David Bowie.Photo: Frank Ockenfels 3

David Bowie.Photo: Frank Ockenfels 3

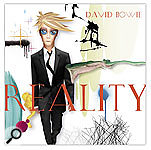

For the 2002 album Heathen, David Bowie and Tony Visconti revived one of the greatest artist/producer partnerships in pop history. Following the success of that project, the duo have again worked closely together on Bowie's new album, Reality.

"I feel that reality has become an abstract for so many people over the last 20 years," says David Bowie when questioned about the topic that lends itself to the title of his latest album. "Things that they regarded as truths seem to have just melted away, and it's almost as if we're thinking post-philosophically now. There's nothing to rely on any more. No knowledge, only interpretation of those facts that we seem to be inundated with on a daily basis. Knowledge seems to have been left behind and there's a sense that we are adrift at sea. There's nothing more to hold onto, and of course political circumstances just push that boat further out."

Coming only 15 months after the release of the critically acclaimed, million-selling Heathen, David Bowie's 26th studio album sees him setting familiar lyrical issues against a mostly more hard-edged, rock-oriented musical backdrop. Once again, Tony Visconti, who worked on nine Bowie albums between 1969 and 1980, is his co-producer and engineer, and it is the two men's shared intuitiveness and vision, as well as the sheer ease of their collaboration, that imbue Bowie with a sense of confidence and musical contentment on Reality that was largely missing from his recorded work during the 22 years that followed Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps).

"Before we went in with Heathen, we had been talking for a good few years about working together again," Bowie now recalls. "However, we did promise ourselves that it would be a special project, that we wouldn't rush in just for the sake of it, and I really felt that I had two or three threads of ideas that would be fabulous for Tony and I to work on. So, we made Heathen our kind of debut reunion album. The circumstances, the environment, everything about it was just perfect for us to find out if we still had a chemistry that was really effective. And it worked out. It was perfect, not a step out of place, as though we had just come from the previous album into this one. It was quite stunningly comfortable to work with each other again."

Producer Tony Visconti.Photo: Mario McNultyAt the same time, Tony Visconti encountered the kind of progression that he'd expected with regard to Bowie's musical sensibilities when the two of them reunited for the Heathen project. "His knowledge of harmonic and chordal structure had vastly improved," Visconti remarks. "This had already been good when I last worked with him, but now there was more depth to his melodic and harmonic writing. I had developed too, so we'd kind of moved in a parallel way along the same route. We were definitely on the same wavelength. A part of him wants commercial success, but there's a bigger part of him that has great artistic integrity, and it was therefore more important to him for Heathen to make a great artistic statement."

Producer Tony Visconti.Photo: Mario McNultyAt the same time, Tony Visconti encountered the kind of progression that he'd expected with regard to Bowie's musical sensibilities when the two of them reunited for the Heathen project. "His knowledge of harmonic and chordal structure had vastly improved," Visconti remarks. "This had already been good when I last worked with him, but now there was more depth to his melodic and harmonic writing. I had developed too, so we'd kind of moved in a parallel way along the same route. We were definitely on the same wavelength. A part of him wants commercial success, but there's a bigger part of him that has great artistic integrity, and it was therefore more important to him for Heathen to make a great artistic statement."

Clearing The Decks

Released to coincide with his first world tour in nearly a decade, Reality contains nine new Bowie compositions in addition to a couple of covers: the Modern Lovers' 'Pablo Picasso' and 'Try Some, Buy Some', an obscure George Harrison number that he and Phil Spector produced for Ronnie Spector back in 1971. As with the pair of covers on Heathen, both songs were selected from an oldies list that Bowie once compiled for a proposed but never realised Pinups II album.

"These days, it's great to be able to record more frequently and clear the decks of the songs I'm writing," he says. "For me, this is a far preferable way to go, and it does resemble the way that I've worked in the past. I had a spate of being able to do that in the early '90s, and I would have liked to work Outside [1995] and Earthling [1997] against each other a lot faster, but at the time we had a major problem even finding somebody to put Outside out, because it was such an odd album. In the '70s, I think I probably over-achieved — I was doing two to three albums a year, co-writing with Iggy and putting my own albums out. It was insane. Some years I put out two albums, but there was consistently at least one album a year, and I think I find an album a year very comfortable. It doesn't faze me at all, and it tends to follow the pattern and the rhythm at which I write.

"It's kind of cathartic, and Columbia are pretty cool about it, so it's great. They said they would agree to this when I first took my ISO label to them — I said, 'Look, I will require that I can put out stuff when I want to, and I don't want to have one of those sell-through dates inflicted on me,' which is what you usually get: 'Oh, we've got another 18 months until you can do that.' They've been great so far, and when I hit them with a new album they're ready for it."

