If you're thinking of buying a PC soundcard specifically for HD recording, you'll find the market awash with models old and new. Martin Walker provides an overview of what's currently available. This is the first article in a two‑part series.

You might think it's easy to go out and buy a soundcard — after all, there are a lot of them about, and most claim to have superb audio quality, as well as a host of must‑have features, from complete on‑board samplers "rivalling stand‑alone models worth thousands of pounds" to wavetable synths with 64‑note polyphony, and digital recording and playback with up to 24‑bit converters. The amount of choice available is a problem in itself. Worse still, after you've spent long hours debating the relative merits of the models on your shortlist, you might discover when you actually try to buy one that the advertising is six months ahead of the R&D department, and that none can be had for love nor money. And some hi‑tech products have an alarming habit of being released before the software has had its final polish applied — it's not unknown to wait for six months after initial shipments for reliable drivers to appear. So here it is: the SOS guide to soundcards, to help you narrow down the options, steer you in the right direction, and point out possible pitfalls along the way.

If your ultimate goal is a DAT tape, DCC, or MD, look for a soundcard that provides a digital output.

Channelling Your Efforts

The first question is a major one, but not quite as straightforward as some people think — whether to buy a stereo or multi‑channel card. If you just want to do general‑purpose music recording on a budget, stereo will certainly be adequate, but what about the new breed of MIDI + Audio sequencers? Surely you need more than two playback channels to get the most from these? Well, not necessarily. The beauty of such applications is that they allow many audio tracks to be recorded separately, but then these are mixed down in real time to a stereo pair, which can be replayed using a stereo soundcard. The mixing is carried out internally, so as long as you only need to record a single mono or stereo source at once, you can achieve a multitrack software studio using only a stereo in/out soundcard.

So why are so many companies launching multi‑channel cards? Because although it is theoretically possible to transfer all the impressive rack‑mounting outboard effects into virtual equivalents in software form, to do it you would need a very powerful computer. Yes, there are some wonderful real‑time plug‑ins available to take over reverb duties, provide effects such as echo and flanging, and offer processes such as enhancement, compression and parametric EQ, but replacing even a small project studio's worth of effects would take more computer power than is affordable at the moment.

The first question is not quite as straightforward as some people think — whether to buy a stereo or multi‑channel card.

What you need is a way to use whatever analogue gear you already have, so that you don't lose the treatments you love so much. The answer is to hang on to your mixing desk, internally patch individual PC‑recorded tracks to the other soundcard multi‑channel outputs, and then connect these to the mixer input channels. Then you can still use whatever effect units you already have. The MIDI + Audio sequencer will normally provide a way for you to record the final stereo output from the desk back into the PC's stereo inputs, so that you end up with an additional stereo pair of tracks. This can be added to your final stereo mixdown with the other digitally recorded tracks inside the computer. You only need a single stereo soundcard input to do all this, but you may want four or eight output channels. You can, alternatively, use some of the additional outputs as effect sends to external gear, which again can have their return paths mixed down to stereo and added to the computer mix (although you may need to tweak the relative timing of these tracks slightly to compensate for any digital delays).

Slot Machines

Another big decision is whether to opt for an ISA‑ or PCI‑format soundcard. All PCs built in the last few years contain a selection of both of these types of expansion slots — there are normally three or four of each. The older ISA‑buss standard has been going a long time, but many of the recent soundcard releases are PCI. It has to be said that PCI is the standard of the future, since Intel seem determined to make our lives easier by trying to phase out ISA slots over the next few years. This would largely remove the installation problems that many of the older ISA cards have, particularly the ones that were designed before Plug and Play burst onto the scene to make our lives easier (allegedly). The buss frequency (how fast data can be moved about) for ISA cards is about 8MHz, and it has a data width (how many bits are transferred simultaneously) of 16 bits. Although this sounds huge, PCI has a higher buss speed of 33MHz, and a 32‑bit data width.

