Art Of Moog perform at Kings Place, London, for the 2018 Bach Weekend.Photo: Robin Bigwood except where indicated

Art Of Moog perform at Kings Place, London, for the 2018 Bach Weekend.Photo: Robin Bigwood except where indicated

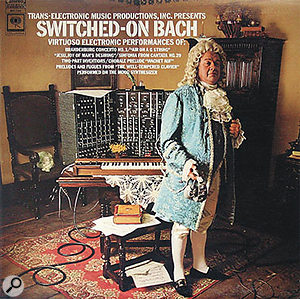

To mark its 50th anniversary, two bands have taken to the stage to pay homage to Wendy Carlos’s classic crossover album Switched-On Bach.

2018 marks the 50th anniversary of one of the most iconic, groundbreaking and well-loved electronic music albums of all time: Wendy Carlos’s Switched-On Bach. Still a benchmark now, in 1968 it arrived as a tour de force demonstration of the new Moog modular synth, and spawned countless gimmicky ‘switched-on’ rip-offs in the following years. Wendy Carlos, a serious composer as well as synth pioneer, went on to score various films (not least Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange and Disney’s Tron) and develop her own material too.

A defining feature of Switched-On Bach is its studio-album status. The performances were put together painstakingly, with monophonic lines multitracked to eight-track tape over a period of weeks or months, and the kaleidoscopic electronic timbres generated in response to careful segmenting of Bach’s interweaving musical lines. Analogue modular synths don’t typically lend themselves to fast, agile recall of patches, so a Switched-On Bach Live was never likely to happen; at least not until some time into the ’80s — by which point, ironically, enthusiasm for those glorious creamy Moog tones had waned in favour of digital synthesis techniques and sampling. It’s also telling that other classical crossovers of the same era that did happen live — like Emerson, Lake and Palmer’s Pictures At An Exhibition — were never purely synth-based. Modular and Minimoogs might have been there on stage, but the sound was often rooted in traditional orchestral or rock line-ups.

A defining feature of Switched-On Bach is its studio-album status. The performances were put together painstakingly, with monophonic lines multitracked to eight-track tape over a period of weeks or months, and the kaleidoscopic electronic timbres generated in response to careful segmenting of Bach’s interweaving musical lines. Analogue modular synths don’t typically lend themselves to fast, agile recall of patches, so a Switched-On Bach Live was never likely to happen; at least not until some time into the ’80s — by which point, ironically, enthusiasm for those glorious creamy Moog tones had waned in favour of digital synthesis techniques and sampling. It’s also telling that other classical crossovers of the same era that did happen live — like Emerson, Lake and Palmer’s Pictures At An Exhibition — were never purely synth-based. Modular and Minimoogs might have been there on stage, but the sound was often rooted in traditional orchestral or rock line-ups.

Fast forward to the present, and once again analogue and modular are ‘in’. Demand for vintage gear has never been so high, the modular market is a veritable smorgasbord of tasty options, and the new breed of integrated synths stay in tune and have plenty of patch memories.

All of which leads nicely to the main gist of this article, about how two UK-based groups — Art Of Moog and the Will Gregory Moog Ensemble (see box) — are essentially recreating the spirit of Switched-On Bach live on stage. The approaches are very different, in terms of line-up, gear, arrangements and live sound practice, but both have garnered a following of synth nerds, Bach buffs and old hippies alike.

Art Of Moog

Art Of Moog are my own group, and more than anything here I wanted to go into some detail about how we went from first concept to live performance in a relatively short space of time. Many readers, whether performing artists, composers, arrangers and producers, will no doubt recognise some of the same challenges and pressures.

The author, and Art Of Moog director, Robin Bigwood.Like many good things, Art Of Moog were dreamt up in the pub. It was the end of 2016, after a gig, and I was with a musician friend who curates an annual festival at London’s Kings Place, dedicated to the music of German baroque composer Johann Sebastian Bach. He needed to fill concert slots in the 2018 festival, the anniversary of Switched-On Bach was just begging for some kind of acknowledgment, and it seemed like a fun project. Within a couple of weeks a performance date had been agreed, and all of a sudden Art Of Moog had just less than 18 months to amass personnel, gear and musical material before they’d be on stage in front of a paying audience. One of those moments when you suddenly realise what you’ve taken on...

