In this final part of the series, we show how well-chosen instrument combinations and effects will bring your orchestral arrangements to life.

As with cooking and football team selection, creating a successful orchestral arrangement is all about finding the right blend of ingredients. For the would-be chef, for example, mackerel, toffee, marzipan, liver and cherries might be delicious flavours in their own right, but you wouldn’t want to bake them all into a cake. Similarly, for the composer, an ill-chosen instrumentation combining Highland bagpipes, 12 contrabassoons and an ophicleide is unlikely to win many plaudits. To avoid horrible clashes and/or a muddy mess, skilful management of individual components is required.

Although the sampled orchestra offers exciting new sonorities, no serious arranger can afford to ignore the art of blending traditional orchestral timbres. As noted previously in this series of articles, learning to do this effectively no longer involves years of conservatoire study: today’s sample libraries deliver all the commonly used symphonic colours direct to your music room, while the ins and outs of DAW-based arranging are explained in detail in countless online walkthroughs (some, admittedly, more helpful than others). The combination of affordable virtual instruments and classic arranging techniques offers great opportunities — to reiterate my favourite Igor Stravinsky quote: “Now is the best time ever for music-making. It always has been.”

Tutti Frutti

Having investigated strings, woodwind and brass earlier in this series, we can now consider combining these families into a satisfying and engaging whole. The effect of all orchestral instruments playing together is known as tutti (the Italian word for ‘all’, as in tutti frutti, which means ‘all the fruits’). Speaking of fruit, as I sit writing this in the dying hours of 2017, my mind turns to an infamous London New Year’s Eve show I played with a friend’s band many years ago: the event was memorable mainly due to the audience pelting us with oranges mid-set, which I took to be a sign of their heartfelt appreciation. I remain grateful that the gig didn’t take place in Rome, as I wouldn’t fancy being bombarded with tutti frutti — those pineapples can give you a nasty headache.

No, not a photo of the author in his prog rock years — this is Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (1844-1908), composer and renowned orchestrator.Sorry, I digress. Whether arranging for a sampled or real orchestra, a particularly happy combination is strings and woodwinds. One standard technique is to soften a violin’s melody by adding unison clarinets or flutes, which, as one composer put it, “takes a bit of bite off the strings” — if the violins part is written in octaves, flutes can double the top line while oboes play the lower octave. Other effective string-woodwind pairings are listed in the ‘Combining Strings & Woodwinds’ box.

No, not a photo of the author in his prog rock years — this is Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (1844-1908), composer and renowned orchestrator.Sorry, I digress. Whether arranging for a sampled or real orchestra, a particularly happy combination is strings and woodwinds. One standard technique is to soften a violin’s melody by adding unison clarinets or flutes, which, as one composer put it, “takes a bit of bite off the strings” — if the violins part is written in octaves, flutes can double the top line while oboes play the lower octave. Other effective string-woodwind pairings are listed in the ‘Combining Strings & Woodwinds’ box.

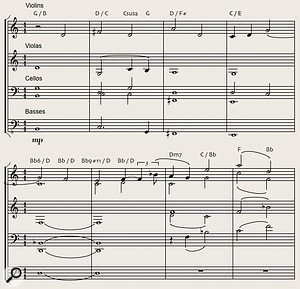

Owing to their dissimilarity of tone, combining strings and brass in a melody line is less straightforward, prompting the renowned orchestrator Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (1844-1908) to declare, “The combination of these two groups in unison can never yield such a perfect blend as that produced by strings and woodwind.” Nevertheless, adding horns to a violins melody line can produce great results, as demonstrated by the musical example shown in Diagram 1.

