By specialising in programmes for ice dance, Rob Colling has perhaps hit on the most niche career in music!

By specialising in programmes for ice dance, Rob Colling has perhaps hit on the most niche career in music!

With arbitrary tempo restrictions to contend with and Olympic glory riding on every cut, adapting music for ice dance represents a unique editing challenge.

It’s 28 September 2017. The scene: the Nebelhorn Trophy, a high-level international ice skating competition and the qualifying event for the 2018 Winter Olympics. Top British ice dance team Penny Coomes and Nick Buckland have just finished their short dance. It’s the first time they’ve competed internationally since a horrifying fall in mid-2016 smashed Penny’s knee into eight pieces, and commentators had begun to dismiss a comeback as unlikely, but Penny and Nick have just skated the best short dance of their career. They’re about to win the competition by a huge margin and qualify to skate at the Olympics.

In Eastern Finland, a slightly scruffy music editor from Middlesbrough is whooping and hollering, jumping around his living room with his hands in the air.

Freeze frame. Yup, that’s me. You might be wondering what I’m doing in this story. More to the point, you’re probably wondering why an article in Sound On Sound has begun like an unusually sequin-embroidered episode of Quantum Leap. Well, as it happens, the story of Coomes & Buckland’s short dance music is a bit of a time-travelling tale. There will be modular synths and dancing cats, there will be VST plug-ins galore and a makeshift mastering studio in an ice rink. But let’s start by rewinding a few years.

Ancient History

In 1994, a decade after winning Olympic gold with their famous free dance to Ravel’s Bolero, British ice dance legends Jayne Torvill and Christopher Dean returned to the Winter Olympics after many years away from competition. Their rhumba, set to a big-band version of the classic song ‘Historia de un Amor’ re-titled ‘History of Love’, scored higher than any other team’s original dance and stunned fans with its elegance.

In the UK, a slightly scruffy student from Middlesbrough was… well, it would be nice to say I was watching Torvill & Dean on TV, but I was probably jamming with my mates in someone’s garage, with a cider and black balanced on top of my Roland D5.

Penny Coomes and Nick Buckland in action.Photo: Robin RitossSome time later, a girl named Penny Coomes and a boy named Nick Buckland met and began practising ice dance together — at Torvill & Dean’s old home club in Nottingham, as it happens. Further north, I spent many years playing gigs and amassing tatty old synths, then moved to Finland with my family and started a business editing music for ice skaters. And Torvill & Dean’s Rhumba d’Amor acquired a life of its own, becoming one of the repertoire of pattern dances from which the International Skating Union (ISU) picks compulsory elements every year.

Penny Coomes and Nick Buckland in action.Photo: Robin RitossSome time later, a girl named Penny Coomes and a boy named Nick Buckland met and began practising ice dance together — at Torvill & Dean’s old home club in Nottingham, as it happens. Further north, I spent many years playing gigs and amassing tatty old synths, then moved to Finland with my family and started a business editing music for ice skaters. And Torvill & Dean’s Rhumba d’Amor acquired a life of its own, becoming one of the repertoire of pattern dances from which the International Skating Union (ISU) picks compulsory elements every year.

The last stop on our time travels is 2016. Penny and Nick have become the dominant team in British ice dance, placing third in the European Championships and seventh at Worlds. I’ve just started working with them on their 2016/17 Rolling Stones short dance. And then… the brakes slam on. In the aftermath of Penny’s big fall, her knee is full of metalwork, her recovery time is projected to be many months, and her career hangs in the balance.

Sticks & Stones

Ice dancers and figure skaters are made of stern stuff. I’ve edited music for skaters who have broken a toe and not noticed for two days, or who have broken a leg in competition but insisted on finishing their routine before being carted off to hospital! The sparkly stuff is only skin deep; these people are made of steel underneath, and Penny more so than most.

While a heroically determined Penny began literally learning to walk again, Nick and I got to work improving the short dance music. I turned the Rolling Stones programme into a full-throttle mashup while Nick refined the choreography and produced a showstopper. Then came another setback: the metal in Penny’s knee was causing nerve problems and had to be removed, meaning several more months of recovery time. With heavy hearts Nick and Penny decided to abandon the 2016/17 season and get a head start on their 2017/18 programmes instead. The Winter Olympics were looming, and it was time for us all to put our heads together and come up with a new short dance that could compete with the best in the world.