The author, and Art Of Moog director, Robin Bigwood.Like many good things, Art Of Moog were dreamt up in the pub. It was the end of 2016, after a gig, and I was with a musician friend who curates an annual festival at London’s Kings Place, dedicated to the music of German baroque composer Johann Sebastian Bach. He needed to fill concert slots in the 2018 festival, the anniversary of Switched-On Bach was just begging for some kind of acknowledgment, and it seemed like a fun project. Within a couple of weeks a performance date had been agreed, and all of a sudden Art Of Moog had just less than 18 months to amass personnel, gear and musical material before they’d be on stage in front of a paying audience. One of those moments when you suddenly realise what you’ve taken on...

What exactly is involved in getting this kind of project off the ground? A lot more work, and outlay, than I was initially expecting, it turns out.

People & Purchases

Our first thoughts about Art Of Moog’s line-up were to have three players, and — in contrast to the 2015 Bach To Moog album by Craig Leon, which blended synths with acoustic strings — only synths. And then perhaps only Moogs, in a conspicuous nod towards Switched-On Bach. To get the ball rolling I bought one of the well-known Sub 37s (having been looking for an excuse for years). Then perhaps we’d beg or borrow additional Sub 37s (or perhaps Minimoog Voyagers) for the other musicians, and I’d supplement them with Arturia’s Modular-V and XILS Labs’ PolyM virtual synths running in Apple MainStage, for chordal/polyphonic duties.

It was an idea that sounded great in principle, but in reality, it was a little naïve. It’d certainly be possible to adapt a fair number of pieces by Bach for three monosynths, but with so few players, everyone would need to play polyphonically, really, to tackle the bigger and more interesting pieces in the repertoire. And if each part were multitimbral too, that could add a lot of colour and contrast. At the same time, a week of experiments and testing with MainStage were almost comically unsuccessful. PolyM sounded lovely but crashed it, Modular-V often ate up too many processor cycles, and the final nail in the coffin was a motherboard failure of the year-old MacBook Pro it was running on. All computer-based efforts felt worryingly unreliable, so hardware seemed the only way forward.

However, aside from the inevitable financial investment required, finding polysynths with the right kind of sound quality, reliability and flexibility wasn’t easy. Over a period of months I tried out and subsequently re-sold a succession of (mostly virtual analogue) polys: Korg Radias and King Korg, Studiologic Sledge, an old Novation KS, Waldorf Streichfett and DSI Prophet Rev 2. All had plus points but didn’t quite cut the mustard in one way or another.

The first encounter with a Nord Lead A1 was a turnaround, though. Aside from being able to churn out an endless stream of great (and surprisingly old-fashioned-sounding) patches, its four-synths-in-parallel architecture lends itself to creating layered sounds consisting of wildly different timbres — a real signature technique of Wendy Carlos. The Nord’s parameter morph feature also allows an expression pedal to fade between two wildly different-sounding states of the synth. We could use that to alternate pairs of patches, or smoothly dial in many simultaneous parameter changes. Different sounds (and morphs) could be set up on either side of a keyboard split, too — and all without the player taking either hand from the keyboard. We ended up with no fewer than three Lead A1s: one per player. Or, to be specific, two of the now-discontinued A1R modules, bought very cheaply second hand, plus an A1 keyboard. The modules were played from Nektar Panorama P6 and Novation SL61 MIDI controllers.

The on-stage nerve-centre of the project, effectively. Moog, Nord and Oberheim synths with Behringer mixer, Electro-Harmonix vocoder and Zoom multi-effects unit. Multiple expression pedals were used to control the synths while leaving hands free to play.Photo: Robin Bigwood

The on-stage nerve-centre of the project, effectively. Moog, Nord and Oberheim synths with Behringer mixer, Electro-Harmonix vocoder and Zoom multi-effects unit. Multiple expression pedals were used to control the synths while leaving hands free to play.Photo: Robin Bigwood

For my own synth setup, I still had the Sub 37 as well as a Nord, and in an eye-watering credit-card manoeuvre, finally added an Oberheim OB-6 for various silky pad and lead duties. I also acquired an Electro-Harmonix V256 vocoder, to allow me to perform some vocal numbers without it sounding like a dying buffalo was at the mic, and a DigiTech JamMan Solo XT as a playback device for a few extra-musical elements and sound effects.

