We continue our insider's guide to remixing with some practical tips on the creative decisions that will underpin your remix.

Last month, I looked at the world of the remixer from a 'business' point of view, so now I want to explore the creative decisions that underpin a remix. I'll avoid being too genre‑specific, but where decisions might vary according to the genre, I'll try to differentiate between them.

Remix With What?

Possibly the greatest influencing factor in deciding which way to progress with a remix is the actual 'parts' given to you by the record label, and by far the greatest number of remixes are based purely on using the vocals from the original track. This seems to be pretty much standard practice these days, and probably for good reason, too: most remixers will want to put as much of their own sound into the remix as possible, and even if they were given the full multitrack recording, they'd choose to use only the vocal. There are times, though, when you're given other options.

I've recently worked on two remixes that couldn't have been more different: one for Girls Aloud, and the other for Pussycat Dolls. For the Girls Aloud remix we were sent the full 'stems'. Stems, for those of you who are unfamiliar with the term, are groups of instruments mixed together. For example, there may be three guitar parts in a track, but rather than give you every single guitar part separately, you're given the guitar stem, which is simply all of the guitar parts mixed together and recorded as a single (usually stereo and with effects included) track. This doesn't give you absolute flexibility, but it does allow you to manipulate the groups of sounds that are present on the original recording. For remixers, the track will often be separated into the following stems:

- Kick drum

- Other drums

- 'Effects'

- Bass

- Guitars

- Keyboards (sometimes further separated into pads, leads, arpeggios, and so on).

- Lead vocal

- Backing vocals

Working with stems allows you to use, say, the guitars and basses from the original (as well as the vocals), while mixing in your own sounds. In fact, for Girls Aloud, I used plenty of the stems because I wanted to keep quite a lot of the original track in the remix.

It doesn't always work that way, though, and the Pussycat Dolls remix is an example from the other end of the spectrum. For various reasons, all we were given was the original master recording. That's right... exactly what was being played on the radio! Based on my original definition of a remix, it would seem quite difficult to do anything in this case, because there's nothing at all that you can truly subtract from the original; you're forced to only add things. But when the recording is sonically full and complete you might be wondering what you can possibly add. There are things that you can do, but your choices are much more limited, because you have to make choices that are 100 percent sympathetic with the original track. It's not something that you're likely to have to do that often, but it does happen.

Decisions, Decisions...

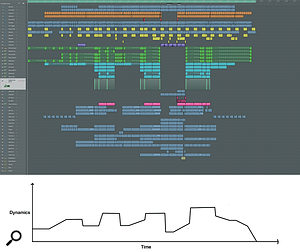

These screenshots are taken from two of Simon Langford's commercial remixes. Notice that although the two vary, one has a 'ramp' intro, while the other has a steady flat intro. However, both have a cyclical build‑and‑drop musical dynamic, which grows as the track progresses.

These screenshots are taken from two of Simon Langford's commercial remixes. Notice that although the two vary, one has a 'ramp' intro, while the other has a steady flat intro. However, both have a cyclical build‑and‑drop musical dynamic, which grows as the track progresses.

Let's concentrate, however, on what you're likely to be faced with the vast majority of the time, and the kind of decisions that you'll find yourself making once you have the remix parts. If you choose to use (or are only given) the vocals, the first choice to make is the overall genre of your remix. In part, this decision will already have been made for you: if you've been commissioned to do a remix, the chances are that it will be because somebody has listened to your showreel and thought that what you are doing is right for the track; and even more often you'll be given some kind of brief by the label or manager. But, even considering all of that, there's still room for flexibility.

Probably the first thing to do is to work out the key and tempo of the original track, and consider whether you might want to speed up or slow down the vocal. For house remixes at around 128bpm, there comes a point with the source tempo where it is in a difficult range, and this presents you with your first serious creative choice: around the mid-90s, you either have to speed it up to 128bpm or slow it down to 64bpm.

There are a lot of factors in this decision, some technical and some artistic, so let's take a look at both of those. If you're presented with an 'unfriendly' bpm, one of the first things you must consider is the vocalist. Some vocalists have a very pronounced vibrato on their voice, and if this is the case, speeding the vocal up by close on 30 percent (for tempos in the mid-90s to mid-120s) will result in a definite 'chipmunk' quality. You'll learn very early on in your remixing career that all vocalists hate that effect! Which means you have no choice but to slow it down... right? Wrong: if you slow a vocal down by 30 percent, the vocalist will sound half asleep, and you'll find yourself reminiscing about the swimming‑in‑the‑toilet scene from Trainspotting.