Diagram 1. Extract from ‘Song Of Titus’ by Sir Richard Rodney Bennett, as featured in the BBC TV series Gormenghast. Orchestration by John Wilson, score extract reproduced by kind permission of the composer.This diagram shows a short extract from Richard Rodney Bennett’s ‘Song Of Titus’, signature tune of the 2000 BBC TV adaptation of Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast. Its soaring theme is played by the classic combination of first violins doubled by second violins in the lower octave. To strengthen the melody and thicken the texture, the composer adds two French horns playing an octave below the second violins, producing a big, noble-sounding tune spanning three octaves. Accompaniment is provided by the lower strings (violas, cellos and double basses, not depicted) playing simple ostinato eighth-note figures which simultaneously keep the music moving while defining the underlying harmony, based on a beautifully lyrical chord sequence. To savour the full effect of this inspirational composition (previously featured in Part 6 of this series), I recommend you buy the Gormenghast soundtrack, which also includes choral music by John Tavener.

Diagram 1. Extract from ‘Song Of Titus’ by Sir Richard Rodney Bennett, as featured in the BBC TV series Gormenghast. Orchestration by John Wilson, score extract reproduced by kind permission of the composer.This diagram shows a short extract from Richard Rodney Bennett’s ‘Song Of Titus’, signature tune of the 2000 BBC TV adaptation of Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast. Its soaring theme is played by the classic combination of first violins doubled by second violins in the lower octave. To strengthen the melody and thicken the texture, the composer adds two French horns playing an octave below the second violins, producing a big, noble-sounding tune spanning three octaves. Accompaniment is provided by the lower strings (violas, cellos and double basses, not depicted) playing simple ostinato eighth-note figures which simultaneously keep the music moving while defining the underlying harmony, based on a beautifully lyrical chord sequence. To savour the full effect of this inspirational composition (previously featured in Part 6 of this series), I recommend you buy the Gormenghast soundtrack, which also includes choral music by John Tavener.

Mixing It Up

In his Principles of Orchestration treatise, Rimsky-Korsakov recommends the following strings and brass unison pairings: violin and trumpet, viola and horn, and cellos and horns (the last, often-used combination produces “a beautifully blended, soft quality of tone”). A low-end quadruple-whammy of cellos, double basses, trombones and tuba is also suggested for “massive heavy effects”. Such combinations succeed because of the closely corresponding ranges of the chosen instruments: by the same token, attempting to merge a piccolo trumpet with a double bass is doomed to failure, due to the instruments operating at opposite ends of the pitch spectrum. Rather than a smooth blend, we hear two distinct, wildly dissimilar timbres separated by a yawning four-octave gap.

While strings and woodwinds get along famously, mixing brass and woodwind can be problematical. Since the ‘heavy brass’ (trumpets, trombones and tubas) are so much louder than woodwind instruments, the best one can hope for when combining (say) a trumpet with a unison flute or clarinet is a subtle softening of the trumpet’s timbre. Even when two woodwinds are pitted against a trumpet, the latter usually comes out on top: this is clearly demonstrated in Spitfire Audio’s Bernard Herrmann Composer Toolkit sample library, which features, among other treats, a unison trio of trumpet, cor anglais and clarinet. While that sounds enticing, what you hear is a trumpet with a slightly unusual tone — unless you read the patch name, you’d never know the woodwinds were there.

The traditional solution to this David versus Goliath problem is to write woodwind parts in a higher octave, thereby placing them in a pitch zone brass can’t reach: one example would be to add flutes and oboes an octave above a trumpet. An alternative, distinctly untraditional solution would be to simply defy nature and turn the woodwinds up in the mix — this might incur the wrath of orchestral purists, but there’s no law against doing it. However, as well as ignoring the physical realities, adopting such an approach in a live performance would make life very difficult for the sound engineer! In practice, the disparity of volume is only an issue when woodwinds, trumpets and trombones are battling in the same register; substitute the heavy brass for horns (which enjoy a far more harmonious relationship with woodwinds by virtue of their quieter, softer tone), and the problem goes away.