To Penny and Nick, the ISU’s pattern dance choice (see boxout) for 2017/18 seemed like an omen. The chosen dance was, you guessed it, Torvill & Dean’s rhumba. The parallels were uncanny: this was a dance performed by Britain’s top ice dance team, in an Olympic year, in a dramatic comeback after a long time out of competition. Maybe we could look at modernising ‘History Of Love’ for the 2018 short dance?

An excited series of phone calls and emails began between Michigan and Finland. Nick and Penny loved the excitement of figure skating legend Daisuke Takahashi’s 2010 short program, which used the Perez Prado version of ‘Historia de un Amor’ along with DJ Dero’s samba-techno masterpiece ‘Batucada’. A structure like that could work with Torvill & Dean’s ‘History of Love’ in place of Prado’s, we decided. Even Christopher Dean himself agreed to choreograph the program. But there was one hefty spanner in the works: the pattern dance tempo.

Tempo Tantrum

The ISU chooses a set tempo for the pattern dance every year, and every so often they throw a curve ball. A classic ballroom rhumba is at 102-104 bpm, and the tempo of Torvill & Dean’s rhumba was 106bpm. So far, so good. But, after what I can only assume was a hearty lunch of intoxicants, the ISU decided their required tempo for the rhumba would be 172-180 bpm. Whaaat?

I am prepared to try anything once, and so I made a drum & bass version of ‘History Of Love’ as an experimental demo for Nick. However, let us not speak of it again.

The next idea was to count at half speed, giving us a target of 86-90 bpm. That meant dramatically slowing down the Torvill & Dean music, but if I could find a way to do that, we had the germ of a concept. With a slow ‘50s-styled first section containing the pattern dance, a 1994-spec middle section at the original 106bpm, and then a faster ending in the style of Takahashi’s program to bring us up to date, we had a three-act program that would build in excitement and modernise the Torvill & Dean original whilst also being an homage to it. It could be, as it were, the history of ‘History of Love’.

Ice & A Slice Algorithm

Rob's finished arrangement in Ableton Live.I edit all my programme material in Ableton Live, partly because the current pricing structure for Pro Tools doesn’t work for me, but mainly because of Live’s warping abilities. I tried simply slowing down ‘History of Love’ but I wasn’t hopeful. Speeding music up for skating programs can often work, but slowing it down usually sounds like a dog’s dinner. Even with the kind of top-drawer bow-tie-and-tails musicians Torvill & Dean had used, the tiny amounts of ‘groove’ in each player’s performance become whopping great big timing errors when you start slowing things down by 20 percent. But I don’t like to rule ideas out without trying them, so Nick and Penny told me where they wanted to put their pattern dance and I used Ableton’s tap-tempo and warp functions to make that section exactly 89bpm. The result? It sounded as though the orchestra were performing whilst immersed in treacle. Not the lively sound we were looking for!

Rob's finished arrangement in Ableton Live.I edit all my programme material in Ableton Live, partly because the current pricing structure for Pro Tools doesn’t work for me, but mainly because of Live’s warping abilities. I tried simply slowing down ‘History of Love’ but I wasn’t hopeful. Speeding music up for skating programs can often work, but slowing it down usually sounds like a dog’s dinner. Even with the kind of top-drawer bow-tie-and-tails musicians Torvill & Dean had used, the tiny amounts of ‘groove’ in each player’s performance become whopping great big timing errors when you start slowing things down by 20 percent. But I don’t like to rule ideas out without trying them, so Nick and Penny told me where they wanted to put their pattern dance and I used Ableton’s tap-tempo and warp functions to make that section exactly 89bpm. The result? It sounded as though the orchestra were performing whilst immersed in treacle. Not the lively sound we were looking for!

