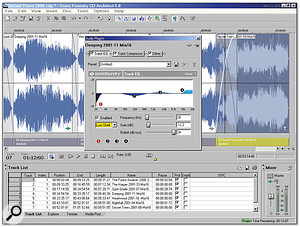

You can assemble an entire album's worth of completed stereo tracks in most modern multitrack audio applications for pre-mastering, although you'll usually still need a separate application to add CD track indices before burning a CD-R.

You can assemble an entire album's worth of completed stereo tracks in most modern multitrack audio applications for pre-mastering, although you'll usually still need a separate application to add CD track indices before burning a CD-R.

There are various ways to translate your rough PC audio mixes into finely honed versions ready to be burned onto a Red Book audio CD. If you have the budget (and it needn't be that expensive if you shop around) you can take advantage of the services of a mastering engineer. The combination of a fresh set of ears, a purpose-built studio with excellent acoustics, and a wide range of expensive equipment designed to get the best from your music should make your various tracks sit better in the context of an album, as well as adding some freshness and vitality. However, many PC musicians still prefer to adopt the DIY approach, pre-mastering their final mixes using PC plug-ins, and then burning their own CD-R that is then sent off to be glass-mastered and replicated.

Mastering Within A Sequencer

It's often possible to use your main PC multitrack sequencer to prepare your stereo masters for burning as a CD-R audio track. For simple projects, you could simply create a song containing only a single stereo audio track, like the Stereo Mastering Setup template in Cubase SX. This approach will work with simple projects where you can drag an entire album's worth of completed stereo songs onto this single track, and it lets you hear all the songs one after the other, which will expose any differences in overall EQ, level, and so on. You're normally so used to hearing each one in isolation that it can be quite a revelation to hear them all together. You'll also be able to adjust the order of the songs and the length of the gaps between them, add non-destructive fades in and out using the automation functions, and in many cases drag songs across each other to create crossfades.

Where this approach falls down is where any plug-in treatments are required, since these generally apply to the entire track. The obvious way to bypass this is to create a separate stereo track for each song, so that you can apply a chain of unique plug-ins to each one. This will also help you adjust relative track levels more easily using a compressor or limiter plug-in — if you've got rock anthems and ballads on the same album, for instance, the ballads may require dropping in overall level to sound correct in context.

Budget Burning Applications

Where most PC multitrack applications need extra help is when it comes to creating the final product, since you still need to add suitable CD track index points and then burn the final CD-R. One honourable exception is Magix's Samplitude 7.1, which has integral Red Book CD-burning functions, and can even burn a CD on the fly from an arrangement, complete with any plug-ins and VST Instrument tracks, without creating an intermediate image file. However, users of applications such as Cool Edit Pro, Cubase VST and SX, Cakewalk Pro Audio and Sonar will all still have to abandon their PC MIDI + Audio sequencer for the next stage.

Once your individual tracks are tweaked to perfection, you can adjust the pauses between them and then burn a Red Book audio CD-R using a variety of low-cost PC applications like Ahead's Nero, which is shown here.Red Book audio CD indexing features should take into account the fact that each track start, track end, or sub-index point must be exactly at a 'frame' boundary, where each frame consists of 588 stereo samples. If the software simply forces the start of each track to the nearest frame you can get unpleasant surprises, particularly when adding track markers during a continuous live set. CDWave (from www.cdwave.com) is one of the cheapest ways to avoid this, and exports a set of correctly split WAV files for you to import into your CD-burning application.

Once your individual tracks are tweaked to perfection, you can adjust the pauses between them and then burn a Red Book audio CD-R using a variety of low-cost PC applications like Ahead's Nero, which is shown here.Red Book audio CD indexing features should take into account the fact that each track start, track end, or sub-index point must be exactly at a 'frame' boundary, where each frame consists of 588 stereo samples. If the software simply forces the start of each track to the nearest frame you can get unpleasant surprises, particularly when adding track markers during a continuous live set. CDWave (from www.cdwave.com) is one of the cheapest ways to avoid this, and exports a set of correctly split WAV files for you to import into your CD-burning application.

