Never one to rest on his laurels, Roger Linn’s latest creation aims to bring unprecedented expressivity to MIDI musicians.

There are certain things in music technology that many of us take for granted. One is that MIDI controller keyboards are just that: keyboards. They use moving key–levers, with a tried and trusted 12–semitone layout, and what differentiates one from another is essentially size, build quality, and the number of real–time controls (knobs, wheels and sliders) they’re equipped with.

Times are changing though. Guitar– and wind–based MIDI controllers have been available for years of course, bringing with them a whole new set of expressive possibilities (and limitations...). More recently London–based ROLI have been making a splash with their Seaboards: silicon–surfaced piano–layout controllers capable of multi–axis touch sensing and polyphonic aftertouch.

And now comes another distinct alternative in the form of the LinnStrument. Its designer, Roger Linn, is a serial innovator. He designed the first programmable, sample–based drum machine in 1979, which arguably changed forever several fundamental aspects of music production. Since then he’s worked with Akai on their MPC workstations, put out the ground–breaking range of AdrenaLinn guitar effects processors, and more recently collaborated with Dave Smith Instruments on the Tempest drum machine. The LinnStrument is his latest product, which once again looks set to challenge the status quo. It aims to deliver a degree of expressivity and real–time performance potential that isn’t normally associated with moving–key controllers and synths. Roger says he’s on a mission to “save the note”, in a world where computer–based producers increasingly deal in the currency of pre–packaged loops and patterns, at the expense of soulful, individual musical performances. Could this new controller really turn things around?

Gridlock

Let’s get down to basics: this is not a keyboard. There aren’t any obvious moving parts. It doesn’t resemble a piano keyboard and can’t be made to virtually. The playing surface is instead a grid of 200 little squares, each 17 x 17 mm, arranged in eight rows of 25. Shallow troughs, 2mm wide, separate each square from its neighbours, and as the edges are crisply squared–off they’re easy to sense with the fingertips. The surface is a continuous sheet of 2mm thick silicone rubber, hard to the touch but compressible by 1mm, and translucent enough to let embedded multi–colour LEDs shine through. It’s set in a chassis made of steel and aluminium, with cherry wood sides, eight configuration buttons at one end, and a panel with various sockets at the other.

All very well, but how do you actually play it? Well, having no sound engine of its own the LinnStrument is a pure controller, and you’ll need to hook up a hardware synth via the five–pin DIN MIDI socket, or a computer, tablet or phone via USB. Then, touching the silicon surface with the fingers, each square generates its own MIDI note message, just like an individual key on a piano–style controller. Each row of squares is laid out in semitone steps (ie. as a chromatic scale), and that’s not adjustable. The interval between the 8 rows can be changed though. By default it’s 5 semitones (a perfect fourth), like the lower four strings in standard guitar tuning. But it can be set to many others, including a violin/mandolin–like perfect fifth, or octaves. A guitar tuning (with a major third amongst mostly fourths) is also available on the top six rows, with more fourths underneath.

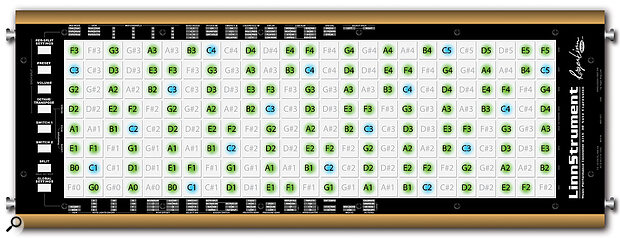

It’s fair to say the LinnStrument is closer in conception to stringed–instruments, with its ‘courses’ of notes, than it is to the piano. The programmable LED backlights add to this impression: they act as visual guides to the pitches you’re triggering rather like the dots or diamonds used to mark individual guitar frets. Like stringed instruments too, there’s quite a bit of overlap of pitches between the rows (in most tunings). That gets revealed very clearly as you play, because by default any pads at the same pitch as one you’re touching light up.

