You don’t have to play synths or ‘real’ instruments to make music: embrace the experimental, and you could use almost anything...

I’ve produced tracks in many different genres over the years, but when making my own music one of my favourite styles is what I call ‘ambient’. Being honest, I don’t know if that’s the perfect description for what I make — ‘ambient’ can mean different things to different people. But online distribution forces me to put my music into a category, and while there are elements of chillout and electronica in my music, it doesn’t fit those genres neatly, and neither does it feature the sort of rhythms you’d find in trance or EDM. And who wants to get bundled in with New Age?!

Whatever we call it, it’s a style that features lots of sound-design elements, some based on musical sources, others more from found sounds, such as mechanical noises and spoken word. I aim to conjure up a chilled overall feel, and this often turns out to be a fine balancing act, as there must be enough happening to hold the listener’s attention, but not so much as to break the mood of the piece.

The style inspires me to explore my DAW’s editing tools and my sound-mangling plug-ins and gadgets in a way that more structured forms typically don’t, and as this sound-design approach could be used to benefit other genres — and because the reception my demonstration to a packed audience at last year’s New York AES suggests the style might be more popular than I’d initially thought — I decided to explain my approach here.

The style inspires me to explore my DAW’s editing tools and my sound-mangling plug-ins and gadgets in a way that more structured forms typically don’t, and as this sound-design approach could be used to benefit other genres — and because the reception my demonstration to a packed audience at last year’s New York AES suggests the style might be more popular than I’d initially thought — I decided to explain my approach here.

To accompany the article, I’ve provided a set of audio files (see sidebar at the right) taken from my AES seminar. These include before and after examples of the techniques I discuss here, as well as a mix of a short tune created specifically to showcase the processes I discuss. For more examples, check out the Bandcamp page of my current collaboration with musician Mark Soden, which goes under the name of the Cydonia Collective — all of the techniques covered here can be heard on both our debut album Stasis and our recently released follow-up Lost Horizon (https://cydoniacollective.bandcamp.com). So have a listen, and if the sounds and textures appeal to you, read on to discover how it’s done...

The Germ Of Inspiration

Brian Eno is famously keen on embracing the unintentional, and I totally understand where he’s coming from. Rather than first write a song and then lay it down, my compositions often start just with a simple melodic idea. Other parts spring from there, often as the result of experimentation — which leads to happy and not-so-happy accidents! The trick is to embrace the happy ones and simply ignore the rest, and then follow the more interesting and appealing new directions these parts suggest to you. Sifting through and editing improvised parts and early ideas often produces a section or two that serves as ‘seed material’ for the rest of the piece. The arrangements that I develop in this way could best be described as ‘evolutionary’ — they don’t follow a traditional verse/ chorus/ middle-eight structure.

Key elements in my music include long, evolving sounds that can be used in place of traditional synth pads or drones, ethereal piano treatments, ear-candy (patches of sonic ‘glitter’, used for punctuation), warm but non-intrusive bass sounds, processed natural or mechanical sounds, and realistic but smooth-sounding sampled strings. Electric and acoustic guitars also feature extensively, as I feel they add a pleasing ‘organic’ dimension to what could otherwise sound too obviously electronic. Not only do I tend to process these guitars differently from when working on pop or rock, but the actual playing style is often different too — my EBow sees a fair amount of service, for example. Really, though, you could start with pretty much any sounds you care to manipulate.

You Say Potato...

Most off-the-shelf synth pads, even the more complex evolving ones, rarely grab my interest beyond the first few seconds, so if I do use them I’ll tend to layer them with something else, such as an EBowed guitar or treated vocals, before applying further processing to the composite, layered sound. But it’s often much more inspiring to create pad sounds simply through the extreme processing of quite random audio recordings.

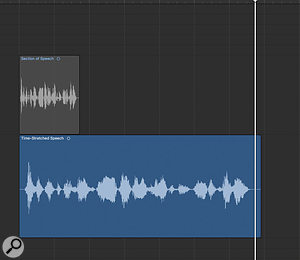

Pads from spoken word 1: I started with a simple spoken-word phrase. You can use anything, though note that the more pitch-modulation in the original recording, the better. Try to avoid (or edit out) sibilant sounds.

