This often-overlooked orchestral family holds the key to a wide range of exciting tonal colours.

It’s a much remarked fact that most of today’s trailer music and ‘epic’ arrangements are dominated by an identical menu of pounding percussion, blasting brass, soaring strings and cataclysmic choirs. What’s missing? The answer is woodwinds. Despite being a long-established orchestral fixture, the woodwind family is often overlooked in contemporary scores, probably because its instruments tend to be quieter and more subtle (and therefore less able to compete with histrionic voice-overs and explosive sound effects) than other, more iconoclastic and attention-grabbing sonorities.

It would be a great pity if woodwinds were to vanish altogether from sample-based orchestrations, since they can produce a wonderful range of timbres. That said, this particular family doesn’t rub along together quite as smoothly as others. Unlike the strings and brass, a woodwind section’s sound is not homogenous; its principal instruments sound very different from each other, so in order to write effective woodwind parts, composers need to develop an understanding of their particular tonal qualities.

Happily, this knowledge is no longer the exclusive preserve of the classical music world. Due to the digital revolution, woodwinds can be seen in action in countless instructive online clips, and if you want hands-on access to their performances, today’s high-quality sample libraries provide it. For a self-taught musician like myself, the latter development has proved invaluable: due to my sheltered upbringing I’ve never encountered a heckelphone in real life, but having acquainted myself with a good sampled version, I now feel confident to use it in a score when the occasion demands it. (Details of this rare instrument appear below.)

Main Instruments

Though woodwinds come in a bewildering array of shapes and sizes, novice arrangers would do well to focus on four main instruments — flute, clarinet, oboe and bassoon. Each has its own distinctive tone: the flute has a sweet, clear, pure and simple sound with a hint of breathiness in the low register. This lends a vulnerable, voice-like quality to quiet, intimate and lyrical melody lines, but when played loudly in the higher register the instrument takes on a bright cutting edge, enabling it to deliver clearly-defined rhythmic phrases.

Clarinets are the most recent addition to the woodwind family, having been integrated into the orchestra in the second half of the 18th Century. (I presume that’s enough time for notoriously conservative classical audiences to have accepted this upstart newcomer.) Blessed with a beautifully smooth, rounded tone and a huge dynamic range, the clarinet sounds dark, mellow and somewhat menacing in its low notes and brilliantly incisive in the upper register. Such tonal versatility marks it out as a popular all-round woodwind which works particularly well for expressive melodies.

In a radical contrast to the mellifluous flutes and clarinets, oboes sound angular, biting, exotic, and if played loudly in their lowest octave, almost ‘quacky’. While its clear, penetrating timbre sometimes makes it hard to blend with other instruments, the oboe comes into its own in soloistic lines. Its assertive tone has also earned the instrument the responsibility of sounding the ‘A’ note that orchestras tune up to. Since woodwind pitch is affected by room temperature, some orchestras now opt to use an electronic tuner instead — however, according to one source, it’s the oboist’s job to turn the device on and off!

Completing the quartet of principal woodwinds is the bassoon, a magnificently idiosyncratic double-reed instrument. Its distinguishing visual features are a long, doubled-up pipe and curved metal ‘crook’ tube which holds the reed. The bassoon sounds plaintive, dignified and somewhat reflective, but also has a droll, humorous side described by composer Rimsky-Korsakov as “an atmosphere of senile mockery”. While that’s going a bit too far, the bassoon is often used for comedic purposes. On a more serious note, its deep pitch and full, steadfast tone provides a great foundation for woodwind chords, and it can also deliver a poignant melody line in the higher register.

Supplementary Instruments

Each of the four main woodwinds has a set of related instruments which extend the pitch range and provide additional tonal colour. In the orchestra, concert flutes are traditionally augmented by the piccolo, a small flute pitched an octave higher, which despite its diminutive stature can easily make itself heard above the loudest fortissimo racket. You’ll also occasionally find an alto flute adding a sultry low register to the overall flute range, while the rare, exotic-sounding and ultra-breathy tones of the bass flute extend the flute family’s range down to C3, an octave lower than the concert flute’s bottom note of C4 (Middle C).