But here’s the really big thing. Every square (I’ll call them pads from now on) is sensitive to initial strike velocity, X– and Y–axis fingertip drags, and Z–axis pressure changes on an individual basis. X–axis drags generate pitch–bend data, so you can wobble a finger left and right to generate vibrato for example. Y–axis front/rear drags within a pad generate another data stream. And it’s the same for the aftertouch–like pressure. This of course explains why the LinnStrument has no pitch–bend and mod wheels: because the same data they’d generate, and much more besides, can be generated right from the playing surface itself. Like ROLI’s Seaboard and other ‘expressive’ controllers, the LinnStrument is capable of true polyphonic aftertouch, and will separate out its MIDI data streams so that an expression–heavy right–hand solo (to give just one example) has no effect on a chord held with the left hand.

This diagram shows the pitch layout and guide lights for a LinnStrument in standard fourths row tuning. The pads span a five octave range, with all Cs in blue and other natural notes in green. It’s all under user control though: different tunings, and more or fewer lights, in a variety of colours.The only limitations of the multi–touch sensing is that it’s strictly one–finger per pad, and touches on adjacent pads can’t be nearer than 5mm. Also, a fourth touch in a single vertical column, or that forms a fourth corner of a rectangle, gets ignored. I didn’t find these situations came up in normal playing though. Nor did the limitation that you can only play 50 notes simultaneously, as that’s about 40 more than I have fingers...

This diagram shows the pitch layout and guide lights for a LinnStrument in standard fourths row tuning. The pads span a five octave range, with all Cs in blue and other natural notes in green. It’s all under user control though: different tunings, and more or fewer lights, in a variety of colours.The only limitations of the multi–touch sensing is that it’s strictly one–finger per pad, and touches on adjacent pads can’t be nearer than 5mm. Also, a fourth touch in a single vertical column, or that forms a fourth corner of a rectangle, gets ignored. I didn’t find these situations came up in normal playing though. Nor did the limitation that you can only play 50 notes simultaneously, as that’s about 40 more than I have fingers...

There are a few further ways of laying out the playing surface. First, it can be split, flexibly, into left and right areas, each transmitting on their own MIDI channel ranges and having independent row tunings if you like. Second, one side of a split (or indeed the whole surface) can be turned into a bank of virtual faders, like left–to–right drawbars, which generate MIDI CC messages. Also, the lowest row can be dedicated to another task, such as becoming a sustain bar, a strum strip, or a controller for on–board retriggering and arpeggiator functions. Polyvalent, man! But before I get on to describing how it all feels musically, here’s a bit more detail about the LinnStrument’s hardware and software design.

Physical

Overall dimensions of the LinnStrument are 570 x 209 x 25.4 mm, or 22.4 x 8.22 x 1 inches. It weighs about 2.3kg, or 5lbs. Purchasers receive the unit in a close–fitting padded soft case, with a USB cable and a welcome letter signed by Mr Linn himself. My review unit was also signed, on a little sticker on the base.

Of interest to some will be screw–in studs that let you mount a guitar strap and seize your LinnStrument in keytar/washboard fashion. As battery powering or wireless MIDI isn’t built–in you’ll have to temper dreams of prancing from one side of a stadium stage to the other with a healthy dose of reality. But shoulder mounting is a fun option to have available for sure. Used flat on a desk, foam pads on the base keep the unit still and planted.

Connections to the outside world consist of a quarter–inch footswitch socket, a USB B–type socket, MIDI in and out on five–pin DINs, and a power inlet. They’re all reassuringly firmly attached to the metal chassis and don’t wobble about.

Single or dual switch–type pedals can be attached, and the tests I made with a couple of common or garden sustain pedals revealed they work as expected.

The class–compliant USB connection handles MIDI for typical computer setups, and can also power the LinnStrument. Indeed, the power requirements are so minimal that it’ll work quite happily hooked up to a recent iPad or iPhone, with a Lightning socket. I tested with an iPhone 6, via an Apple Lightning to USB adapter, with total success. There’s a special low–power mode for weedy USB hosts, which dims the LEDs slightly.