As mentioned before in this series, one has to be cautious about sampled ensembles which were recorded playing in octaves. Back in the day when samples shipped on CD-ROM, I remember being disappointed that a very good brass collection’s ensemble samples were performed in two and even three octaves. The section sounded great on single notes, but turned into something resembling a pipe organ when you played a chord. Although pre-orchestrated octaves can be a time-saver when programming epic melodies, their lack of flexibility is a concern: if your MIDI arrangement is sounding too synthetic, over-use of parallel octaves may be the cause. In any case, the thick, intense sound of multi-octave doubling will become wearing if continued for too long — arrangers are advised not to make too much of a good thing, and reserve such full-range instrumental onslaughts for moments of high drama.

The symphony orchestra, dressed and ready for action.

The symphony orchestra, dressed and ready for action.

Filmic Atmospheres

When working with the full palette of orchestral colours, certain combinations of instruments and articulations are a surefire way of creating particular atmospheres and emotions. This is nicely demonstrated in film composer Mike Verta’s ‘The Race — Suite for Orchestra’, extracts from which were featured in Part 3 and Part 4 of this series. Written as an exercise in film-cue-style writing, this excellent composition runs through the entire gamut of familiar cinematic moods, three of which we’ll look at here. You can watch a video of ‘The Race’ recording session at www.youtube.com/watch?v=xI1kdVtWKcU.

Diagram 2. The minor-key ‘chase sequence’ theme from Mike Verta’s ‘The Race — Suite for Orchestra’. All extracts used by kind permission of the composer, copyright © 2011 Tudor-Ford Music, BMI.Diagram 2 depicts a classic, fast adventure-film ‘chase sequence’ minor-key theme, played over a full orchestral backing, which occurs one minute and 41 seconds into the piece. As shown in Diagram 3, the three trumpets start out in unison before breaking into two- and three-part harmony. Rhythmic momentum is provided by the cellos’ and basses’ staccato eighth-note ostinato patterns notated in Diagram 4, doubled by bassoon and bass clarinet respectively; the basses part is further reinforced by bass trombone and tuba, giving a great, pumping energy to the low end. The accents on the first and third beats are important, adding extra feel and drive to the rhythm. Trombones and violas play the same ostinato pattern in the middle register, with the two sections collectively harmonised into three-note chords which define the underlying chord progression (much of which takes place over a pedal note of C) shown in Diagram 3.

Diagram 2. The minor-key ‘chase sequence’ theme from Mike Verta’s ‘The Race — Suite for Orchestra’. All extracts used by kind permission of the composer, copyright © 2011 Tudor-Ford Music, BMI.Diagram 2 depicts a classic, fast adventure-film ‘chase sequence’ minor-key theme, played over a full orchestral backing, which occurs one minute and 41 seconds into the piece. As shown in Diagram 3, the three trumpets start out in unison before breaking into two- and three-part harmony. Rhythmic momentum is provided by the cellos’ and basses’ staccato eighth-note ostinato patterns notated in Diagram 4, doubled by bassoon and bass clarinet respectively; the basses part is further reinforced by bass trombone and tuba, giving a great, pumping energy to the low end. The accents on the first and third beats are important, adding extra feel and drive to the rhythm. Trombones and violas play the same ostinato pattern in the middle register, with the two sections collectively harmonised into three-note chords which define the underlying chord progression (much of which takes place over a pedal note of C) shown in Diagram 3.

Diagram 3. ‘Chase sequence’ theme from ‘The Race’ scored for three trumpets.

Diagram 3. ‘Chase sequence’ theme from ‘The Race’ scored for three trumpets. Diagram 4. Low strings driving, staccato eighth-note ostinato patterns propel the rhythm of the ‘chase sequence’ theme. Note the basses are written an octave higher than actual pitch.Although the mood is fairly serious, the final two bars of this passage introduce a touch of humour as the trumpets’ three descending minor triads are answered by a cheeky, cartoon-like woodwinds phrase (played in unison by two flutes, piccolo, two oboes and two clarinets). Note the quirky push-pull rhythmic effect in bar seven, where the three trumpet onbeat chords are echoed by accented offbeat cello pizzicato notes.

