Don’t have a great‑sounding room? Can’t turn your amp up to get the sounds you want? Want to turn down your speaker without sacrificing your tube amp’s tonality? Maybe this changes everything...

Universal Audio describe the OX rather prosaically as an ‘Amp Top Box’. That’s understandable, given that the full description is more like ‘reactive dummy load, stepped speaker attenuator, dynamically modelled digital speaker, microphone and room emulation... with wireless remote control app’!

Universal Audio describe the OX rather prosaically as an ‘Amp Top Box’. That’s understandable, given that the full description is more like ‘reactive dummy load, stepped speaker attenuator, dynamically modelled digital speaker, microphone and room emulation... with wireless remote control app’!

Overview

The OX is designed to accept a speaker‑level input from a tube guitar amp — there’s no amp modelling on board — whilst simultaneously offering a guitar‑speaker output via a variable attenuator, plus a digitally modelled speaker and microphone emulation, with effects, at its line outputs. In a studio setup, you can use the silent setting on the guitar speaker output to hear the exact signal you are recording on the studio monitors, and in a live setup, you can turn your amp up to where you want it, and your speaker down to where FOH wants it, whilst sending your preferred speaker and mic signal to the desk as an analogue line‑level or digital source.

Electric guitarists today have more options than ever before for both recording and live performance, with digital modelling and impulse response‑based speaker emulations having attained a level of authenticity that many players now find completely satisfying. The best ‘reactive’ dummy‑load attenuators now offer a true speaker‑like impedance curve to amplifiers and allow tube amps to be used with their ‘sweet‑spot’ settings without upsetting front‑of‑house engineers or home‑studio neighbours.

UA’s OX enters this market as something of a hybrid, being both attenuator/dummy load and speaker emulator in one box, with French company Two Notes Engineering’s Torpedo Studio dummy load and speaker emulator perhaps being the closest functional equivalent. Rather than use impulse responses — analogous to tonal ‘fingerprints’ of speaker cabinet and microphone combinations — UA have developed their own digital modelling process, which they state allows their emulated speakers to respond dynamically to changing input signals, as a real speaker would.

I have used impulse responses happily and successfully for a number of years now — for me and many other players, IRs changed the landscape of speaker emulation overnight from “meh” to “that actually does sound like a guitar speaker!” Extremely convincing though IRs can be, unless you have a hardware IR loader, you need to monitor something other than the sound you intend to end up with in order to achieve a latency‑free tracking setup, before applying the IR you want as a software process. The OX’s all‑in‑one solution means that the sound you hear as you’re playing is the sound you are recording, with negligible latency (under 3ms).

Of course, IRs have a fixed transfer characteristic — their tonal signature — and whilst you can always tweak them a bit with EQ and room simulation, I’ve never yet been able to get a single IR to fully imitate a real speaker’s whole range of responses. Like many others, I guess, I’ve ended up with a small library of IRs optimised for different pickup settings and levels of drive — when what I really want is something that gives the appropriate response to whatever I throw at it. Given UA’s deep expertise in both classic analogue studio gear and digital emulations of analogue gear, perhaps nobody was ever better placed to look beyond IRs to the possibility of a more dynamic, detailed speaker emulation technology.

Design & Construction

The OX itself is a seriously substantial unit, with a 15 x 5.5 x 8 inch metal housing featuring a stylish, slightly retro, wooden front‑panel trim. At over 14lbs, it feels like it ought to have an amp‑like mains transformer in it, but it actually has a 12V external DC PSU, albeit with a reassuringly robust four‑pin XLR locking connector. I’m guessing that the weight comes from the power soak of the reactive dummy load circuitry. I was delighted to see that there is no fan!

Speaker Volume offers a level‑controlled feed to a guitar speaker whilst Line Out governs the modelled speaker and mic output, with the room‑mic mix independently adjustable.

Speaker Volume offers a level‑controlled feed to a guitar speaker whilst Line Out governs the modelled speaker and mic output, with the room‑mic mix independently adjustable.

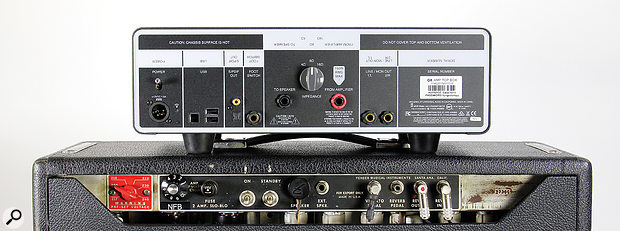

Despite the deep control available in the remote app, the front panel has just five knobs, and a nice cosmetic touch in the form of a classic amp‑like jewel power light. All the DSP resides in the OX itself, so once you’ve tweaked and stored a few settings that you like, you don’t need to keep the remote control app running. You can store six ‘rigs’ — complete combinations of speaker, mic and effects emulations — selectable from a six‑way rotary switch. Whatever the stored value, the amount of simulated room ambience can always be overridden by a dedicated rotary control. Another six‑way rotary determines the output level to a connected guitar speaker, with ‘none’ and ‘everything’ at the two extremes. Line out and headphone level (plus quarter‑inch socket) complete the simple and intuitive control line‑up.