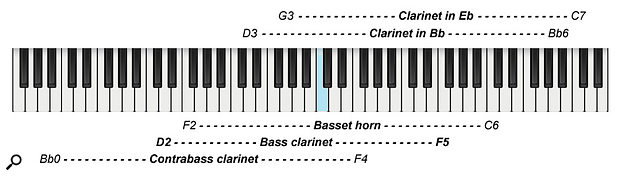

Diagram 1: The long and short of it — (L-R) Average-height male human, contrabass clarinet (approximately nine feet long, bottom note Bb0), piccolo (approximately 13 inches long, top note C8).In a similar vein, the range of the Bb clarinet (the most common model) is topped by the smaller Eb clarinet, a louder, bright-sounding and nimble instrument which is sometimes called the piccolo clarinet. For lower-pitched lines, there’s the fabulous bass clarinet — prized for its plush ‘dark velvet’ tone, it’s often used as an alternative to the bassoon for woodwind bass parts. Though it’s not a standard orchestral woodwind, orchestral sample library connoisseurs may also encounter the mellow-sounding basset horn, a clarinet family member dating from around 1760 which is still made today.

Diagram 1: The long and short of it — (L-R) Average-height male human, contrabass clarinet (approximately nine feet long, bottom note Bb0), piccolo (approximately 13 inches long, top note C8).In a similar vein, the range of the Bb clarinet (the most common model) is topped by the smaller Eb clarinet, a louder, bright-sounding and nimble instrument which is sometimes called the piccolo clarinet. For lower-pitched lines, there’s the fabulous bass clarinet — prized for its plush ‘dark velvet’ tone, it’s often used as an alternative to the bassoon for woodwind bass parts. Though it’s not a standard orchestral woodwind, orchestral sample library connoisseurs may also encounter the mellow-sounding basset horn, a clarinet family member dating from around 1760 which is still made today.

The clarinet also boasts a gigantic sub-bass relative called the contrabass clarinet, a huge, tremendously sonorous beast which stands nearly nine feet tall and descends to the subterranean depth of Bb0, which if we discount piano and organ, is effectively the bottom note of the orchestra. Another instrument that can play that low is the contrabassoon, also known as the double bassoon: its dark, heavy, serious tone is great for bass lines, and the intense, fruity buzz of its bottom notes will raise a smile if played in a light staccato style, or if blasted out at high volume, rattle the windows like the Close Encounters Of The Third Kind’s Mothership.

Returning to more melodic realms, the oboe’s constant orchestral companion is the lower-pitched cor anglais, also known as the English horn, which (as its players like to remind us), is neither English nor a horn — in fact, it’s technically an alto oboe. The rich, dreamy tone of this lovely, sad-sounding woodwind is often heard in long, evocative solo melodies. For the sake of completeness, I should also mention the oboe d’amore (its lovey-dovey name deriving from its warm, lyrical sound), and the bass oboe, which, if called upon, can provide deep, full-sounding bass lines and also deliver expressive solo lines. Neither is commonly used in the orchestra, though they do crop up in some sample libraries.

The latter instrument should not be confused with the slightly larger heckelphone, a type of powerful, sonorous fat-toned bass oboe created in 1904 by the German bassoon-maker William Heckel. Only 165 were ever made, and in 1979 it was said only three existed here in Britain; the instrument is now made exclusively to order (allegedly at exorbitantly high prices), so if you see one going cheap in a car boot sale, snap it up.

You can see and hear many of these woodwinds demonstrated at www.philharmonia.co.uk/explore/instruments (scroll down to ‘Woodwind’, then click on the instrument in question). Vienna Symphonic Library’s Instrumentology pages also feature detailed information and audio examples of the main woodwind instruments: to hear the samples, go to www.vsl.co.at/en/Instrumentology/Woodwinds, click on the instrument name, then select ‘Range’.