Annabel Knight with her Akai EWI5000 driving the diminutive but powerful Roland SE-02, mounted on a shelf on the music stand.Photo: Robin BigwoodThe gear was all starting to look promising, and got even more so when one final element was added: a wind synth. As they neared completion, a few musical arrangements cried out for one additional instrumental line: sometimes to make them a little less fiendish to play on keyboard, but more to add a unique colour and expressive character. So flautist Annabel Knight joined the group, playing a Roland/Studio Electronics SE-02 analogue monosynth from an Akai EWI5000 (used purely as a controller). The Roland’s decent MIDI spec, in contrast with that of Behringer’s Model D, for example, allowed it to work really well with the Akai, and injected a swathe of vibrant Minimoog-esque tones without requiring anyone to bankrupt themselves getting the real thing.

Annabel Knight with her Akai EWI5000 driving the diminutive but powerful Roland SE-02, mounted on a shelf on the music stand.Photo: Robin BigwoodThe gear was all starting to look promising, and got even more so when one final element was added: a wind synth. As they neared completion, a few musical arrangements cried out for one additional instrumental line: sometimes to make them a little less fiendish to play on keyboard, but more to add a unique colour and expressive character. So flautist Annabel Knight joined the group, playing a Roland/Studio Electronics SE-02 analogue monosynth from an Akai EWI5000 (used purely as a controller). The Roland’s decent MIDI spec, in contrast with that of Behringer’s Model D, for example, allowed it to work really well with the Akai, and injected a swathe of vibrant Minimoog-esque tones without requiring anyone to bankrupt themselves getting the real thing.

The Music

Personnel and gear were one thing; musical material was quite another. What to play had to be decided, and then arrangements made to shoehorn it into the four-player line-up, with appropriate sounds: a fascinating process which took months and months of hard work.

Actually, the ‘what’ question wasn’t too difficult. To maintain interest across the musical set, it made most sense to tackle attractive (and often well-known) individual movements rather than complete multi-movement works. Added to that, I’d always wanted to include one piece (Sinfonia to Cantata no. 29) as an obvious Switched-On Bach tribute, with similar sounds. After that, it was a case of choosing specific pieces that would work well for the line-up, balance within a longer programme, and appeal to listeners.

Art Of Moog member Martin Perkins, in rehearsal with one of the Nord Lead A1s that were so well suited to the project. The three-manual practice organ in the background was not used...Photo: Robin BigwoodThe ‘how’ was more challenging. With six hands plus wind-synth, Art Of Moog have the potential to generate seven concurrent musical lines at any one time, or thereabouts. Some pieces in JS Bach’s massive compositional output call for more than that, or have instrumental ranges that don’t quite suit the synths’ keyboard compasses. However, to some extent that can be sidestepped with polyphonic playing, layering sounds for unison or octave textures, and making the odd octave transposition mid-piece. The goal was always to play the repertoire stylishly (and in a way that an 18th Century listener might actually approve of), but we weren’t bound to the same strictures normally faced when performing this music on acoustic instruments to purist classical audiences. Tastes in that area can be conservative and traditional; we knew we’d already be offending some listeners anyway, just through the involvement of electronics, so pleasing all the people all the time was never a priority. In general, too, the less we worried about historical correctness the more successful the arrangements seemed to become.