The presence of old–style MIDI sockets points to the potential for controlling hardware modular synths, which was apparently an important consideration in the whole conception of the product. The MIDI input lets the on–board arpeggiator slave to an external sync, and supports an obscure feature where MIDI controller messages can directly control the playing surface LEDs. Otherwise it’s not required for normal use.

As for the power inlet, it must be one of the most obliging in the business, working with AC or DC sources from 7.5 to 12V, 500mA or more, and with either polarity. However, it’s not required if you can power from USB, as most users probably will, even if they’re planning to use the five–pin DIN MIDI sockets. Consequently no power adapter is supplied.

Touch & Go

With the LinnStrument suitably plugged in and powered, new users will be keen to grasp the system for configuration and settings. The first thing to say is that there is of course no LCD screen, and no menu system. Nor is there any sort of dashboard or utility application that runs in OS X, Windows or any other OS. Instead, everything takes place on the front panel, via the eight labelled buttons at the left–hand side of the playing surface.

Two of the buttons, Switch 1 and Switch 2, simply turn features on and off in a toggle or momentary fashion. That includes octave transpositions, running and stopping the arpeggiator, or sustain. They’re designed to be used in real time, as you play. Split is similar, in that it turns the split playing surface on and off. If you hold it, though, a tap of a pad in the 8 x 25 grid sets the split point.

All the other buttons are there to program the LinnStrument in some way, and they disable the normal playing surface while they’re doing so. For example, tap Volume and the usual pitch guide LEDs vanish. In their place appears a line of LEDs in the row next to the button. Swipe your finger right or left along the row and more or fewer light up: it’s a virtual fader. At the same time the LinnStrument transmits corresponding MIDI CC 7 (volume) messages.

It’s a similar scheme for the Octave/Transpose button. Three virtual indicators appear, but this time in the form of bars extending left or right up to a few squares from pads (lit in blue) that represent the default, zero value. Swipe left or right and you can transpose by octave, semitone, or transpose just the guide lights.

Something slightly different occurs if you tap Preset. This feature sends MIDI Program Change messages, to switch presets on an external synth. To let you select a precise value in the range 0-127 the playing surface LEDs now display numbers in huge dot–matrix–style digits. Unexpected, funky, and very clear! Swipe left or right anywhere on top of the digits and the displayed value changes.

In terms of connectivity the LinnStrument offers MIDI I/O, a USB port and a quarter–inch socket for a footswitch. Nearly all other configuration is done via the outer Per–split Settings or Global Settings buttons and, if you press one, various pad LEDs effectively become status indicators, corresponding with the screen–printed labels just above and below playing surface.

In terms of connectivity the LinnStrument offers MIDI I/O, a USB port and a quarter–inch socket for a footswitch. Nearly all other configuration is done via the outer Per–split Settings or Global Settings buttons and, if you press one, various pad LEDs effectively become status indicators, corresponding with the screen–printed labels just above and below playing surface.

Say you want to change the pitch-bend range. You’d start by pressing Per–split Settings. Then look for the Bend Range label along the top of the front panel — it’s seven columns along. Four printed options are shown: +/– 2, 3, 12 or 24 semitones, and the current setting is shown by noting which pad (the first, second, third or fourth down) in the column beneath is lit. Changing the setting is then as easy as tapping one of the other three pads.

It’s an unfamiliar programming system, for sure, but actually it’s dead easy to grasp, and super–fast in use. Some aspects were apparently the brainchild of Roger Linn’s collaborator and software designer, Geert Bevin, who has also worked on software for Moog Music and the Eigenharp, and runs the website www.expressiveness.org.

Certainly, the LinnStrument can be customised to a surprising degree, for different controller tasks, and it’s good to see that four configuration snapshots can be stored and recalled via the Preset button. And in case that’s not enough, the operating system is open source and can be downloaded from the LinnStrument web site.

