Veteran guitarist Carlos Santana's 1999 comeback album Supernatural has been a sales phenomenon in the US album charts. Richard Buskin spoke to engineer Glenn Kolotkin, whose association with Santana goes back to his classic albums of the '70s.

It was the early 1980s and automation was a fairly recent innovation within the world of recording. Producer/engineer Glenn Kolotkin was in the studio with co‑producers Ritchie Cordell and Kenny Laguna, remixing a song on an automated system, and after three hours everything sounded perfect... well, almost. Kolotkin, you see, wasn't at all happy with how things were turning out.

"I was the associate producer and I said, 'Look, let me try this another way,' and I pulled all of the patches out and started from scratch. Fifteen minutes later I called them back in to listen to the new mix and what they heard was completely different. They said, 'Yeah, we like that, but we also like what we did.' We had five or six mixes that were all automated, and then we had this other one that didn't resemble anything, so it was suggested that we put the new one in the middle of the others, call the band in and ask them to pick the best one. Well, that was fine with me, and as soon as we got to the 15‑minute mix everyone jumped up and said, 'That's the one!' You know, it wasn't perfect, it was a 15‑minute mix, but it turned out to be one of the biggest records I've ever had; 'I Love Rock & Roll' by Joan Jett and The Blackhearts. It was Number One for seven weeks. Now, if you listen to that record it's certainly not a perfect mix, but the excitement is there, and this would have been ruined if we had worked on it for hours to get it perfect."

"I was the associate producer and I said, 'Look, let me try this another way,' and I pulled all of the patches out and started from scratch. Fifteen minutes later I called them back in to listen to the new mix and what they heard was completely different. They said, 'Yeah, we like that, but we also like what we did.' We had five or six mixes that were all automated, and then we had this other one that didn't resemble anything, so it was suggested that we put the new one in the middle of the others, call the band in and ask them to pick the best one. Well, that was fine with me, and as soon as we got to the 15‑minute mix everyone jumped up and said, 'That's the one!' You know, it wasn't perfect, it was a 15‑minute mix, but it turned out to be one of the biggest records I've ever had; 'I Love Rock & Roll' by Joan Jett and The Blackhearts. It was Number One for seven weeks. Now, if you listen to that record it's certainly not a perfect mix, but the excitement is there, and this would have been ruined if we had worked on it for hours to get it perfect."

The moral to this story? Well, spontaneity can certainly be a large part of the mixing process, and it is spontaneity that has been prevalent in much of Glenn Kolotkin's work throughout the past 35 years, whether he has been behind the console for Janis Joplin, Pete Seeger, Paul Winter, Al Kooper, Barbra Streisand, Taj Mahal, Greg Kihn, Dr Hook & The Medicine Show, Moby Grape, Robert Palmer, Jonathan Richman, The Ramones, Captain Beefheart, Lionel Hampton, Sonny Rollins or, perhaps most notably, Carlos Santana, among many others.

"Years ago we definitely had to be more creative," says Kolotkin. "We had to make decisions. Tracks were always at a premium and we had to be concerned with how we used them, whereas now we never really run out of tracks, and I actually think that music has suffered as a result. We really had to go for performances back then, and there was a certain excitement that came right out of the speakers when the band was playing live. That's something you don't often hear any more. Some people make records a track at a time, but I still like to make live recordings. They're fun. Producers today don't have to make a decision, and so they will change parts, but every time you change a part something will always be lost; some of the spontaneity. It's a slow process of losing that magic. We used to have that all the time, and we wouldn't accept takes back then if they didn't have it."

"Years ago we definitely had to be more creative," says Kolotkin. "We had to make decisions. Tracks were always at a premium and we had to be concerned with how we used them, whereas now we never really run out of tracks, and I actually think that music has suffered as a result. We really had to go for performances back then, and there was a certain excitement that came right out of the speakers when the band was playing live. That's something you don't often hear any more. Some people make records a track at a time, but I still like to make live recordings. They're fun. Producers today don't have to make a decision, and so they will change parts, but every time you change a part something will always be lost; some of the spontaneity. It's a slow process of losing that magic. We used to have that all the time, and we wouldn't accept takes back then if they didn't have it."