I discussed various CD-burning applications for the PC back in SOS January 2003, including Roxio's Easy CD Creator and WinOnCD, Ahead Software's Nero and Feurio, while reader Bill Blackledge also brought the budget Magix Audio Cleaning Lab 3 range to our attention in SOS April 2003.

Many musicians still rely on these simpler applications, even after using a stand-alone stereo editing package to compile their songs into an album, because they are cheap (and often bundled free with new CD-R/W drives), sometimes produce more reliable burns than more advanced music applications, and are so widely used around the world that they get regularly updated to support all the latest drives and their new features, which isn't always the case with more specialist music packages. You may also have more options if you want to create Mixed Mode or CD Extra-format CDs containing both audio and data, so that you can add band screensavers or video clips to provide extra value to your product.

Dedicated pre-mastering and CD-burning applications like CD Architect 5.0 let you apply a different complex chain of plug-ins to each successive track, with the plug-ins only consuming CPU while that track is playing.

Dedicated pre-mastering and CD-burning applications like CD Architect 5.0 let you apply a different complex chain of plug-ins to each successive track, with the plug-ins only consuming CPU while that track is playing.

One potentially serious problem with using a multitrack application for mastering purposes is that in general, enabled plug-ins are active whether audio is being passed through them or not, and continue consuming CPU power even if the track is muted. One of the few PC multitrack applications I've ever come across that avoids this is Samplitude, which lets you apply a chain of plug-ins to an individual Object (part) in a track, so that they only take a CPU overhead while that part is playing. By contrast, if you load up plug-ins in Cubase or Sonar, their total processor overhead remains constant for the time the album is playing.

The reason this may prove troublesome is that, unlike plug-ins designed to be used at the mix, mastering plug-ins can be pretty CPU-intensive. For example, on my Pentium III 1GHz PC a typical EQ bundled with a MIDI + Audio sequencer application might take well under 1 percent CPU, whereas a specialised mastering plug-in like Waves' Linear Phase EQ takes around 14 percent. A suitable chain of plug-ins for mastering purposes can therefore use up the majority of your CPU power for a single track, which is why the developers of applications designed primarily for stereo work nearly always use the same approach as Samplitude, having plug-ins take CPU power only while they are 'active'. This is the case with the Montage function of Steinberg's Wavelab, and with Sonic Foundry's CD Architect 5, and it makes assembling a sequence of finished songs somewhat easier.

Specialist Editing Applications

Dedicated PC stereo audio applications tend to provide far more sophisticated editing functions than the majority of multitrack sequencers, and as mentioned previously, allow all your plug-in processing power to be devoted to each track in turn if necessary. They also provide comprehensive indexing functions that are aware of frame boundary restrictions, and tend to check the final result more thoroughly against the Red Book standard to see if it obeys all the rules, such as those concerning silent frames before tracks, and pauses at the beginning and end of the entire CD.

There are various PC-only applications that specialise in the pre-mastering and CD burning processes. Wavelab 4.0 has an extremely good reputation, while CD Architect 5.0 has plenty of dedicated followers, especially now it's been updated to include to support most modern CD-R/W drives, and is considerably cheaper. However, for those on a budget, Wavelab Essential provides most of the features of its sibling at a similar price point to CD Architect.

If you're anticipating using one of these applications to further treat your mixes after exporting them from a multitrack sequencer then you should always retain the highest available bit depth to avoid rounding errors. If you're using Cubase VST or SX, for instance, exporting in 32-bit format makes the most sense, even if the individual instrument recordings have been made at 16-bit, since once you mix them together more bits are generated. As for sample rate, this depends on your final format, and whether or not you can hear any improvements when using 96kHz or higher rates (see Final Formats box).