Pads from spoken word 1: I started with a simple spoken-word phrase. You can use anything, though note that the more pitch-modulation in the original recording, the better. Try to avoid (or edit out) sibilant sounds. Pads from spoken word 2: Use whatever time-stretching tools you have to stretch the clip to three or four times its original length. Don’t worry about processing artifacts; they’ll sound obvious at this stage, but we’ll address that later.For my AES seminar, I deconstructed a technique I often use to transform short sections of speech into musical pads. Since the final edited vocal doesn’t actually need to make any sort of lyrical sense, you can use pretty much anything as a starting point — in this case, I began with my former SOS colleague JG Harding reading out a definition of potatoes! My first action was to time-stretch his spoken phrase to around five or six times its original length, which obviously introduced noticeable processing artifacts while rendering the words almost unrecognisable. I then cut out the elements that were most adversely affected by the time-stretching (particularly breaths and sibilant sounds) before creating a reversed duplicate part on a new track, so the forward and the reversed sections could be played simultaneously. This resulted in a sort of dragged-out ‘alien grumble’.

Pads from spoken word 2: Use whatever time-stretching tools you have to stretch the clip to three or four times its original length. Don’t worry about processing artifacts; they’ll sound obvious at this stage, but we’ll address that later.For my AES seminar, I deconstructed a technique I often use to transform short sections of speech into musical pads. Since the final edited vocal doesn’t actually need to make any sort of lyrical sense, you can use pretty much anything as a starting point — in this case, I began with my former SOS colleague JG Harding reading out a definition of potatoes! My first action was to time-stretch his spoken phrase to around five or six times its original length, which obviously introduced noticeable processing artifacts while rendering the words almost unrecognisable. I then cut out the elements that were most adversely affected by the time-stretching (particularly breaths and sibilant sounds) before creating a reversed duplicate part on a new track, so the forward and the reversed sections could be played simultaneously. This resulted in a sort of dragged-out ‘alien grumble’.

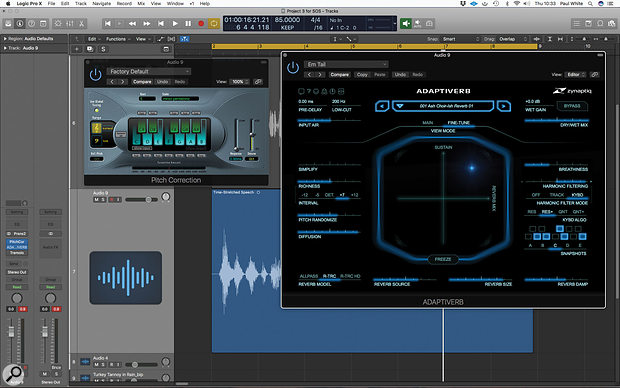

To turn this into something more musical, I inserted a real-time pitch-correction plug-in on each of the two ‘vocal’ tracks, and set them to their fastest pitch-correction speed. Importantly, you have to tune only to the notes of a scale or chord of your choice — in this case, a scale comprising just the three notes of the D minor chord. When the track is played back, you can hear the pitch ‘yodelling’ between the three notes as the original vocal pitch varied.

At this stage, listen carefully and address any issues. If any parts still sound particularly glitchy or unmusical, just chop them out with your DAW’s editing tools. If you need to lengthen a section, it usually works best if you first render the audio with pitch-correction — that way, you can crossfade it into a copy of itself without confusing the pitch corrector. Then it’s time to audition what you have, and separate out those parts that work really well from those which don’t. If you’re lucky, as the pitch-corrector does its thing, some material will start to suggest a basic melody around which to build your track.

Pads from spoken word 3: Insert a pitch-corrector, set to a scale of your choice and to its fastest correction. Then add delay and reverb to turn the vocal into something more musical. (Use little or none of the dry sound.)

Pads from spoken word 3: Insert a pitch-corrector, set to a scale of your choice and to its fastest correction. Then add delay and reverb to turn the vocal into something more musical. (Use little or none of the dry sound.)