So Much For The City

While the main man played rhythm guitar, keyboards and sax on Reality, it was his touring band that provided much of the accompaniment: drummer Sterling Campbell, pianist Mike Garson, and guitarists Earl Slick and Gerry Leonard. Regular bass player Gail Ann Dorsey performed backing vocals alongside Catherine Russell, musical arranger Mark Plati took over on bass, and Tony Visconti also contributed bass, backing vocals and mandolin.

It was at the end of the Heathen sessions, and also following the subsequent mini-tour, that Bowie began writing songs for what would become Reality, as well as its bonus-track-enhanced Special Edition.

"There's a part of David Bowie that definitely does not want to repeat himself, so we were committed to avoiding the Heathen formula," says Visconti. "We realised that we'd created this kind of genre for Heathen, and we wanted to go in another direction. I'd referred to that album as his 'magnum opus' — I told him, 'That was more like a symphony, and you can't write too many of those.' I mean, the great composers didn't write a new symphony every couple of months. Heathen consisted of very broad strokes and a grand sonic landscape — there were layers and layers of overdubs — whereas for Reality he wanted to change to something that he and his live band could play on stage with great immediacy, without the need for synthesizer patches and backing tracks. He wanted to make this more of a band album."

Still, Bowie himself asserts that he never approached this project with any preconceived ideas. "It really doesn't work like that," he says. "The album does tend to become the animal it is at the time of the making. Unless I've got some conceptual piece in mind, I don't go into it with a real premeditated idea of what it's going to turn out to be. As I knew that we were going to continue touring this year, I was looking for something that had a slightly more urgent kind of sound than Heathen, but I think the mainstay of the album is that I was writing it and recording here in downtown New York. It's very much inspired by where I live and how I live and the day-to-day life down here. There is a sense of urgency to this town. The engine of it is therefore a lot more street-beat than, say, Heathen, which by virtue of the fact that it was written in the mountains, had a much deeper, more majestic, tranquil kind of quality to it.

"The albums that I've written out of character with the place where I'm living have often been failures. They don't work so well, it's very odd. Still, [Reality] is not my New York album. I didn't want it to be saying 'This is what New York's like right now.' There really was no through line, it is just a collection of songs. Because of the way that Tony and I work together, there's some kind of continuity throughout, but that's more in the style of production. There was very little struggle to find what would be right for the album. In all, I think we only left off two or three songs.

"I really don't have a general approach to songwriting. Sometimes I'll inflict rules like 'All right, this piece can only have five chords,' and go from there, because it can be good to set parameters. Then again, I've developed such a lot of different processes over the years, ranging from accidents of looping — taking three or four chords and looping them in a particular way, and then writing a melodic theme over the top of them — to old-fashioned, crafted songs. I guess something that was virtually looped on this album was 'Looking For Water', and so a secondary consideration was the melodic content on top, whereas 'She'll Drive The Big Car' was specifically a written piece. It's self-evident when you know that and then hear the songs."

In general, Bowie tends to write fairly quickly — 'Fall Dog Bombs The Moon' was completed in about half an hour. Yet there are also songs that get stuck in the creative process while he keeps reworking the lyrics. Such was the case with 'Bring Me The Disco King', an introspective number that was originally conceived back in the 1970s, and which in its realised form features just Bowie with Mike Garson on piano, as well as the looped drums that Matt Chamberlain played during one of the Heathen sessions.

"That's the only track on the album where we utilise the drumming of Matt Chamberlain, even though he was playing to a completely different song," says Tony Visconti. "The way that he played was so seductive, so melodic and so beautiful, that we just recorded 'Disco King' over the loops that I'd made of his performance."

Through The Looking Glass

Following a couple of days in November 2002, the Reality sessions proper took place at Looking Glass Studios in Manhattan from early January to late May of 2003, usually running from about 11am to 8pm, five to six days a week, and mostly utilising the Studio B room that is rented by Tony Visconti. "I'm very proud that Philip Glass is my landlord," he says. "He's a smashing guy, and when we were recording he'd occasionally poke his head into the control room, have a listen and offer very encouraging advice."

Looking Glass Studio B. The MCI desk was used to mix Reality, though automation and level changes were handled within Logic.Photo: Eleonora Alberto

Looking Glass Studio B. The MCI desk was used to mix Reality, though automation and level changes were handled within Logic.Photo: Eleonora Alberto

At the demo stage, Bowie brought in four or five tracks that he had already written in his pretty basic home setup. This includes a Korg Trinity keyboard, a vintage ARP Odyssey synth, a Korg Pandora effects processor, a collection of acoustic and electric guitars, and a few small amps. "I don't want my home to be taken over by the recording process," he explains. "I'm very wary of that. I really saved everything for working over at Looking Glass."

In all, about seven songs were demoed before Bowie and Visconti then decided to try some overdub ideas: vocals, extra rhythm guitars, extra keyboard passes, and so on. "Inevitably, we'd hardly redo anything," Visconti says. "I always record things carefully in the first place, because I know we're not going to redo them, and so a lot of the demo parts ended up on the final version."