Nick and I talked about the problem by phone from our cars: he’d be heading to the ice rink in Novi, Michigan, where he and Penny train, and I’d be heading to my local ice rink in Joensuu to pick up my daughter, who is a figure skater. Almost daily, we’d drive towards our respective ice rinks, in a kind of synchronised transatlantic car ballet, and talk over our ideas. Could we add extra percussion to pull the music into time? Or sample it and quantise?

In the end, the winning strategy was to rather painstakingly remove instruments using Melodyne and then add new ones. Out went the original bass guitar, piano, drums and some rhythmic brass parts, leaving just the solo trumpet melody, strings, a few brass stabs, and the upper ‘strummy’ frequencies of the acoustic guitar part, which contains the actual rhumba rhythm. In came new cabasa, cymbal and piano parts that I played, along with a programmed conga part copied, I will sheepishly admit, from a YouTube “how to play rhumba” tutorial video! With everything nice and neatly in time at the slower tempo, we had our groove back.

Claves & Cats

Nick and Milo the cat show off their ice dance moves.You may be able to see in the screenshot of the arrangement that there are some extra percussion tracks called ‘cat perc’. Nick wanted to make it crystal clear to judges that he and Penny were hitting the right accents in the pattern dance, so he asked me to add percussion hits on those accented beats. He decided to shoot a quick video showing me which beats to emphasise, but with Penny still unable to walk, let alone dance, a substitute dance partner was needed. Which is how I ended up laughing fit to burst as I watched one of the world’s elite ice dancers in the hallway of his flat, dancing the rhumba with a cat as his dance partner! I have to admit that Milo the cat is a pretty nifty mover, actually.

Nick and Milo the cat show off their ice dance moves.You may be able to see in the screenshot of the arrangement that there are some extra percussion tracks called ‘cat perc’. Nick wanted to make it crystal clear to judges that he and Penny were hitting the right accents in the pattern dance, so he asked me to add percussion hits on those accented beats. He decided to shoot a quick video showing me which beats to emphasise, but with Penny still unable to walk, let alone dance, a substitute dance partner was needed. Which is how I ended up laughing fit to burst as I watched one of the world’s elite ice dancers in the hallway of his flat, dancing the rhumba with a cat as his dance partner! I have to admit that Milo the cat is a pretty nifty mover, actually.

From firewood to key percussion instrument: Rob’s home-made claves.Fighting to keep a straight face, I used the video as a timing reference and programmed MIDI parts for the percussion. For the actual sound I used a conga sample layered with claves, but my usual charity-shop claves were off-key and sounded odd. Luckily, as I was out in my woodshed stacking firewood that morning I’d noticed that some of the branches I’d cut down for firewood the previous year were nicely resonant, so I took a few of them indoors, bashed them together in front of a mic and sampled them. The resulting ‘clack’ was exactly right for the track, and in fact those branches (with the bark still on) are now my go-to claves in the studio. It’s Latin percussion, Finnish forest-style.

From firewood to key percussion instrument: Rob’s home-made claves.Fighting to keep a straight face, I used the video as a timing reference and programmed MIDI parts for the percussion. For the actual sound I used a conga sample layered with claves, but my usual charity-shop claves were off-key and sounded odd. Luckily, as I was out in my woodshed stacking firewood that morning I’d noticed that some of the branches I’d cut down for firewood the previous year were nicely resonant, so I took a few of them indoors, bashed them together in front of a mic and sampled them. The resulting ‘clack’ was exactly right for the track, and in fact those branches (with the bark still on) are now my go-to claves in the studio. It’s Latin percussion, Finnish forest-style.

Our slow first section was complete. Some compression and EQ on the tracks made everything hang together, and a pass through iZotope’s marvellous free Vinyl plug-in made it sound grainy and old, with roll-offs at the high and low ends, like something from a Cuban dancehall in the ’50s. Time to travel forward to the ’90s and tackle the second section.

