To transform multiple takes into truly great vocal tracks, you might need to look further than your DAW’s built‑in comping tools.

One of the only production techniques common to pretty much every hit record nowadays is vocal comping: the process of recording several takes of your lead vocalist and then editing together a master performance from all the best bits. However, I’ve found that project‑studio recordists often don’t make the most of this technique. In this article, I’ll explain my approach to assembling the best possible composite performance from multiple takes.

Take On Me

At the risk of illuminating the blindingly obvious, the most important part of the comping process is the takes themselves. On the one hand, you want enough takes so you get great raw material for each and every phrase; but on the other you want to avoid collecting so many takes that it takes ages to wade through them at the editing stage. My first suggestion is to choose a fixed number of tracks for vocal takes (somewhere between four and eight strikes a good balance), and to check back over those takes as you record, replacing any that seem obviously weaker than the rest. It’s not uncommon that singers need a couple of takes to warm up and really inhabit the part, so those initial passes can often be jettisoned, for instance.

Now, I realise that many DAWs actually have a dedicated take‑stacking facility built into them, allowing you to manage multiple takes within a single track, so why not take advantage of that? Well, although such functions can usefully streamline the editing process, at the tracking stage I find they encourage you to just build up masses of takes indiscriminately, because they usually don’t make it easy to restrict your total take count by going back and rerecording over specific sections of previous takes. So I’d advise against using take stacking while tracking, in order to avoid making a rod for your own back at the editing stage.

A second tip for helping the comping process, especially with less experienced singers, is to work on the song in sections, rather than just doing a series of full‑song takes. A singer’s voice will inevitably tire as the tracking session progresses, so working in sections avoids your having to edit together fresh‑voiced and fatigued‑voice versions of the same phrase. Also, be careful with the first vocal entry of each section you record, because some singers may have difficulty hitting it as accurately (or with as much emotional intensity) as subsequent phrases, simply because they’re approaching it from a standing start. A nifty trick here is to get the singer to sing the beginning of the first phrase a couple of times during the run‑up to the proper entry, because it’s easy to remove those false starts at the edit.

The goal of the tracking stage is to get enough great takes to let you splice together a stellar final performance. Exactly which pieces of each take you choose may be something you decide in the moment while tracking, or as a separate process once the singer’s gone home. Either way, it’s not a bad idea to start your comp of each section from your favourite full‑section take, patching up any weak points from other takes as necessary. This usually seems to give a smoother and more musical end result than adopting a purely patchwork approach right from the outset.

That said, it’s still worth listening through to all the takes at least once while editing, just to make sure you don’t miss any unrepeatable golden moments during otherwise unpromising takes. Those are often the things that listeners remember most of all, so it’s worth ferreting them all out.

Stop In The Name Of Consonants

It’s not enough just to identify all the best take sections, though. You also have to manage the technicalities of stitching them together into a seamless‑sounding master take. After all, the ultimate purpose of comping is to make it sound like the singer just naturally nailed a single perfect performance, so it’s vital that clunky‑sounding edits don’t undermine the illusion. With this in mind, let’s explore some ways you can compile even a ‘jigsaw puzzle’ vocal without it sounding edited at all.

As with house‑buying, the secret to invisible vocal editing is location, location, location. In other words, the most important thing is where you place the edits. Easily the best place for any edit is when the singer’s silent. On the face of it, you might think that means only between vocal phrases, but if you zoom in on any vocal waveform, you’ll usually see that it’s peppered with tiny little pockets of silence that are just as usable for editing purposes. You see, there’s a whole family of consonants called ‘stop‑consonants’, where the tongue or lips momentarily interrupt the flow of air through the mouth. For instance, all the following words have stop‑consonants in them that would easily allow you to edit their first and second syllables from different takes if you wished: ‘apart’, ‘OK’, ‘into’ and ‘richer’.

