Creative woodwind writing is the orchestral arranger’s secret weapon.

Last month I introduced the woodwind instruments and gave examples of their usage in classical, film and contemporary media music. My focus was on an exposed melody line played by a solo instrument such as oboe or flute, but while that classic arranger’s standby always works a treat, it only scratches the surface of what woodwinds can do. In this article I’ll explore more areas of woodwind writing which, if handled with care, have the potential to transform a bread-and-butter arrangement into something far more magical and enticing.

Picture 1: The woodwind break in Smokey Robinson and the Miracles’ ‘The Tears Of A Clown’. From top: unison piccolo and harpsichord, oboe, bassoon. Dots on notes indicate staccato (a short detached note).In addition to being supremely good at melody, woodwinds are a great source of rhythmic propulsion. This is famously demonstrated by the woodwind-driven breaks in the much-covered Tamla Motown classic ‘The Tears Of A Clown’ by Smokey Robinson and the Miracles. I’ve notated the parts in Picture 1 — the top line is played by piccolo and harpsichord in unison, the middle line is handled by an oboe and the fabulous, jolly staccato bass line (which gives the breaks their rhythmic drive) is pumped out by a bassoon, played by orchestral musician Charles R Sirard.

Picture 1: The woodwind break in Smokey Robinson and the Miracles’ ‘The Tears Of A Clown’. From top: unison piccolo and harpsichord, oboe, bassoon. Dots on notes indicate staccato (a short detached note).In addition to being supremely good at melody, woodwinds are a great source of rhythmic propulsion. This is famously demonstrated by the woodwind-driven breaks in the much-covered Tamla Motown classic ‘The Tears Of A Clown’ by Smokey Robinson and the Miracles. I’ve notated the parts in Picture 1 — the top line is played by piccolo and harpsichord in unison, the middle line is handled by an oboe and the fabulous, jolly staccato bass line (which gives the breaks their rhythmic drive) is pumped out by a bassoon, played by orchestral musician Charles R Sirard.

On a side note, I always imagined this charismatic arrangement was written in response to the song’s subject matter, but in fact, it’s the other way round. According to Smokey Robinson, the backing track was written, arranged and recorded by fellow Motown artist Stevie Wonder (then aged 16), who brought it along to a Christmas party and asked the singer if he had any ideas for a song lyric. Inspired by the ‘circus-ey’ atmosphere of the woodwinds, Mr Robinson recalled the tragic character in the opera Pagliacci and proceeded to pen the immortal words: ‘Now there’s some sad things known to man, but ain’t too much sadder than the tears of a clown’. A sad thought indeed, but this colourful break is a positively joyful example of how woodwinds can energise a pop track.

Dumbarton Oaks

Thirty two years before ‘The Tears Of A Clown’ topped the singles charts, a new composition by the Russian composer Igor Stravinsky was receiving its first airing. Entitled Dumbarton Oaks, the piece (a concerto for chamber orchestra) was commissioned by a rich American couple, who had the privilege of hearing its first performance in the music room of their palatial mansion. Though occupying a different musical universe from the Motown record, Stravinsky’s work makes similar enjoyable use of staccato bassoon ostinatos, and also shares the distinction of being an all-time favourite of your humble scribe.

Picture 2: A short extract from Igor Stravinsky’s Dumbarton Oaks condensed to violins/strings top line with staccato bassoon accompaniment. Note that the bassoon’s up-and-down arpeggio is constructed entirely from fourth intervals!Picture 2 shows a short extract from Dumbarton Oaks that occurs approximately 1m 40s from the beginning of the piece. I’ve condensed the score to violins top line with bassoon accompaniment — I included the Am7add 4 strings chord in bars two and five to illustrate the harmony at those points, which is reinforced by the bassoon’s up-and-down, A-D-G-C-G-D phrase. You’ll notice that although the music is written in 2/4 time (two quarter notes per bar), the bassoon plays a repeated three-beat pattern. Stravinsky’s work is named after the posh Georgetown residence of its backers, a Mr and Mrs Bliss — if you ask me, a good alternative title (and one sure to please the sponsors) would have been The Bliss Variations, as that’s the effect this music has on me whenever I hear it.