ISA soundcards can cope with multi‑channel data, but PCI can move this data at a much faster rate — and, obviously, anything that reduces the overhead of moving sound data about will leave more processor power for fancy reverb plug‑ins. However, sound quality is unaffected by which buss is used, and there are lots of excellent quality stereo soundcards (most of those covered this month) that use the ISA buss. As always, we can only buy what is currently available, and anyone who waits for the ideal PCI soundcard to be released will probably still be waiting when the rest of us are releasing our tenth album.

Getting Converted

Metalithic Digital Wings for Audio.

Metalithic Digital Wings for Audio.

Some soundcards have converters (the bits of electronics that turn analogue signals into a stream of digital numbers, and back again) with more than 16 bits. Although there are a few cards and applications that allow recording at 20‑ or 24‑bit resolution (which will give better audio quality), recording at bit depths greater than 16 is not an option in most cases. Even if it was, both 20‑ and 24‑bit recordings take up 50% more hard disk space than 16‑bit recordings, since 16 bits fit neatly into two 8‑bit bytes of memory, but both 20 bits and 24 bits need three 8‑bit bytes of memory to store each sampled point on the waveform.

The point of having 18‑ or 20‑bit converters, even when only recording or playing back a 16‑bit signal, is that they yield better resolution with quiet signals, and can give significantly lower background noise levels. When signal levels are low, the 16th bit ends up flapping on and off in time with the music, and this can give a gritty sounding background quality — a lack of transparency — especially when listening to quieter acoustic recordings. One answer to this problem is to digitally record with more than 16 bits, and then use techniques such as hardware dithering or noise‑shaped dither. Dither adds tiny amounts of continuous noise, so that the signal can gracefully fade away to silence behind the noise, rather than dropping from the 16th bit to nothing, and noise‑shaped dither improves on this basic technique by EQing the noise, so that most of it is at high frequencies that the human ear doesn't notice as much. The result is a 16‑bit signal with clearer sound. So having 20‑bit converters doesn't add bits to the recorded sound, but it does ensure that the maximum amount of audio detail gets onto your digital recordings, and off again. Of course, simply having more than 16 bits in the converters does not guarantee a good soundcard, but it's a worthwhile step in the right direction.

ISA soundcards can cope with multi‑channel data, but PCI can move this data at a much faster rate.

Losing A Bit In The Translation

Once you have these high‑quality signals safely stored on your hard disk, it seems silly to master them by converting back to analogue, passing them through a mixing desk, and then recording them onto a DAT machine via a further set of A/D converters. If your ultimate goal is a DAT tape, DCC, or MD, the answer is to look for a soundcard that provides a digital output, and these can now be found even on budget models. The consumer standard is S/PDIF (Sony/Philips Digital InterFace), and two types are available. The more common is coaxial (also known as electrical) and this uses phono sockets. Although many people use a common‑or‑garden audio phono lead to connect soundcard digital outputs to DAT, this can cause problems (especially with longer cables), as a 75Ω cable should really be used. Audio cables give mismatching problems, because the digital signal reflects back from the far end of the cable, and this can cause errors. Fortunately, this doesn't mean buying expensive, exotic cables of the hi‑fi variety, as 75Ω is the same standard used for video, and even Tandy have 75Ω video cable available for a few pounds.

The other consumer choice for digital I/O is optical (also known as Toslink — from Toshiba) and this uses fibre‑optic cable, which makes light work of the signals (ho ho). If you're buying a soundcard and intend to use its digital facilities, do check that the sockets are the same as those on the equipment you wish to connect it to — you cannot convert between electrical and optical by using a cable with a different plug at each end (you need a converter box costing £50 or more).

Professional equipment features AES/EBU interfacing, which is a 110Ω standard using XLR plugs and sockets. You won't see any of these on the sort of stereo soundcards we're covering this month, but they will certainly put in an appearance in next month's exciting multi‑channel instalment. For this reason, we'll leave TDIF and ADAT interfaces till then, as these are both for multi‑channel use as well.