Diagram 4. Low strings driving, staccato eighth-note ostinato patterns propel the rhythm of the ‘chase sequence’ theme. Note the basses are written an octave higher than actual pitch.Although the mood is fairly serious, the final two bars of this passage introduce a touch of humour as the trumpets’ three descending minor triads are answered by a cheeky, cartoon-like woodwinds phrase (played in unison by two flutes, piccolo, two oboes and two clarinets). Note the quirky push-pull rhythmic effect in bar seven, where the three trumpet onbeat chords are echoed by accented offbeat cello pizzicato notes.

The second extract’s mood is a deliberate contrast to the first, being a heroic major-key theme designed to underscore this imaginary film’s ‘hopeful underdog’ character. Rather than a bombastic, Hans Zimmer-like ‘triumphant warrior’ approach, the composer opts for a simpler major-key progression, almost naïve in character but given a sweet lyricism by its soaring melody and moving (in both senses) chord sequence.

Diagram 5. A heroic major-key theme designed to underscore the ‘hopeful underdog’ character of ‘The Race’. The tune is shared between different instruments, a classic orchestral arranging device.The top lines are notated in Diagram 5: in time-honoured fashion, the tune is shared between different wind instruments — horns, solo trumpet, flutes and oboes in octaves and finally clarinets, each taking two bars in a melodic game of ‘pass the parcel’. This is classic orchestral arranging, taking advantage of the full orchestral line-up to contrast colours and create a mobile soundscape.

Diagram 5. A heroic major-key theme designed to underscore the ‘hopeful underdog’ character of ‘The Race’. The tune is shared between different instruments, a classic orchestral arranging device.The top lines are notated in Diagram 5: in time-honoured fashion, the tune is shared between different wind instruments — horns, solo trumpet, flutes and oboes in octaves and finally clarinets, each taking two bars in a melodic game of ‘pass the parcel’. This is classic orchestral arranging, taking advantage of the full orchestral line-up to contrast colours and create a mobile soundscape.

Diagram 6. String arrangement and chord sequence of the heroic major-key theme, featuring the recurring placement of the major third of the chord in the bass.Accompanying the ‘underdog hero’ theme is the lovely string arrangement you can see in Diagram 6. This is notable for its constant harmonic movement and recurring placement of the major third of the chord in the bass (as seen in the ‘slash chords’ in bars one, three, four, five and six), a harmonic device which always tugs at the heartstrings. This passage occurs at three minutes and 48 seconds in the YouTube video.

Diagram 6. String arrangement and chord sequence of the heroic major-key theme, featuring the recurring placement of the major third of the chord in the bass.Accompanying the ‘underdog hero’ theme is the lovely string arrangement you can see in Diagram 6. This is notable for its constant harmonic movement and recurring placement of the major third of the chord in the bass (as seen in the ‘slash chords’ in bars one, three, four, five and six), a harmonic device which always tugs at the heartstrings. This passage occurs at three minutes and 48 seconds in the YouTube video.

Victory At Last

The final extract from the ‘The Race’ sees our heroic underdog, having survived the dastardly machinations of a wily nemesis and his evil accomplices, emerging victorious (hey, this is Hollywood!), an outcome which demands suitably triumphal music. At this point, the composer reprises the melodic theme first heard 35 seconds into the piece; this time, the subdued romanticism of the initial theme statement gives way to a big, heroic and majestic treatment, with brass, horns and strings belting out the tune.

Diagram 7. String parts in three octaves play the ‘victory theme’ from ‘The Race’, a majestic tutti reprise of a melody first heard near the start of the piece.Diagram 7 depicts the string arrangement for this victorious passage: as you can see, violins, violas and cellos play the melody in three octaves, underpinned by the basses’ simple rhythmic pizzicato figures. The violins conclude with a dramatic descending flurry which has no melodic significance, but serves to add to the excitement. Two horns double the viola part; the three trumpets enter on the third bar, playing in unison with the high violins.