Art Of Moog member Martin Perkins, in rehearsal with one of the Nord Lead A1s that were so well suited to the project. The three-manual practice organ in the background was not used...Photo: Robin BigwoodThe ‘how’ was more challenging. With six hands plus wind-synth, Art Of Moog have the potential to generate seven concurrent musical lines at any one time, or thereabouts. Some pieces in JS Bach’s massive compositional output call for more than that, or have instrumental ranges that don’t quite suit the synths’ keyboard compasses. However, to some extent that can be sidestepped with polyphonic playing, layering sounds for unison or octave textures, and making the odd octave transposition mid-piece. The goal was always to play the repertoire stylishly (and in a way that an 18th Century listener might actually approve of), but we weren’t bound to the same strictures normally faced when performing this music on acoustic instruments to purist classical audiences. Tastes in that area can be conservative and traditional; we knew we’d already be offending some listeners anyway, just through the involvement of electronics, so pleasing all the people all the time was never a priority. In general, too, the less we worried about historical correctness the more successful the arrangements seemed to become.

Still, the process took a long time, and passed through distinct phases: locating the original musical score, copying it into a notation application (we used Sibelius), redistributing the material to suit synth and polyphony capabilities, and developing synth patches for the resulting parts. The original Switched-On Bach sounds were an influence here, but weren’t a limiting factor. Arguably, we had a much bigger palette than Wendy Carlos anyway, and it was more interesting to bring in some of the particular capabilites of our instruments.

I’ve already mentioned the Nord A1’s sophisticated layering and morphing abilities: these proved themselves time and time again. Meanwhile, the Akai/Roland wind-synth pairing really lent itself to the most expressive, sinuous lines, and had a dynamic range and agility that would have been difficult to match from a keyboard controller. In essence, the dynamic shape of every note is controlled by breath pressure, not envelope shape: Annabel Knight could fade notes from and to zero, as it were, in a way that’s impossible with a conventional keyboard controller.

All the synths had arpeggiators, and they got used quite a bit. The familiar rippling broken chord effect could mirror Bach’s lute/guitar-style writing for harpsichord, but unpitched or ring-modulated random patterns were also the basis for some rhythmic backdrops. There were also several ‘sparkling’ pads consisting of arpeggiated notes blended to something more nebulous, with added delay and reverb.

Finally, the Electo-Harmonix V256 vocoder has an internal MIDI-driven carrier synth, so its operation can be more self-contained than that of many other vocoders. It sounds very contemporary and clear, too; but we also used a more conventional audio routing, with a modulator signal from a vocal mic and carrier from the Roland SE-02. Having two different musicians responsible for the vocoded components was a deliberate ploy: there was a certain looseness in the effect that reeked of vintage.

Performance

With extremely limited time available for the stage setup, each individual synth station had been pre-prepared as much as possible, and its position on the stage ‘spiked’ with adhesive tape (visible next to the stands on the left).Photo: Robin BigwoodThere’s nothing like the deadline of a public concert to focus a performer’s preparation, and for Art Of Moog, that extended to the technical setup just as much as the musical performances.

With extremely limited time available for the stage setup, each individual synth station had been pre-prepared as much as possible, and its position on the stage ‘spiked’ with adhesive tape (visible next to the stands on the left).Photo: Robin BigwoodThere’s nothing like the deadline of a public concert to focus a performer’s preparation, and for Art Of Moog, that extended to the technical setup just as much as the musical performances.

Although we’d got the chance to soundcheck in Hall One at Kings Place a couple of days before the performance, the setup on the day was a challenge. For our late-night slot we had a frankly terrifying one hour to get all the synths on the stage, plugged in and working after the stage had been cleared from a previous orchestral concert. Because of the potential for things to go catastrophically wrong here, we’d considered very carefully in advance how to do the manoeuvre under pressure. Cables, stands and power supplies were pre-allocated for each synth-player’s spot on stage, synths were unpacked ahead of time, and an on-stage mixer was marked up to show exactly what input went where, and the settings for each channel. Various crib sheets also summarised synth and effect unit patch settings.

Modestly capable: the on-stage Behringer QX1832USB mixer.Photo: Robin BigwoodThe decision to submix all the synths on stage, and only feed a single stereo output to the venue PA, had also been considered carefully. It made the setup much more self-contained, and removed the need to have a balance engineer familiar with the material following the scores. There had neither been time nor budget to do otherwise.

Modestly capable: the on-stage Behringer QX1832USB mixer.Photo: Robin BigwoodThe decision to submix all the synths on stage, and only feed a single stereo output to the venue PA, had also been considered carefully. It made the setup much more self-contained, and removed the need to have a balance engineer familiar with the material following the scores. There had neither been time nor budget to do otherwise.