Get Your Credit Cards Ready

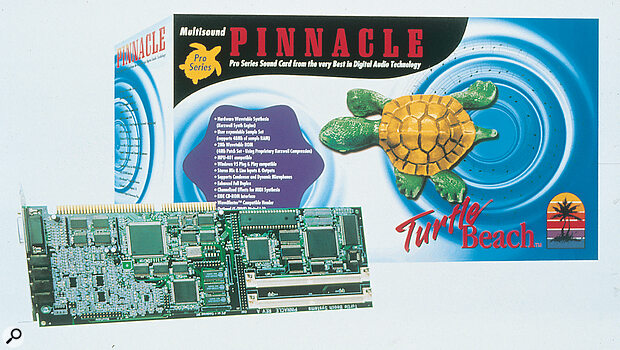

Now that you know about stereo and multi‑channel, ISA and PCI, the differences between converters, and the potential problems with drivers, it's time to narrow things down. Look at the facilities provided by each model in the accompanying table, as well as the more detailed reviews already published in SOS for certain of them. Many have family characteristics — for instance, the Turtle Beach Pinnacle is essentially the Fiji with extra features, and the AWE64 Gold is a more refined version of the AWE64 Value model. As far as noise goes, converters with more than 16 bits tend to be quieter, and the more you pay, the more features and higher audio quality you can expect (in general)!

First, decide just how many input and output channels you need, bearing in mind that it's easier to buy more than you need at the start than to attempt to add more soundcards later. Next, look at the extras — do you need synth facilities, or do you already have external MIDI synths? It's always useful to have a General MIDI synth inside your PC for general‑purpose use when playing back other people's MIDI files, but if the soundcard has a daughterboard socket you can add any Waveblaster synth later with no problems. If you have several MIDI synths, you may want more than one external MIDI output on the soundcard, although a single MIDI input should suffice for most people. If you need sampling facilities on‑board, make sure there's provision for adding more sample RAM (nearly all cards allow this). Here, PCI cards such as the Turtle Beach Daytona have another advantage, since they can use system RAM in this capacity. If effects such as reverb, chorus or surround sound are provided, some cards only let you add these to the on‑board synth, and others may let your sampled sounds access these as well. By now you should have narrowed your choices down to maybe two or three models. Your final choice may be determined by the bundled software — although this is seen by many people as 'free', a wise choice of card can save you several hundred pounds if it includes the sequencer that you were thinking of buying anyway.

Driving You Mad

Nearly all soundcards come complete with a comprehensive suite of software, ranging from full‑blown hard disk recording packages to the latest joystick‑controlled journey into another world (more commonly known as a game). However, the most important item of software is the soundcard driver, since it is this which interfaces between the hardware (the soundcard) and the operating system (Windows 95). Without this, you will not be able to use your soundcard at all. PCI cards can normally be used with both Macs and PCs, and many cards are initially released only with drivers for one or the other, but rarely both. If you're buying a PCI soundcard, make sure that the drivers exist for your computer platform before getting your credit card out.

For PC applications, the most usual type of driver is known as a Windows MultiMedia or WAV driver. This interfaces directly to the Windows 95 Multimedia system, and this is all that stereo cards need. If there are more than two channels available, a fudge is used, with each two channels appearing as a separate stereo pair — so, for instance, an 8‑channel device will appear to Windows as four distinct stereo ones (more about this next month). Many cards now come with DirectX drivers, and these bypass the Multimedia layer to interface with Windows 95 at a lower level. DirectX was written by Microsoft to provide fast mixing of multiple channels of sound to a single stereo output, and they also minimise the delay between recording a sound and hearing it played back (known as latency). Once in place, they are transparent to the user. Incidentally, DirectX drivers are not the same as DirectX plug‑ins, which use the DMSS (DirectX Media Streaming Services) standard to allow real‑time streaming of audio, although they both use similar technology.

Separate drivers should be provided for other features on the card, such as MIDI interfaces, onboard synths, extra sampling synths, and so on (but it is not unknown for initial shipments to go out before these other drivers have been finished). Some special features may have specific PC requirements. For instance, Creative Lab's Waveguide synth is created entirely in software, but needs a true Intel Pentium CPU to carry out all the maths involved (IBM/Cyrix processor chips will not work).