Picture 2: A short extract from Igor Stravinsky’s Dumbarton Oaks condensed to violins/strings top line with staccato bassoon accompaniment. Note that the bassoon’s up-and-down arpeggio is constructed entirely from fourth intervals!Picture 2 shows a short extract from Dumbarton Oaks that occurs approximately 1m 40s from the beginning of the piece. I’ve condensed the score to violins top line with bassoon accompaniment — I included the Am7add 4 strings chord in bars two and five to illustrate the harmony at those points, which is reinforced by the bassoon’s up-and-down, A-D-G-C-G-D phrase. You’ll notice that although the music is written in 2/4 time (two quarter notes per bar), the bassoon plays a repeated three-beat pattern. Stravinsky’s work is named after the posh Georgetown residence of its backers, a Mr and Mrs Bliss — if you ask me, a good alternative title (and one sure to please the sponsors) would have been The Bliss Variations, as that’s the effect this music has on me whenever I hear it.

To render Stravinsky’s bubbling woodwind bass line with samples, use a solo bassoon staccato patch and notes will sound with the right short, tight delivery regardless of how you play them. Returning to ‘Tears Of A Clown’, the fast, fluid 16th-note bassoon arpeggio in the second bar would benefit from a legato articulation, and sustains are also needed for the oboe’s first four notes. In such cases, you can keyswitch between staccato and long-note samples on the fly — though a small detail in the overall score, articulation changes of this kind are a great aid to feel and musical realism.

Rhythmic Adventures

Picture 3: Typical high woodwind ostinato rhythm patterns, ranging from repeated single notes to a simple two-note melodic phrase.While the ostinato patterns outlined above sound great played by bassoons and bass clarinets, higher-pitched woodwinds can drive the rhythm just as effectively. Picture 3 shows some typical high woodwind ostinato rhythm patterns, ranging from repeated single notes to a simple two-note melodic phrase. These can be played by flutes, clarinets and oboes, or some combination of the three; the choice of instrumentation is entirely yours, and the beauty of using samples is that you can try different permutations without taxing the patience of live players! Moving such phrases up or down an octave (12 semitones) can produce good results, so don’t be afraid to experiment with different octave transposition settings in your MIDI track.

Picture 3: Typical high woodwind ostinato rhythm patterns, ranging from repeated single notes to a simple two-note melodic phrase.While the ostinato patterns outlined above sound great played by bassoons and bass clarinets, higher-pitched woodwinds can drive the rhythm just as effectively. Picture 3 shows some typical high woodwind ostinato rhythm patterns, ranging from repeated single notes to a simple two-note melodic phrase. These can be played by flutes, clarinets and oboes, or some combination of the three; the choice of instrumentation is entirely yours, and the beauty of using samples is that you can try different permutations without taxing the patience of live players! Moving such phrases up or down an octave (12 semitones) can produce good results, so don’t be afraid to experiment with different octave transposition settings in your MIDI track.

Rhythm figures of this sort can be enhanced by adding simple parallel harmonies, and if you want to push the boat out, you can spread your harmonies across multiple octaves. Picture 4 shows an example of this, as featured in the opening 3/4 bar of John Williams’ ‘Adventures On Earth’, a cue from the movie E.T. (The Extra-Terrestrial). Though the score looks complex, the music is based on a simple triadic chord movement.

Picture 4: High woodwind and string parts from John Williams’ ‘Adventures On Earth’. The piccolo part is shown in red, flutes in yellow, clarinets in blue and oboes in green, with mauve notes showing the additional D note played by the lower violas.In this extract, the two-note melodic phrase shown in Picture 3 is harmonised with lower parts of E-F#-E and C-D-C, creating a movement of C major to D major and back again. The parts are distributed across a wide pitch range, with a piccolo playing the top line high up in its top octave; two flutes play in thirds in the octave below, and the flute parts are doubled by a pair of clarinets an octave lower. Thus we have woodwind harmonies spanning three octaves, creating a colourful, ear-catching effect.