Fast Forward

Rob’s MU Modular synth helped to generate several essential components of the eventual programme, including an epic filter sweep linking the first and second sections. We needed a transition from the 89bpm pattern dance section to the 106bpm ‘1994’ section. Simply stopping the slow section and starting the faster one sounded amateur, and gradually speeding up the audio was even less promising. I started testing various options and I found the best way to do it was, literally, with a bang. I created a rather seismic ‘boom’ by layering a deep descending resonant bass note from my Roland Jupiter 4, an explosive blast of filtered noise from my MU modular synth and a sampled drum hit from ‘Batucada’. Torvill & Dean’s rhumba then came rising up from the wreckage of this explosion in a dramatic filter sweep, before setting off with its original tempo and instrumentation.

Rob’s MU Modular synth helped to generate several essential components of the eventual programme, including an epic filter sweep linking the first and second sections. We needed a transition from the 89bpm pattern dance section to the 106bpm ‘1994’ section. Simply stopping the slow section and starting the faster one sounded amateur, and gradually speeding up the audio was even less promising. I started testing various options and I found the best way to do it was, literally, with a bang. I created a rather seismic ‘boom’ by layering a deep descending resonant bass note from my Roland Jupiter 4, an explosive blast of filtered noise from my MU modular synth and a sampled drum hit from ‘Batucada’. Torvill & Dean’s rhumba then came rising up from the wreckage of this explosion in a dramatic filter sweep, before setting off with its original tempo and instrumentation.

Of course, in that last sentence I merrily breezed past the words “dramatic filter sweep” as if it was trivial, but in fact it wasn’t that easy. The sweep was made using my modular synth as an insert effect, and I recorded over 20 different versions, some with this filter and then some with that one, some with filter changes automated using Expert Sleepers’ Silent Way, and some with the knobs twiddled manually. I tested them in an actual ice rink to see which was the clearest and most powerful on the ice. The eventual winner was a version where I used three filters in parallel (Corsynth, Happy Nerding and Yusynth, since you ask) plus an Oakley phaser, all set to different frequencies, one descending and the others ascending, and each running through a separate automated VCA to control volume. The sweep is only about three seconds long but it’s a ludicrously complex patch, and by the end I was beginning to run out of patch cables!

After the limited frequency range of the first section, it was important for the 1994 recording to sound big and lush. I used Tokyo Dawn Labs’ Kotelnikov for some gentle compression, and then MeldaProduction’s Spectral Dynamics to dynamically control intrusive frequencies and to adjust overall tonality. For a guy like me who spends a lot of time adjusting mixes to fit into acoustically horrible spaces, Spectral Dynamics is like a Swiss Army knife: it’s one of my desert island plug-ins and it’s tucked away somewhere in nearly all my mixes.

All of this work gave us a nice, solid-sounding middle section. The only place we did anything non-standard was during Penny and Nick’s inline lift, where their coach, ice dance legend Igor Shpilband, had requested some sort of effect to make it feel more soaring, more effortless. A parallel barber-pole flanger effect from Valhalla DSP, with a touch of roughed-up delay at the end courtesy of my beloved EHX Deluxe Memory Boy, did the trick.

Fireworks

The transition into the ‘Batucada’ section in Daisuke Takahashi’s programme was unbeatable for sheer excitement. We wanted to keep that hairs-on-the-back-of-your-neck moment, as well as paying tribute to Takahashi and his choreographer, but at the same time we couldn’t just nick the audio from his programme! It was time for some reconstruction. I passed the solo trumpet from the Prez Prado record through my modular synth for some extreme filter sweeps, and generated various subwoofer-bothering booms and whooshes from my old synths, which I layered up with drum hits from ‘Batucada’. It turns out, though, that there’s a limit to the number of ways you can name a channel that just has a huge explosive sound on it, which is why the screenshot is full of channel names like ‘Batu doof’ and ‘boooosh’.

For the third act, I had come up with a mash-up of Torvill & Dean’s ‘History of Love’ over ‘Batucada’ which was so infectious that Penny and Nick (and indeed Milo the cat, perhaps involuntarily) actually danced around their apartment when they heard it. Again, the “History of Love” sample came in with a rising filter sweep, and in a prime case of “can’t improve on the demo” syndrome, none of the hardware filter sweeps I tried later could quite match the sheer aggression of the free TAL-Filter plug-in I’d hastily bunged on the demo, so the VST stayed in the final version. At the end of the program I went into a bit of a brass-stab frenzy and layered up brass samples taken from all over ‘History of Love’ to create a big finish. Many tiny bursts of Valhalla DSP’s Valhalla Room reverb, another of my desert island plug-ins, on the tails of notes helped to glue it all together, and we had our short dance.