Synth nerds amongst you might have already identified apparent limitations of the system. For example, the Y–axis touch response labels (ninth pad along) suggest that only CC1 and CC74 messages can be generated from front–rear finger drags. Certainly, those are useful preset options — CC1 for modulation wheel, and CC74 for brightness, typically controlling the filter cutoff in synths. But what if you’d prefer to generate another MIDI CC number? Here, some hidden functionality comes into play. If you hold the pad that corresponds to the CC74 label suddenly ’74’ appears in those big digits once more. Swipe left or right on top of them and you can choose any other MIDI CC number you like, or Poly Pressure, or Channel Pressure.

It’s the same, in fact, for many parameters that apparently have only a limited range of preset options, including bend range and Z–axis MIDI CC.

Give Life Back To Music

The LinnStrument’s grid design might seem, at first sight, pretty unpromising for expressive playing. But nothing could be further from the truth. Just a short time spent with the instrument reveals it’s overtly expressive, and remarkably responsive. Paired with a suitable sound generator (see the ‘Sound Sources’ box) the tactile nature of the playing surface can be explored.

The first impression is of how little give there is under the fingers — you’d be forgiven for thinking the rubber is completely inflexible. However, within the tiny 1mm of compression available to a held touch, the resulting MIDI data values (typically Poly Pressure or Channel Pressure) can be finely graded, with great repeatability. It’s quick too, with no discernible lag, and no difficulty tracking wild swings in pressure occurring in close succession. I can’t think of any moving–key controller with aftertouch response this good, certainly.

Velocity is a slightly different matter. With no moving keys to manipulate, or inertia to overcome, the initial touch on a LinnStrument feels percussive in nature. You might even say ‘dead’, like playing on a table top. Pianists have to leave behind notions of arm and hand weight, and focus more exclusively on the strength of their finger taps. And yet note velocity is also eminently controllable, with the whole range easily available. My only concern was that the very lightest finger taps I made wouldn’t trigger a note at all. There was a risk that gently–played passages would be peppered with missing notes. The LinnStrument is distinctly different to ROLI’s Seaboard in this respect: the nature of that design’s velocity response, and its much more deeply compressible surface, makes it easy to squeeze in from silence, as it were. However, with familiarity, and suitably programmed sounds, the same thing is achievable here: just in an alternative manner. (That said, Roger Linn says that the less compressible surface was a deliberate design decision, intended to improve rhythmic performance.)

The responsiveness to Y–axis finger drags is surprisingly good. Given that you might typically have only 6 or 7 mm available from initial strike position to the edge of the pad, smooth and easily gradable MIDI data streams just seem to flow out, smoothly spanning entire value ranges.

The LinnStrument’s interface centres around a grid of 200 17 x 17 mm square pads.

The LinnStrument’s interface centres around a grid of 200 17 x 17 mm square pads.

X–axis pitch response is arguably the most sophisticated aspect of the LinnStrument’s touch response. The idea, of course, is that fingertip wobbles and rolls within a pad result in vibrato, potentially as natural–sounding as if you did the same on a violin. However, players can also drag left and right along the rows, for bends, swoops, fall–offs, and portamento–like effects covering a much larger pitch range. Bend range settings of up to 96 semitones are available, and so long as you set up your sound generator with the same range then finger drags are properly graded — that’s to say, the number of semitone pads you drag over will equal the pitch deviation you’ll hear.

The clever thing here is that the pitches of all initial touches are by default quantized. It means that you’ll get an in–tune note no matter where you initially strike the pad that triggers it. Subsequent in–pad X–axis wobbles will then begin to generate pitch–bend data. But when you stop wobbling, regardless of whether your finger has finished up on the flat or sharp side of the pad, the LinnStrument quantises the held note back in tune again. The net result is that it’s hard to play the LinnStrument out of tune (unless you turn off quantizing), and yet it’s ever–sensitive to pitch inflections.

Throughout my testing I didn’t notice any difference in aspects of pad response between the centre and edges of the grid, and I felt the default sensitivities were really nicely judged. A firmware update, v1.24, was released after I’d said goodbye to the LinnStrument I’d been loaned for review, and that apparently improves some aspects of velocity response.