Diagram 7. String parts in three octaves play the ‘victory theme’ from ‘The Race’, a majestic tutti reprise of a melody first heard near the start of the piece.Diagram 7 depicts the string arrangement for this victorious passage: as you can see, violins, violas and cellos play the melody in three octaves, underpinned by the basses’ simple rhythmic pizzicato figures. The violins conclude with a dramatic descending flurry which has no melodic significance, but serves to add to the excitement. Two horns double the viola part; the three trumpets enter on the third bar, playing in unison with the high violins.

This extract’s chord sequence is shown in Diagram 8. Also notated is the supportive ostinato rhythm pattern played by the third and fourth horns as simple two-note chords, which helps flesh out the harmony while providing extra drive. The fast flute triplet figures are doubled by oboes, while the contrary-motion clarinets part is tracked in the lower octave by bassoons. Despite the blizzard of notes required to notate these woodwind parts, their effect on this music is subliminal: they create a kind of liquid, high-pitched swirl in which only the high part is faintly audible, but (as is often the case with woodwinds in tutti passages) you’d miss the clarinets and bassoons if they weren’t there.

Diagram 8. The chord sequence and decorative woodwind parts of the victory theme, underscored by rhythmic two-note horn chords.These climactic eight bars also feature harp triplets and light percussion touches (notably a glockenspiel adding its silvery, metallic ethereal chimes to the melody line). In keeping with classical orchestral arrangement, and as noted in Part 3 of this series, rhythmic momentum is provided by the pitched instruments playing rhythmic parts, leaving the percussion free to add decorative and dramatic interjections — no taiko drums in sight.

Diagram 8. The chord sequence and decorative woodwind parts of the victory theme, underscored by rhythmic two-note horn chords.These climactic eight bars also feature harp triplets and light percussion touches (notably a glockenspiel adding its silvery, metallic ethereal chimes to the melody line). In keeping with classical orchestral arrangement, and as noted in Part 3 of this series, rhythmic momentum is provided by the pitched instruments playing rhythmic parts, leaving the percussion free to add decorative and dramatic interjections — no taiko drums in sight.

‘The Race’ (which is deconstructed in Mike Verta’s ‘Putting It All Together’ online masterclass) strikes me as an ideal study for anyone interested in learning the art of orchestration and compositional development — for those wishing to explore further, the score can be purchased directly from the composer at http://mikeverta.com/pages/TheRace_Ordering.html.

Hit Parade

Diagram 9. The famous sforzato tutti ‘orchestra hit’ from Stravinsky’s The Firebird, used extensively as a sample on pop and hip-hop tracks. Note the tuba and basses are written an octave higher than actual pitch.Back in the early days of sampling, the Fairlight CMI helped revolutionise pop music. Despite its 8-bit sound quality, paltry RAM allocation of 16kB per voice and not-so-paltry £30,000 price tag, it was eagerly snapped up by wealthy 1980s pop stars who knew a good gimmick when they heard one. One Fairlight factory sound survives to the present day: the infamous ‘orchestra hit’ heard on tracks by Kate Bush, Afrika Bambaataa and Britney Spears, and embraced by the hip-hop community. The sample is taken from a recording of Stravinsky’s The Firebird, the opening note of ‘Infernal Dance Of All Kastchei’s Subjects’.

Diagram 9. The famous sforzato tutti ‘orchestra hit’ from Stravinsky’s The Firebird, used extensively as a sample on pop and hip-hop tracks. Note the tuba and basses are written an octave higher than actual pitch.Back in the early days of sampling, the Fairlight CMI helped revolutionise pop music. Despite its 8-bit sound quality, paltry RAM allocation of 16kB per voice and not-so-paltry £30,000 price tag, it was eagerly snapped up by wealthy 1980s pop stars who knew a good gimmick when they heard one. One Fairlight factory sound survives to the present day: the infamous ‘orchestra hit’ heard on tracks by Kate Bush, Afrika Bambaataa and Britney Spears, and embraced by the hip-hop community. The sample is taken from a recording of Stravinsky’s The Firebird, the opening note of ‘Infernal Dance Of All Kastchei’s Subjects’.