Multi-stage Mastering Plug-ins

Some software applications specifically designed for mastering purposes aim to emulate popular hardware 'finaliser' units from companies such as TC Electronic and Drawmer, but are still essentially a chain of plug-ins. Some, like IK Multimedia's T-Racks (originally reviewed in SOS February 2000) are available as stand-alone applications, so you can load in individual tracks, treat them, and then save the result for CD burning in another application. T-Racks includes four sections — an analogue modelled six-band EQ, tube modelled compressor with side-chain, multi-band mastering limiter plus a soft-clipping output stage — and is highly regarded by many users. The new T-Racks plug-in provides the same series of effects, but is designed to be used within any VST or DX-compatible host application, which means that you can launch one instance for each song, to optimise their relative sounds. The plug-ins can also be launched separately, which is handier for general-purpose use, and I'm impressed with their performance.

The same chained approach is used by Izotope's Ozone (reviewed in SOS April 2002), which is PC-only, and suitable for DX-compatible host applications. Ozone consists of six modules, starting with a paragraphic EQ, then a mastering reverb, multi-band dynamics, multi-band harmonic enhancer and multi-band stereo imager, and is completed by a loudness maximiser.

IK Multimedia's T-Racks plug-in provides nearly all the tools you'll need for mastering purposes in one neat chain which can be re-ordered if required.If you've got a DSP card in your PC you may be able to run lots of pre-mastering plug-ins without loading your main processor. For instance, Creamware's Optimaster is included with their SCOPE systems and also runs on most of the other cards such as Pulsar and Luna, and combines a normaliser, multi-band expander, multi-band compressor, and multi-band limiter into one neat package, complete with a Wizard that analyses the dynamics of your songs and sets the controls automatically.

IK Multimedia's T-Racks plug-in provides nearly all the tools you'll need for mastering purposes in one neat chain which can be re-ordered if required.If you've got a DSP card in your PC you may be able to run lots of pre-mastering plug-ins without loading your main processor. For instance, Creamware's Optimaster is included with their SCOPE systems and also runs on most of the other cards such as Pulsar and Luna, and combines a normaliser, multi-band expander, multi-band compressor, and multi-band limiter into one neat package, complete with a Wizard that analyses the dynamics of your songs and sets the controls automatically.

There are also various bundles of separate plug-ins that specialise in mastering functions, one of the best being Waves' Masters Bundle (reviewed in SOS August 2002), which includes Linear Phase Equaliser, the Linear Phase Multi-band compressor, and the L2 Ultramaximiser. Steinberg's Mastering Edition used to provide a good mix of specialised plug-ins, and since its Multi-band Compressor, Spectralizer, and Phase Scope are now effectively bundled with Wavelab 4.0 (see my Wavelab 4 review in SOS May 2002) and Cubase SX now includes Free Filter, users of both probably won't need to buy it — although I still find its Spectrograph sonogram display very useful for examining the spectral content of mixes.

Of course there's nothing to stop you putting together your own chain of plug-ins to achieve the same end, but for the novice in particular, buying a dedicated plug-in chain or mastering bundle can make the process a lot easier, since you have all the tools you need in one package, plus plenty of presets dedicated to mastering to provide some starting points for your own material. You may also get helpful manuals that further explain the various mastering processes. For instance, Izotope have also written two very useful PDF guides covering Mastering With Ozone and Dithering, which you can download free from www.izotope.com.

Final Formats

The most obvious thing to send to a CD mastering house is a 16-bit/44.1kHz Red Book audio CD-R, but there are various other options. Nearly all will still accept DAT tapes, while another option is to burn a CD-ROM containing stereo 24-bit WAV or AIFF files. One big advantage of this approach is that you can also send in your files at sample rates other than 44.1kHz, most popularly at 96kHz, so that the mastering engineer gets the best possible chance of retaining audio quality until the very last stage of the proceedings. You can now even send your WAV fies over secure Internet links direct to some mastering houses.