Instrument Ranges

Diagrams 2 to 5 show the ranges of the flute, clarinet, oboe and bassoon families as featured in contemporary orchestral sample libraries. Please note that the uppermost notes shown may not be easily achieved by a real player — it’s one thing to squeeze out a usable, squeaky, painfully high top note after a dozen attempts in a sampling session, another thing to reliably nail it in a live performance!

Diagram 2: Ranges of the flute family (Middle C marked in blue).

Diagram 2: Ranges of the flute family (Middle C marked in blue). Diagram 3: The clarinet family’s range covers the whole orchestral spectrum.

Diagram 3: The clarinet family’s range covers the whole orchestral spectrum.

The same caveat applies to the woodwinds’ low range: a standard concert flute’s bottom note is Middle C (C4), but some instruments have an extra key which allows them to play a semitone lower (B3), while a few sample libraries extend the range further by stretching the bottom note down to a Bb3. There’s nothing wrong with that: if you like the sound of a sampled flute playing a low Bb, go ahead and use it, but don’t assume that a real player will be able to produce that note!

Diagram 4: The playing ranges of the oboe family.

Diagram 4: The playing ranges of the oboe family.

When considering instrument ranges it’s important to have a grasp of what their pitches actually sound like in real life, in order that you can write parts in the correct octave. Since synth patches’ pitch ranges are not standardised, the only reliable reference is an acoustic source. On a piano, the note of Middle C (marked in blue in the diagrams) can be found near the centre of the keyboard — its numerical name of C4 derives from it being the fourth C note from the left on an 88-key concert grand. Middle C can also be reliably twanged on a standard six-string guitar (assuming its owner has tuned it recently) by playing the first fret of the second highest string (aka the ‘B string’).

Diagram 5: Bassoon playing ranges.

Diagram 5: Bassoon playing ranges.

Woodwind Sections

The standard woodwind line-up for most symphony orchestras is three flutes, three clarinets, three oboes and three bassoons, with the third player in each group doubling on (respectively) piccolo, bass clarinet, cor anglais and contrabassoon. Other auxiliary instruments (such as Eb clarinet) can be added or substituted, depending on the score’s requirements. Reflecting this triple-woodwind convention, the first wave of orchestral woodwind sample libraries, spearheaded by Miroslav Vitous’ seminal Symphonic Orchestra Samples in 1993, supplied both solo instruments and three-player ensembles playing unison notes.

Though a very welcome addition, the inclusion of woodwind trios started a debate which has rumbled on to this day. Here’s the rub: though they can be coaxed into uttering two or more pitches simultaneously (an avant-garde playing style called ‘multiphonics’), woodwinds are essentially monophonic instruments — in real life, this means if you want a three-note woodwind chord, you have to use three players. Is it therefore bad practice to play a three-note chord on a three-flutes patch, thereby theoretically creating the sound of nine players?

The first thing to say is that nine flute players moving air in a room sounds very different from the effect of three layered samples. Beyond that, I think the answer depends on one’s musical goals: if you’re creating a mock-up with a view to replacing the samples with live players, it makes sense to stick to a real-world, ‘one instrument, one note’ model, thereby maintaining a close relationship between MIDI arrangement and score. But when your sampled orchestration is intended as the final version, I’d advocate a more flexible attitude: if you like the lush sound of three unison flutes playing chords, keep it in there and don’t worry about the theory. As mentioned before, while it’s good to keep authenticity in mind, when working with samples it’s arguably better to go for engagement and expression, rather than focusing too narrowly on realism.

Woodwind Melody

A simple and highly effective use of woodwinds is the quiet, exposed melody line played by a solo instrument. An almost clichéd example is the cor anglais solo from Movement II of Dvorak’s Symphony No. 9 (popularly known as the New World Symphony), a sweet, pentatonic, folksy tune which tugs at the heartstrings. Tchaikovsky’s Suite From Swan Lake opens with a plaintive oboe solo, and Vaughan Williams’ Oboe Concerto in A minor also features beautiful solo oboe lines with strings accompaniment.