As for what it’s like to play actual music on the LinnStrument, well, it’s simultaneously fun, rewarding and, initially, challenging. As I mentioned earlier, the row ‘courses’ and pad ‘frets’ are likely to feel more familiar to guitarists than keyboard players. Certainly for me, with only the most rudimentary guitar technique, I was at first reduced to beginner–level prodding.

However, observing guitarists get going with the LinnStrument is a different matter: for the most part it seems to be really intuitive, somewhat like playing a Chapman Stick, it has to be said. And I found I too got to grips with it within a matter of hours: certainly well enough to play typical pop riffs, bass lines and chord parts, anyway.

A really important consideration here is that in nearly all its row tunings the LinnStrument is what you’d call isomorphic. Pitch relationships between pads, either along or across the rows, are identical regardless of starting position. Or to put it another way, it’s no harder to play in C# major, or any other key, than it is in C major. That offers some distinct advantages for transposing at sight, jamming with other musicians, and simply just getting fluent on the thing! There’s excellent support material at www.rogerlinndesign.com incidentally, including a hugely helpful diagram showing a variety of chord shapes and scale patterns for the default fourths tuning.

In expressive terms, controllers like the LinnStrument are a new dawn for finger–driven playing. The scope for instantaneous, intuitive, natural note shaping is colossal. Hearing a demo by an accomplished player can leave you in almost a state of shock. With some sounds, like pedal steel guitar, acoustic or fretless bass, or overdriven harmonica, you’d need a few careful listenings to be sure it wasn’t the real thing. Even good quality sampled or modelled flute, clarinet, and violin can sound convincing. That’s saying something, because played direct from keyboard controllers they usually sound dismally, laughably artificial. But the LinnStrument is at least as good for exploring purely electronic sounds. Being able to individually control note volume, timbre and vibrato within held chords opens up new options for pad, string and polysynth sounds, for one thing. It’s like having synth modulators available at the fingertips! At the same time, the potentially wide, controllable pitch bends encourage various Ondes Martenot and Theremin–like playing styles, polyphonically too, and make pitch wheels or one–size–fits–all portamento look like very poor relations. Inclusion of the virtual CC faders, arpeggiator, restrike and strum features add a lot too, and further differentiate the LinnStrument from other expressive controllers like the ROLI Seaboard.

Conclusion

Add everything together, and what we have here is a really ingenious new instrument design. The grid layout is flexible enough to support melodic, chordal and percussive playing in virtually any style of music. The ‘multi–dimensional’ expressive features encourage musical interactions that just aren’t possible with keyboard–based controllers (or, for that matter, most other kinds of MIDI controller). Yes, everyone is going to have to establish their own playing techniques and ways of working with the LinnStrument, but results do begin to flow quickly, and the process of learning is itself rewarding. The physical product is of top quality too — it’s a great bit of gear to have in the studio, with some real pedigree.

Exactly where it fits into various users’ setups and workflows: that’s an interesting question. It can act as a front end for MIDI sequencing work, but there are important caveats surrounding specific DAW and instrument compatibility that potential purchasers need to be aware of. It seems to come into its own as a live performance tool, and as a platform for routine–busting experimentation. Thinking more in terms of the audible ends, rather than the MIDI means, mightn’t be a bad idea generally.

Whatever your take on products like this one, we’re fortunate that there are more of them out there than ever before. They might just change the electronic music landscape. And whilst it’s one of the most original, the LinnStrument is also one of the very best.

Sound Sources

Expressive controllers like the LinnStrument seem to have so much going for them. But they have a dirty little secret too: their full expressive potential is only realised with certain DAW applications and virtual instruments.

In the case of the LinnStrument the full, unfettered experience is offered only when you turn on the channel–per–note mode, in which new note triggers are continually assigned their own MIDI channels. That ensures the pitch–bends, swells and Y–axis modulation applied to one note don’t end up applied to others happening around it. A single–channel mode is available, and is actually the factory default, but while it has a role for some monophonic sounds, and is generally more compatible, it’s not as flexible.