I’ve notated this iconic racket in Diagram 9 — it’s immediately identifiable from the high-pitched piccolo shriek at the top of the chord, a noise which will penetrate the densest, loudest orchestral performance. Similar big, accented hits can be heard in the classical repertoire down the ages, with some vigorous examples occurring in the first 11 seconds of the aforementioned ‘The Race’! Stravinsky’s effort is harmonically simple: all instruments play either an A or E note over an A bass note, making this the orchestral equivalent of a rock guitarist’s root-fifth-octave ‘power chord’.

Such tutti hits can also be played quietly, as in the opening chord stab of our man Rimsky-Korsakov’s ‘Flight Of The Bumblebee’ (from The Tale of Tsar Saltan), shown in condensed score form in Diagram 10. We know this piece from its insanely fast flute-and-violin tune, but it’s worth noting the accented E7 chord which kicks it off: the seemingly incongruous horn chord (incorrectly notated in modern scores) uses a top note of F, a hangover from the flattened-ninth harmony of the preceding music. Sorry to be pedantic, but this note made no sense until I heard what came before it!

Diagram 10. Less ear-splitting than the notorious ‘Firebird’ sample, this tutti hit is the opening chord stab heard underneath the hurtling tune of Rimsky-Korsakov’s ‘Flight Of The Bumblebee’.Tutti chords can be played as long notes, and their pitches, instrumentation and dynamic can be infinitely varied to taste. For example, change all the G#s and the horn F note in the ‘Bumblebee’ extract to G naturals, and you’d have a perfectly good Em7 chord! Classical composers traditionally ended their symphonies with a grand series of loud tutti chords, often ending with a crescendo on a final big, unequivocal, sustained unison note, recognised by all as a signal to rush for the exits.

Diagram 10. Less ear-splitting than the notorious ‘Firebird’ sample, this tutti hit is the opening chord stab heard underneath the hurtling tune of Rimsky-Korsakov’s ‘Flight Of The Bumblebee’.Tutti chords can be played as long notes, and their pitches, instrumentation and dynamic can be infinitely varied to taste. For example, change all the G#s and the horn F note in the ‘Bumblebee’ extract to G naturals, and you’d have a perfectly good Em7 chord! Classical composers traditionally ended their symphonies with a grand series of loud tutti chords, often ending with a crescendo on a final big, unequivocal, sustained unison note, recognised by all as a signal to rush for the exits.

You can hear the Firebird and ‘Flight Of The Bumblebee’ orchestra hits at https://soundcloud.com/bluerecording/firebird-orchestra-hit-sos/s-c6V7S and https://soundcloud.com/bluerecording/flight-of-bumblebee-orchestra-hit-sos/s-9CJEE. Thanks to Dr Pavol Brezina for creating these examples. Check out Pavol’s full rendition of ‘Flight Of The Bumblebee’ at http://youtu.be/GT_Mb7HJY2U.

Effective

Most orchestral libraries provide tremolo and trill articulations; many also include glissandos, grace notes and scale runs, while more specialised collections add exotica such as harmonic glissandi (for strings) and flutter tongue (brass and woodwinds). Such performances are a great way of adding colour and animation to a score — a good example occurs 17 seconds into ‘Flight Of The Bumblebee’, where the violin tremolos sound uncannily like the insect in question!

Stravinsky’s The Firebird is a rich resource of musical effects. Composed in 1909 as a ballet score, this piece has been a major influence on generations of composers due to its imaginative original musical ideas and highly colourful orchestration (significantly, Stravinsky was a student and friend of Rimsky-Korsakov). Take a dip into the score at www.youtube.com/watch?v=MHmk7yccvws and you’ll hear some fabulous effects: spooky harmonic glissandos at 1:42, the big ascending brass gliss at 28:30, accented hits with cymbals (29:30) and ensuing Tom & Jerry-style ‘uh-ohs’ (29:40), magical, swirling woodwind runs and harp glissandos (31:37) and xylophone-driven cartoon music at 32:23, not to mention the ‘Fairlight orchestra hit’ at 33:01.