After a short break during which Bowie wrote some more songs, the whole process started over again. In combination with Looking Glass Studio B's MCI JH600 console and selection of microphones, Visconti has a lot of his own gear there, including Genelec and KRK monitors, as well as outboard gear that was hired especially for the Reality project. Since the bulk of the album was recorded into Logic Audio, the MCI board was basically used only for monitoring.

Some of Tony Visconti's own outboard gear. From top: Universal Audio 2-610 mic preamp, the Avalon VT737SP preamp used for Bowie's vocals, Presonus ACP88 eight-channel compressor, Focusrite Red preamp, Furman power conditioner, Aphex 109 stereo EQ, ART Pro VLA compressor and Pro MPA preamp, Dbx 166a dynamics, Alesis 3630 compressor (x2), Dbx 163X compressor (x8), BBE Sonic Maximiser and Alesis graphic EQ.Photo: Eleonora Alberto"We fed all of the vocals through an Avalon VT737SP, which is a preamp, equaliser and limiter/compressor all in one, and we hardly used the MCI at all," Visconti explains. "In fact, when we recorded drums, we used something like 12 outboard preamps."

Some of Tony Visconti's own outboard gear. From top: Universal Audio 2-610 mic preamp, the Avalon VT737SP preamp used for Bowie's vocals, Presonus ACP88 eight-channel compressor, Focusrite Red preamp, Furman power conditioner, Aphex 109 stereo EQ, ART Pro VLA compressor and Pro MPA preamp, Dbx 166a dynamics, Alesis 3630 compressor (x2), Dbx 163X compressor (x8), BBE Sonic Maximiser and Alesis graphic EQ.Photo: Eleonora Alberto"We fed all of the vocals through an Avalon VT737SP, which is a preamp, equaliser and limiter/compressor all in one, and we hardly used the MCI at all," Visconti explains. "In fact, when we recorded drums, we used something like 12 outboard preamps."

While drummer Sterling Campbell was in the isolation booth, rhythm guitarist Bowie and bass player Mark Plati were crammed alongside Tony Visconti into the compact surroundings of the Studio B control room. Studio A would have afforded a more spacious live area, but neither Bowie nor Visconti wanted to work there.

"We wanted the record to have a real tight New York sound," Visconti says. "David loves the sound of Studio B. We did a little bit of work in there at the end of Heathen, and it was because we liked it so much that I started to rent it. Then, when he wanted to work at Looking Glass again for these latest sessions, I assumed we were going to book Studio A, but he said, 'No, I want to do as much as I can in your room.' The monitoring in there is terrific, and anything that I bring out of that room sounds really good, whereas in Studio A I'd have to second-guess the bass. Low end is a little hard to judge in there.

"Before the band came in, I'd played bass on all of the demos, and some of my bass parts eventually made it all the way to the album in preference to Mark Plati's. This was the case on 'New Killer Star' — Mark had a go at it, but there was some kind of personality in my bass playing that David preferred, and the same applied to 'The Loneliest Guy', 'Days' and 'Fall Dog Bombs The Moon'. It's Mark's bass on all of the other tracks, including the part that I wrote for 'Looking For Water', and while on some numbers it was DI'd, on others he used the new [Line 6] Bass Pod, dialling up a specific bass amp and bass cabinet and fooling around with the effects. That was quite interesting, although I'm not totally in love with it. Things like Pods often have too much of a room sound, or they have what is their idea of an amp sound, and maybe that isn't where I would place a mic in front of an amp, so if that wasn't working I much preferred going to DI as we didn't have the room for a real amp. I myself have a very souped-up '67 Precision — a talented guy in London named Roger Giffin put DiMaggio pickups near the bridge and a very fat Telecaster pickup near the neck, and over the years I've played it on a number of Bowie tracks. Marc Bolan also played it. That bass has five or six different sounds, and I love playing it through a DI. I don't like to play through amps."

Sketching The Outlines

While the rhythm section of drums, bass and rhythm guitar was tracked live, lead guitar parts weren't recorded until later since a lot of the songs' final structures hadn't yet been determined. "The melodies were sketchy, the lyrics were sketchy, and so there was no point in recording lead guitars and other things at that stage," Visconti explains. "Sterling, Mark and David would often play along to a click track that we had on the demos, consisting of a basic drum loop from a drum box, together with a scratch keyboard or scratch guitar and David's vocal. That would already be on tape — in this case, Logic — and then he would play another rhythm guitar along with the other two guys just to give the track some feel.

The remote control for Studio B's Otari analogue reel-to-reel recorder, with a selection of outboard gear.Photo: Eleonora Alberto

The remote control for Studio B's Otari analogue reel-to-reel recorder, with a selection of outboard gear.Photo: Eleonora Alberto

"We initially recorded to 16-track analogue tape because I just love the sound. I'd talked David into working that way on Heathen — I told him it was really worth doing, because we'd capture the analogue compression and warmth on digital. When we'd transfer it, the sound would still be there, and that proved to be right on Heathen, so we started this new album in exactly the same way. I used about 10 tracks for drums, as well as one or two tracks for the bass and one or two tracks for the guitar. We'd then fly those 13 or 14 tracks over into Logic.