In The Army Now

Glenn Kolotkin's first excursions into the world of engineering took place in high school during the late '50s, where he recorded a number of vocal groups using a 78 rpm disc‑cutting machine. When his studying days were over, Kolotkin then went into the US Army, where he ran a radio station, and it was on his return to civilian life in 1965 that he leafed through a copy of the Manhattan Yellow Pages, looked up 'Recording Studios', and landed a job at the first facility listed under that heading: A1 Sound.

Originally the property of Atlantic Records, this four‑track setup was owned by Herb Abramson when Kolotkin started, beginning as a fully fledged engineer. "I never really had any experience assisting," he says. Sessions with rock and blues acts such as Tommy Tucker, The Clovers, The McCoys and Screamin' Jay Hawkins preceded his move from A1 Sound to a two‑track facility on West 57th Street named Nola Penthouse Recording Studios, which focussed on recording jazz. At least, that was the genre which interested its owner, Tommy Nola, and so he handed Kolotkin the rock and roll assignments which he himself had no interest in.

Nevertheless, it was a long‑term stint with Columbia Records that really established Kolotkin's career. In 1967 he remixed part of The Rolling Stones' Their Satanic Majesties Request album in Columbia's Manhattan studio, and followed this up with a remix of Jimi Hendrix's Electric Ladyland. Following more engineering projects in New York, ranging from Moby Grape to Johnny Mathis, Kolotkin relocated to the West Coast, where in 1971 he worked on projects such as Barbra Streisand's Stoney End, The Byrds' Byrdmaniax and Taj Mahal's Happy Just To Be Like I Am, while also recording some of the tracks on Janis Joplin's final album, Pearl. Only about three songs into the Pearl sessions, Kolotkin was on his way again, moving from Los Angeles to San Francisco, where Clive Davis was setting up a new Columbia Records studio to be run by producer Roy Halee. "That was a nice place to work," Kolotkin recalls. "It was like being at an intense little studio with the money of a major record company behind it, and it consisted of a small group of people who were really just interested in making records. It had this kind of independent feel, it wasn't bogged down in all of the union rules that there were in New York and Los Angeles, and Clive really felt strongly about it, so he sent us artists like Dr Hook & The Medicine Show and Carlos Santana."

Love, Devotion And Santana

Over the course of six years Kolotkin engineered numerous Santana albums, including Santana 3, Carlos Santana & Buddy Miles Live, Caravanserai, Love, Devotion and Surrender, Borboletta and Moonflower. That last record was recorded in 1977, and the next year, following Clive Davis' resignation from Columbia Records, Glenn Kolotkin also left the company and went independent. Credits would follow with the likes of The Ramones and Joan Jett, as would a spell on staff at BMG Records, and it would be more than two decades before Kolotkin would once again be reunited in the studio with the Latin‑jazz‑rock‑fusion guitarist. However, when this did happen, it turned out to be for a landmark project.

"I was doing a lot of independent work for BMG when I saw the [Santana] group on television being inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall Of Fame," Kolotkin explains. "I called my wife in to take a look and pointed out all of the members of the group whom I knew very well, and she said, 'Why don't you write Carlos a letter and congratulate him?' So, that's what I did, and he called me back and said, 'Come on out and help me to record my latest album.' That's how I got to work on Supernatural. It was just like old times, although — not having seen each other in around 20 years — it was clear that we were all grown up!

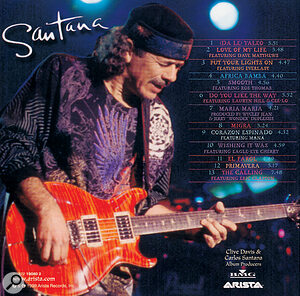

"Carlos told me that he had just signed with Arista Records but that they weren't sure what direction the first record should take or which of the tunes that we worked on would end up on the album. So, I started recording him at The Plant in Sausalito, close to where he lives, and we actually did a lot of recording out there. We probably did 60 or 70 minutes' worth, and in the end three of the tunes that I worked on made it onto the album.

