Don't have a bass handy? Try playing a bass part on electric guitar, then using Melodyne's Sound Editor to beef up the sound before running it through a bass amp simulator...

Don't have a bass handy? Try playing a bass part on electric guitar, then using Melodyne's Sound Editor to beef up the sound before running it through a bass amp simulator...

Used right, amp modelling plug‑ins can sound almost like the real thing. But it's much more fun to use them wrong!

Amp modelling plug‑ins have some obvious advantages over real guitar amps. They let you record heavy metal guitar solos without antagonising the neighbours. They give you a range of sounds that would take a roomful of hardware to match. And, in the mixed blessings department, they mean you don't have to make up your mind about guitar sounds until the final mix.

Of course, depending on computer code for your guitar tone has its disadvantages. You need a soundcard with low-latency drivers to approach the responsiveness of a real amp, and diehards still complain that the sound doesn't quite capture the magic they get from smouldering valves and clanging reverb tanks. However, there are also a lot of things you can do with plug‑ins that no vintage fire hazard will ever manage. In this article, I'm going to suggest some less obvious uses for software amp emulations.

Audio Examples

Click below to download the hi-res Audio file that accompanies this article or just use the MP3 SoundCloud player for convenience.

Upping The Ampte

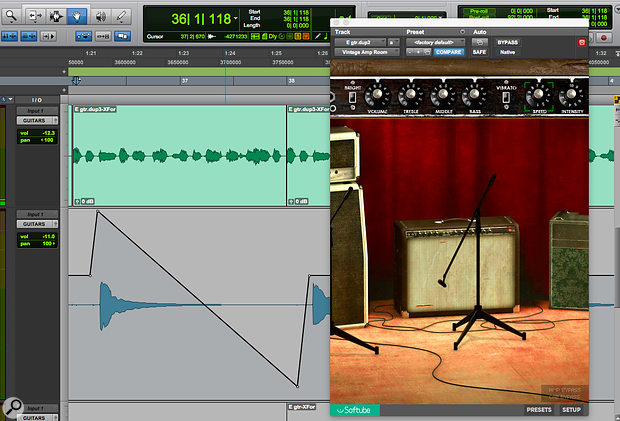

An amp modelling plug‑in allows you to use as many virtual amps simultaneously as you like. The applications of this are legion. For instance, many guitarists working with real amps like to use a splitter box to send their signal to two or even more amps simultaneously. The easiest way to do the equivalent in most DAWs is simply to copy the unprocessed guitar part to as many tracks as are required, and insert an amp modelling plug‑in across each one. By experimenting with different settings and panning arrangements, you can conjure some huge guitar sounds this way, and it often allows you to combine the best aspects of several amps in one sound.

Better still, the flexibility of plug‑ins allows you to go way beyond what's possible with real amps. For instance, you can use automation to vary the balance between the different tracks, thus giving the impression of morphing from one guitar sound to another. By using auto-panning or tremolo on one of the tracks, while keeping a fixed setting on another, you can create movement in the sound without sacrificing its solidity. You could wheel out the old trick beloved of Eventide and AMS harmoniser users, applying modulated pitch-shift of a cent or two to different parts and hard-panning them to create width. You could even use the polyphonic version of Melodyne to split your guitar track into separate notes and route them to two or more different amp simulators, or pitch-shift one of your duplicate parts up an octave. Or try splitting a single guitar part into separate low- and high-frequency elements using a crossover filter and passing these separately to different amp simulators: this can be especially effective on bass, where you want to maintain a constant presence in the sub-150Hz region while allowing the mid-range more freedom to snap and snarl.

Automation

Apparently Neil Young has a custom-built mechanical system for automating the controls on his array of vintage guitar gear. Those of us who are not lucky enough to afford the services of a full-time guitar tech need not despair, though, as any decent amp modelling plug‑in will afford even greater flexibility; and, what's more, your moves can be recorded and replayed.

The most obvious use for automation in plug‑ins which have built-in pedalboard emulations is to turn the virtual stompboxes on and off. This is all very well, but if you only use your sequencer's automation facilities as a kind of glorified footswitch, you'll be ignoring some of the potential of these plug‑ins.

A more subtle use of plug‑in automation is to adjust the amp model's EQ settings to complement the arrangement of your song. Where your song begins with an exposed electric guitar part, you might want a thick, full-range tone; but when the drums, bass and piano come in, you may well want to roll off some of the bass to avoid conflict in this region. You could simply leave the amp model's tone settings the same and insert an EQ plug‑in afterwards, but you'll get different and perhaps better results by automating the amp modeller itself. Similarly, heavy reverb might be suitable for an exposed guitar part, but will tend to turn everything to mush in a busy arrangement, so why not use plug‑in automation to back off the amp modeller's reverb during the chorus?

Automating tremolo speed can be a very effective move.

Automating tremolo speed can be a very effective move.