Then you need the right DAW. Logic Pro X, Cubase, Bitwig Studio, Reaper, Tracktion and GarageBand are currently the best choices, because they have the necessary multi–channel MIDI input capabilities. All of them make good plug–in hosts for live playing, but the way they record the LinnStrument’s MIDI and offer it up for subsequent editing varies from accommodating to awkward.

The likes of Live, Studio One, DP and Pro Tools are much less good. They require that you create multiple MIDI input tracks for each virtual instrument you want to play: one track for each note of polyphony. Even then lots of tedious channel routing is required. Recording a performance would result in MIDI events strewn across all the tracks, so editing could be close to unworkable.

What of virtual instruments themselves? Several of Logic’s (including EXS24 and ES2) work well, as does Bitwig Studio’s bundled PolySynth. And here’s a run–down of solid third party options: U–he’s Bazille, Ace and Diva; Sonic Charge’s Synplant; FXpansion’s Strobe 2; and Aalto and Kaivo from Madrona Labs (makers of the expressive Soundplane controller). Omnisphere, Kontakt and Mach Five can be made to work in multi–channel fashion by having a single sound loaded into multiple parts, responding to different MIDI channels. And there’s are a couple of NI Reaktor gizmos out there (a user–created synth and a Reaktor 6 processing block). Finally I’ll mention the various VIs from www.samplemodeling.com, which are probably the current best bet for acoustic sounds, ideally driven from LinnStrument’s single–channel mode.

You can sum up this whole situation by saying that early adopters of expressive controllers need to be pretty open–minded and resilient. They might need to embrace unfamiliar DAWs and synths, and often there’s a bit of homework to do, experimenting with hardware and software settings. Life with the LinnStrument is not as easy as firing up any old DAW/instrument combo and playing it from a MIDI keyboard, and it’s probably not something for absolute beginners either.

At least in the case of the LinnStrument the support on offer (via the support pages on Roger Linn’s web site) is extensive, detailed and helpful.

Guided Play

While the LinnStrument may look ripe for repurposing as a step sequencer, it doesn’t do that. Being about as far from ‘expressive’ as you can get, and at odds with the whole ethos, it probably never will. However, there are ways you can deviate from a conventional playing style.

First, there are a couple of features related to the ‘Low Row’ functionality I mentioned in passing above. Restrike causes the lowest row of pads to become one big note trigger. Touch somewhere in it and any held notes above re–trigger. Strum is similar, except that it’s more suited to finger swipes along the lowest row, and only re–triggers a held note above when it passes the column it is in.

Second, there’s an arpeggiator, which will rhythmically re–trigger held notes in typical up, down, up/down and random orders, over a one to three octave range, or repeat them. You can set or tap a tempo, or slave to an incoming MIDI clock, and set the rate of arpeggiation to several useful musical values, straight and swung.

What’s really nice here is that new note velocities within arpeggiated patterns can be varied by changing the pressure of the held pads. And you can further opt to make the lowest row a rate modifier: with a chord arpeggiating in the normal way, finger swipes left or right momentarily decrease or increase the rate.

Pros

- An entirely new type of musical instrument: exciting!

- Grid–based pad layout supports playing in virtually all styles and textures.

- Multi–axis expressive touch features are compelling, but easy to grasp and control.

- Out–of–the–box familiarity for guitarists, and an attainable learning curve for others.

- Many features extensively customisable, with an intuitive programming system.

- Super build quality.

- Much thought given to practicality, especially various power sources and so on.

Cons

- Requires initial practice and time from all users to get reliable, repeatable results.

- DAW and synth compatibility can’t be taken for granted.

- May not replace a keyboard controller for sequencing duties for many users.

- Purchase price, though entirely reasonable, is a serious outlay.

Summary

Weird and wonderful, the LinnStrument is a beautifully put together MIDI controller that has real musical potential. Various aspects of use and compatibility with the outside world require an open–mind and pioneering spirit, but its unique capabilities more than repay the effort.