The mixing desk was modest — a Behringer QX1832USB — but worked flawlessly. The internal Klark-Teknik effect processor on this model sounds superb: its Plate reverb algorithm was used throughout as a kind of vintage-flavoured ‘glue’. Additional effects came from another modest unit, a Zoom MS-70CDR multi-effects pedal, patched into one of the Behringer’s auxes. That provided delays, some stereo panning, and ‘ice’ style reverbs in the manner of the Strymon Big Sky.

Kings Place’s Digidesign D-Show console.Photo: Robin BigwoodKings Place itself has a superb acoustic and PA spec. The 420-seat Hall One is a purpose-built ‘building within a building’ design by Arup Acoustics: essentially a huge box resting on rubber springs, isolated from the outside world. Much of the interior surface is in oak veneer — over an acre of it, originating from a single tree. For Art Of Moog, the hall was put into an acoustically dampened state, by bringing into play a huge 6x60m motorised curtain that runs in a space behind structural pillars. Front-of-house speakers are all by d&b — arrays of Q7 and E8 cabinets, with E15 and B2 subwoofers. They’re part of a multi-channel system co-ordinated with a 48+16-channel Digidesign D-Show console. It, along with sound engineer Carlos Boix, weren’t over-taxed by Art Of Moog’s single stereo feed from the stage, but the resulting sound was phenomenally good: more like a top-class studio monitor system than the sort of bass-heavy thump of lesser venues. Slick lighting design by Kings Place’s Andy Watson also made a huge impact on the atmosphere of the gig.

Kings Place’s Digidesign D-Show console.Photo: Robin BigwoodKings Place itself has a superb acoustic and PA spec. The 420-seat Hall One is a purpose-built ‘building within a building’ design by Arup Acoustics: essentially a huge box resting on rubber springs, isolated from the outside world. Much of the interior surface is in oak veneer — over an acre of it, originating from a single tree. For Art Of Moog, the hall was put into an acoustically dampened state, by bringing into play a huge 6x60m motorised curtain that runs in a space behind structural pillars. Front-of-house speakers are all by d&b — arrays of Q7 and E8 cabinets, with E15 and B2 subwoofers. They’re part of a multi-channel system co-ordinated with a 48+16-channel Digidesign D-Show console. It, along with sound engineer Carlos Boix, weren’t over-taxed by Art Of Moog’s single stereo feed from the stage, but the resulting sound was phenomenally good: more like a top-class studio monitor system than the sort of bass-heavy thump of lesser venues. Slick lighting design by Kings Place’s Andy Watson also made a huge impact on the atmosphere of the gig.

In the end, Art Of Moog’s King’s Place debut went beautifully — no technical hitches, and the analogue synths remained perfectly in tune with the virtual analogues. One of the advantages of modern tech... It was fascinating to speak to many audience members afterwards, and to realise what a wide range of musical backgrounds and interests they represented. Classical, jazz, rock and electronica camps were all there, and unified on that one evening, I think, by a shared appreciation of the quality and universality of Bach’s music most of all, as much as for the genre-fluid nonconformist nature of the whole thing.

From the band’s point of view, the overwhelming impression was of how deeply rewarding and liberating it all felt. Not because it was any easier to pull off than a normal classical concert, but because it’s largely outside of any established tradition. We knew anything we did would more likely be judged on its own terms, rather than according to any arbitrary or old-fashioned standards.

Art Of Moog is still at the beginning of its journey, but it’s one that has been tremendously enjoyable so far, and promises a lot for the future. After all, there’s over 1100 pieces in Bach’s catalogue of works...

Fugue State

In case you were wondering, Art Of Moog’s name is a mild pun on one of Bach’s later and most complex works: the Art Of Fugue. It works best if you use the cow-related pronunciation of Moog — to which, luckily, Bob Moog didn’t seem to object.

Ivory Tower

Harpsichordist Steven Devine.Photo: Robin BigwoodFinding keyboard players to complete the Art Of Moog line-up could have been a real problem: they had to be classically trained people who could reliably perform challenging two-hand, multi-voice contrapuntal writing, and learn it quickly, but who weren’t fazed by the technology or sniffy about the whole concept. In the end it was two fellow harpsichordists who stepped up to the mark: Steven Devine and Martin Perkins.

Harpsichordist Steven Devine.Photo: Robin BigwoodFinding keyboard players to complete the Art Of Moog line-up could have been a real problem: they had to be classically trained people who could reliably perform challenging two-hand, multi-voice contrapuntal writing, and learn it quickly, but who weren’t fazed by the technology or sniffy about the whole concept. In the end it was two fellow harpsichordists who stepped up to the mark: Steven Devine and Martin Perkins.

Harpsichordists were always the obvious candidates for the job, and not just because they tend to be Bach obsessives. As a musical breed they’re also often very adaptable: to differing instrument designs and key actions just as much as getting a handle on wildly differing playing styles (and, scarily often, incomplete musical scores). Whilst these two’s exposure to synths had so far been fairly limited, they were both tech-savvy and had plenty of experience of audio recording, on both sides of the mic. Coincidentally, too, they’ve both been involved in producing commercial Kontakt sample libraries: Steven had worked with Spitfire Audio on Steven Devine — Harpsichord (still one of the best on the market), and Martin Perkins on SonicCouture’s interesting historically oriented The Conservatoire Collection.

Annabel Knight’s background was as a flautist and recorder player, and although Art Of Moog was her first outing on the EWI she also mastered it very quickly. Having played on many film soundtracks (not least some of the Harry Potter series), at Abbey Road and other high-profile studios, she was all too familiar with working in a time-pressured and technology-rich environment.

Will Gregory’s Moog Ensemble

Will Gregory.Photo: Serge LeblancWill Gregory is probably best known to SOS readers as one half of the electronic pop duo Goldfrapp. He’s a remarkably versatile musician who studied classical music at York university and has since played with Tears For Fears, Peter Gabriel, the Cure and Portishead. He’s also played sax with London Sinfonietta, written an opera, and directs the Will Gregory Moog Ensemble — another Bach on synths outfit.

Will Gregory.Photo: Serge LeblancWill Gregory is probably best known to SOS readers as one half of the electronic pop duo Goldfrapp. He’s a remarkably versatile musician who studied classical music at York university and has since played with Tears For Fears, Peter Gabriel, the Cure and Portishead. He’s also played sax with London Sinfonietta, written an opera, and directs the Will Gregory Moog Ensemble — another Bach on synths outfit.

The ensemble was founded in 2005 for a performance at the Bath Festival. The idea of a Wendy Carlos-style recreation had been suggested to Will by the festival’s director, and got an enthusiastic response. Like many synth aficionados in the ’70s and ’80s he had been heavily influenced by Switched-On Bach and Wendy Carlos’s later albums too, and was apparently all too pleased to share out his collection of analogue monosynths (some of which were only getting used “about once a year”, he told me) amongst a group of willing participants. The first outing had nine players, to cover the nine parts of Bach’s well-known 3rd Brandenburg Concerto, which had been a centrepiece of Switched-On Bach. Since then the ensemble has worked, at different times, with more and fewer players too.

Will Gregory Moog Ensemble at LSO St Luke’s in London, May 2018.Photo: Robin Bigwood

Will Gregory Moog Ensemble at LSO St Luke’s in London, May 2018.Photo: Robin Bigwood

I spoke to Will after a Moog Ensemble concert this year at LSO St Luke’s church in London: part of the Barbican Centre’s Sounds & Visions festival curated by Max Richter. He explained a bit more about the group’s philosophy.

“Wendy Carlos’ task was to showcase the muscularity of the Moog. We’re trying to showcase the performance aspects of these synths, sculpting and shaping as we go.” Interestingly, not everyone in the group is a specialist keyboard player, with a background in creating sounds. “Some people are less familiar with analogue synths than they are with pianos, or harps for example, and need a little bit more guidance [with patch programming].”