"I used fairly conventional miking for the drums, and David would always give me ample time to set them up properly. He's really, really patient that way. If I told him I needed a day to set something up, he'd be fine with that. There was a D12 on the kick, together with an RE20 placed just inside the skin near the beater for more attack, and I routed both of these to one channel and mixed them together. I wouldn't have two kick drum mics, but I did try a little experiment where I had a bass amp in the drum booth and ran one of the kick drum mics through that. That made the kick really loud and it sounded good, so I used it on a few tracks. It didn't suit every track, and sometimes it created too much boominess, but it really worked on certain types of music. I've actually used that technique before, but in much larger studios where I could really crank up the amp and place it at the other end of the room. Since this was in the Studio B iso booth, which measures 12 feet by 10 feet with a nine-foot ceiling, we probably hit a kind of resonant frequency on some tracks, and in that case I just switched off the amp.

"I miked the snare drum top and bottom with SM57s, while for the hi-hat I used these little AKGs that usually clip onto tom-toms for live work. I clipped them onto the rod of the hi-hat stand, just above the top cymbal, and taped the lead to the ceiling in order to avoid another microphone stand. I hate microphone stands because they just get in the way and reflect sound, and so I try to avoid them as much as possible. In fact, I even put the D12 inside the kick, resting on a pillow, whereas I did have to put the RE20 on a stand so that I could aim it directly at the beater.

Both Looking Glass studios feature vintage Neve desks used for their preamps, as well as the main studio mixers. This is the BCM with 1073 preamps and EQs in Studio A.Photo: Eleonora Alberto"The tom-toms were miked with Sennheiser 421s, while I used a pair of Calrecs for the overheads. There was also a pair of good old-fashioned PZMs in the corners of the iso booth and they were really great. I could have used those tracks as the entire drum kit — the mics were high up in the corners of the room, but they picked up enough kick drum, snare, everything. They're such amazing mics, they never cease to amaze me. As in any studio situation, I had a fair amount of compression on the snare and the kick, and I also compressed the PZMs slightly, so when it was played back the drum sound was really rocking."

Both Looking Glass studios feature vintage Neve desks used for their preamps, as well as the main studio mixers. This is the BCM with 1073 preamps and EQs in Studio A.Photo: Eleonora Alberto"The tom-toms were miked with Sennheiser 421s, while I used a pair of Calrecs for the overheads. There was also a pair of good old-fashioned PZMs in the corners of the iso booth and they were really great. I could have used those tracks as the entire drum kit — the mics were high up in the corners of the room, but they picked up enough kick drum, snare, everything. They're such amazing mics, they never cease to amaze me. As in any studio situation, I had a fair amount of compression on the snare and the kick, and I also compressed the PZMs slightly, so when it was played back the drum sound was really rocking."

Nevertheless, once the big, heavy guitar solos had been added to rock tracks such as 'New Killer Star', 'Pablo Picasso' and 'Looking For Water', the co-producers felt that the drum sound was still missing a certain ambience and explosiveness that had been present on Heathen. So, what to do? Well, since that album had been recorded at the extremely spacious Allaire Studios in upstate New York, about two hours north of Manhattan, the only logical thing was to make a quick trip there and play the Looking Glass drum tracks through the huge ATC SCM150 monitors in Allaire's Neve Room at a very loud volume, capturing said ambience with the aforementioned array of mics.

"We put the monitors exactly where we'd put the drum kit two years ago and we pointed them slightly upwards at a 45-degree angle so that they were shooting upwards and outwards," Visconti explains. "We also had a pair of Earthworks mics hanging from the rafters, about 25 feet above the monitors, which is exactly where they were above Matt Chamberlain's drum kit during the Heathen sessions. We put them through the same preamp and the sound was there automatically. We then recorded this on a pair of tracks in Logic and brought it back to Looking Glass to use in the mix. The result is that there might be a slight difference, but overall it sounds as if the drum kit was at Allaire. This is especially so on 'Pablo Picasso', while about 40 per cent of the drums on 'Looking For Water' was captured in the Allaire room. It's got a nice one-second decay in there, which is ideal for drums."

The Supro Sound

When Reality got underway, Bowie had only recently invested in several Supro guitars, one of them a hard-to-find white model similar to that played by Link Wray on 'Rumble'. He'd managed to pick this up on eBay (I kid you not) and had it revamped by Staten Island designer/ manufacturer/ restorer Flip Scipio. After Scipio went to work on it, Bowie ended up with a guitar that, according to Tony Visconti, "was never meant to sound so good", and he played this a lot during the Reality sessions, along with a Supro 12-string that had also been overhauled by Flip Scipio, and some harsh-sounding Supro valve amps.