"We'd work for four or five days at a time, 12 hours per session, take maybe three days off while they toured, and then return to the recording — in total we must have worked on about a dozen tunes. In the old days we always knew what would probably end up on the album, but this time we really didn't. When I first heard the album I didn't know which tunes had been used, not least because some of the titles had changed! What's more, some of the recordings had actually been done before Carlos was signed, and I remember working on takes that had originally been recorded at Fantasy Studios in Berkley [California]."

Consequently, the aforementioned trio of Kolotkin‑recorded tracks all boast co‑engineering credits on the multi‑Grammy‑Award‑winning album: '(Da Le) Yaleo' with Mike Couzi, produced by Santana; 'El Farol' with Jeff Poe, John Karpowich, Jim Gaines and Steve Fontano, produced by KC Porter; and 'Primavera' with Jim Scott, Jeff Poe, John Karpowich, Matty Spindel, Jim Gaines, Steve Fontano and Alvaro Villagro, also produced by KC Porter.

Mic Matters

"We recorded 30ips, 24‑track, no‑noise reduction, using a Studer, a 40‑input Neve console, good analogue equipment and a nice selection of microphones," Kolotkin says with regard to sessions at The Plant. "Most of the musicians were set up in the main room, although I had Carlos's guitar amps in an isolation booth, and much of the miking was pretty standard. Basically, I used multiple microphones on Carlos' guitars; Electrovoice RE20s close, Neumann U47s further away, an SM56, U87s. He was playing through an assortment of amplifiers at the same time, and by using multiple microphones I was able to get just the right blend.

"I like to use RE20s on most amplifiers when they're available, because the quality is great and they can really take high levels. They're very directional and they're great for rock & roll. For the drums I used an RE20 on the kick, along with Sennheiser 421s on tom‑toms, AKG C414s as overheads, a Neumann KM84 on the hi‑hat, and a Shure SM50 on the snare. Bass guitar was recorded direct, as well as miked through a cabinet with an SM56. In terms of effects, on this album I didn't use many, whereas in the old days a lot of effects were actually on the tape."

Then And Now

'(Da Le) Yaleo', which opens the Supernatural album, was also one of the first tracks that Glenn Kolotkin recorded when he began participating in sessions at The Plant. Pre‑production was minimal, with the band simply performing a few run‑throughs before the desired take found its way onto tape, and then it was onto another number, with overdubs taking place at a later date.

"It was very different to the way in which we used to record," Kolotkin points out. "What we used to do was have the whole band jamming in the studio, and while this was going on I'd be recording everything 16‑track to two‑inch tape. Afterwards the band would come into the control room and I'd play everything back, and maybe out of the whole tape there would be only 15 or 20 seconds that were really magical, but they would work that into a song. They'd take a riff, perhaps, re‑perform it, hone it down, develop it and eventually it would evolve into a tune. It was amazing. The band would then go on the road and perform the song live, and when they'd come back we might record it from scratch again in order to capture how it had evolved. As a result of working like that the third album took about a year to make.

"Nothing was really written, but there would always be some outside tunes brought into the studio — [drummer] Mike Shrieve was good at doing that — as well as tunes that the group members innovated themselves and worked on together. Things were very exciting back then. There was a loose feel and the whole process was really very creative. Things just evolved and there wasn't any pressure in terms of studio time. It took what it took, whereas now everything is far more disciplined. In the old days we'd work around the musicians' schedules — we'd wait for a musician to get back if he was playing a gig or something — whereas on the new album if somebody wasn't available we'd work with somebody else who was available. Also, Carlos was now directing things quite a bit, whereas in the early days it was more of a group thing and everybody was pitching in."