Such expressive oboe passages have become indelibly associated with idyllic rural scenes and pastoral imagery, perhaps because the simple, almost primitive sound of a solo reed instrument stirs up genetic memories of a pre-industrial, unspoiled natural world... or maybe it’s because film composers always dial up an oboe for romantic countryside scenes. Whatever the reason, if an agency asks you to supply music for any TV ad involving butter, cows, milk, cream, wheat, bread, honey, farms or rustic landscapes, be sure to include a poignant solo oboe line and they’ll think you’re a genius.

Elsewhere in the classical literature, Debussy’s Prelude to the Afternoon Of A Faun opens with a languorous, steamy solo flute line evocative of the god Pan taking a leisurely sauna in the Garden of Eden. The opening movement of Jacques Ibert’s Flute Concerto, featuring nippy staccato 16th-note ostinatos and a lyrical romantic melody within the first 60 seconds, also gives a good idea of what the instrument is capable of. Moving on to the clarinet, Pines Of Rome by the Italian composer Ottorino Respighi contains a lovely solo played over very nice string chords in the third movement (‘The Pines of the Janiculum’), roughly 10 minutes and 15 seconds after the start of the piece. A better-known clarinet moment is the outrageous glissando slide at the front of Gershwin’s Rhapsody In Blue, a fabulous piece which combines classical elements with jazzy effects — an early example of classical fusion, you might say.

It would be a brave media composer who would start a trailer soundtrack with a quiet bassoon solo, particularly if the brief demanded an ‘action-packed, epic, massive, booming, high-adrenaline score’ of the sort described earlier. These constraints were evidently not on Stravinsky’s mind when he penned what has arguably become the most iconic bassoon passage in musical history: it occurs in The Rite Of Spring, which memorably opens with a solo bassoon played in a very high register. Again, a reed instrument is used in celebration of the natural, pagan world, but this example didn’t catch on in the same way as the lonely-shepherd-on-a-hill oboe solo (possibly because the piece caused a near-riot at its premiere).

Dynamic Contrast

An absolutely classic orchestral device is to follow a loud section featuring all the instruments (aka tutti) with a quiet, reflective passage performed by a solo oboe, cor anglais or flute. After a triumphal, storming fortissimo rendition of your heroic main theme banged out by braying brass, searing strings, thundering taiko drums and the massed ranks of the Dagenham Girl Pipers, you can suddenly drop the dynamic down, silence the loud instruments and introduce a poignant woodwind tune over a light accompaniment. This tried-and-tested ‘orchestral breakdown’ trick is as old as the hills, but it works every time.

A good example can be heard in film composer maestro John Williams’ Adventures On Earth from the movie E.T. (The Extra-Terrestrial) at around 3m 40s. After a big brass build-up, a loud, climactic final accent gives way to a quiet sustained violins major chord, over which the cor anglais plays a short, reflective, mystical-sounding melody in the Lydian scale (a favourite mode of this composer). A similar event occurs around 8m 30s-8m 40s, but this time the piccolo plays the mystic tune over a bed of shimmering harp arpeggios and tremolo violin chords. It’s tremendously effective, and an object lesson in orchestral dynamic and tonal contrast.

Diagram 6: Lyrical oboe line from a film cue penned by the author.(Check out Jay Bacal’s masterly mock-up of Adventures On Earth, listed under ‘Masterpieces’ at Vienna Symphonic Library’s Music page www.vsl.co.at/en/Music/MusicPlaylists.)

Diagram 6: Lyrical oboe line from a film cue penned by the author.(Check out Jay Bacal’s masterly mock-up of Adventures On Earth, listed under ‘Masterpieces’ at Vienna Symphonic Library’s Music page www.vsl.co.at/en/Music/MusicPlaylists.)

For my humble part, I used the same device in a film music cue a few years back. By no stretch of the imagination can I be considered a major-league composer (I’m more in the Evo-Stik Division One South West league bracket, currently locked in a bitter relegation struggle), but keen-eyed musicologists will observe that the oboe tune I wrote starts with an open fifth interval, which seems to be one of the hallmarks of this style. You can see it notated in Diagram 6.