"We'd either put a Supro amp in another little room that we found off to the side of the studio, or David would play through his little Korg Pandora DI box which has a load of effects in it," Visconti recalls. "Often he'd play that for the vibe track, and then when the band left he would redo his parts through the Supro.

"When they were playing, the band could hear the click track and David's guide vocal plus their own instruments, and for that we had quite a foldback setup. Basically, while the bass player was listening on monitors with me — occasionally he'd wear headphones too — I was only able to give the drummer one foldback, and he needed me to provide him with a very specific mix. That took quite a bit of work, but after a few days we got it right and the communication was great. There was no problem with David and Mark, because they were listening to my mix and they liked it. It was just the drummer's mix which proved difficult. He'd want to hear his own drums in there, plus the mix, and he wanted it all very loud, so we had to really crank the headphones and we ended up blowing out a couple of pairs."

Recording Vocals

The first rhythm session lasted eight days and covered eight tracks, after which there was some overdubbing of rhythm guitars and vocals onto these tracks just to see if everything was working. "It's always a work in progress," Visconti says. "We would record vocals and have no idea as to whether we'd keep them, and by the end of the album I'd have at least three different vocal sessions for each song: vocal one, which David did right after the rhythm section had been tracked; then a midway vocal take; and then towards the end of the album he'd have yet another try at nailing it. Sometimes we'd even retain a line or two from the demo vocals, and we worked consistently with the same mic and same Avalon preamp. David bought himself the Manley Gold Reference stereo mic about 10 or 12 years ago — he'd kept it in storage, and when he asked me if I'd be interested in trying it out, I said 'sure'. I love anything made by Manley, and so we took the mic out of mothballs for Heathen, and it worked so great that we used it again on this album.

"Any vocals that we did in February were matched up with any vocals we did in May. We could easily cut from one vocal track to another. Each time, David would usually do two passes and call it quits, because he goes for feel and passion. He sings great, he's always singing in tune, he always sings full voice, so there's never any need for eight or nine David Bowie vocal takes. I know it and he knows it, so there was never any point where I had to do an enormous comp. It would just be down to a choice between track one or track two, and maybe we'd comp in a particular line that he'd recorded two months earlier.

"Again, even though he likes to get the vocals done really quickly, David was very patient when, in the beginning, I told him I wanted to play with his vocal sound a bit. I said, 'I'd like a few hours or maybe half a day to get a great sound, and then afterwards we can just punch in at any point.' So, everything was well thought out and I didn't have to do anything by the seat of my pants. I really appreciate it when an artist affords me that amount of time.

"Recording David's voice is very easy. He's got great chops. He just goes in front of the mic without warming up at all. He's gifted and he's also intuitive — he knows how to sing. Sometimes I would coach him if I needed to remind him about something he'd done earlier, or I might make a suggestion — some line might require more angst or whatever — and he's receptive to anything like that. He's a consummate professional, and I'm really blessed to be working with such a great singer. Also, he recently gave up smoking, so he's recaptured some of his high range. He'd lost at least five semitones, and he's now gained most of them back. I mean, in the old days he used to sing 'Life On Mars' in the key of C. Now he has to sing it in the key of G."

Ambient Guitars

David Torn, who played all of the ambient guitar parts on Heathen, was recruited once more to provide Reality with some extra texture. His parts were performed over the course of 10 days, and the results are easily identifiable on the finished record — just listen to the stuttering riff that helps launch 'New Killer Star'. On the other hand, the stuttering flamenco guitar at the beginning of 'Pablo Picasso' is courtesy of Gerry Leonard.

When Leonard and fellow lead guitarist Earl Slick arrived at the studio, it was with their heavy artillery. Utilising his stage gear, Slick recorded the bulk of his solos through an enormous Marshall stack, while using a prototype Pod for the title track; Leonard, although using smaller amps, beefed up his own sound with effects, the Boomerang enabling him to play licks that could, for instance, be flipped around or undergo pitch changes.

"These guys know their equipment so intimately, it's beyond me what they do," says Tony Visconti. "How they interact and interface with the gear is amazing. Like David Torn, Gerry Leonard plays a lot of ambient guitar, while Earl Slick is all-out balls-to-the-wall. He's definitely more in the tradition of guitarist as rock god, although not without a fair degree of sophistication. He came up with some pretty amazing stuff on his own.

"To record them I used the SM57, which is very reliable, and occasionally I'd open up one of the PZMs and try it out. Gerry had an open-back amp that I miked from behind with a Sennheiser 421, because I found that I got more low end by positioning the mic there if that's what was called for. I sometimes also did that with David on his Supro amps, which are open-back too."

No Virtuosity?