Sample rates of up to 96kHz are also directly supported by DVD-Audio for surround purposes, which will interest those PC musicians whose multitrack applications already have surround-sound features. However, the only 'project-studio' priced DVD-Audio authoring package I've come across is Minnetonka's Discwelder Steel (reviewed in SOS March 2003), which only supports file formats up to 24-bit/48kHz for 5.1 surround tracks. DVD-A also supports stereo file formats up to 24-bit/192kHz, but I don't know of any PC authoring application that currently supports this.

So, while you may find 24-bit/96kHz recordings capture the last drop of detail, you're still likely to have to downsample in most cases to 44.1kHz before sending off your final product, in which case 88.2kHz might be a more appropriate starting point.

Equalising, Enhancement & Compression

There's no fixed order set in stone for using PC plug-ins for mastering, but a good guideline is to start with any EQ that's needed (and only if it's needed — don't ever pass your final mixes through any plug-in unless you can hear an improvement), followed or replaced by any enhancement or other 'fairy dust' treatments. Then apply a little compression if necessary to pull the mix together, and finish with a limiter to raise overall levels in a transparent way, so that final peak levels are close to 0dBFS.

In general there are two plug-in EQ types available to PC users: surgical and sweetening. The first is primarily designed to alter frequency balance without adding any sound of its own, and includes the popular Waves Q10 Paragraphic, while the ultimate in this category must be the Waves Linear Phase EQ from the Masters Bundle. Pseudo-analogue 'sweetness' can be provided by plug-ins such as the analogue modelled T-Racks EQ and Waves Renaissance EQ, based on classic Pultec designs, while examples of EQs featuring valve 'warmth' include TL Audio's EQ1 and the TC Works Graphic and Parametric EQ, both of which feature the optional Softsat algorithm.

You'll generally get cleaner and more transparent results using specialist mastering EQs than the plug-ins bundled with MIDI + Audio sequencers, particularly at the top end, since they tend to use more bits of precision for a less grainy sound, and often give less interaction between the various bands.

Some mastering engineers avoid enhancers, exciters, stereo imagers, and other 'fairy dust' plug-ins like the plague, but at the project level, this sort of plug-in can prove useful where the final mix lacks that certain something, or where deep bass or extended treble weren't present in the original recording but should have been. Recommended examples include Steinberg's Spectralizer, PSP's Mixbass and Mixtreble, the BBE Sonic Maximiser, Waves' Maxx Bass and their somewhat easier-to-use Renaissance Bass.

As an alternative to these, many compressor plug-ins offer the option to emulate the warm, fat, sound of tape saturation and tube circuitry, which may be more appropriate for overall treatment of your mixes. PSP have gained a great reputation in this area, firstly with the Mix Saturator and Mixpressor of their Mix Pack bundle, but most of all with their Vintage Warmer, a simulation of an analogue-style multi-band compressor. IK Multimedia's T-Racks also includes a tube compressor that allegedly emulates a Fairchild hardware device, while both the TC Powercore and Universal Audio UAD1 sport classic compressor designs that can go to town with DSP, and TC Works provide Softsat on the Compressor/De-esser in their Native Bundle. Perhaps the most widely used compressor plug-ins are still Waves', which include the warm-sounding Renaissance Compressor and the versatile single-band C1, while the more complex C4 Multi-band and Linear Phase Multi-band are more appropriate for transparent mastering.

As has been described in these pages on many occasions, a good starting point for a compressor when mastering is a compression ratio of between 1.1:1 and 1.2:1 and a threshold low enough to give a level reduction of about 6dB on the loudest sections.

To The Limit

Normally the final plug-in in the mastering chain will be some sort of limiter, to raise the overall level of each song in a fairly transparent manner. Once again there are plenty of suitable limiting plug-ins for PC users, the best known being Waves' L1 and L2 Ultramaximisers, Steinberg's Loudness Maximiser, and TC Works' Limiter, while a new contender is Voxengo's mastering limiter, which is claimed to provide a transparent sound to rival these at a much lower price.