![Diagram 7: Extract from film composer Mike Verta’s The Race featuring alternating oboes (top stave) and clarinets. [Score extract used by kind permission of Mike Verta. Copyright 2011 Tudor-Ford Music, BMI.] Diagram 7: Extract from film composer Mike Verta’s The Race featuring alternating oboes (top stave) and clarinets. [Score extract used by kind permission of Mike Verta. Copyright 2011 Tudor-Ford Music, BMI.]](https://dt7v1i9vyp3mf.cloudfront.net/styles/news_preview/s3/imagelibrary/t/tso_pt4_07-vCsprteraTrrIlCv0yyO8MeOtIQr6A6b.jpg) Diagram 7: Extract from film composer Mike Verta’s The Race featuring alternating oboes (top stave) and clarinets. [Score extract used by kind permission of Mike Verta. Copyright 2011 Tudor-Ford Music, BMI.]Riffling through the popular classics, I noticed that poignant melodies of this sort are often alternated between oboe (or cor anglais) and flute, exploiting the two instruments’ dramatic contrast in tone. Well-known examples include Grieg’s ‘Morning Mood’ from Peer Gynt and Rossini’s William Tell Overture (the quiet Andante movement, around 6m 14s — not the galumphing, galloping bit at the end). Diagram 7 shows how composer Mike Verta does it in his excellent piece The Race: Suite For Orchestra, which I introduced last month. The melody alternates between two oboes and two clarinets — the oboes play the initial melody, sustain a note underneath the clarinets’ contribution, then play the final phrase. The last bar (in which the oboes perform a diminuendo on the note of C) coincides with the beginning of the strings passage in F featured in my previous article.

Diagram 7: Extract from film composer Mike Verta’s The Race featuring alternating oboes (top stave) and clarinets. [Score extract used by kind permission of Mike Verta. Copyright 2011 Tudor-Ford Music, BMI.]Riffling through the popular classics, I noticed that poignant melodies of this sort are often alternated between oboe (or cor anglais) and flute, exploiting the two instruments’ dramatic contrast in tone. Well-known examples include Grieg’s ‘Morning Mood’ from Peer Gynt and Rossini’s William Tell Overture (the quiet Andante movement, around 6m 14s — not the galumphing, galloping bit at the end). Diagram 7 shows how composer Mike Verta does it in his excellent piece The Race: Suite For Orchestra, which I introduced last month. The melody alternates between two oboes and two clarinets — the oboes play the initial melody, sustain a note underneath the clarinets’ contribution, then play the final phrase. The last bar (in which the oboes perform a diminuendo on the note of C) coincides with the beginning of the strings passage in F featured in my previous article.

(A video of The Race recording session can be seen at www.youtube.com/watch?v=xI1kdVtWKcU. The piece is also dissected at great length in Mike’s ‘Putting It All Together’ online masterclass, available from his web site www.mikeverta.com.)

Woodwind Harmony

Diagram 8: Simple chord triads work very well in woodwind writing.When it comes to harmonising woodwinds, a simple way of strengthening melody lines is to double them in the higher octave (the same technique discussed in last month’s string-writing article). Here your friend is the piccolo, a hard-working instrument which will happily double your flute or clarinet melody up the octave, often to near-deafening effect. I always enjoy hearing this in action in the intro of the Miracles’ Tamla classic ‘(Come ‘Round Here) I’m The One You Need’, a masterpiece of orchestral pop arranging which also features some great string parts.

Diagram 8: Simple chord triads work very well in woodwind writing.When it comes to harmonising woodwinds, a simple way of strengthening melody lines is to double them in the higher octave (the same technique discussed in last month’s string-writing article). Here your friend is the piccolo, a hard-working instrument which will happily double your flute or clarinet melody up the octave, often to near-deafening effect. I always enjoy hearing this in action in the intro of the Miracles’ Tamla classic ‘(Come ‘Round Here) I’m The One You Need’, a masterpiece of orchestral pop arranging which also features some great string parts.