Picture 4: High woodwind and string parts from John Williams’ ‘Adventures On Earth’. The piccolo part is shown in red, flutes in yellow, clarinets in blue and oboes in green, with mauve notes showing the additional D note played by the lower violas.In this extract, the two-note melodic phrase shown in Picture 3 is harmonised with lower parts of E-F#-E and C-D-C, creating a movement of C major to D major and back again. The parts are distributed across a wide pitch range, with a piccolo playing the top line high up in its top octave; two flutes play in thirds in the octave below, and the flute parts are doubled by a pair of clarinets an octave lower. Thus we have woodwind harmonies spanning three octaves, creating a colourful, ear-catching effect.

Examining the parts, we can see that while the flutes and clarinets are close-harmonised, the two oboes are widely spaced; the higher oboe takes the C-D-C line while the other adds a new, independent D-C-D lower part, subtly enhancing the basic C to D major-chord harmony with (respectively) added 9th and 7th intervals. Played by a real orchestra, this combination of woodwinds and high strings produces a fabulous liquid, swirling sound — to reproduce that fluidity with samples, you’ll need to use a fast legato articulation and slightly overlap your notes. (As mentioned last month, Jay Bacal’s sampled mock-up and tutorial of this piece can be found at www.vsl.co.at/en/Music/MusicPlaylists.)

Picture 5: Double and triple-tongue performances can come in handy when programming repeated-note figures like the examples shown here.Moving on, when programming repeated-note figures like those shown in Picture 5, double and triple-tongue articulations (essentially two or three fast notes for the price of one) can come in handy. Vienna Symphonic Library woodwind ‘upbeat repetition performances’, available in double and triple-note repetitions, handle this job nicely. Orchestral Tools’ Berlin Woodwinds takes a different approach — when using its double and triple-tongue patches, you simply play a note, and the repeated notes sound when you release the key. Some libraries also provide multiple fast note repetitions played in a choice of breakneck tempos: with luck, these will sync nicely with your track straight out of the box, but if not, a little judicious time-stretching should make them fit.

Picture 5: Double and triple-tongue performances can come in handy when programming repeated-note figures like the examples shown here.Moving on, when programming repeated-note figures like those shown in Picture 5, double and triple-tongue articulations (essentially two or three fast notes for the price of one) can come in handy. Vienna Symphonic Library woodwind ‘upbeat repetition performances’, available in double and triple-note repetitions, handle this job nicely. Orchestral Tools’ Berlin Woodwinds takes a different approach — when using its double and triple-tongue patches, you simply play a note, and the repeated notes sound when you release the key. Some libraries also provide multiple fast note repetitions played in a choice of breakneck tempos: with luck, these will sync nicely with your track straight out of the box, but if not, a little judicious time-stretching should make them fit.

Runs & Trills

Another classic technique is a fast octave scale run up to an accented short target note, usually played by flutes and/or clarinets. This exciting, swirling effect is a great orchestral device which has been popular with composers for centuries. Picture 6 shows two typical examples — don’t be put off by the scary-looking septuplet marking, indicating seven notes played in the space of eight; in practice, only the timing of the first and last note is important — as long as those two events are on the beat, the intervening notes are not precisely clocked.

Picture 6: A fast octave scale run up to an accented short target note played by flutes and/or clarinets is a classic woodwind arrangement technique. Like stock-market shares, runs can go down as well as up!All the leading woodwind collections include ascending and descending octave runs in different scales and keys. Cinesamples’ Hollywoodwinds goes to town with this style, providing a comprehensive menu of beautifully orchestrated ensemble runs and simple rhythmic phrases, along with rips, straight notes and chords. Berlin Woodwinds’ Runs Builder feature provides a set of mini-phrases performed by flutes and clarinets, which you can sequence to create custom runs and ostinato patterns. Both libraries use Kontakt’s tempo-locking feature to keep the phrases in time with your arrangement.

