The author checking a master on his Audeze headphones. Sometimes a change of perspective reveals that a drastic EQ move wasn’t necessary after all!

The author checking a master on his Audeze headphones. Sometimes a change of perspective reveals that a drastic EQ move wasn’t necessary after all!

Mastering is not an extension of mixing. It requires its own skill set — and, above all, a philosophy of “first do no harm”.

We often think of mastering as applying the final touches. But sometimes, the most powerful move is doing nothing at all. Mastering, in my experience, is as much about knowing when to intervene as it is about technical finesse. By the time a mix reaches the mastering stage, most of the big decisions have been made. It’s tempting to think that one last tweak — the final five percent — might turn a good song into a great one. But often, the real job is resisting that urge. It’s vital to understand which tiny adjustments truly serve the music, and which might rob it of its soul.

Mastering teaches patience. We remind ourselves that our primary mission is not to fix the mix or showcase our own skills, but to facilitate the artist’s vision. Early in my career, I was eager to sculpt and polish every track. Over time, I learned that great mastering often looks like doing nothing at all. The best masters tend to disappear. The goal is a final product where the music speaks, not the engineer.

The Art Of Restraint

In mastering, less is almost always more. I follow a simple rule: change as little as necessary. If it isn’t broken, don’t fix it. Perhaps a mix has a boomy low end or an overly bright top, but sometimes it doesn’t. Sometimes the first instinct is to reach for a big EQ boost or heavy compression, but good mastering is more about subtle shifts. It’s like adjusting the colour palette of a film, rather than changing the edit itself.

In mastering, less is almost always more. I follow a simple rule: change as little as necessary. If it isn’t broken, don’t fix it.

I recall an early case with an indie ballad — a whisper‑quiet song about heartbreak and loss. The mix engineer gave me a delicate track with soft guitar strums and vocals so intimate you could hear the artist’s breath. It had a gentle beauty, but the vocalist’s breath was a tiny bit loud, and there was a faint hiss in the background. In the studio, I found myself turning up the volume to really feel the music, and that background noise became more apparent. The instinct was to apply a noise gate or offline noise reduction. But doing so would have snatched away the song’s intimacy. Instead, I took a much gentler approach: a surgical parametric cut on the loudest breaths, and a very light downward expansion that left plenty of breathing space. The final master still had a bit of ambience and grain, but without the distracting hiss.

In mastering, less is often more. In this case, a cut of 0.5dB at 7.4kHz made all the difference.

In mastering, less is often more. In this case, a cut of 0.5dB at 7.4kHz made all the difference.

That moment taught me a lot about the final five percent. If I had cranked a broadband compressor or aggressively gated every noise, the track might have become technically cleaner, but it would have sounded sterile. The emotional resonance would have been lost. For that song, I learned that patience is more valuable than heavy‑handed editing. Trust the musical intent: sometimes an imperfection in the mix is part of the fabric of the song. But restraint isn’t always obvious in practice — especially when a mix arrives with more apparent flaws.

When Fixing Hurts More Than It Helps

Not all sessions are so subtle. Some mixes have obvious issues: a tilt towards harshness, muddiness in the mids, or an overbearing low end. The challenge is deciding when to step in. Remember that mastering is the final polish, not a remix. If something feels fundamentally off, ask if it might be a mix problem in need of revision.

One harsh lesson for me came with a rock track featuring a lead vocal from a vintage tube mic. It had grit and character — exactly what the band loved — but at higher volumes the vocal became rough around the edges. By the time I got the bounce, the highs were already hitting the ceiling. My first thought was to reach for an EQ to tame the offending frequencies. But big cuts in the mids could rob the vocal of its warmth, and a heavy de‑esser would flatten the tone too much. I had to judge which was a more important thing to chase: technical polish, or the character that the band adored.

In this case, the grit was part of the charm. Rather than massacre it, I opted for a very gentle shelving EQ and a hint of parallel compression to add presence without smothering the dynamics. The result was a vocal that still sounded raw and alive, but sat better in the mix. The band was thrilled, and the vocal retained its soul. That session taught me that sometimes trying to ‘fix’ what’s already characterful can do more harm than good.