It’s also notable that Will Gregory himself played most of the London gig with a Yamaha WX7 wind controller driving a vintage Minimoog. Two other band members went a similar route, playing a Roland ProMars MRS-2 from a Yamaha WX11, and a Moog Sub 37 from an Akai EWI5000. However, plenty of other interesting analogue synths were being played in a conventional fashion: not least three more Minimoogs, a Multimoog, another Sub 37, a Model 15 modular, plus Roland SH-09, SH-101 and Korg 700s. Perhaps the ensemble’s rarest instrument, albeit not used in London, is a DK Synergy II: a digital additive synth that was championed by Wendy Carlos (see ‘Beyond The Moog’ box).

A notable feature of the Will Gregory Moog Ensemble is their use of individual amps for each player. The idea, Will told me, is to recreate the experience, familiar to any acoustic instrument or orchestral player, of each musician being responsible for his or her own level within an ensemble. And while venue PA and foldback is used, it’s often just adding a sense of scale or ambience. It’s still the on-stage amps that account for the greater part of the ensemble’s sound. “We certainly considered the amps according to each musician’s role. So there’s an Ampeg bass amp for the bass lines. But we also use amps for character, and to add more bite to leads, for example. There’s a Vortexion valve amp, a Fender guitar amp, and Ruth [Wall] was using a small Trace Elliot amp with the Korg 700, even though it might not sound so nice really, to give it a more strident quality. Everybody takes personal responsibility for their level, and not always with the volume knob. You can also use the synth’s filter to roll off the top end, and become quieter that way. The feed to the venue PA is from the amps, so the sound engineer has to be ready to handle some big changes in level!”

Nestling in with the vintage synths and character amps are some surprisingly modest effects units. “I bought a lot of second-hand Alesis reverbs: Midiverbs, Midiverb 2s, 3s, 4s, Quadraverbs. I really like the sound of those early digital reverbs. Ade [Adrian Utley, of Portishead et al] might bring something more bespoke, perhaps a spring reverb, or an Eventide.”

There’s more details about the ensemble, and forthcoming tour dates, at willgregorymoogensemble.co.uk.

Wendy Carlos: Beyond The Moog

If you’re a Moog or modular devotee and you don’t know Switched-On Bach... well, you really should. Carlos had an incredibly close working relationship with Bob Moog (she says they’d been friends for 41 years when he died in 2005) and was instrumental in the development of several of his modules, vocoder designs, and keyboard touch-sensitivity. Switched-On Bach is surely one of the most indulgent celebrations of the Moog sound ever conceived, and for an album from the late ’60s the sound quality and breadth of timbres on offer is pretty magical.

What many find intriguing, though, is how by the 1980s Carlos had largely turned her back on the Moog, and analogue synthesis in general. Many later photos show her seated with distinctly un-analogue synths, with not a patch lead in sight.

She embraced digital synthesis as soon as it became practically viable, albeit using several Digital Keyboards Synergy and Crumar GDS additive synths rather than the usual suspects of DX7, Fairlight and Synclavier, from the same era. For analogue die-hards, the sound of these machines, and the 1987 Secrets Of Synthesis album in which Carlos espouses them, can be a tough listen. Her own contention, by then, was that analogue’s limitations were too frustrating, and the subtractive synthesis paradigm too ‘thick’ sounding and limited in scope to be worthy of continued exploration. What the additive synths offered was far greater control of harmonic content over time, which could be directed towards more realistic impersonations of acoustic instruments, hybrid timbres (bowed pianos, plucked oboes and so on), and novel inharmonic sounds. They also allowed for microtonal tuning, which was an important personal interest for Carlos. Development of her studio continued on with the addition of various Kurzweil synths and software sequencers in the early 2000s.

Most synth players today prize knobby analogue (and virtual analogue) machines above nearly all else. They’re responsive, characterful, and often give rise to serendipitous discoveries. 1980s digital synths and ’90s ROMplers, by comparison, can seem sterile and joyless. But it would be too easy to criticise Carlos’s changing preferences without remembering that as well as a synth player she was also a researcher and academic. She’d been on the cutting edge, leveraging the newest technologies, long before most of us had even heard the term ‘synthesizer’. And she remained on it for decades as new technologies came and went, regardless of fashion. That takes real vision, and single-mindedness.