The multiplicity of separate drivers (and the suite of small utility programs normally provided to set them all up) can be initially confusing, but writing a properly integrated driver set not only takes a lot longer but is also far more difficult to update — keeping the drivers separate allows manufacturers to provide bug fixes, in the form of small files which can easily be downloaded via the Internet, more rapidly. Bear in mind that soundcards with a huge array of different features may sometimes prove more difficult to install initially, simply because they need more of your computer's resources. It's worth pointing out that the famed Turtle Beach Fiji and Pinnacle cards, as well as initial shipments of the long‑awaited Terratech EWS64 XL, had teething troubles and caused some people difficulties during installation. These problems have now been resolved, and installation is claimed to be "a breeze" with the latest drivers.

Another point to watch out for is onboard MIDI features that hijack the external MIDI output. Some daughterboard sockets (for adding complete wavetable synths, such as the classic Yamaha DB50XG) are wired to the same MIDI lines as the sockets used to attach other external MIDI devices. If this is the case, every time you play back a sound on an external synth, the daughterboard synth will play a note as well. If you can disable individual MIDI channels on both devices you can work around this, but it can cause a lot of head scratching.

Finally, try to cater for the future. Some cards offer the carrot of letting you add another card at a later date, to provide more channels and facilities. If your PC has the space for this, look for drivers that promise synchronisation for multiple cards, since otherwise you will have problems with sampled sounds played back by different cards gradually drifting out of sync with each other. Normally, if you have two cards from the same manufacturer the problems won't be as bad, but having the facility to lock multiple cards together is a far better option.

Comments

- General: Some synths also include an on‑board synth (generally using the Yamaha OPL3 chip, which has 20 voices). This can be used for games, but has been omitted from the main table since its quality is not suitable for serious music work.

- Creative Labs AWE64: Implements full‑duplex operation with software drivers.

- Maxisound Home Studio 64: Also features 4‑track WAV playback (8 tracks with minimum 4Mb RAM added) with any Windows application.

- Mediatrix Audiotrix 3D‑XG: Uses its daughterboard socket to house the supplied Yamaha DB50XG card.

- Metalithic Digital Wings: Special hardware allows supplied software to play back up to 128 tracks of audio. Synth is promised as future software

- Terratec EWS64 XL: Features a 64‑voice sampler using up to 64Mb RAM, 24dB/octave filters, three EGs and two LFOs.

- Turtle Beach Daytona PCI: DLS (Downloadable wavetable synth) uses up to 10Mb of PC system RAM.

- Turtle Beach Fiji and Pinnacle: Digital card can be added later, but it is cheaper to buy this with the soundcard itself (prices as shown).

- Turtle Beach Pinnacle Project Studio: Daughterboard socket is already used by second supplied Kurzweil synth, and this gives a total of 64 notes and 32‑channel multitimbrality (32 notes and 16 multitimbral channels for each synth).

Contacts

Creative Labs,

Unit 2, The Pavilions, Ruscombe Business Park, Ruscombe RG10 9NN.

Tel: 01245 265265.

Fax: 01734 828270.

Metalithic,

Serious Audio Ltd, 96B Queens Road, Watford, Hertfordshire WD1 2NX.

Tel: 01923 442121.

Fax 01923 442441.

Turtle Beach,

Et Cetera,Valley House, 2 Bradwood Court, St. Crispin Way,Haslingden, Lancs BB4 4PW.

Tel: 01706 228039.

Fax: 01706 222989.

Digidesign,

Avid Technology, Westside Complex, Pinewood Studios, Iver Heath, Pinewood, Bucks SL0 0NH.

Tel: 01753 653322.

Fax: 01753 654999.

Maxisound,

Ubi Soft Ltd, Bridge House, 11 Creek Road, Hampton Court,Surrey KT8 9BE.

Tel: 0181 944 9000.

Fax: 0181 944 9300.

Mediatrix,

RKMS, Freepost (NG6175), Nottingham NG4 1BR.

Tel: 0116 961 1398.

Fax: 0115 953 3802.

Midiman,

Midiman UK

Tel: 01205 290680.

Fax: 01205 290671.

Terratec,

Time & Space, PO Box 4, Okehampton, Devon EX20 2YL.

Tel: 01837 841100.

Fax: 01837 840080.