Rob Colling’s studio is, appropriately enough, in Eastern Finland, where there is plenty of ice.

Rob Colling’s studio is, appropriately enough, in Eastern Finland, where there is plenty of ice.

One Rink To Rule Them All

Mastering for ice rinks is a strange process. For me, it starts with macro-level mix automation to reduce the dynamic range: the quiet parts get a few decibels louder and the loud parts quieter. Rinks demand a certain amount of compression for audibility, but over-compressed music just dissolves into a wall of noise when it meets ice-rink reverb. So there’s a strict limit as to how much compression you can apply, and there’s no point wasting your allowance on something you can easily automate!

Next it’s time for a mastering chain, which on Penny and Nick’s programme meant the Ableton Utility plug-in to sum the output to mono, then Spectral Dynamics and iZotope’s Ozone, with Voxengo Span for metering. In this instance Spectral Dynamics was working as a kind of spectral limiter, with an infinite ratio and a very high threshold, so that it just capped the level of the most piercing notes — a very necessary precaution against nasty resonances in certain ice rinks. Ozone was providing some gentle EQ as well as some full-range compression and a fairly bold 3.5dB level boost into a limiter.

I can make educated guesses and get the mix 90 percent of the way there using the Blue Sky monitoring setup in my studio. But I’ve learned that no matter how many hundreds of skating programmes I’ve edited, something always surprises me when I hear a piece of music in a real ice rink. There’ll always be some frequency that leaps out, some rich, long reverb tail that just isn’t audible, or some instrument I thought I’d tucked neatly away that suddenly makes everyone cover their ears. My local skating club (Joensuun Kataja Taitoluistelu) and the city of Joensuu are kind enough to let me use their ice arena during quiet times, so I head down there with my laptop and my interface once or twice a week to test my mixes.

In case you ever need to know how to walk on an ice rink, it’s a kind of shuffle, where you put your weight over each foot early without ever lifting your feet off the ice. It makes you look a right twit, but it’s worth it to get out onto the rink and listen critically from the skaters’ perspective. I’ve picked up all sorts of problems that don’t manifest themselves in the studio — magical John Williams flute runs that scorch your ears off, or a thunderous Hans Zimmer bass line that dissolves into mush — so I make a point of listening to all my programmes in the rink now.

Doing so with Penny and Nick’s programme revealed the need for a few EQ and level tweaks, and I used Spectral Dynamics once again, this time for some spectral ducking with a side-chain to bring ‘History of Love’ forward in the final mashup section without increasing the overall level. Initially I also reined in the bass a little in the ‘Batucada’ section to minimise low-end mushiness and resonances. However, when I talked to Nick about it, he wasn’t so keen. Apparently some of the other elite-level teams are using seriously bassy dance music this season — Pitbull was mentioned, somewhat to my dismay — and so I was not, under any circumstances, to skimp on the sub-bass! Instead I used a second instance of Ozone on the ‘Batucada’ channel, with the dynamic EQ acting as an expander below 80Hz to clean up the gaps between the kick-drum hits. The result was a tighter low end which I could push much harder to get the sequinned-trouser-flapping sub-bass that Nick wanted.

Not Like It Used To Be

With 51 tracks and 91 plug-in instances, the dance sequence eventually proved too much for Rob's MacBook Pro.The finished short dance is simultaneously a remix, a remaster and a mashup. With 51 tracks and 91 plug-in instances, it eventually proved too much for my MacBook Pro, so it’s a good job I built a more powerful studio PC earlier this year!

With 51 tracks and 91 plug-in instances, the dance sequence eventually proved too much for Rob's MacBook Pro.The finished short dance is simultaneously a remix, a remaster and a mashup. With 51 tracks and 91 plug-in instances, it eventually proved too much for my MacBook Pro, so it’s a good job I built a more powerful studio PC earlier this year!