Once again displaying his virtuosity, Bowie gave yet another outing to his old Selmer baritone saxophone during the Reality sessions, embellishing the texture of 'Pablo Picasso', 'She'll Drive The Big Car' and 'Try Some, Buy Some'. Not quite as prominent as his sax parts on Heathen, the performances this time around blended into the background as part of a section and were captured with a valve Neumann U47.

Mike Garson, meanwhile, played a Yamaha digital piano that Bowie has owned for many years and which Garson uses on stage. Taking the MIDI files back to LA where he lives, the keyboardist played them through his Yamaha MIDI Grand, producing real piano in a room with a couple of microphones overhead. Once his tech guy had re-recorded these tracks, he then sent Bowie and Visconti a Pro Tools file, thus providing them with a choice between the synthesized Yamaha piano that had been tracked in New York and the real piano produced in LA.

"On 'Bring Me The Disco King' we actually preferred the sampled Yamaha piano, whereas the 'real' piano won out on 'The Loneliest Guy'," Visconti says. "So, we had a mixture in terms of Mike's piano contributions, while David took the lion's share of all the synthesizer parts. He loves his Korg Trinity, he knows it intimately, and he can just dial up sounds at will. When he was writing his songs he made notes of certain sounds that he wanted to use, and he ended up playing most of the sonic landscape parts; the big string parts, choirs and so on. He'd do a little work at home and then we'd refine it in the studio, and sometimes we'd record it direct, not using MIDI at all. Then, at other times, there might be an idea that neither he nor I could play — I'm a guitarist, not a keyboard player, but I could certainly play something into MIDI and make it sound a lot better with some judicious editing.

"We both collaborate on musical ideas. David will immediately ask to me lay down a bass part and just leave me to it, and then he'll end up coaching me, which is great. He'll come up with different variations to what I come up with, and then he'll play the guitar and I'll coach him. It works out really, really well. We're like two band members when we record."

Photo: Eleonora AlbertoBowie concurs: "There's a sense of freedom working with Tony that I rarely find with other producers; a non-judgemental situation where I can just fart about and play quite badly on all manner of instruments, and Tony doesn't laugh! I can't tell you how important it is to feel that free in the studio, and that somebody isn't judging your musical abilities. Often, when I've done something with Tony, it just sounds right. It might not be played perfectly — there's no virtuosity on the keyboards or anything — but there's a certain way that I'll put a B flat into a chord that nobody else would, probably because they've been trained properly, and it just sounds interesting. Well, Tony can spot that, whereas a lot of other producers will say, 'Whoo, that B flat's a bit suspect.' I'll be thinking, 'Ah, shit! No, that sounds good, Mr. Producer!'"

Photo: Eleonora AlbertoBowie concurs: "There's a sense of freedom working with Tony that I rarely find with other producers; a non-judgemental situation where I can just fart about and play quite badly on all manner of instruments, and Tony doesn't laugh! I can't tell you how important it is to feel that free in the studio, and that somebody isn't judging your musical abilities. Often, when I've done something with Tony, it just sounds right. It might not be played perfectly — there's no virtuosity on the keyboards or anything — but there's a certain way that I'll put a B flat into a chord that nobody else would, probably because they've been trained properly, and it just sounds interesting. Well, Tony can spot that, whereas a lot of other producers will say, 'Whoo, that B flat's a bit suspect.' I'll be thinking, 'Ah, shit! No, that sounds good, Mr. Producer!'"

In The Mix

Although perfectly adept with all facets of the recording environment, Bowie trusts the judgement, ears and work methods of his co-producer/engineer, and he is therefore more than happy to leave most sonic considerations up to him while making some suggestions of his own.

"David no longer likes to do anything technical," Visconti confirms. "However, his years of experience when he produced without me — producing Lou Reed and his own albums like Station To Station — have left him with a great knowledge of what can be done in the studio. What's more, he also hasn't forgotten a thing. He'll suddenly just turn around and, referring to a very tight digital delay, he'll say, 'You know that sound you got on my voice on Young Americans? I want that for the chorus.' He's got a good mental picture of how something should sound. Then again, he and I are so close in terms of our tastes that we sometimes don't even have to communicate at all. I'll set up a mix and he'll approve of 95 percent of it: 'I think that's great. Just keep going in that direction.'"

The original intention was to mix on the SSL in Looking Glass Studio A. However, as Visconti had already been doing a lot of his own automation within Logic, he was virtually mixing as he went along, and both he and Bowie were more than satisfied with some of the MCI board mixes that they'd been taking home. The decision was therefore taken to do the mix in Studio B, while a 5.1 version was indeed mixed in Studio A.

"We took out the old-fashioned MCI [Megamix] automation," Visconti explains with regard to the stereo mix. "We bypassed the VCOs and VCAs, so whatever we put through that board came back sounding really pristine, very clear and uncoloured. I was using a lot of plug-ins to get some of the sounds, and they were sounding so good that we eventually said, 'Let's try mixing it on the MCI in Studio B.' That's what happened, and we ended up doing all of the mixes there. Besides plug-ins, I would plug in some external EQs, like Pultecs, as well as Avalons for the vocals and bass guitar. In effect, we were combining two worlds, using a real old board that wasn't meant to produce a high-standard 2003 album, yet attaining some great sounds out of it.

Part of the huge array of outboard in Studio A.Photo: Eleonora Alberto"We had 34 channels on the MCI, so with the drum tracks, for example, I'd put the toms and the ambient mics together, routing them inside of Logic to two channels on the MCI. Therefore, even though I'd sometimes have as many as 12 or 13 drum tracks — what with the tracks from Allaire — they were only coming up on eight channels on the MCI board after being pre-mixed inside of Logic. I also did that with a lot of backup vocals — six, seven or eight of them would come up as a stereo pair on the MCI.

Part of the huge array of outboard in Studio A.Photo: Eleonora Alberto"We had 34 channels on the MCI, so with the drum tracks, for example, I'd put the toms and the ambient mics together, routing them inside of Logic to two channels on the MCI. Therefore, even though I'd sometimes have as many as 12 or 13 drum tracks — what with the tracks from Allaire — they were only coming up on eight channels on the MCI board after being pre-mixed inside of Logic. I also did that with a lot of backup vocals — six, seven or eight of them would come up as a stereo pair on the MCI.

"In order to do the recalls, I had a digital camera which I set to high resolution. I would photograph the board in three or four sections, and then when we'd recall we would bring up each shot in Photoshop and magnify it, and we could actually get a single knob measuring about nine inches in diameter! That way we were able to see precisely where we left the mix, and I can tell you, the results were just as good as any SSL recall."

And For His Next Trick...

Right now, embarking on a world tour that will play to more than a million people in 17 countries over a seven-month period, Bowie isn't even thinking about his next album. However, it's a pretty safe bet that whatever this turns out to be, it will mark yet another change in direction.

"I don't keep changing just for the sake of it, but there is a desire to change, even though probably the subject matter remains much the same from album to album," he says. "I don't think I write about a terribly wide range of subjects. My excitement is in finding a new way of approaching that same subject, and at heart I think that is what most writers do. They have, maybe, only a small basket of subjects that they write about, but they reapproach those subjects differently every time, and that's what I tend to do as a writer. I invariably deal with the same senses of isolation and lack of communication and all these kinds of negatives, and I'll probably deal with them to the end of my life. There'll be certain spiritual questionings and all that, and it won't change very much, because it never has, it appears, from 'Major Tom' to Heathen. It really is all about the same thing, and obviously my big four or five questions are in there somewhere."

So, is he any closer to getting them answered?

"Abs... of course not! One takes these questions to the grave. The human instinct is to always try to make a connection between one fact and another and try to make sense of two different things. I've just made that a writing process."

Temporarily Satisfied

Tony Visconti, meanwhile, admires the man's artistic integrity and originality, as well as his insistence on continuing to develop. "Heathen enjoyed great critical success and sold very well and we could have repeated that formula, but I automatically knew he wouldn't do that, because he never does," declares Visconti, whose schedule throughout the remainder of 2003 takes in projects with the Finn Brothers, Hugh Cornwell and the Manic Street Preachers. "When we did Young Americans, RCA Records begged him to do Young Americans II, but instead he did Low. David does something because he wants to know if he can do it, but once he is able to do something he doesn't want to repeat himself. I love the fact that he's always challenging himself and creating new, vital music."

For his part, empowered by a strong inner sense of quality control, David Bowie isn't as blasé as some artists are about the final product, and neither is he among the eternally dissatisfied. Instead, he professes himself to be "temporarily satisfied at the final mix. Then I probably see ways that we could have reapproached the songs quite soon after that, before getting another sense of satisfaction when we start rehearsing them live as a band, because at that point they start to become a different kind of animal. I mean, the songs on this album are fantastic live — I was so excited about how they feel. They were the first things that we learned when we went into rehearsals, and they are truly going to be great stage songs."

For his part, empowered by a strong inner sense of quality control, David Bowie isn't as blasé as some artists are about the final product, and neither is he among the eternally dissatisfied. Instead, he professes himself to be "temporarily satisfied at the final mix. Then I probably see ways that we could have reapproached the songs quite soon after that, before getting another sense of satisfaction when we start rehearsing them live as a band, because at that point they start to become a different kind of animal. I mean, the songs on this album are fantastic live — I was so excited about how they feel. They were the first things that we learned when we went into rehearsals, and they are truly going to be great stage songs."