In addition to these musical effects, some companies have taken to releasing collections of atonal, aleatoric and evolving-texture performances, featuring such items as cluster chords, rips, screeches, massed glissandos, pitch bends, random pizzicatos, wild improvs, etc. Taking the idea a step further, the contemporary trend for heavily processed material based on orchestral recordings is a sound designer’s dream, providing the basis for surreal and/or apocalyptic soundscapes which would be impossible to program with straight multisamples. The current crop of such sound libraries is listed in the ‘Orchestral Effects Sample Libraries’ box.

Coda

This month’s featured 19th Century Russian composer/orchestrator once said, “To orchestrate is to create, and this is something which cannot be taught.” Oh dear. However, he went on, “But invention, in all art, is closely allied to technique, and technique can be taught.” That makes sense; while not everyone has the confidence to try to write music, engaging with some of today’s associated techniques and processes can be a good starting point for a would-be composer. Working with orchestral samples is a big subject which may seem daunting at first, but do remember that we all have to start somewhere: the important thing is to use your brain and imagination, and don’t fall into the trap of thinking a software program can do it for you — if it does, it will probably come up with something pretty dull!

So there you have it. Thanks for sticking with me through this series, I hope you found it instructive. I enjoyed writing the articles (I learned some things myself, actually) and will now return to my lair, armed with sheaves of manuscript paper, a surfeit of samples, an overheated imagination and delusions of grandeur, to work on my next magnum opus.

The Sampled Orchestra: Part 1 Getting Started

The Sampled Orchestra: Part 2 Basic String Writing

The Sampled Orchestra: Part 3 Essential String Playing Styles

The Sampled Orchestra: Part 4 Basic Woodwind Writing

The Sampled Orchestra: Part 5 Into The Woods

The Sampled Orchestra: Part 6 The Brass Family

The Sampled Orchestra: Part 7 The Kitchen Strikes Back

The Sampled Orchestra: Part 8 Harp, Keyboards & Choir

The Sampled Orchestra: Part 9 Tutti & Effects

Orchestral Effects Sample Libraries

Below is a list of stand-alone orchestral ensemble effects libraries, focussing on played musical effects. The selection includes hybrid sound-design treatments based on orchestral material, but excludes phrase libraries and overtly electronic titles. (Note that although not strictly an effects library, Project SAM’s Symphobia is included, since its unusually large effects section comprises 50 percent of the library.)

As with previous lists in this series, the figures in square brackets indicate each library’s number of microphone positions excluding any mixes or processed versions, while the GB figure shows its total size in gigabytes once installed on your hard drive. Multiple mic positions automatically increase the sample count without adding extra performance content, so a large GB size doesn’t necessarily indicate a large articulation menu.