Picture 6: A fast octave scale run up to an accented short target note played by flutes and/or clarinets is a classic woodwind arrangement technique. Like stock-market shares, runs can go down as well as up!All the leading woodwind collections include ascending and descending octave runs in different scales and keys. Cinesamples’ Hollywoodwinds goes to town with this style, providing a comprehensive menu of beautifully orchestrated ensemble runs and simple rhythmic phrases, along with rips, straight notes and chords. Berlin Woodwinds’ Runs Builder feature provides a set of mini-phrases performed by flutes and clarinets, which you can sequence to create custom runs and ostinato patterns. Both libraries use Kontakt’s tempo-locking feature to keep the phrases in time with your arrangement.

More instant woodwind action of this type can be obtained from VSL’s arpeggio samples — performed by solo flute and Bb clarinet, these four-note broken chords are supplied in all keys and a variety of scales, making them a useful resource for animated, cartoon-music-like figures.

Picture 7: Cinesamples Hollywoodwinds library provides a comprehensive menu of tempo-locked woodwind ensemble runs and simple rhythmic phrases.

Picture 7: Cinesamples Hollywoodwinds library provides a comprehensive menu of tempo-locked woodwind ensemble runs and simple rhythmic phrases.

As with note repetitions, you may have to experiment with the placement of these performances to achieve optimum sync with your track. Sometimes it’s easier (and more fun) to play the run or figure yourself, in which case you’ll need a fast-attack legato articulation, included with most orchestral libraries. Berlin Woodwinds’ Playable Runs patches are optimised for this task, offering fast legato transitions for all intervals up to a fifth. Such patches are usually monophonic and need a slight overlap between notes to trigger the real-life legato transitions.

Other engaging woodwind articulations include trills (a rapid alternation between two notes), usually supplied in semitone and tone flavours. The latter is a classic film score sonority, traditionally associated with seafaring scenes: in any movie made between 1935 and 1970, when a grizzled mariner whips out a telescope and yells, “Land ahoy, Mr Bosun!” from his vantage point at the top of a ship’s mast, expect a triumphant cymbal crash and a sudden outbreak of flute tone trills, usually harmonised in thirds. A less clichéd usage occurs in the opening of Stravinsky’s Petrushka, where combined clarinet tone trills of A and G, and D and E create a lovely shimmering effect under the jaunty, ‘Shrovetide Fair’ flute melody. You can hear the piece and read its score on YouTube at www.youtube.com/watch?v=3vGoToGx_7k.

In a similar vein, ornaments such as grace notes and mordents (a double grace note) will add instant animation to sampled arrangements, to the extent where a cynical media composer might be tempted to throw some into a score merely to impress a client with the wonderful realism of his or her sampled orchestra!

Symphonic Infill

Picture 8: Extract from ‘A Visit To Oz’, used by kind permission of its composer David William Hearn. Copyright DWH Music Ltd. From top down: unison piccolo and flutes, unison oboe and clarinet, cor anglais, two bassoons and contrabassoon.By combining the kind of woodwind rhythmic figures, runs and flourishes described above, enterprising orchestral sample users can add colour and movement to their scores. The music in Picture 8 is a good example: it’s an extract from ‘A Visit To Oz’ by composer, arranger and orchestrator David William Hearn, which you can hear at www.davidwilliamhearn.com/#music.

Picture 8: Extract from ‘A Visit To Oz’, used by kind permission of its composer David William Hearn. Copyright DWH Music Ltd. From top down: unison piccolo and flutes, unison oboe and clarinet, cor anglais, two bassoons and contrabassoon.By combining the kind of woodwind rhythmic figures, runs and flourishes described above, enterprising orchestral sample users can add colour and movement to their scores. The music in Picture 8 is a good example: it’s an extract from ‘A Visit To Oz’ by composer, arranger and orchestrator David William Hearn, which you can hear at www.davidwilliamhearn.com/#music.

The selected passage starts with a big brass stab 33 seconds in, and makes dramatic use of rhythmic accents (including a nice wrong-footed rhythmic shift in the third bar). I’ve shown the woodwind parts, which are scored for piccolo, two flutes, oboe, cor anglais, two clarinets (one doubling bass clarinet), two bassoons and contrabassoon. At this stage in the piece one clarinet doubles the oboe part while the other takes a breather, enabling me to condense all the woodwind parts onto four staves.