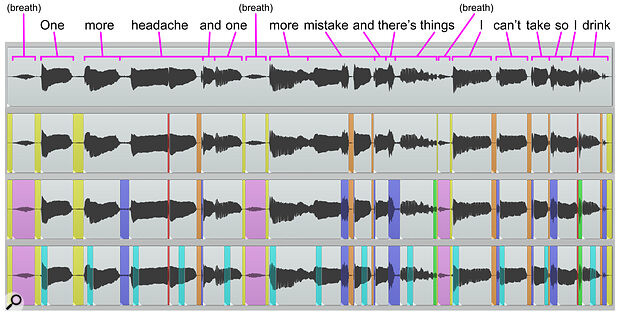

Here you can see a vocal phrase from a song called ‘Sweet Dreams’ by British singer Conor Molloy (https://conormolloymusic.com/). At the top, I’ve indicated where the lyrics fall in relation to the waveform, and then I’ve coloured the three duplicates below to show the various editing locations discussed in this article. In the second lane I’ve indicated silent regions (yellow), short gaps before unvoiced stop‑consonants (orange), and often‑usable edit points before voiced stop‑consonants. In the third lane I’ve added in breaths (pink) and other noisy consonants (orange for unvoiced, red for voiced), and in the fourth I’ve added editing locations that might be masked by a simple four‑beat drum pattern. As you can see, there’s no shortage of possibilities here, even without recourse to more complicated matched‑waveform editing.

Here you can see a vocal phrase from a song called ‘Sweet Dreams’ by British singer Conor Molloy (https://conormolloymusic.com/). At the top, I’ve indicated where the lyrics fall in relation to the waveform, and then I’ve coloured the three duplicates below to show the various editing locations discussed in this article. In the second lane I’ve indicated silent regions (yellow), short gaps before unvoiced stop‑consonants (orange), and often‑usable edit points before voiced stop‑consonants. In the third lane I’ve added in breaths (pink) and other noisy consonants (orange for unvoiced, red for voiced), and in the fourth I’ve added editing locations that might be masked by a simple four‑beat drum pattern. As you can see, there’s no shortage of possibilities here, even without recourse to more complicated matched‑waveform editing.

If you rest your fingers on your larynx while saying each of those words, you’ll actually feel that it briefly stops vibrating for the ‘p’, ‘k’, ‘t’ and ‘ch’ sounds respectively. However, there are also versions of those same stop‑consonants where the vibrations continue uninterrupted, namely the ‘b’, ‘g’, ‘d’ and ‘dg’ in ‘baby’, ‘again’, ‘lady’ and ‘badger’ — so‑called ‘voiced’ stop‑consonants. Leaving aside whether you’ll ever actually encounter a lyric with the word ‘badger’ in it, the voicing of these consonants often fills in the silence preceding them, so they might therefore seem less viable as edit points. In practice, though, the moment just before the consonant sound itself will often be so dull‑sounding (on account of the tongue/lip airway obstruction) that you can still slip an edit point in there without anyone noticing.

For any vocal edit you do, it makes sense to use a crossfade at the edit point, to avoid unwanted clicks should the waveform level be mismatched on either side. For the edits so far, though, you should only need a very short crossfade — a couple of milliseconds should be plenty. Most DAW platforms use curved ‘equal power’ crossfade shapes by default, and that’s also just fine for the moment.

Feel The Noise

Another excellent place to conceal vocal‑comping edits is in noisy signals, because noise is by nature full of fast, unpredictable waveform movements. The most obvious noisy elements in a vocal performance are the breaths, and you can usually edit as freely within those as you can in the mini‑silences that typically sit either side of them. Breaths aren’t all created equal, though, and sometimes a longer 30‑100 ms crossfade may be necessary to avoid any abrupt tonal changes midway through an in‑breath edit.

But breaths are only one of many noise components in most vocal parts. The ‘s’, ‘sh’, ‘ch’, ‘t’, ‘th’ and ‘k’ consonants in ‘us’, ‘show’, ‘each’, ‘too’, ‘think’ and ‘OK’ respectively are all just noise bursts with different tonal and envelope characteristics, and will usually conceal a comping edit just as easily as a breath does. Furthermore, all of these noisy consonants also have voiced versions (the ‘s’, ‘j’, ‘g’, ‘d’, ‘th’ and ‘g’ in ‘easy’, ‘je t’aime’, ‘raging’, ‘adore’, ‘either’ and ‘ego’ respectively) which will frequently hide an edit just as well.

Taking advantage of silences and noise components within the vocal signal should already provide you with a broad range of editing locations — as you can see in the annotated vocal phrase pictured in this article. Where it’s more challenging to get a smooth edit, though, is where you’re trying to switch between takes during pitched phonemes such as vowels.

Match Analysis

There are two main tricks in getting this to work. Firstly, you need to zoom in on the waveforms of the two takes you’re comping together. Pitched notes usually have a clearly defined repeating waveform shape, and if that repetition isn’t maintained smoothly across the edit point, then you’ll need to slide one of the pieces of audio just enough to match things up. (Don’t worry — this shouldn’t have any appreciable impact on the vocalist’s rhythmic feel.)