Spitfire Audio www.spitfireaudio.com

- Albion IV — Uist [4] 62.3GB

- Symphonic Strings Evolutions [4] 27.7GB

- Evo Grid 1 (Strings) [3] 27.6GB

- Evo Grid 2 (Strings) [3] 21.9GB

- Evo Grid 3 (Strings) [3] 21.3GB

- Evo Grid 4 (Woodwinds) [3] 17GB

- Olafur Arnalds Evolutions (Strings) [4] 15.2GB

- Orchestral Swarm [5] 29.7GB

Orchestral Tools www.orchestraltools.com

- Symphonic Sphere [3] 290GB

- Berlin Strings EXP E [4] 18.4GB

- Berlin Brass EXP C (French horn) [4] 4.9GB

- Berlin Woodwinds EXP D [4] 14.7GB

8Dio www.8dio.com

- CAGE Strings [9] 27.7GB

- CAGE Brass [9] 23GB

- CAGE Woodwinds [9] 14GB

- CASE Solo Strings [6] 22.2GB

- CASE Solo Brass [6] 4.4GB

- CASE Solo Woodwinds [6] 11.3GB

- Symphonic Shadows [2] 4.2GB

Native Instruments / Soundiron www.native-instruments.com

- Galaxy Instruments — Thrill [2] 31.6GB

Project SAM www.projectsam.com

- Symphobia [2] 17.4GB

- Symphobia Colours: Orchestrator [3] 4.9GB

Strezov Sampling www.strezov-sampling

- Aleatoric Modular Series: Trumpet [4] 4.3GB

- Aleatoric Modular Series: French Horns [4] 7.4GB

- Aleatoric Modular Series: Low Brass [4] 6GB

Heavyocity www.heavyocity.com

- Intimate Textures [3] 9.5GB

Gothic Instruments www.timespace.com

- Dronar Live Strings Module [1] 9GB

Zero-G www.zero-g.co.uk

- Animato [3] 4.6GB

Big Fish Audio www.bigfishaudio.com

- Tension: Orchestral FX & Elements [1] 2.9GB

Dynamic Sound Sampling www.dynamicsoundsampling.com

- Orchestral String FX [1] 1.4GB

Masterclass Tip: Taming The Robin

In order to avoid the so-called ‘machine-gun effect’ of the same sample being reiterated in a repeated-note passage, most sample libraries now provide alternative samples of the same note. These alternative samples automatically cycle through a predetermined sequence when a note is repeated, giving rise to the expression ‘round robin’. Often the alternative samples sound so similar that it’s hard to tell them apart, but their collective effect is more organic and convincing than hearing a mechanical repetition of a single sample.

Though round robins are generally hailed as good thing, one potential problem is that they can cause arrangements to never sound the same way twice. Here’s the problem: let’s say a note with two round-robin samples (RR1 and RR2) is repeated three times. On the first play, the note cycles through RR1, RR2 and RR1, but when you play the passage again, the cycle starts on RR2. In some cases (for example, when the RR2 sample has a slower attack than RR1, or if the two samples aren’t bang in tune), this can create subtle rhythmic or tuning disturbances. The more round robins there are in a patch, the greater the chance of audible discrepancies occurring on successive playbacks.

In order to give users full control over how their arrangements sound, some companies provide a ‘round robin reset’ function whereby pressing a button on the user interface resets the instrument’s round robin sequence to its start — this reset can be automated by assigning a MIDI note outside the playable range of the instrument to activate the button, then inserting that MIDI note at the top of your arrangement. It’s good practice to also insert the ‘RR reset’ note immediately before each main section in your piece, allowing you to start playback from any point safe in the knowledge that the incoming music will sound the same as it did previously!

Combining Strings & Woodwind

Here are some classic strings and woodwind combinations suggested by the master orchestrator Rimsky-Korsakov. Having written a melody using the unison pairings shown on the left, you can support it in the lower octave with the unison combinations listed on the right:

Upper part | Lower octave |

Violins & two clarinets | Violas, cellos & two bassoons |

Violas & two clarinets | Cellos, double basses & two bassoons |

Cellos & bass clarinet | Double basses & contrabassoon |

Cellos & bassoons | Double basses & contrabassoon |

When melodies are written in three octaves (as shown earlier in Diagram 1), Rimsky-Korsakov recommends these strings and woodwind combinations:

Top part | Middle octave | Low octave |

Violins & three flutes | Violas & two oboes | Cellos & two bassoons |

Violins I & piccolo | Violins II, flute & oboe | Violas, cellos, clarinets, cor anglais & bassoon |

Violins I & flute | Violins II & oboe | Cellos & cor anglais |

While these recommendations can be a useful starting point, they’re not carved in stone: rather than slavishly following a set of rules, you should experiment with your own instrumental combinations, and with a little luck and perseverance, you’ll hopefully discover some new permutations!