"Nothing was really written, but there would always be some outside tunes brought into the studio — [drummer] Mike Shrieve was good at doing that — as well as tunes that the group members innovated themselves and worked on together. Things were very exciting back then. There was a loose feel and the whole process was really very creative. Things just evolved and there wasn't any pressure in terms of studio time. It took what it took, whereas now everything is far more disciplined. In the old days we'd work around the musicians' schedules — we'd wait for a musician to get back if he was playing a gig or something — whereas on the new album if somebody wasn't available we'd work with somebody else who was available. Also, Carlos was now directing things quite a bit, whereas in the early days it was more of a group thing and everybody was pitching in."

Not that the musicians' roles are the only ones to have changed during the past 20 or so years, for Santana's '70s‑style sessions were also conducted without one person being clearly allocated the role of producer. "In terms of the group, Mike Shrieve was always very active, but basically it was myself in the control room and the band in the studio," says Kolotkin. "On Supernatural, however, Carlos was mainly directing things and I respected that. You know, Carlos has evolved, he's become the leader, and it's really his band now. None of the material that I worked on resulted from those old‑style jam sessions and, because it was more contrived, it was no longer really a case of making sure that the tape was always rolling so that I wouldn't miss any moments of inspiration. We'd simply go in to record something and do it. In the old days, on the other hand, there would be certain 'happy accidents' — I remember a lot of effects on the third album and on Caravanserai resulting from these.

"A lot of musicians today wouldn't be able to play at all if it wasn't for the technology, but of course that definitely isn't the case with Carlos, and I have to say that there's also never any pressure working with him. He likes to get things the way he envisions them in his head, yet if something isn't done at one session it will be done at another."

Accustomed to mixing as well as recording the albums which he worked on with Santana during the '70s, Glenn Kolotkin was not assigned the former task this time around. Nevertheless, while fellow engineers such as Jim Gaines and Jeff Poe took care of that particular job, Kolotkin still adhered to his usual method of mixing while recording. "I always try to mix as I go along," he says, "So at any given point there's always a very good rough mix to hand. Personally, I don't like to leave anything on the tape that doesn't belong there, because it would drive me crazy to be making choices over things that aren't going to be used and then find out that they have resurfaced at a later date. That happens all of the time now — I mean, recently they've been remixing things for CD which I originally recorded, and when I listen to them there are parts that I don't even recall hearing before. That's because they were meant to be cut out, but the guy who remixed the record found them on the tape and apparently liked them. It's therefore best to eliminate those tracks, because if they're not there they can't come back!"

Neves, Neumanns and NS10s — Kolotkin's "old analogue sound"

Unlike many other producers and engineers, Kolotkin doesn't have a home studio; nor does he carry gear around from session to session. After all, even though he prefers to monitor on NS10s, most of the facilities where he prefers to work — including Sorcerer Sound and Clinton Studios in New York City, as well as The Power Station in New England — carry them, so why bother to invest in his own?

"I know of some engineers who even carry around their own monster cable," he says, "But to tell you the truth, I can never hear the difference. There again, most good studios today have the boxes that produce the phasing effects that I used to create with tape machines, as well as those for echo and so on. A lot of guys carry those sorts of boxes around, but I always try to work at studios that have the equipment I need, and, if not, we can rent it.

"I really do like Neve consoles for their warmth and flexibility, and it seems that most of the studios where I work have them. The Neve is a good tool and you don't hear it, which is nice!

At the same time, I also like really high‑quality microphones, especially vintage microphones, and a lot of the studios where I work have the ones that I like to use. Still, we're in the year 2000 now, and one of the most popular mics — the Neumann U47 — was created in 1947, so where have we got to? We're still using it and you can't deny that it sounds great. It's like the whole business of people trying to get back to the so‑called 'old analogue sound'. Well, you know, that old analogue sound was great, but the only problem was that the tape during those years was no good. Digital, on the other hand, is here, and people complain that it sounds so hard. Recently I've been doing analogue recordings on the new tape which sounds great, and with Dolby SR it's perfect. I mean, no hiss at all, and when it's recorded at 15ips it sounds better to me than when something is recorded directly to digital. Still, many people now like to record analogue and master to digital in order to get that analogue sound, but then I have to ask myself 'Where have we come to?'"