Examining the peak and RMS levels of your pre-mastered tracks can provide a good comparison to commercial material. Here, a well-recorded jazz quartet peaks at around -1dB, but has a power level of about -22dB RMS, which indicates a wide dynamic range and unfatiguing sound.After you've assembled your collection of songs and placed them into the desired order, you're bound to find that one of them is louder than all the others. I find it easiest to get this track to the desired final level, generally by adjusting the limiter's threshold until the loudest peaks are just being limited, so that the majority of the track dynamics remain intact while the overall level is maximised. If you don't want to play back the entire track to find these peaks, just use Wavelab's Global Analysis or Sonic Foundry's Statistics tool to automatically find the peak level. If for instance the highest readings for the two stereo channels is -5.5dB, on most material you could set the threshold to about -10dB without unduly compromising dynamic range. Also, make sure you set any Out Ceiling control to a little under 0dBFS, to cope with the D-A converters on some CD players, which react badly to signals that peak at 0dBFS. I use a -0.3dB setting, but some mastering engineers drop as low as -3dB.

Examining the peak and RMS levels of your pre-mastered tracks can provide a good comparison to commercial material. Here, a well-recorded jazz quartet peaks at around -1dB, but has a power level of about -22dB RMS, which indicates a wide dynamic range and unfatiguing sound.After you've assembled your collection of songs and placed them into the desired order, you're bound to find that one of them is louder than all the others. I find it easiest to get this track to the desired final level, generally by adjusting the limiter's threshold until the loudest peaks are just being limited, so that the majority of the track dynamics remain intact while the overall level is maximised. If you don't want to play back the entire track to find these peaks, just use Wavelab's Global Analysis or Sonic Foundry's Statistics tool to automatically find the peak level. If for instance the highest readings for the two stereo channels is -5.5dB, on most material you could set the threshold to about -10dB without unduly compromising dynamic range. Also, make sure you set any Out Ceiling control to a little under 0dBFS, to cope with the D-A converters on some CD players, which react badly to signals that peak at 0dBFS. I use a -0.3dB setting, but some mastering engineers drop as low as -3dB.

Once you've got this first track sounding how you want it you can then adjust the others to fit in with it, using your ears to adjust their relative levels to suit. If you want to give your ears a hand (so to speak), both Sound Forge and Wavelab let you measure the RMS average power of the entire track. Most SOS readers are probably more familiar with using this to measure the background noise levels of their soundcard, but it's also an ideal way to compare average track levels. Classical and jazz music will tend to have a greater dynamic range, and hence a lower RMS average power, with rock and dance at the other end of the range. If your average readings approach -15dB RMS your music will have little 'light and shade', and anything above -10dB RMS will probably be exhausting to listen to for any length of time.

Which Dithering Algorithm?

Although dither noise is at an extremely low level, the various algorithms use different 'shapes' of dither noise. Dithering to 8-bit makes the differences obvious, but many mastering engineers maintain that you can still hear the differences even when dithering to 16-bit. There's even a web site dedicated to getting musician's opinions on this topic. 'The Great Dither Shootout' at www.24-96.net/dither has a variety of downloadable files dithered down from an original 24-bit/44.1kHz master recording to 16-bit/44.1kHz, using a variety of dither algorithms. You can either download the ones of your choice, or take part in a blind shootout poll by downloading a 15MB compilation and choosing the one that sounds best to you.

To Dither Or Not?

Most of us working with 24-bit or 32-bit files will need to convert them to 16-bit/44.1kHz in preparation for burning a Red Book audio CD, and to get the best results you need to add some noise-shaped dither when doing so. I explained the basics of dither in my earlier PC Musician on mastering, as well as explaining a basic technique for hearing it in action on your own music. However, I've recently followed quite a few forum threads concerning the relative merits of various 'flavours' of dither offered by different developers, and this is especially relevant now that many of us have several dither algorithms in our collection.

Nearly all the major PC music applications are bundled with one or more dither algorithms, ranging from the internal ones offered with Cool Edit Pro, Sound Forge and Wavelab, to Apogee's UV22 and UV22HR bundled with Cubase VST, SX and Wavelab and the POW-r range that comes with Logic Audio and Samplitude 7.1. Many plug-ins also come with their own dither options, such as the IDR ones of the Waves L1 and L2 Ultramaximisers.

There are various rules to follow to get best out of the dithering process. The most important is always to dither when changing from a higher to a lower bit depth, to make the most of the available dynamic range of the original file — simply lopping off the bottom eight bits (truncation) when moving from 24-bit to 16-bit will leave your fades sounding very gritty at the bottom end. However, there's no point in adding dither when changing a file from 16-bit to 24-bit, since no information will exist in the extra bits.

Some soundcards provide various dither-related settings, and it's important to use these correctly. For instance, the Lynx range has a Record Dither option that should be enabled whenever you are recording 8-bit or 16-bit files through its 24-bit A-D converters, and whenever the Record volume fader is at any position other than full scale, and a Play Dither option that should likewise be enabled when the Play volume fader is not at full scale (though for best results you should in any case leave such digital level controls at maximum, to make the most of the available dynamic range). On professional cards like these it's handy to have such extra options, but thankfully most soundcard manufacturers try to choose the most appropriate dither settings for you automatically. For instance, drivers for the Echo range used to have an Dither Input option for their digital I/O, which had to be unticked when digitally transferring 16-bit DAT tapes to 16-bit WAV files, since the bit depth remained the same, but the latest drivers do this for you automatically.

Ideally, dithering should be added post-fader, which is the way CD Architect and Wavelab do it. If you want to choose a different option to those available by default you can add an extra plug-in in CD Architect in the Master FX chain, or in Wavelab by going into the Organise Master Section function in the Options menu, and ticking the PM (Post Master) column for the plug-in in question. Similarly, if you want to use the Waves L1 or L2 for raising overall levels in a transparent way, but abandon their IDR dither algorithms in favour of something else, just set the Waves dither options to 24-bit, None, and None respectively, and you can then run your choice of dither plug-in as a separate plug-in.

It's always sensible to accompany any Red Book audio CD-R with a report showing a detailed listing of all track times. Here's one generated by Wavelab 4.0.

It's always sensible to accompany any Red Book audio CD-R with a report showing a detailed listing of all track times. Here's one generated by Wavelab 4.0.

Some experts recommend that you burn both CD-ROMs containing 24-bit audio files and Red Book audio CD-Rs at 2x speed for best results. These days, however, it's getting very difficult to find a CD-R/W drive that can still burn at 1x or 2x speed. Some modern burners may even give more errors when burning at really slow speeds unless they have been specially optimised for this, so you should use a speed in the middle of the available range, ideally in CLV (Constant Linear Velocity) mode to avoid speed changes during the burn. Modern CD blanks tend to be optimised for higher burning speeds anyway, but remember that cheap unbranded blanks can give problems at any burn speed.

Unfortunately, even the fact that your CD-R plays on your hi-fi and various other players doesn't guarantee that it will prove suitable for glass mastering, since audio players are generally designed to cope with lots of errors before they become audible. In the event of your mastering company finding TOC (Table Of Contents) errors on your CD-R, most PC burning applications including CD Architect and Wavelab will let you print out a PQ listing (aka Cue Sheet, Track List or CD Report) that you should send with the CD so they can check what you really intended and possibly build a new TOC. Some CD burners (notably those made by Plextor) also let you check for C2 errors (the second level of error correction) with a suitable software utility, which is reassuring before sending off a CD-R to be mastered.