So if you can't speed it up, and you can't slow it down, what do you do? Your approach depends on the song. If it's rhythmically pretty bouncy, you might be able to slow the vocal down — because it will still have some pace to it — but if you're dealing with more of a ballad-style vocal, the only choice is to speed it up. Otherwise, the combination of long, legato notes and slowing the vocal down will give you real trouble making the vocal feel like a part of the remix.

After you've made this decision, you need to decide on the key of your remix. Normally, you'll stick to the original key, because there's little (but not nothing!) you can do to change it. The one change you can make easily is from a major key to a 'relative minor' key (or vice versa). This is an important decision, because it gives you the power to completely change the feel of the track. Making such a change can add an element of 'coolness' to an otherwise very 'up' track, and can similarly lift an otherwise sombre tune. But, as I mentioned before, you must be sympathetic to what the artist themselves and the record label want. So with this in mind you really need to listen: listen to the song, listen to the melodies and listen to the lyrics themselves. Try to figure out what the key emotion of the track is, and then build on that when you're crafting the remix. Working in this way won't necessarily change the technical side of what you do, but it can help you to develop remixes that feel complete, and where the vocals feel like they're a part of the remix, rather than just being placed on top.

First Things First

From this point on, your musical decisions will be dictated largely by the genre in which you work. Trance music and all of its derivatives generally have quite melodic, even epic chord structures, many of which seem almost orchestral or classical in structure. The music is often based around quite long, legato chord movements, offset by driving arpeggios, and this sort of music often works better with vocals that are more legato and 'floaty'. That's not so say that you can't work a more rhythmic and punctuated vocal into the trance genre — far from it — but you'll have to be subtle and careful to make it convincing. The opposite is probably true of house music, which is more groove‑based. The drum and percussion grooves, and the (often) more syncopated and offbeat basslines, lend themselves to more rhythmically interesting and complex vocals. Again, though, having a more ballad‑like vocal doesn't prevent you from doing a house remix: you just have to be careful how you work with it.

The seemingly common denominator in nearly all dance music is the linearity of it. Most extended remixes start off, for the first minute or more, by simply building the layers of drums and percussion and then bringing in a simplified version of the main groove of the song. Often this will be a bassline that loops around one note or chord of the main groove, and there are a couple of reasons for this. The main one, naturally, is to help the DJ: when a DJ is mixing the tracks together at a club they'll play the main body of the track in its entirety and then, at a certain point, begin to mix into the next record. At this point, musically complex things going on will mean that it's much harder to make the mix smooth, so stripping the end of the track back to something more basic and having the beginning of the next record quite simple gives the DJ a good chance of being able to mix the records together without the result sounding like a shoe in a tumble dryer!

You start off simply, and gradually build up the dynamics and musical complexity of the track to the point where the song itself starts 'properly'. In fact, I often start with the most musically complex part of the track (often the chorus), getting that sounding full, and pretty much as I want it to, and then work backwards into the verses (and bridge, if there is one) by stripping away some elements and, if necessary, changing or simplifying the chord structure. From that point I'll step backwards again into the intro/ending part of the track, where things are simplified even further.

Mental Breakdown

Try to get out to clubs that play music in your chosen genre: listen for interesting features in the tracks being played, but remember also to watch for the all important reaction on the dance floor.

Try to get out to clubs that play music in your chosen genre: listen for interesting features in the tracks being played, but remember also to watch for the all important reaction on the dance floor.

Having done this, I'll turn my attention to the 'breakdown'. There are so many ways to approach this that it would probably fill the magazine if I were to describe them all — but if you've made it this far into the article, the chances are that you've been to clubs before and already know exactly what I am talking about: effects rises, creative filtering, extended snare‑drum rolls, and all those other great little gems that litter dance remixes. But you can still be creative.