Simple triads work well on woodwinds. Diagram 8 shows four three-note chords moving over a pedal bass note of G: using the same MIDI sequence, I orchestrated this for flutes (from the top down, two flutes, alto flute and bass flute) clarinets (three Bb clarinets and a bass clarinet) and bassoons (three bassoons and a contrabassoon). All three combinations sounded great, but predictably, the chords worked less well with the oboe family (two oboes, cor anglais and a bass oboe), which sounded somewhat shrill until I reduced the dynamic from fairly loud to quiet.

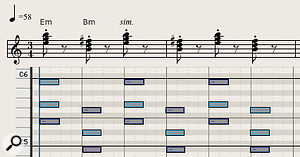

Diagram 9: Spooky staccato flute chords from a sci-fi chiller.Staccato flute chords are another appealing woodwind timbre, and worked supremely well in a tense, dreamy ‘clock-ticking’ cue in a famous sci-fi film (see Diagram 9), played over a sustained violins note of B played in octaves. If you can’t read music, try to work out the pitches from the piano roll notes (Tip: the same pair of chords repeats twice.)

Diagram 9: Spooky staccato flute chords from a sci-fi chiller.Staccato flute chords are another appealing woodwind timbre, and worked supremely well in a tense, dreamy ‘clock-ticking’ cue in a famous sci-fi film (see Diagram 9), played over a sustained violins note of B played in octaves. If you can’t read music, try to work out the pitches from the piano roll notes (Tip: the same pair of chords repeats twice.)

Diagram 10: Woodwind quartet parts for another of the author’s compositions. From the top down, oboe, clarinet, French horn (often used as part of a woodwind line-up) and bassoon.I’ll leave you with an extract from a piece I wrote many years ago (Diagram 10). Originally written on keyboard, I later added woodwinds and was pleased with the results. Interestingly, the line-up I used at the time was (from the top down) oboe, clarinet, French horn and bassoon. It’s quite common for a horn to appear in a woodwind line-up, but had a horn player not been available, a second clarinet would have done the trick.

Diagram 10: Woodwind quartet parts for another of the author’s compositions. From the top down, oboe, clarinet, French horn (often used as part of a woodwind line-up) and bassoon.I’ll leave you with an extract from a piece I wrote many years ago (Diagram 10). Originally written on keyboard, I later added woodwinds and was pleased with the results. Interestingly, the line-up I used at the time was (from the top down) oboe, clarinet, French horn and bassoon. It’s quite common for a horn to appear in a woodwind line-up, but had a horn player not been available, a second clarinet would have done the trick.

Coda

While the trend towards woodwind-free tracks continues unabated in trailer-music world, a spirited resistance is being fought in some quarters. Next month we’ll look at more examples of how creative film and TV composers use woodwinds in their tracks, including rhythm parts, runs and the subtle art of symphonic infill. I’ll also discuss the issues of mixing woodwind parts in a full-orchestra arrangement. In the meantime, I hope you enjoy listening to some of the musical selections listed above!

The Sampled Orchestra: Part 1 Getting Started

The Sampled Orchestra: Part 2 Basic String Writing

The Sampled Orchestra: Part 3 Essential String Playing Styles

The Sampled Orchestra: Part 4 Basic Woodwind Writing

The Sampled Orchestra: Part 5 Into The Woods

The Sampled Orchestra: Part 6 The Brass Family

Masterclass Tip: Extreme Keyswitching

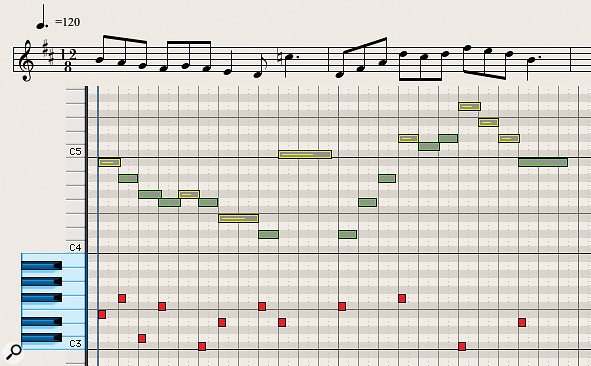

As mentioned in previous articles, many sound companies provide ‘keyswitch’ patches which group together commonly used playing styles (aka ‘articulations’) under one roof. Although some composers find it simpler to use a separate instrument track for each articulation, I’ve found keyswitching to be essential for increasing the realism and expression of an exposed woodwind solo line, particularly when the melody has a lively rhythmic character.