All that’s needed for the next step is a generous helping of long reverb plus some simulated tape delay, which helps the pad sound assume a more organic, evolving quality. I also often remove a lot of low end from the reverb, typically with a 6 or 12 dB/octave low-cut filter at 300-400 Hz, to stop the sound getting too muddy. The delay is usually the same one I use for the guitar and piano parts (discussed below): a tape-delay emulation, sync’ed to the project tempo and with the lows rolled off at 600Hz and the highs at 1200Hz, to create a repeat that seems to fade into the distance. A bit of wow and flutter emulation, if you have a delay that offers that, can help the repeats degrade. (You’ll need to set the delay’s feedback after applying the filtering, as the EQ settings affect the output level, which in turn affects the number of audible repeats.) A further treatment that often sounds appealing is to put a rotary speaker plug-in, on its slow setting, at the end of the processing chain. This smooths out the sound further, as well as adding a welcome sense of movement.

If your reverb- and delay-drenched sounds still feel a little obvious, a slow rotary speaker plug-in can add smoothness and movement to just about anything! It makes a good alternative to chorus or phasing.A similar vocal approach that has yielded good results (but doesn’t feature in the AES example) requires you or a friend to sing nonsense phrases, ideally containing no breaths or sibilant S and T sounds, in as deep and throaty a growl as possible. Apply assertive pitch-correction and, as before, enable only the notes of the chord or scale you wish to use. Add delay and reverb, and the result can sound vaguely reminiscent of Tuvan throat singing, and generate unexpected melodies as the pitch-corrector flips between notes.

If your reverb- and delay-drenched sounds still feel a little obvious, a slow rotary speaker plug-in can add smoothness and movement to just about anything! It makes a good alternative to chorus or phasing.A similar vocal approach that has yielded good results (but doesn’t feature in the AES example) requires you or a friend to sing nonsense phrases, ideally containing no breaths or sibilant S and T sounds, in as deep and throaty a growl as possible. Apply assertive pitch-correction and, as before, enable only the notes of the chord or scale you wish to use. Add delay and reverb, and the result can sound vaguely reminiscent of Tuvan throat singing, and generate unexpected melodies as the pitch-corrector flips between notes.

Plug-in Power

So far, everything I’ve discussed is easily achievable using only your DAW and its bundled plug-ins and basic editing tools, but some third-party plug-ins can open the door to new processing tricks or more complex textures, or help you perform your existing tricks more efficiently.

Pads from spoken word 4: Zynaptiq’s Adaptiverb is particularly good at making your processed voice recording sound more musical, because you can set the reverb tail to ‘pick out’ specific scale notes.

Pads from spoken word 4: Zynaptiq’s Adaptiverb is particularly good at making your processed voice recording sound more musical, because you can set the reverb tail to ‘pick out’ specific scale notes.

I’m a big fan of Zynaptiq’s Adaptiverb, which allows you, via a pitch-correction-style keyboard, to select which note harmonics the reverb picks out. It can also throw pitch-shifting into the mix, or freeze the reverb spectrum from one sound and impose it on another. Adaptiverb’s reverb engine includes resynthesis, so the end result can sound somewhat like what you might expect from a spectral-processing instrument like iZotope’s Iris 2 (another powerful ally in this type of musical venture).

In my AES example, I used Adaptiverb to lend the processed vocal drone a shifting choir-like quality, and the resulting sound makes an appearance at a couple of points in the tune. For fashioning huge sounds that are outside the remit of conventional reverbs, I find that Eventide’s Blackhole offers an interesting alternative to conventional delay or reverb. Many of the more sophisticated reverbs and delays out there can be rather demanding of CPU power, so I tend to bounce the results down once I’ve arrived at suitable settings.

For more complex rhythmic effects, Output’s Movement plug-in (or, if you use Logic Pro, the bundled Step FX) can modulate multiple effects, with everything locked to your song tempo.

For more complex rhythmic effects, Output’s Movement plug-in (or, if you use Logic Pro, the bundled Step FX) can modulate multiple effects, with everything locked to your song tempo.

Another favourite tool is Output’s Movement, a powerful plug-in which can be used to add rhythmic interest to almost any source. It’s particularly useful for creating a pulsating feel (subtle or otherwise!), as it can modulate the parameters of several effects in different ways at the same time, and there are lots of tempo-sync options. I find that it works particularly well on bass lines, but I’ve also used it to chop a simple chordal guitar part into something rhythmic that sounds more like a tuned hi-hat than a guitar.

Much as I like this tool, though, it’s worth pointing out that you can achieve something similar with careful use of any tremolo plug-in that offers a choice of square or sine modulation waveforms and has a tempo-sync option — and you could also try side-chaining a gate from a rhythmic source, as long as the gate has a range/floor control.

Found Sounds

But it’s not all about plug-ins and melodies, as other sounds can add to the sense of atmosphere. Capturing random audio clips can provide an interesting starting point, and often provides plenty of inspiration. I’ll often record sections of speech when at an airport or railway station. These can be mixed in to add atmosphere — just insert them into a song at strategic points, such as over breakdown sections, at a fairly low, almost subliminal level. Sometimes, I’ll shift the pitch of the sample slightly, or use time-stretching to change the duration, but for the example mix, in which I used some speech recorded at a railway station, very little was done. Human breaths can also sound very atmospheric, as long as they’re not too loud. (If you’re disinclined to record such things yourself, try searching for inspiration online — the https://freesound.org website would be a good place to start.)

Tempo-sync’ed tremolos, or ‘choppers’, can inject a strong rhythmic feel into any of the sustained sounds used in an ambient production.A technique for further experimentation with such sounds is to use the aforementioned tempo-linked chopping tactic, using a square-wave-driven tremolo plug-in to modulate the voice. And if this idea appeals, why not go a step further? Set up two different voice samples playing at the same time and pan them opposite each other. Put a chopper on each and flip the polarity of one of the chopper plug-ins — the ‘slices’ of sound will alternate between the two tracks, creating an auto-panned tremolo effect which, on such material, can really add to the atmosphere.

Tempo-sync’ed tremolos, or ‘choppers’, can inject a strong rhythmic feel into any of the sustained sounds used in an ambient production.A technique for further experimentation with such sounds is to use the aforementioned tempo-linked chopping tactic, using a square-wave-driven tremolo plug-in to modulate the voice. And if this idea appeals, why not go a step further? Set up two different voice samples playing at the same time and pan them opposite each other. Put a chopper on each and flip the polarity of one of the chopper plug-ins — the ‘slices’ of sound will alternate between the two tracks, creating an auto-panned tremolo effect which, on such material, can really add to the atmosphere.

Mechanical Engineering

I mentioned earlier that I also use ‘natural’ mechanical sounds for rhythmic interest, and such sounds are all around us. Clocks, fridges, power tools, spray cans, wind chimes, rain-sticks, shells, toys and so on are all usable with just a little editing, time-stretching, occasional reversing and other processing to hide their true origins quite effectively. The deep tick you can hear on the example song is the recorded sound of a long-case clock in my house, which I cut up to lock it to the song’s tempo, and at the start of the track I used a winding sound from the same clock.

Again, happy accidents can frequently contribute something helpful: a creaking guitar bridge, a string squeak or just part of a single note stretched by a silly amount can end up sounding very interesting.

You’ll also sometimes find that short sounds can be combined to good effect, by crossfading segments of two or three different recordings. Near the start of the demo piece, you’ll hear a sound created by slowing and merging a wind chime and a wind gong. I find it great fun recording my own ear-candy effects in this way — but some companies also sell such sounds ready-made. For instance, Sub51 Sound Design (www.sub51.co.uk) produce a very low-cost library of one-shot ear-candy effects, including a few I donated.

It almost goes without saying that you can also create atmospheres using natural sounds such as water, wind, distant thunder, birds, jungle sounds, frogs, crickets, heartbeats and so forth. But you should probably try to avoid falling into the ‘crystals and lentils’ cliché trap! Ask yourself if these sounds can be used other than in their original form — for example, could they be integrated into some of your pad sounds, or might they contribute to the rhythm section?

Guitars & EBows

Parts played using the aforementioned EBow (an inexpensive monophonic ‘infinite sustain’ electronic bow for guitar) can be really useful for building up layers to create your own unique shifting pad sounds, or as a new layer to add textural movement to an existing pad. The unique thing about the EBow is that the harmonic content of the sound changes as you move it along the guitar strings. The sound is influenced by which pickups are active at the time, and the timbre also varies as you slide the bow between the pickup positions.