Sometimes I'll develop quite a long build up using all of the above elements and then, right at the end, just when you expect the music to come crashing back in, do something as simple as just muting everything for a bar, or even two, and allowing the reverb or delay tails to carry things over before crashing back into the full chorus. This can be a phenomenally effective trick. See what works for you, but as a rule, if you're listening to it in your studio at socially acceptable levels, and it can make you feel that chill running up your spine, it's probably safe to say that it will have the same or even more of an effect at 120 or more decibels in a hot, steamy club full of (often intoxicated) punters.

Another way to create interest is to introduce an extra musical part in the last chorus: something new that hasn't been heard in the track before. It doesn't have to be brash, loud or complex: sometimes even the smallest extra musical line can give a subtle lift just when it's needed.

I'd suggest that you don't stress too much about all this, though, because you're probably a better judge of what feels right than most. During the course of working on a remix, you'll be listening far more critically and attentively, and for much longer periods, than somebody listening to the track in a club. If you can listen back to the track and feel that lift at the end, after however many hours of intensive listening to the track, then it's probably fine. Not stressing doesn't mean lax, though, and it's always wise, assuming you have the time, to listen back the next day, having rested your ears, to make sure it still sounds and feels the same.

Sound Judgement

The sounds that you choose to use in your remix will again be dictated largely by the genre. As much as I hate to admit it, and as much as I sometimes despair at the extent of pigeonholing that goes on in this industry, there's a lot of separation between genres, and it's hard to decide whether to be flexible and work across a few different genres, or whether to work more specifically in one. There are pros and cons to both approaches, but it's a choice that you have to make quite early on in your career.

Being more flexible may offer the possibility of getting more work, but it comes at the cost of finding yourself a niche. On the other hand, focusing too narrowly on a particular sound can limit both the amount of work you get, and the longevity of your career — because building a reputation takes time, and by the time you've mastered a genre, it may already be past its prime.

If you have the means to be a 'true' artist and don't need to be commercially successful, then I'm happy for you — but the reality is that most people don't have those means. So use your best judgement, and think carefully about what you want to do. Remember that it's all about balance: balancing what you ideally want to do against what will allow you to be commercially successful — which can be a hard art to master!

When you start going through the sounds available to you, there are bound to be some that you listen to in isolation which sound so big, epic and full that it makes your head spin. Usually, if you try using one of these in a remix you'll soon discover that it swamps everything else — and you'll take it out again soon enough. So rule number one is to always listen to the sounds in context. Sometimes EQ'ing a sound will help it to work better, and there have been numerous articles in SOS about 'bracketing' (using high‑ and low‑pass filters to restrict a sound's frequency range) to help sit sounds in the mix. I can't stress enough how important that can be.

I've actually made some of the most difficult 'sound choice' decisions while I haven't been concentrating on the mix. So it's worth trying to do something else while you're listening to your work: answer some emails, update your MySpace page, read a paper... anything that takes your focus off the music. If you're focused on deciding whether or not a hi‑hat sounds right, your ears and brain will filter out a lot of other sounds. Focus on something other than that sound (other than the track as a whole) and it can become clear to you straight away what you need to do.

Some genres seem to be dominated by certain sounds. Trance music in the late '90s, for example, was fundamentally based on the 'Super Saw' waveform of the Roland JP8000. In fact, it almost got to the point where it couldn't really be trance unless you had that sound! But this doesn't mean you should be afraid to try things which seem to be out of genre. If you're lucky, you could stumble upon a new combination of sounds and a new sub‑genre that becomes the next big thing. In short, if the sounds fit with each other, and they fit with the song, nobody can tell you that they're right or wrong. Choose them wisely, and make sure that you're not simply overwhelming the ear with the combined noise of 1000 plug‑ins, and you should be fine.

Making The Arrangements

With the sounds chosen, the musical parts worked out, and a rough balance of levels and EQ set, where do you go next? I touched on this earlier, when I talked about the use of the intro and outro sections of the remix, but after we reach the main body of the song there are other factors to consider. Given that most radio edits last about three to three‑and‑a‑half minutes, and that an average club remix will be between seven and eight minutes long, you have to decide how and where to insert that extra time, and how to fill it. For example, assume we have an original track of three minutes long, a remix that we want to be around eight minutes long, and a combined intro/outro length of 2m30s or so. We'll need to create an extra 2m30s within the main body of the remix.

Most club mixes tend to work in sections of eight (sometimes even 16) bars, and many other genres work in this way too. Occasionally there will be an extra bar inserted, or a bar dropped from the original track, and you'll need to allow for this, but normally pretty much any modern song will slot into that framework. Here are a few pointers to get you started.