Diagram 11: Keyswitching is taken to extremes in this lively flute melody. Thankfully, most woodwind melody lines work well with only one or two articulations!

Diagram 11: Keyswitching is taken to extremes in this lively flute melody. Thankfully, most woodwind melody lines work well with only one or two articulations!

Here’s an example: Diagram 11 shows six different articulations at work in a lively, folksy flute melody, using VSL’s Vienna Instruments Player’s custom keyswitch facilities. The keyswitches (silent notes used for switching purposes only, marked in red) follow this scheme: C3 = legato, C#3 = legato marcato, D3 = sustain vibrato (not used in this example), D#3 = portato long vibrato, E3 = portato long no vibrato, F3 = portato short and F#3 = staccato. Note the logical progression of the keyswitches from long notes (legatos and sustains) to shorter portato (a medium-length, ‘carrying’ note) and staccato articulations — though it’s not obligatory, this scheme makes it easier to remember the keyswitch positions when programming.

As you can see, the tune is mainly short notes with a long dotted quarter note at the end of each bar and a passing quarter note halfway through the first bar. Apart from the obvious distinction between the short and long notes, the intention is not to vary note-length: many of the switches are there to exploit the different attacks of the various articulations, which produce helpful micro-variations of dynamic emphasis. Although all this seems terribly scientific (and admittedly takes a long time), it’s actually about optimising the melody’s rhythmic feel.

This is about as extreme as it gets — I’m not suggesting that using a different articulation for practically every note is desirable (in fact, it would drive you mad if you had to do it all the time), but in certain cases it’s an effective way of fine-tuning the rhythmic character of a phrase. If you fancy trying it, I suggest you record the phrase first using a single articulation that works for most notes, and add the keyswitches later. In order to keep track of what I’m doing, I tend to write the keyswitch notes by hand directly onto Logic Pro’s Piano Roll Editor (Key Editor in Cubase).

Woodwind Libraries

Below is a list of current orchestral woodwind sample libraries, which also includes modelled instruments by Sample Modeling and Wallander Instruments. The list is divided into two categories — woodwinds-only, and full orchestral collections which include woodwinds. As our focus is on core orchestral instruments, I’ve excluded ethnic and historic winds, but recorders (the historic predecessor of today’s orchestral flutes) are included. Specialised woodwind effects libraries will be covered later in this series, as will the saxophone family.

The figures in square brackets [ ] indicate each library’s number of mic positions excluding any mixes, while the GB figure shows its total size in gigabytes once installed. The latter number is not necessarily an indicator of musical muscle power: multiple mic positions automatically increase the number of samples without adding an iota of extra performance content, so a big GB count doesn’t necessarily indicate a large articulation menu.

WOODWINDS ONLY:

Vienna Symphonic Library www.vsl.co.at

- Woodwinds I [1] 41.6GB

- Woodwinds II [1] 44.9GB

- Special Woodwinds [1] 20.6GB

- Clarinet (Bb) 2 [1] 7.3GB

- Bassoon 2 [1] 3.7GB

- Recorders [1] 2.2GB

EastWest / Quantum Leap www.soundsonline.com

- Hollywood Orchestral Woodwinds [5] 133GB

Spitfire Audio www.spitfireaudio.com

- Spitfire Symphonic Woodwinds [3] 66.3GB

Orchestral Tools www.orchestraltools.com

- Berlin Woodwinds (Main library) [2] 53.2GB

- Berlin WW EXP A (Additional Instruments) [2] 7GB

- Berlin WW EXP B (Soloists I) [2] 7GB

- Berlin WW EXP C (Soloists II) [2] 5.6GB

Cinesamples www.cinesamples.com

- CineWinds Core [4] 18GB

- CineWinds Pro [4] 18GB

- Hollywoodwinds (phrases) [2] 3.7GB

Sonokinetic www.sonokinetic.net

- Woodwinds Ensembles [4] 50GB

Native Instruments www.native-instruments.com

- Symphony Series — Woodwind Ensemble [3] 57.9GB

- Symphony Series — Woodwind Solo [3] 33.4GB

Strezov Sampling www.strezov-sampling

- Flute Ensemble [4] unpublished

- Bassoon Ensemble [4] unpublished

Chris Hein www.chrishein.net

- Orchestral Winds Vol. 1 — Flutes [1] 6.7GB

- Orchestral Winds Vol. 2 — Clarinets [1] 6GB

- Orchestral Winds Vol. 3 — Oboes [1] 4GB

- Orchestral Winds Vol. 4 — Bassoons [1] 5.1GB

Embertone www.embertone.com

- Herring Clarinet [1] 1.6GB

- Recorders [1] 5.5GB

- Tenor Recorder [1] 0.61GB

8Dio www.8dio.com

- Piccolo Flute Virtuoso [3] 4.4GB

- Flute Virtuoso [3] 5GB

- Alto Flute Virtuoso [3] 6.6GB

- Oboe Flute Virtuoso [3] 4.5GB

- English Horn Virtuoso [3] 4.4GB

- Clarinet Virtuoso [3] 6.2GB

- Bassoon Virtuoso [3] 5.1GB

- 8Diooboe [3] 0.3GB

Samplemodeling www.samplemodeling.com

- The Flutes [1] unpublished

- Double Reeds [1] unpublished

- Clarinets [1] unpublished

Wallander Instruments www.wallanderinstruments.com

- Woodwinds & Saxophones [1] 0.35GB

MIXED ORCHESTRAL INSTRUMENTS:

Vienna Symphonic Library www.vsl.co.at

- Special Edition (six volumes) [1] 37.3GB

East West / Quantum Leap www.soundsonline.com

- EWQL Symphonic Orchestra [3] 194GB

Spitfire Audio www.spitfireaudio.com

- Albion One po [4] 50GB

- Albion III — Iceni po [5] 11GB

- Bernard Herrmann Composer Toolkit po [6] 146.6GB

Orchestral Tools www.orchestraltools.com

- Metropolis Ark 1 po [5] 70GB

- Metropolis Ark 2 (sections only) [5] 54GB

Sonokinetic www.sonokinetic.net

- Da Capo po [4] 7.9GB

8Dio www.8dio.com

- Majestica po [2] 23.7GB

Kirk Hunter www.kirkhunterstudios.com

- Diamond [1] 65GB

- Virtuoso Ensembles [1] 2.55GB

Project SAM www.projectsam.com

- Symphobia po [2] 17.4GB

- Symphobia 2 po [2] 18.2GB

- Orchestral Essentials 1 po [1] 16GB

- Orchestral Essentials 2 po [1] 10.6GB

Garritan www.garritan.com

- Garritan Personal Orchestra 5 [1] 11.6GB

- (The complete orchestral instrumentation of this budget collection is an excellent educational resource for beginners.)

NOTES:

po = pre-orchestrated. Instruments are blended into single patches; individual sections and instruments not provided.

Further Reading

If you find your appetite for woodwind wisdom whetted after reading this article, you might find it useful to look up some of the sources I referred to while preparing it:

Vienna Symphonic Library Academy:

www.vsl.co.at/en/Instrumentology/Woodwinds

Philharmonia Orchestra:

www.philharmonia.co.uk/explore/instruments

The Oxford Companion to Musical Instruments:

ISBN 9780193113343

Anatomy Of The Orchestra (Norman Del Mar, 1981):

ISBN 0-571-11552-7

Principles Of Orchestration (Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov, 1885):

http://northernsounds.com/forum/forumdisplay.php/77-Principles-of-Orchestration

Rockford Symphony Orchestra (General FAQs):

Oregon Symphony: