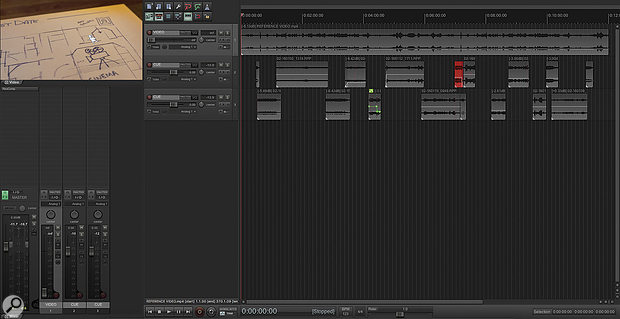

A drastically re-edited drum recording, with its Subproject source open in a secondary tab. Subprojects allow you to perform as much editing to a multitrack recording as you like, while retaining easy access to the underlying session.

A drastically re-edited drum recording, with its Subproject source open in a secondary tab. Subprojects allow you to perform as much editing to a multitrack recording as you like, while retaining easy access to the underlying session.

Reaper 5.11’s new Subprojects facility opens up entirely new ways of working.

Reaper v5.11 introduced a powerful project ‘nesting’ facility called Subprojects. This allows you to use Reaper project files on your timeline just like any other media item. You can even place Subprojects within Subprojects, opening up Inception-like nesting possibilities! This creates new workflow options for album mastering, film composition, sound design, drum editing and more besides.

It’s important to note that Subprojects aren’t real-time nested projects. Instead, each time that you save a Subproject, Reaper performs a project render and saves the result as an RPP-PROX file, alongside the RPP project file. Reaper’s media explorer recognises RPP-PROX files, so you can browse and audition Subprojects just like audio files. This approach enables much better performance and more editing flexibility than a real-time version would. Of course, it means waiting for a render each time you alter and save, but thankfully, there’s an option to defer the render, which can save some time if you’re a habitual Ctrl-S person like I am! Simply right–click on a Subproject tab and tick ‘Defer rendering of subprojects’.

Setting Up A Subproject

Position the edit cursor where you wish to place your Subproject and select New Subproject from the Insert menu. You’ll be asked to specify a save location (a subfolder of the parent project keeps things tidy) and choose a project name. Click Save, and a new empty Subproject will be placed at the cursor position on the selected track. Double-clicking the new Subproject opens it in a new tab. Note the two markers, ‘=START’ and ‘=END’. These set the boundaries of the Subproject in the parent project, and define the area that’s rendered when you close/save the tab.

You can also fold multiple tracks down to create a new Subproject: select the tracks, right-click with your cursor over the track panel, and select ‘Move tracks to new subproject’. In this scenario, the new Subproject is automatically created in the parent project’s folder.

To use an existing project as a Subproject, drag the RPP file from Reaper’s media explorer, the OS X Finder or Windows Explorer. You’ll be asked if you wish to open the project, open it in a new tab, or ‘Insert project as media item’. Select the last. If the project already has an RPP-PROX file it should just appear on the timeline; otherwise, Reaper will open the project in a new tab and render one for you.

Right-clicking on a project tab will open up this menu, which allows you to control how the parent project behaves during Subproject playback.

Right-clicking on a project tab will open up this menu, which allows you to control how the parent project behaves during Subproject playback.

A few options, accessed by right-clicking any project tab, determine how the Subproject interacts with its parent. If you want to hear the Subproject in the context of any other media on the parent, tick the combination of ‘Synchronise any parent projects on playback’ and ‘Run background projects’. If you need to hear your Subproject in isolation, disable ‘Run background projects’. As these options are available in Reaper’s Actions list, you can assign them to a keyboard shortcut or toolbar. You’ll also find actions for ‘Insert new subproject’, ‘Move tracks to subproject’, and ‘Move Items to subproject’, so you can incorporate Subprojects into your macros.

Potential Applications

There are countless possibilities, but here’s a quick roundup of some useful things that I’ve seen users do with Subprojects so far.

Project organisation: Subprojects can be a handy way of keeping things neat and tidy, or for editing large multitrack groups as if they were single media items. You might, for example, nest your multi-mic drum tracks into a Subproject, then edit it to create a new beat, while retaining easy access to the unedited source recording.

Sound design: Subprojects are a great way for a sound designer to build ‘compound’ sounds, by which I mean various clips that are combined in some way to create a new sound. Usually, you’d either layer these over several tracks in your main project, or create them in a separate project, render them to an audio file, and use that rendered version in your project. Combining them in a Subproject means you can use them within a scene just like any other media, but still dive in and make tweaks and changes if required. Any changes will then dynamically update throughout the project, wherever they occur.

The same approach is also useful when doing early work with draft sounds, as these can later be updated en masse. Say, for example, that you’re laying out the first draft of the sound for a big sci-fi battle for a film or a game cut scene. You’re not quite sure what you want the laser-gun to sound like, but you need a starting point. Rather than lay in a draft WAV file, you nest that WAV within a Subproject. Later on, once you have the whole scene laid out, you can edit or replace the contents of the Subproject, and every instance of it in the scene will be updated dynamically to reflect that change.

Album mastering: Once the recording and mixing is complete, you can easily import each of your song mixes as a Subproject in your new master project, in order to apply mastering effects, shuffle the running order around, and perform any crossfades or other transitions between tracks before generating final files. Subprojects let you do all of this, while giving you the flexibility to jump quickly and easily back into the song projects, should you need to make that one last tiny mix tweak. It’s the perfectionist’s dream — but quite possibly the procrastinator’s nightmare too, so be careful!

Music for picture: There are two main schools of thought when it comes to the workflow for music for picture. One entails the use of a single project for the entire film. This provides a helpful ‘big picture’ view of your work, and allows you quickly to move around between sections of the film. But if you’re required to make tempo or time-signature revisions, it can become very difficult to ensure that your existing work further down the timeline doesn’t get corrupted. Naturally, composers have developed a few tricks to work around this, but they’re pretty fiddly.

This is a scoring session for a 12-minute TV episode. Each media item represents an entire multitrack MIDI project, each with several dozen tracks of virtual instruments inside.

This is a scoring session for a 12-minute TV episode. Each media item represents an entire multitrack MIDI project, each with several dozen tracks of virtual instruments inside.

The other approach is to split the film up into multiple cues and devote a new project to each. This lets you run weird and wonderful time signatures in each cue, and means any changes you might make to one cue are unable to have a detrimental impact on any of the other cues in the film. The down side to this approach is that you don’t have an easy way to play through the film as a whole, check transitions between cues, or generate a ‘whole score’ audio mixdown or preview. Proponents of this approach often bounce their cues and re-import them to a separate ‘master’ project, or even mix in real time to a second computer.

Reaper’s Subprojects allow the majority of the benefits from both approaches, by setting up a master project to contain the entire film, but composing each cue inside a Subproject. This provides a ‘whole film’ view, where individual cues can be accessed quickly with a double click, and then edited. And, since we’re dealing with audio, any time-signature or tempo changes within a cue Subproject will remain completely independent of their neighbours, just like with the project-per-cue approach.

Conclusion

It’s still very early days for Subprojects in Reaper, and there’s already a raft of feature requests being discussed by the user base. But even now, it’s a very powerful tool for anyone willing to get in there and figure out how to make it work for them. Hopefully this column has provided a few ideas to get you started.

Video Demos

I’ve prepared four quick screencasts that demonstrate in more detail some of the approaches described in this article.