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, another busy musician is generating lively, creative and engaging scores that make great use of woodwinds. Picture 9 shows the opening bars of ‘Spirit Of Adventure’ by the award-winning film and TV composer Miles Hankins, whose credits include The Night Before, Len & Company, Fantastic Four, Hitman: Agent 47 and the animated Disney Channel series LEGO Elves. Check out the full version of ‘Spirit Of Adventure’ and other examples of Miles’ orchestral work at www.mileshankins.com.

Picture 9: Extract from ‘Spirit Of Adventure’, used by kind permission of its composer Miles Hankins. Copyright ASCAP.Though I’ve only shown the woodwind parts, there’s a lot going on in this short extract: the opening ascending ‘whoosh’ is doubled by violins and violas, after which three trumpets belt out a harmonised version of the staccato oboe rhythms. A heroic section of six French horns joins the fray in bar three, leaving us in no doubt we’re in classic Raiders Of The Lost Ark adventure-film territory: the bassoons’ bass line is powerfully reinforced by trombones, bass trombone, tuba and low strings, which adds considerable weight and grandeur. Meanwhile, flutes and clarinets intersperse their urgent, driving rhythmic figures with ascending octave runs, some of which are harmonised by the flutes playing an octave and a fifth above the clarinets.

Picture 9: Extract from ‘Spirit Of Adventure’, used by kind permission of its composer Miles Hankins. Copyright ASCAP.Though I’ve only shown the woodwind parts, there’s a lot going on in this short extract: the opening ascending ‘whoosh’ is doubled by violins and violas, after which three trumpets belt out a harmonised version of the staccato oboe rhythms. A heroic section of six French horns joins the fray in bar three, leaving us in no doubt we’re in classic Raiders Of The Lost Ark adventure-film territory: the bassoons’ bass line is powerfully reinforced by trombones, bass trombone, tuba and low strings, which adds considerable weight and grandeur. Meanwhile, flutes and clarinets intersperse their urgent, driving rhythmic figures with ascending octave runs, some of which are harmonised by the flutes playing an octave and a fifth above the clarinets.

‘Spirit Of Adventure’ has no ostinato percussion accompaniment, but that doesn’t weaken its effect: the rhythmic energy is entirely generated by woodwinds, strings and brass working together to propel the music. This is classic symphonic writing, combining and contrasting the different tone colours of the various instrument families to create a satisfyingly complex and evolving collective sound that never stands still.

Picture 10: Orchestral Tools’ Berlin Woodwinds offers a choice of no vibrato, normal vibrato and ‘progressive’ vibrato styles, which can be switched on the fly using MIDI CC commands.

Picture 10: Orchestral Tools’ Berlin Woodwinds offers a choice of no vibrato, normal vibrato and ‘progressive’ vibrato styles, which can be switched on the fly using MIDI CC commands.

Good Vibrations

Returning to the old standby of a poignant solo woodwind line played over a quiet backing, we should briefly consider the use of vibrato, that regular, rapid slight variation in pitch that singers and instrumentalists use to add expression to a sustained note. With the exception of clarinets, orchestral woodwinds are generally played with a controlled vibrato. Most orchestral sample libraries offer a choice of no-vibrato (NV) or vibrato samples, and some include the halfway house of ‘progressive vibrato’ — nothing to do with the ’70s musical style, these are performances in which the player gradually introduces vibrato to a sustained note.

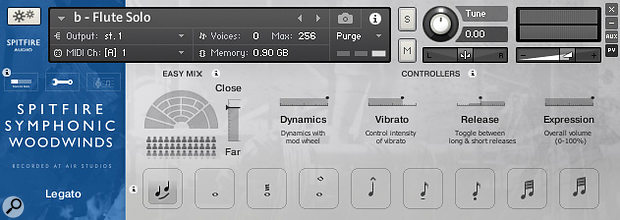

When programming sensitive melody lines, the point at which vibrato is introduced in a note can be critical. Spitfire Audio’s Symphonic Woodwinds gives users control over this timing: an on-screen fader enables you to add vibrato whenever you need it, and a MIDI controller can be assigned to the fader so you can sequence your vibrato moves. What you hear is not the horrid, synthetic pitch wobble used on keyboard workstations and early orchestral sample libraries — this is the real thing, a natural fluctuation of air pressure produced by breath control, enabling us to enjoy the organic and expressive vibrato style of a real player.

Spitfire Audio’s vibrato fader works by cross-fading no-vibrato and with-vibrato samples. If you’re feeling adventurous, you can create your own vibrato cross-fade instruments by following the instructions in the ‘Masterclass Tip’ box.

Picture 12: Spitfire Audio’s Symphonic Woodwinds’ on-screen fader enables you to add vibrato to a held note whenever you need it. A MIDI controller can be assigned to the fader so you can sequence your vibrato control changes.

Picture 12: Spitfire Audio’s Symphonic Woodwinds’ on-screen fader enables you to add vibrato to a held note whenever you need it. A MIDI controller can be assigned to the fader so you can sequence your vibrato control changes.

Mixing Woodwinds

A few words on mixing: woodwind textures can be extremely subtle, so adding them to your arrangement requires sensitivity. In a pop mix, it can be argued that every instrument needs to be heard distinctly, but orchestral sound doesn’t work like that — instruments meld together into ever-shifting, composite timbres, and achieving a good blend sometimes means you won’t be able to pick out a particular instrument or section.

Composer/orchestrator Robin Hoffmann had these thoughts on the subject, published in the ‘Daily Film Scoring Bits’ section of his web site www.robin-hoffmann.com on June 12th 2012: “It is in the nature of orchestral music to not be able to hear every instrument clearly in the mix. Some instruments like woodwinds even regularly ‘drown’ in tuttis [full orchestra passages] and their only purpose is to add to the ensemble sound. This is actually a main factor of creating that ensemble sound.”

Mike Verta (whose piece ‘The Race’ was featured in previous articles) has some interesting observations on the topic: in his Masterclass video tutorial Putting It All Together, the composer explains how doubling a strings melody with a clarinet has a softening effect — as he puts it, “It takes a bit of bite off the strings.” Another trick is three clarinets playing fast, quiet 16th notes in the accompaniment to the oboes and flutes melody featured last month (when I mistakenly said this melody is played by oboes and clarinets. Sorry about that!) — the effect is subliminal in both cases, but you’d miss the clarinets if they weren’t there.

The point here is that woodwinds can add texture and musical detail without grabbing your attention, or even without being clearly audible. This makes sense when you consider the real-world relative volume levels and section sizes of the instrument families: orchestral brass and percussion can be very loud indeed, and strings outnumber woodwinds by a factor of five to one, making woodwinds the quietest group (with one notable exception: the piccolo, which can make an amazing amount of racket for such a small instrument, and also grabs the ear by operating in a high pitch register that few other instruments can reach!).

The upshot of all this is if your woodwind parts are playing a supportive role, it’s OK to subtly merge them into the overall mix. On the other hand, if a solo woodwind is playing an important melody line, you can use pop-style volume automation on its track (as you would with a lead vocal) to ensure it’s not drowned out by the backing parts!

Coda

As has been copiously noted, debated, argued about and ruminated upon in Internet forums, there has been a move away from the traditional, woodwind-friendly orchestrations of classic film soundtracks to a simpler, more direct and in-your-face strings, brass and percussion instrumentation, as exemplified by scores from Hans Zimmer’s Remote Control Productions (RCP) stable. Some say this is purely thw result of commercial expediency — wannabe composers cashing in on an industry trend by adopting the RCP model — while others ascribe it to a lack of knowledge in writing for the instruments.