And as for those concerts, Bowie points out that the production values serve as a good indicator with regard to how much more confident he now is in terms of his live performances. "The more confident I get, the less and less I use on stage," he explains. "These days I'm just wearing a suit, and that's about it! That's my full theatricality and I'm really enjoying it, especially as an interpreter of songs. I tell you, the thing that's been inspiring for me getting older is that it feels and seems my writing is staying buoyant. It feels strong and the songs have a real resonance, and it makes me very confident now about plunging back and doing old stuff as well. I really steered away from that during the early '90s, because I wasn't at all confident about what I was writing then and I just didn't know if it stood up to the old stuff. So, I kind of cleared the decks just to get back on my feet as a writer and to not feel too much comparison being thrown at myself, even if it was self-inflicted. Now, however, I can take anything from the past and put it alongside what I'm currently doing, and I feel, 'Hey, this is a really good chronological show. It dips into every period and I feel that everything is as strong as the one that it's played against.'"

Although, as previously mentioned, Bowie enjoys releasing albums on an annual basis, current touring commitments mean that there will probably be a longer period before he next enters the recording studio. Still, he's already developing some ideas.

"I might get back into the realm of something even more abstract," he says. "However, I'm not sure and I hate to paint myself into a corner, because I might have a terrific change of mind. I mean, my ability that's helped me a lot is the ability to change horses mid-stream, and I've never seen that as something that's held me back. In fact, I've seen it as a positive thing, and I don't feel as though I'm obliged to stick to my word. Whereas other people might think they have to stand by what they've said, I don't have that problem. It's only f**king art!"

Reality Surrounds You

Ably assisted by Hector Castillo, who had helped him with the surround mix on Heathen, Tony Visconti created the 5.1 version of Reality on the SSL 4048 G-series console in Looking Glass Studio A, immediately after having taken care of the stereo mix in Studio B.

The 5.1 version of Reality was mixed on the SSL G-series desk in Looking Glass Studio A. Photo: Eleonora Alberto

The 5.1 version of Reality was mixed on the SSL G-series desk in Looking Glass Studio A. Photo: Eleonora Alberto

"Because I mixed on the MCI board and did all of my moves in Logic, it was much easier to mix Reality in Studio A as the levels were 90 percent correct for 5.1," says Visconti, who had already mixed 5.1 versions of Bowie's Ziggy Stardust Live and T Rex's Electric Warrior. "It didn't suffice 100 percent, but only minor tweaking was needed to get the stereo mix sounding very, very good in 5.1.

"Having listened to a lot of other people's 5.1 mixes, I find that traditionally they tend to put all of the music in the front and ambience in the back. In some ways that sounds even weaker to me than stereo. The whole approach to 5.1 has been a very skittish one — people are really cautious about what they put in the subwoofer and whether or not they're going to use the centre channel, but I think the rear speakers should have more of a purpose than just ambience.

"So, what I do is take the opportunity to actually make things clearer in 5.1 by assigning some of the keyboards to the rear speakers. On Heathen I put all of the ambient effects in the rear speakers, like the wash of keyboards, and while there wasn't so much of that on Reality, I would still take the keyboards that we had towards the left and place them partially in the front and about 70 percent in the back, left-right. At the same time, I used the centre speaker exclusively for Bowie's voice, and I bled some of that to the left and right front speakers.

"A lot of people don't do this, but if you're working with a rock track I don't see any reason why you shouldn't put the kick drum and bass in all five to six speakers. I do that to various degrees — I favour the front, but you'll still hear them in the rears, and so when you sit in the middle of one of my 5.1 mixes the air everywhere is moving and you feel much more involved. The reason I do this is because low frequencies are non-directional — you can't tell where the bass and kick drum are coming from, you just feel them, and so directionality isn't a problem. If you have all of those speaker cones, I feel they should be used.

"Normally I'll put the snare and the toms and the cymbals in the front left and right speakers. With Heathen and Reality I also had the benefit of Allaire's big room, and so I would always put the drum room mics in the rear, creating the feeling that you're actually in the room itself when it was recorded, and it is an awesome sound. Ironically, when I did Electric Warrior I always made sure I had at least one track of ambience — back in the '60s, my mentor Denny Cordell told me that it would always be useful to keep an open mic in the room, but I don't think he realised how useful this would be in the year 2003 when you're doing a 5.1 mix and you have an ambient mic that gives you a kind of time delay. It makes you go 'Aha, so this was the size of the studio that the band was in.' You get more reality that way."

No pun intended.

"My approach to 5.1 is to be involved, to have instruments wrapped around you rather than in front of you. Rather than putting you in the audience seat I actually put you in the band, and so that's what I did with Reality. Also, I put a slap-back on the vocal in the rear speakers to again create space. Now, that space is not uncommon at a live rock concert — you hear all of that stuff going on behind your head in the theatre — so I skip between the two worlds of true reality and studio recording, which is totally fake anyway. Don't let people tell you that rock studio recordings are the real deal. They're not. You're pumping up the kick drum — if you hear a kick drum in a room, it's a puny little instrument compared to how loud it is on a stereo mix. So, I see 5.1 as an opportunity to further the illusion of vastness and the whole macho rock thing. It's the perfect medium for that."