Things can become very interesting when you use an EBow to play a melody, and then use pitch-correction to constrain that melody to a single note, or a more restricted range of notes.To create chords, layer three or four EBow parts, each one playing a different note of the desired chord; the example song includes a musical fifth added to a basic drone. Feed the results to delay/reverb, as with the earlier techniques. Then adding a slow rotary speaker emulation afterwards makes a useful alternative to chorus or phasing. Things can also become very interesting when you use an EBow to play a melody, and then use pitch-correction to constrain that melody to a single note, or a more restricted range of notes. (You can hear this technique at play on some of the Cydonia Collective tracks.)

Things can become very interesting when you use an EBow to play a melody, and then use pitch-correction to constrain that melody to a single note, or a more restricted range of notes.To create chords, layer three or four EBow parts, each one playing a different note of the desired chord; the example song includes a musical fifth added to a basic drone. Feed the results to delay/reverb, as with the earlier techniques. Then adding a slow rotary speaker emulation afterwards makes a useful alternative to chorus or phasing. Things can also become very interesting when you use an EBow to play a melody, and then use pitch-correction to constrain that melody to a single note, or a more restricted range of notes. (You can hear this technique at play on some of the Cydonia Collective tracks.)

You don’t have to rely on the EBow, though; hard pitch-correction can also be effective on a lead guitar part (as in the example mix). If your guitar playing involves string bending and vibrato, the action of the fast pitch-correction produces a very Eastern feel, turning deep vibrato into trills, and speeding up any bends. Pitch-correction is also invaluable if you’re brave enough to play a harmonic and then use the vibrato arm to turn it into a melodic line — a trick that appears about halfway through the example mix. (While Jeff Beck might get this right 99.9 percent of the time, most of us mere mortals will, I’m sure, appreciate the electronic assistance!)

To create the doubling effect you can hear there, I simply layered the guitar part with an un-pitch-corrected copy of itself, delayed by around 30ms, and then added band-limited tape delay, as discussed earlier. Amp modelling was used to shape the basic guitar sound in this instance, but what you do is entirely down to your own artistic tastes.

Acoustic guitar (or clean electric guitar, DI’ed and with no amp emulation) can also sound very effective. Use compression to fill out the sound while enhancing sustain, add an appropriate delay and/or reverb, and it will fit right in. Your first instinct might be to use your ‘best’ reverb, but I like exploring low-horsepower plug-ins such as Logic Pro’s SilverVerb. Such reverbs often produce fairly low-density tails which sound too crunchy on drums but can sound lovely on guitar. Roll off some low end from the reverb to stop the overall sound becoming too muddy and, if the plug-in allows you to add gentle modulation, that can also make for a richer-sounding result. The trick is to add enough reverb (it really can be quite long) to create the right sense of space and distance but not so much that your mix descends into mud. Generous smatterings of such reverb can also flatter piano (invariably played with the sustain pedal down) and flute. If the low end starts to sound muddy, try increasing the reverb’s low-cut filter frequency and/or dropping the reverb level.

Another useful effect is the ‘shimmer-verb’, which is essentially a reverb that’s fed from an aux send that has its output shifted up in pitch by an octave. Used on acoustic or clean electric guitars it adds an almost string-like sheen. To set this up using your basic plug-ins, insert the pitch-shifter before a reverb on an aux channel, and send your source to it; the reverb will help to hide any pitch-shifting artifacts. Place a chorus, flanger or rotary speaker emulator directly after the reverb to add further texture without affecting the dry sound, and if this all sounds a little too obvious, try moving the modulation between the reverb and the pitch-shifter.

Basic Bass

The bass parts I usually end up using are warm and simple, with a fair amount of repetition; they underpin the track without demanding too much attention. The sound generally comes from a bass guitar or, as in the example, a simple bass synth that can produce TB-303-style sounds. That said, I’ve also used tuned percussion such as log drums in the past, and an EBow line pitch-shifted down by an octave produces a bowed bass sound on some of my album tracks.

