScore, from pop lead sheets with lyrics to piano concertos, both via my iPhone camera and graphics import. Often the results were similarly impressive. The app recognises all standard notation symbols and conventions, and can cope with double sharps/flats, tuplets (up to septuplets), various kinds of staff and system bracketing, repeat bar lines and first/second‑time endings, bars straddling systems and pages, anacruses (partial ‘upbeat’ bars), all manner of dynamics, ornament and articulation signs, as well as tremolos, fingering, slurs, lyrics and text‑based chord symbols. With the iPhone camera I got good results from scores that had more than the recommended upper limit of staves per system. I also saw some impressively robust handling of multi‑voice staves and cross‑staff figures. This all has the potential to play back (and export) without fuss, and the onboard sounds, although entirely preset in nature and limited in number, are fine for simple mockups. Every now and then I heard some playback stutters, but it’s hard to know whether that’s a sound‑engine/phone glitch or just caused by a flawed interpretation of the musical content. With simpler material it never happened.

That old premise of ‘garbage in, garbage out’, though: well, it seems to have special resonance for music‑scanning apps like PlayScore 2. If you import a pristine, perfectly perpendicular PDF generated from an engraving application, you can be quite confident that PlayScore will do a cracking job. But if you’re taking a photo, and your source material is scruffy (or worse), or your lighting, technique or indeed camera is sub‑par, then the extracted notation data is likely to be shot through with errors, or big gaps.

Tapping the ‘?’ icon gets you these speech‑bubble help overlays, which are for the most part very clear. Incidentally, this piano piece, with its rather complex multi‑voice and cross‑staff notation, was handled very well by PlayScore 2, with just a few missing notes and markings, and some errant slurs.Actually, the capture and analysis process is amazingly tolerant of photos that aren’t quite straight, of non‑flat pages (and hence wonky staves), and other drawbacks too, but there’s a limit. And it’s fascinating how quickly it can be reached. For example, printed originals which have note stems that are even microscopically disconnected from noteheads or beams, or which in other ways are a bit ‘spidery’ or shadowy, are likely to throw the recognition process into chaos. These scores might look entirely clear and acceptable to a human player, but OMR clearly has different standards. By the same token, handwritten notation or even Real Book handwritten‑style typefaces are basically a non‑starter. And in general the older the notation style, or the more specialist the symbols used, the less success you’ll have. Same goes for pencil‑annotated scores: you’ll probably want to tidy those up first with an eraser. For purely photo‑related problems, a quick recapture of a page will often improve the situation markedly. But if problems persist the only things to tinker with are a couple of Advanced Settings sliders which control some kind of ‘sampling’ resolution and image brightness. They’re far from a sure‑fire fix.

Tapping the ‘?’ icon gets you these speech‑bubble help overlays, which are for the most part very clear. Incidentally, this piano piece, with its rather complex multi‑voice and cross‑staff notation, was handled very well by PlayScore 2, with just a few missing notes and markings, and some errant slurs.Actually, the capture and analysis process is amazingly tolerant of photos that aren’t quite straight, of non‑flat pages (and hence wonky staves), and other drawbacks too, but there’s a limit. And it’s fascinating how quickly it can be reached. For example, printed originals which have note stems that are even microscopically disconnected from noteheads or beams, or which in other ways are a bit ‘spidery’ or shadowy, are likely to throw the recognition process into chaos. These scores might look entirely clear and acceptable to a human player, but OMR clearly has different standards. By the same token, handwritten notation or even Real Book handwritten‑style typefaces are basically a non‑starter. And in general the older the notation style, or the more specialist the symbols used, the less success you’ll have. Same goes for pencil‑annotated scores: you’ll probably want to tidy those up first with an eraser. For purely photo‑related problems, a quick recapture of a page will often improve the situation markedly. But if problems persist the only things to tinker with are a couple of Advanced Settings sliders which control some kind of ‘sampling’ resolution and image brightness. They’re far from a sure‑fire fix.