Over on the back panel we find connections for a speaker‑level input from a tube amp (solid‑state amps are not advised), and a post‑attenuator output to a guitar speaker. A three‑way impedance switch allows the OX to present a 4, 8 or 16 Ω load, which should keep most amps happy. If you accidentally power up an amp without remembering to switch the OX on first, there’s a 16Ω ‘safety load’ that will take care of things while you figure out what you’ve done. It’ll also keep everything safe if you switch off the OX, or it loses power while an amp is connected. A pair of balanced/unbalanced quarter‑inch jack line outputs is where the speaker‑emulated signal and effects appear — the actual speaker output is unaffected — and there are also S/PDIF (RCA and optical) digital outputs, three USB ports and a footswitch connection. The USBs at present do nothing more than provide a route to software updates, but obviously hint at plans for future expansion, as does the presently ‘inactive’ footswitch socket. Actually, the footswitch does do something: connecting a simple make/break switch causes it to temporarily capture and replay a bit of input signal like a looper, which you can then use to audition cab and mic setups without having to keep playing. This seems to be undocumented, and I don’t know if it will survive the footswitch getting a proper function in future, but it’s actually quite useful!

The speaker connection on most combo amps won’t be long enough to reach the OX’s speaker output. To use the attenuator you will need to buy or fabricate a short male‑ to female‑jack speaker lead. Using a locking female jack makes this feel a bit more secure.

The speaker connection on most combo amps won’t be long enough to reach the OX’s speaker output. To use the attenuator you will need to buy or fabricate a short male‑ to female‑jack speaker lead. Using a locking female jack makes this feel a bit more secure.

On Test

The reactive dummy load/attenuator seemed like a good place to start testing. After all, the amplified life of the signal starts at the amp; if the amp isn’t behaving normally your chances of creating a convincing speaker emulation are inherently compromised. Dummy loads on most older attenuators tend to be purely resistive, which means their impedance is constant regardless of the frequency of the input signal. This is unlike a real speaker, which will always exhibit a significant amount of ‘reactance’ (variation of impedance with frequency). For an amp to sound and feel like it does when it is driving a speaker, its output stage has to be seeing something that closely resembles the impedance curve of a real speaker. The OX’s attenuator is a real gem, as far as I’m concerned. I felt no desire to start tweaking tone control settings on the amp as I went down the attenuation ranges, and that’s the biggest clue that the OX is keeping the amp happily convinced that it is driving a normal speaker at all settings. It sounds like there is a small amount of ‘voicing’ going on at lower output levels — I confirmed this by recording the low‑level signal and boosting it to the loudness of a recording of the minimally attenuated signal — but it is not at all extreme, and I think it is probably beneficial overall. It seems to give the quietest setting some girth, without which many might perhaps find it unusable. A couple of my amps were more affected by the attenuator than the rest, being a little darker at the highest attenuation setting, but not to the point where I wasn’t happy to use them.

The attenuation settings are stepped. To my ears and in my applications, they are entirely logical increments, but I suspect that, particularly in a live context, some might wish for finer increments at the top of the scale. Of course, most people’s ideal would be a fully variable pot, but that’s not an easy thing to achieve in an attenuator without compromising something else, such as the total range of attenuation available. These increments work for me — for recording, the speaker is off, and for stage, one‑notch‑down is just right for a pair of 6V6s into a single 12.

The App

So far, we’ve been all analogue, all hardware — all ‘real’ if you like. Connecting the two analogue line outs and firing up the app takes us into the OX’s parallel digital world. The app is exclusive to Apple operating systems, being available for iPads (iOS 11) or Mac OS (Sierra onwards) desktops. I’m tempted to say “at the moment”, but there is seemingly nothing to be had from UA on this, so I won’t speculate. If I were a confirmed ‘non‑Apple user’, I’d be disappointed in that situation. That said, one of the factory rigs that the OX ships with so perfectly fitted my tastes that I could still have made great use of this without ever firing up the app, so maybe Android and Windows guys should still check it out.

The OX can process the result of the modelled cab/speaker/mic sound with up to four simultaneous effects. These are derived from the company’s highly respected UAD platform, and on offer are a lovely‑sounding plate reverb, two different EQ types, a delay processor, and an 1176 FET compressor model.The app interface (see the ‘Wi‑Fi & The App’ box) shows you a graphic of your chosen cabinet and mic setup in a nice‑looking studio live room, with a small mixer in the lower half of the screen. The three mic channels — two close mics and one room mic — feed a stereo master fader, with each mic channel having mute, solo and hi‑pass filter switches, a pan pot, plus the ability to insert an EQ. The master channel sums all three sources and offers four‑band EQ, a lovely 1176 compressor emulation, a sweet‑sounding vintage plate reverb algorithm, and a versatile stereo digital delay with filters and modulation. Each processor opens into a UA‑style, graphic‑heavy, detailed editor. The mix controls on both reverb and delay could be better scaled to give a bit more resolution in the normal working ranges, I feel. One for a software update, maybe.