Either way, I feel that omitting woodwinds from a score is akin to cooking without condiments, but all is not lost: traditionalists should take comfort from the fact that Mr Zimmer’s score for Interstellar demanded six flutes, four oboes, six clarinets and four bassoons, with many of the players doubling on piccolos, alto flutes, cor anglais, Eb clarinet, bass clarinets, contrabass clarinets and contrabassoons — a veritable woodwind-fest. If any ghosts of the great composers are reading this, don’t despair — we’re sorry you’ve moved on to the great concert hall in the sky, but down here on the crust, woodwinds are alive and kicking.

With that happy thought, I’ll take my leave. Please feel free to cast your eyes over these pages next month, when I’ll introduce the orchestral brass family.

The Sampled Orchestra: Part 1 Getting Started

The Sampled Orchestra: Part 2 Basic String Writing

The Sampled Orchestra: Part 3 Essential String Playing Styles

The Sampled Orchestra: Part 4 Basic Woodwind Writing

The Sampled Orchestra: Part 5 Into The Woods

The Sampled Orchestra: Part 6 The Brass Family

Masterclass Tip: Vibrato Crossfading

Here’s a neat way of controlling the intensity and timing of a solo woodwind’s vibrato, courtesy of the aforementioned David William Hearn. (This first appeared in my article ‘Arranging For Strings (Part 3)’ in SOS August 2012: http://sosm.ag/strings-pt3)

David explains: “I invariably use the mod wheel (MIDI CC#1) as a dynamic controller, which means that in my orchestral templates, MIDI CC#11 (traditionally used as the Expression controller) is freed up for other functions. I’ve found it’s very effective to use an expression pedal to crossfade between non-vibrato and vibrato versions of instruments: it works well on solo woodwinds such as flute, and also string ensembles.

Here’s how to set up a vibrato crossfade using the Vienna Instrument and ‘Flute 1’ from Vienna Symphonic Library’s Woodwinds I collection: load the patch ‘FL1 sus Vib’ into one Vienna Instrument and ‘FL1 sus noVib’ into a second Vienna Instrument. Set both instruments to the same MIDI channel. Click on the second VI’s ‘Perform’ tab, select ‘Map Control’, highlight ‘CC11 Expression’ at the top of the controller list and click on the ‘Invert’ button, as shown in diagram 11.

Picture 11: You can create your own vibrato crossfades by mapping a MIDI control change to positive and negative volume curves — in this example, CC#11 (Expression) is used to crossfade between non-vibrato and vibrato versions of the same instrument.

Picture 11: You can create your own vibrato crossfades by mapping a MIDI control change to positive and negative volume curves — in this example, CC#11 (Expression) is used to crossfade between non-vibrato and vibrato versions of the same instrument.

Inverting the second instrument’s Expression curve has the effect of making the non-vibrato flute get quieter when you press down your expression pedal, while the vibrato flute simultaneously gets louder. Pull back the pedal, and the reverse happens. This means you can start off a note without vibrato and introduce it at will via the pedal; a nice, expressive technique and a big improvement on using ‘progressive vibrato’ instruments in which the vibrato always kicks in at the same point. And of course, while varying the vibrato intensity, you can also add volume swells and fades with the mod wheel”

What’s In A Name?

Although not all orchestral woodwinds are actually made of wood, they were when the term first came into general use. The first all-metal flutes appeared in the mid-19th century, leading to today’s expensive, professional-quality instruments made of sterling silver (budget flutes are usually constructed of silver-plated, polished brass). Woodwinds are now made of a variety of materials: the modern clarinet has a hardwood body, a mouthpiece made of hard rubber, plastic, glass or crystal (sometimes metal), silver keys, and cork tenons to connect its five parts — a miracle of multi-material engineering.

Nevertheless, ‘woodwinds’ has a nice ring to it. The word clearly touched the hearts of a pair of young Dutch music fans I met who, having read it in an album credits, asked me to confirm that it referred to the evocative, mournful sound of the wind blowing through the woods (a fair assumption, given that the player in question, Jimmy Hastings, has an exceptionally lyrical flute style). When I explained it simply meant a wooden wind instrument, the guys were visibly disappointed. On reflection, I should have gone along with their poetic interpretation, which charmingly conveys the subtle emotions stirred up by beautifully played solo woodwinds.