I saw a few other specific limitations too, including the handling of multi‑stave scores that start out with all instruments/staves shown in the first system, but which have some of those staves hidden in subsequent systems. For those, PlayScore 2 is not smart enough to maintain the relationship between hidden staves and its initial allocation of line numbering and playback instruments, even when abbreviated stave naming is present. In a similar vein, it’s a shame that in the onboard mixer and sound chooser staves are only ever numbered, not named: for bigger scores that feels fiddly.

Conclusion

The above issues aside, with a little familiarity — and perhaps also a reasonable moderation of expectation — PlayScore can give results that are miraculously, impressively accurate. Easily as good as anything else currently available, and frequently achieved with less fuss. For the asking price the performance seems almost magical. I often couldn’t believe my eyes when lead sheets I’d snapped only seconds before came up with all chord symbols and multi‑verse lyrics intact. What’s great, too, is the speed and ease with which different, alternative captures can be tried out when you do meet problems. Try doing that with a flatbed scanner‑based system... Also, the very good onboard help system, and even fuller documentation on the web, emphasises that ‘quick and dirty’ is probably not going to cut it, and guides new users towards good practice.

PlayScore 2 is a fabulously useful, easy‑to‑use app that will appeal to all sorts of musicians.

So I can’t find much to fault: PlayScore 2 is a fabulously useful, easy‑to‑use app that will appeal to all sorts of musicians. You can try it out for nothing, and unlock advanced features for short periods if required, for about the price of a coffee and cake. It’s an example of really impressive tech implemented with a very light touch, in a way that really serves the user, at a low cost. I for one am always happy to have things like that around.

Copyright

PlayScore 2 makes it very easy to copy any musical score you point it at: and that can include copyright material. Legally, you mustn’t. Practically, it would be very useful to be able to photograph a song, say, and transpose it to better suit your voice. Trees falling in the forest, etc, etc...

Also interesting is that PlayScore‑generated MusicXML and MIDI files may only be used non‑commercially, unless you approach the developers to talk about licensing. So don’t get any ideas about selling MIDI files of your Scriabin symphony collection without checking the legalities first.

Requirements & Cost Options

To run PlayScore 2 you need a device with Apple iOS 12.4 (or later) or Android 6.0 (or later) and a built‑in camera of minimum 5MP resolution. It should also run on Apple Silicon Macs but you might have to think laterally about camera capture unless the majority of your work is with graphics import.

Playscore’s developers say that good cameras will support scores using up five or six staves per system, but that there’s no upper limit when importing a PDF that has been directly generated from an engraving app.

As for purchasing options, PlayScore 2 is actually free to download at first, but has limited functionality until you unlock features with either a ‘Productivity’ or ‘Professional’ subscription, available for periods of one month or one year. The cheapest option, a Productivity month, is £5.99$4.99, while a fully‑featured Professional year is only £26.99$26.99. That seems reasonable compared to the up‑front cost of the desktop‑based competition.

To sum up the differences between the free and subscription options, the unpaid app gives you fairly basic scanning: single pages only, of one‑ or two‑stave music, and no support for graphics file import. But you can still share native‑format ‘.playscore’ documents with other users and, very helpfully, open and play back complex multi‑page documents saved from a paid tier. This lets a band leader with a PlayScore 2 subscription, for example, distribute practice material to other band members running the free version.

Productivity, the cheaper paid subscription tier, unlocks multi‑page, multi‑staff and JPG/TIFF scanning, transposing instrument handling, and MIDI file export. Then Professional, for only a little more money, adds multi‑page PDF import as well as the MusicXML export that is vital if you’re primarily regarding the app as an OMR front end for a fully‑fledged engraving application.

Pros

- A fabulously useful instant playback/practice tool for printed scores.

- Also makes a convenient capture/scanning bridge to another engraving application.

- Can handle sophisticated and complex notation.

- Easy and very fast to use.

- The subscription‑based purchase is affordable and flexible, but even the free version is useful.

Cons

- No way to tackle issues with image capture, and potentially scrambled data, other than via re‑capture.

- Soundset is small and doesn’t include any percussion instruments (amongst other things).

Summary

A powerful optical music recognition app for iOS and Android delivered in a phenomenally user‑friendly form, at an equally phenomenal price.

Information

See ‘Requirements & Cost Options’ box.

Free, with in‑app purchases.