1. Radio Edits: Most radio edits tend to have few (if any) sections that are just music, with no vocals, and most remixes will sound a little overwhelming if there is no break in the vocals. This means that you can easily 'buy time' by inserting instrumental sections of eight or 16 bars after the chorus and before the following verse.

2. Breakdowns: The breakdown is another good place to insert time, but if this section goes on for too long, you'll lose the momentum that you worked so hard to build. One minute or so is a good length to aim for, perhaps even 1m30s if you can sustain the interest. There are, of course, exceptions to the rule: check out the Extended mix of Size 9's 'Are You There?' to see just how much tension you can build in a breakdown without the listener losing interest.

3. Remix To Length: The final chorus after the breakdown can often be repeated (if it wasn't already in the original), or, as an alternative, you can come out of the breakdown into an instrumental version of the chorus for the prerequisite eight or 16 bars before repeating again, this time with vocals.

By now, you'll be approaching the required length, and the basis of the remix will be mapped out. A good rule for a club remix is that the musical (not sonic) dynamics should follow a sort of 'ramp wave', because the repeated build‑and‑then‑drop, build‑and‑then‑drop (but always on an upward trend: see graphics on page 34) keeps the interest of the clubbers, and helps you build up to the moment when the last chorus of the song comes in and everyone goes crazy.

The Third Ear

The one final decision to make is when not to make your decisions! As with any mixing job, after a whole day of listening to and working on a remix your ears become accustomed to the material, and I therefore never make any critical decision at the end of a working day. I tend to use my mornings to make technical decisions and the later part of the day to make creative ones. With fresh ears, you're much more likely to pick up imbalances in levels and EQ, and other technical issues, whereas if you're working out chord sequences or a new bassline, you can still at least throw some ideas in to see how they work, even if your ears can't detect that the EQ isn't quite right. But that's my preference: you need to find out what works best for you.

Writing about fresh ears has reminded me of the most critical piece of studio equipment that you can own: a friend whose ears and opinions you trust! We'd all love to believe that we know exactly what's right and when a mix is perfect, but the truth is that anyone can get overly attached to a piece of work, and end up overdoing it. To avoid this, I have a couple of friends to whom I'll always play things and get their opinion, but not so much on the musical side of things: more on the technical, and on the arrangement and 'flow' of the track as a whole. It's worth mentioning that these people are not all musos, either. Often I'll play things to friends that I work with on projects, and often tracks that are not in a genre that they like because they won't then get caught up in listening to it and enjoying it (if anything, they'll be more critical). You need to be pretty strong to be able to constantly hear "yeah it sounds good... but it's not really my thing”, and you need to remember exactly why you asked them to listen to it. But if I play things to friends who have no technical knowledge at all, I know that they won't suggest boosting the top end on the hats by a couple of dB: they'll give me an overall picture of how it sounds and feels. Which is what I need. Again, I don't expect to always hear good news: you need to be prepared to listen to other people's opinions if you're to grow as a producer/remixer.

Rules Are There To Be Broken

Having read back all I've written so far, I'm about to negate it all by reaffirming the only real remixing rule: that rules are there to be broken. Everybody will approach a remix differently and there's no single formula for success. Listen to successful remixes, and take notes. You'll soon see that a lot of them tend to follow the same patterns of arrangement, and tend to use the same kind of 'tricks'. This isn't plagiarism (usually!), it's simply the application of a formula that works. Even better, though, is to go out to a club that plays the kind of music that you intend to make, and not only listen to the tracks, but look at the effects that certain parts of the tracks have on the crowd.

Finally, remember that you never stop learning. So try to read the articles in SOS, even those that are superficially not relevant to the genre of music that you make. I've learned an awful lot of what I know, and have acquired a lot of the skills that I have, through reading articles on producing and recording bands, and applying the techniques to electronic music production. Often it doesn't have quite the same effect, but it's certainly something different to add to your remixing toolbox. And there will almost certainly come a time when it's exactly what you need!

About The Author

Simon Langford is a professional songwriter, producer and remixer who, as part of Soul Seekerz, has worked for some of the biggest names in pop music, including Robbie Williams, Rihanna, Sugababes, The Ting Tings and many more.