It strikes me that the production process has been very different to the creation of Torvill & Dean’s 1982 Olympic-winning Bolero music, which involved my hero Alan Hawkshaw overlaying track after track on his Fairlight. My 21st Century version has more to do with the art of the DJ than that of the orchestral arranger, relying on software capabilities such as warping, note removal and spectral compression, which simply didn’t exist in the days of Bolero, or indeed when ‘History of Love’ and ‘Batucada’ were recorded.

For me it’s been a hugely rewarding and surprisingly collaborative process, almost like a band where two of the members just happen to play skates and ice rather than bass or drums. But, just as with Torvill & Dean, it all boils down to three minutes on the ice, under the Olympic logo, in front of the world’s cameras. This short dance is Penny and Nick’s now, and what happens to it is up to them. Which just leaves me to prepare myself to leap around my living room when they skate the program at the Winter Olympics in February… and to look forward to whatever marvellous lunacy they bring me next season!

Balancing On Ice

An ice rink is one of the most unfriendly acoustic environments I can think of: a huge empty space with a lousy sound system, no absorptive material at all and an almost perfectly reflective floor! The reverb in a typical rink can exceed 10 seconds in the lower frequencies, and there will usually be enough resonant standing waves to sink a ship (or at least vibrate it to pieces). To sound great on the ice, a piece of music needs to sound very flat and dry, with the high end emphasised and the low end very tightly controlled. In a sport where most speaker systems are badly installed and/or worn out, and where the loudness and general impressiveness of your music can be a potential competitive advantage, your music had better also be bloomin’ loud! This is, sadly, one situation in which the loudness wars are very much still being fought.

There’s one more thing: for music to work properly in an ice rink, it needs to be in mono. Even if you could, theoretically and miraculously, plonk the entire audience in the sweet spot between the two stereo sources, the skater would still be zooming around all over the rink, sometimes hearing only the left signal and sometimes only the right. In a sport where staying in time and really feeling the music can make the difference between winning and losing, stereo would be suicidal. And that’s before you go to a rink where they sum the signal to mono by, er, throwing the right channel away! I have been at several competitions where entire instruments have just vanished from someone’s programme because only the left output of the mixer was connected.

In short, editing ice skating music may be all about finesse but mixing it definitely isn’t. If you want it to work, make it completely badass, bombproof… and monophonic.

Short Dance, Long Rulebook

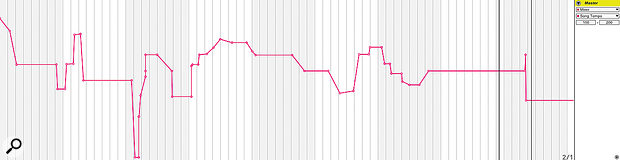

Creating a suite of music that fits with the desired choreography and the ISU’s competition rules can require extremely detailed manipulation of tempo. This is the Ableton Live tempo map for the finished programme.

Creating a suite of music that fits with the desired choreography and the ISU’s competition rules can require extremely detailed manipulation of tempo. This is the Ableton Live tempo map for the finished programme.

A modern competitive ice dance performance consists of a short dance and a free dance, usually performed one day apart. Ice dance music is migraine-inducingly complex at the best of times, but short dance programmes are a breed apart. There are pages and pages of rules covering consistency of tempo, the lengths of intros and endings, the changes in tempo and style that you have to include, and the need for an audible rhythmic beat throughout the piece. (You’re allowed 10 seconds without a beat, by the way, for the dancers to pack in all the freestyle madness they’ve been bottling up, and then it’s back to the rhythmically consistent grindstone…)

On top of all that, every year there is a new shortlist of permitted musical styles and an obligatory pattern dance which all ice dance teams around the world have to include in their short dance programme. This pattern dance is a set series of moves, to be danced in a set order in a particular place in the rink and to a given tempo, and it’s chosen by the International Skating Union (ISU) each year from a carefully maintained repertoire of dances. Suffice to say, it’s quite hard to make a legal short dance programme that doesn’t sound like a fight in a DJ booth!