Periodic effects such as tremolo and delay also benefit hugely from the possibilities provided by automation. If tremolo speed can be sync'ed to the tempo of your host sequencer, for example, it can be made to follow any tempo changes in your song. Where a song ends with a ringing guitar chord or note, try using automation to deepen the tremolo or vary its speed. You can also add interest to endings by suddenly upping the amount of delay and delay feedback just before the song stops. A perennial problem with using lots of delay on a guitar part is that it sounds great until you change chords, whereupon you're left with repeats of the last chord clashing with the new one. If you're getting this problem, try using automation to duck the delay for a suitable interval before each chord change.

Treating The Raw File

One of the most useful features of guitar amp simulation plug‑ins is that they can help mask some quite serious problems with whatever you're putting through them, without necessarily changing it beyond all recognition. Even relatively clean settings can disguise horrors such as digital clipping on transients to a surprising extent. If you're ever faced with a badly recorded guitar part, even one that's played on an acoustic guitar or through an amp, try putting it through an amp modeller.

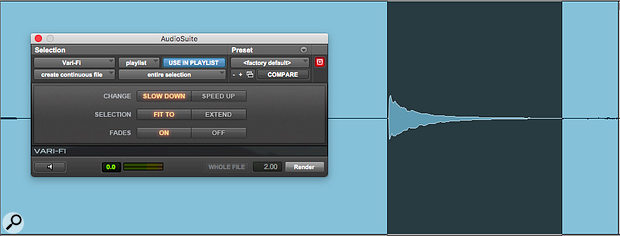

Offline plug‑ins such as the venerable Pro Tools Vari-Fi can be used to apply tape stop effects to the raw audio. When fed through an amp simulator, this can achieve quite a neat dive-bomb effect.

Offline plug‑ins such as the venerable Pro Tools Vari-Fi can be used to apply tape stop effects to the raw audio. When fed through an amp simulator, this can achieve quite a neat dive-bomb effect.

The flattering qualities of amp simulation can be put to more creative uses, too. Pitch-shifting algorithms aren't usually transparent enough to allow you to transpose anything more than a couple of semitones without obvious side‑effects — but if what you're processing is going through an amp modeller, you can get away with much more radical changes. You can do effective swoops and dives in pitch by progressively increasing the amount of pitch-shifting you apply to a note. Even pitch changes of an octave or more can often work when the results have been mangled by a virtual amp.

You can also create interesting results by editing and processing the raw guitar file before it goes through the amp modeller. Try chopping small sections of guitar out for an interesting stuttering effect that's nothing like tremolo. A piece of guitar that's been reversed before being fed through an amp modeller sounds quite different to what you get by reversing a guitar part that's already been through an amp. And there are innumerable other treatments that can be dished out to the raw guitar part. Reverse reverb, resonation, vocoding and Auto-Tuning can all produce distinctive effects, as can noise–reduction and reverb-reduction plug–ins.

Amp and cab simulations can add that elusive 'knock' or 'thump' to a kick drum, floor tom or bass instrument that is flabby and undefined.

Not Just For Guitars

Real valve amps are widely used not only on guitars, but also on basses, electric pianos, organs and sometimes vocals. Amp simulators can shine on all these sources and more. I frequently receive multitracks to mix where background synth, vocal, percussion or keyboard parts overshadow the 'real' instruments, either because they have far more top end, or a massive stereo spread, or both. An amp simulator with a cabinet emulation is usually mono, and has a limited bandwidth which is perfect for cutting them down to size — quite often I'll disable the amp part altogether and just use the cabinet simulation.

At the bottom end, amp and cab simulations can add that elusive 'knock' or 'thump' to a kick drum, floor tom or bass instrument that is flabby and undefined. Or, if you use a small speaker emulation, they can be an effective high-pass filter. Emulations of cheap small amps make excellent 'telephone vocal' effects, preserving intelligibility and clarity whilst squeezing the entire vocal into a narrow bandwidth. Try cranking up the spring reverb and placing an amp sim on an aux bus as a send effect, for that vintage vocal vibe.

Cab simulations used on their own can be perfect for darkening and thickening a plug‑in reverb, delay or other auxiliary effect. They also work well on drum room mics, where the natural high-frequency roll-off of the cabinet tames harsh cymbals and the low-mid 'cabinet thump' adds meat to the kick and snare. More brutal amp settings can work well as parallel effects: send from your drum close-mic tracks to a crunched-up Marshall, then fade in just enough to give too-clean drums a bit of extra bite. Doing the same with a vocal track can add some rock & roll excitement to a safe studio performance.

Cutting out or reversing fragments of the raw audio file creates a jarring effect that's instantly attention-grabbing.

Cutting out or reversing fragments of the raw audio file creates a jarring effect that's instantly attention-grabbing.

Finally, many amp modellers aren't just amp modellers. They are also convolvers that can load an impulse response and apply it to the guitar sound. The theory is that you're supposed to choose an impulse response taken from a miked loudspeaker cabinet, but you don't have to. You can use any audio file, as long as it's short enough! Try snipping out interesting fragments from other tracks in your project, and loading those into your amp modeller's IR slots.