Chorus and compression can add a ‘fretless’ quality to bass guitar, while the sort of tempo-sync’ed tremolo or chopping I discussed earlier can be used to add a rhythmic pulse to just about any bass part. For the demo tune, I used a simple mono synth followed by a phase distortion plug-in to lend it a little FM-like complexity.

Adding Rhythm

For drum and percussion parts I’ll usually gravitate towards world percussion or electronic drums, but there are no hard rules. For this piece, I simply added a little overdrive to an Apple drum loop and then applied top-cut filtering to soften the overall effect. The human ear soon tunes out repetition, so even if your underlying drum loop is repetitive, such processing on one part can help to add variation to the layered percussion parts when the ‘rhythm section’ plays for any length of time. Layering a long percussion loop an odd number of bars in length over a basic drum loop can also often maintain interest.

Mixing & Mastering

The way I work means there’ll inevitably be some processor-intensive tracks in these projects, so I tend to bounce a lot of things down to audio to free up CPU power for mixing. I call it ‘mixing’ but, as with lots of dance music (being in the 70-90 bpm range everything happens rather more slowly than with dance!), you’ll probably find that the tasks of mixing and arranging tend to leak into each other. For example, you may find when setting up a mix balance that you feel a section of rhythm or pad needs to drop out to create a breakdown section, or to give a section more space.

With most of the sonic processing already in place and the arrangement tweaks done, the main challenge is to ensure that all those long delays and reverbs don’t clutter up the mix. Sometimes, it’s simply a case of rebalancing effects levels, but more high- and low-cut filtering may be needed to constrain the effects. For panning, I follow the usual strategies of leaving bass-rich sounds near the centre, and spreading out sounds which play simultaneously and share similar spectral content. Spot effects can sometimes be treated to dynamic panning (using automation or an auto-pan plug-in), but mostly it comes down to getting a good left/right balance and creating a sense of width and space. The subtle differences introduced by all the pitch-correction and modulation mean there’s already a good sense of movement across the stereo image. We’re definitely in the realm of art rather than science here!

As so much of my music is now distributed online, the mixing and mastering usually happens at the same time. Typically I’ll have a loudness meter in place to ensure that each mix hovers around -16 LUFS, but subjective listening tests are still needed to ensure that the track levels and tonality actually feel right. My main processor is my Drawmer 2476 Masterflow hardware box, which includes a three-band variable saturator and a three-band stereo width control, in addition to its more conventional dynamics, EQ and limiting capabilities. My usual setting for this type of music is to narrow the low-frequency width, leave the mids alone and subtly widen the highs. I find that a little emulated tube saturation can also benefit the lows and highs, while keeping the mids clean. For overall compression, I stick with the tried-and-trusted low-ratio, low-threshold combination, skimming only a few dB off the overall level, and with the limiter in place just to catch the occasional peak (set to -2dB to allow MP3 conversion without clipping).

While I’m familiar with my Drawmer unit, there’s no shortage of high-quality ‘make mastering easy’ plug-ins, and you can obviously achieve similar things with them — it’s all about how you use them. My best advice is to keep an eye on the loudness meter to make sure you don’t push things too hard, and to avoid excessive limiting. A couple of plug-ins I’ve tried recently are Soundtheory’s Gullfoss, a type of automatic EQ that can help improve the focus and spectral balance of mixes, and Zynaptiq’s Intensity, which does a similar thing but with a weighting control to focus the processing where you need it most. If I didn’t already have my Drawmer Masterflow, I’m pretty sure that one of these would end up across every mix, as they do lift out detail in a useful way.

Finally, remember to really listen to what’s going on in your mixes. To that end, I find it helpful to hide the screen display or at least to look away, as an arrange page full of blocks is too distracting. That’s why my AES presentation was done using sound only! If you can actually enjoy your own mixes after hearing the work in progress for so long, you know you’re doing something right. But before uploading your tracks for others to hear, it’s always a good idea to play them on a variety of systems and headphones/earbuds — and to forward copies to friends who you know have good ears and won’t just flatter you. That gives you a chance to consider any criticism before letting your creation out into the world!

Audio Examples

Download | 134 MB