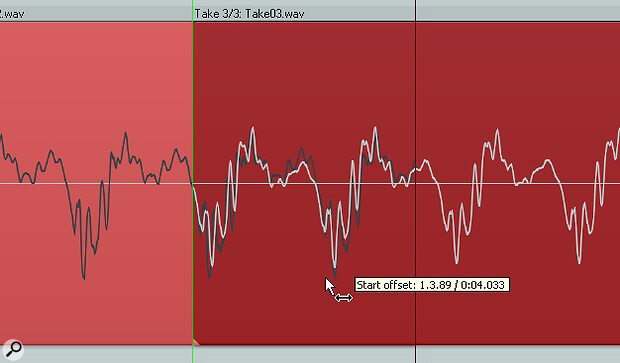

Here you can see an edit point between two takes with a waveform mismatch across it. This will usually sound lumpy even once you add a crossfade.

Here you can see an edit point between two takes with a waveform mismatch across it. This will usually sound lumpy even once you add a crossfade.

Now you can see that I’ve dragged the latter audio region to line up the waveforms...

Now you can see that I’ve dragged the latter audio region to line up the waveforms...

Once you’ve matched the waveforms across the edit, the second trick is to switch the crossfade type to its ‘equal gain’ mode (usually shown graphically as a straight ‘x’‑shaped crossfade) and then extend the crossfade across only one or two waveform cycles. If you keep the crossfade mode set to ‘equal power’, you’ll get a little gain bump during the crossfade that can draw unwelcome attention to the edit. If you get them right, though, matched‑waveform edits like this can be well‑nigh undetectable.

...and now I’ve added an equal-gain crossfade lasting about one and a half waveform cycles. This should give a much smoother edit.

...and now I’ve added an equal-gain crossfade lasting about one and a half waveform cycles. This should give a much smoother edit.

If the note pitches on either side of the edit diverge at all, then the waveform repetition rate will change across the slice point.

Here are a few more tips, in case you’re struggling to get transparent results here:

1. If the note pitches on either side of the edit diverge at all, then the waveform repetition rate (determined by the pitch) will change across the slice point, making it impossible to get a smooth transition no matter how well you try to match the waveform or adjust the crossfade. In this case, the solution may be to pitch‑correct one of the notes off‑line before proceeding.

2. Some consonants and vowels are produced by transitioning between more than one phoneme. So, for instance, the word ‘power’ can be broken down into an opening ‘p’ stop‑consonant followed by three vowel phonemes: ‘a’, ‘oo’ and ‘er’. Because matched‑waveform edits rely on maintaining a repeating waveform shape through the slice point, it’s better to place the edit during a steady‑state vowel phoneme, rather than during the transition between the phonemes. So, in our ‘power’ example, you’d rather edit during the ‘a’ or ‘er’ phonemes than during the ‘w’ consonant (which comprises a swift ‘a‑oo‑er’ three‑phoneme transition).

3. Don’t forget about ‘m’ and ‘n’ consonants, which can be edited in much the same way as sustained vowels — although, again, it’s best not to place your edit where they’re transitioning to or from another phoneme.

Behind The Mask

All the editing techniques so far have relied on the inherent nature of the vocal signal itself, but most modern productions also provide plenty of options for hiding even quite lumpy‑sounding vocal edits behind the high‑energy transients of drum and percussion instruments. The signal peaks these rhythm elements generate cause strong perceptual frequency masking, so if you place your vocal edit point strategically, it’ll be obscured by the masking effect.

If you want to hear quite an obvious commercial example of this, have a hunt on YouTube for the a cappella mix of Christina Aguilera’s ‘Genie In A Bottle’, and you’ll hear that there’s really quite a clunky edit at the start of the word “waiting” at around 0m 20s. Within the final mix, though, that edit is rendered completely inaudible by the kick drum that plays back at the same time.

This trick isn’t exclusively for use with drums, either. Other rhythm instruments such as funk guitar or rock piano can be just as effective at masking vocal edits if they’re loud enough in the mix.

Take Another Listen

If you use the techniques in this article carefully, you should end up with a comp that sounds as if it’s just a single, live take of the lead vocalist on their best day ever. I have one final tip, though. It’s easy to get too close to the process while editing, and lose your objectivity about whether your edits sound any good or not. Before you sign off on the edit, then, listen through to the whole song from somewhere else in the room (perhaps on a different playback system) and without looking at your screen at all. If all you hear is the performance, and not the edits, that’s probably the clearest sign that your comping work is done!

Online Resources

To support this article, I’ve set up a special resources page on my website, where you’ll find audio demonstrations of the editing techniques discussed in this article, downloadable multitracks with uncomped vocal takes (for editing practice), and links to further reading.