The OX can process the result of the modelled cab/speaker/mic sound with up to four simultaneous effects. These are derived from the company’s highly respected UAD platform, and on offer are a lovely‑sounding plate reverb, two different EQ types, a delay processor, and an 1176 FET compressor model.The app interface (see the ‘Wi‑Fi & The App’ box) shows you a graphic of your chosen cabinet and mic setup in a nice‑looking studio live room, with a small mixer in the lower half of the screen. The three mic channels — two close mics and one room mic — feed a stereo master fader, with each mic channel having mute, solo and hi‑pass filter switches, a pan pot, plus the ability to insert an EQ. The master channel sums all three sources and offers four‑band EQ, a lovely 1176 compressor emulation, a sweet‑sounding vintage plate reverb algorithm, and a versatile stereo digital delay with filters and modulation. Each processor opens into a UA‑style, graphic‑heavy, detailed editor. The mix controls on both reverb and delay could be better scaled to give a bit more resolution in the normal working ranges, I feel. One for a software update, maybe.

Using the pan controls in combination with the two outputs allows you some track allocation options: you can record the two close mics separately, with or without a little room mixed in, or, my favourite, choose a mono room mic and send it to one output while the two close mics are combined in the other channel. So long as you’ve remembered not to use any of the master effects, recording these two streams separately allows you to vary the amount of room mic in the context of your track when mixing. Personally, I prefer not to have much ‘baked‑in’ room ambience on a guitar signal, and would always rather add it as needed while mixing, but the OX room signals are so ‘just right’ that I find it worth recording them, even in mono, so long as I can give them their own output. Of course, four outputs, with separate close mics and a stereo room, or even three, with separate close mics and a mono room, would have been great. As it is, there are two — and I’ve really got no complaint about that. It is entirely manageable and versatile enough exactly as it is. Working with the OX for a couple of weeks I’m increasingly finding that anything that it won’t do simply pales into insignificance beside what it will.

The digital outputs are 24‑bit, with a fixed 44.1kHz sample rate. In my view, that is more than adequate to capture anything electric guitar related. Others may disagree. In practical terms, I think the only real benefit that a higher sample rate might offer is a lower latency — even the analogue line outs exhibit a small 2.77 millisecond latency because they are outputting a signal from a digital process. Under three milliseconds is insignificant when the rest of your process is entirely analogue, but you might want to bear it in mind if you start combining the line‑out source with a real mic signal. (The throughput from the attenuator to the real speaker is entirely analogue and therefore latency‑free.)

There are plenty of speakers and cabs to choose from — a 1x10, five 1x12s, a 2x10, five 2x12s, a 4x10 and four 4x12s — and any rig can have any combination of cabinet, mics and effects. (See the ‘Speaker Cabinets’ box.) The really interesting thing I found with the speaker cabinets is that the amp/speaker combinations that, in my experience, work best in the real world, tend to work best with the OX, too. And the speaker cabinets I tend to like and use the most are also the ones I prefer in the OX. Of course, this could mean I am just a bit unimaginative when it comes to adventurous pairings of amps and cabs, but it could also mean that the OX’s cabinets are uncannily accurate in their emulations of the real thing.

Some might say that the OX’s range of cabs leans slightly towards the vintage and classic end of the spectrum, but I don’t think of speaker cabinets as hugely genre‑specific. There’s no 4x12 with V30s, for example, but for me the right amp into any of the 4x12s will get me ‘that sound’, with a touch of EQ and compression. And, just as in the real world, even a single‑driver cab can be made to sound huge in a recording with the right amp and appropriate (virtual) miking.

The OX is specified for a maximum input of 150W RMS (200W peak) with a software selection of 50 or 100 Watts setting the basic operating range. As far as I can tell, nothing much happens if you mismatch this setting except that the output gets slightly louder or quieter, depending on which way you are mismatching. I certainly never felt I was anywhere near to clipping anything internally unless I was boosting with EQ a bit too much, or running the compressor output significantly above unity. Tempting as it may be to turn your tube amps ‘up to 11’, you don’t have to work with good attenuators and speaker sims for very long to realise that there are many amps that don’t actually sound that good when pushed to the limit. Most have a ‘best operating range’ where both preamp and power amp are driven to an optimum extent, but very rarely, in my experience, will that be in the top 10 percent of the volume scale.

The other speaker parameter is Speaker Drive — an intriguing process of gradual virtual ‘ageing’, through to level‑induced speaker distress at the top of the scale. The latter includes the phenomenon sometimes referred to as ‘cone‑cry’, which can exhibit as a ‘false harmony’ note or various forms of intermodulation distortion. It’s certainly convincingly authentic, but I can’t say that I particularly like to hear any cone‑cry (I accept that some people do) and personally I’d certainly never let a real speaker exhibit such effects for very long. The ageing effect to be found further down the Speaker Drive scale, however, is very subtle and eminently usable, softening the attack and smoothing the distortion a little, just like a favourite old speaker with a good number of miles on the clock.