Trust Your Ears, Not The Meters

Another turning point came with a dance mix plagued by low‑end woes. The kick drum was solid, but the sub frequencies around 30Hz were overwhelming, rumbling through the entire track. The mix engineer said it was subtle, but once I heard it, I knew it needed attention. At first I thought a quick high‑pass filter or narrow cut might solve it. But I worried: would a fix at 30Hz mask a deeper issue, and could it drain the track’s energy?

So I tried something different: a subtle shelf EQ at 40Hz. It cleaned up the rumble just enough, without sucking the life out of the kick. The difference was night and day: the track lost its muddiness but still felt powerful. I was tempted to stare at the analyser, which showed a flat bottom end, apparently perfect. But I reminded myself that listening is believing. On speakers, the track still slaps. On headphones, it still thumps. The fix worked, not because the meter smiled, but because it sounded good.

The lesson here is simple: trust the music more than any meter reading. Engineers can obsess over flat frequency response, but listeners feel impact more than they analyse waveforms. A little precision EQ’ing in context can do wonders, but only if you let the sound be the final judge. In that session, I merely nudged the mix and let the groove take care of the rest.

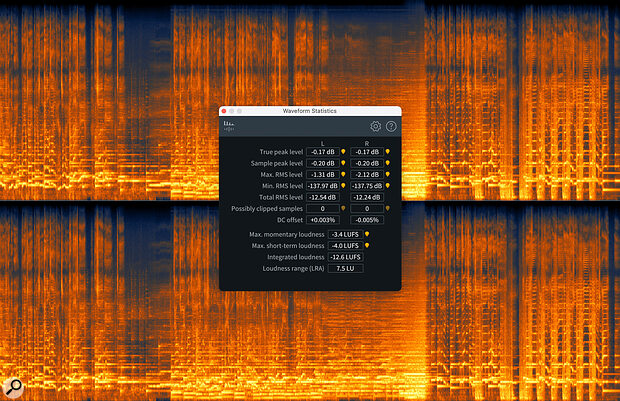

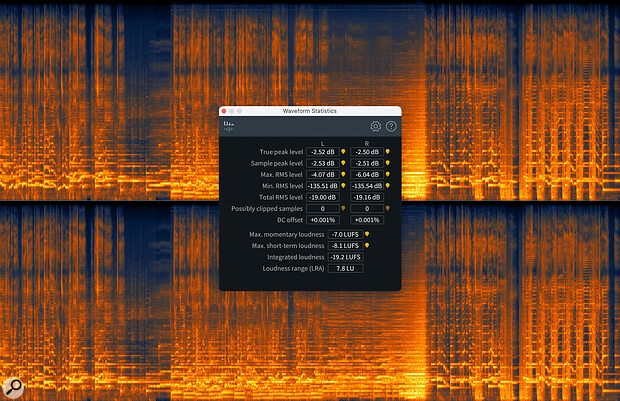

Before (top) and after: mastering has largely preserved the dynamic range of the mix whilst making it appropriately loud for distribution.

Before (top) and after: mastering has largely preserved the dynamic range of the mix whilst making it appropriately loud for distribution.

The Psychology Of Over‑processing

Beyond the gear and meters, the trickiest part can be mastering your own mindset. Working on the final five percent is as much psychological as it is technical. When you’re close to done, it’s easy to become overly self‑critical. I’ve sat through countless mastering sessions thinking, “What if I can make it just perfect?” — only to discover that this mindset can lead to diminishing returns. Keep redoing the take and you’ll chase the magic right out of it. The same can happen in mastering.

The urge to perfect can sometimes sterilise the very thing that gives a song life.

The urge to perfect can sometimes sterilise the very thing that gives a song life. Listen closely to Keith’s guitar part in ‘Satisfaction’ and you can hear stompbox clicks and tiny slips in timing. No one fixed them, and thank God they didn’t. That rawness is part of the feel. It’s proof that sometimes the best move is to leave the mess alone.

If I find myself tweaking and re‑tweaking, I take a break. I might listen in my car, through earbuds, or on the phone speaker. Maybe I need some silence and a walk outside. Usually, I realise the music still stands strong, and any ‘problems’ weren’t as bad or as difficult as I thought.

Communication still matters, even from a distance. I often ask artists or mixers, “At what point does it feel right to you?” If they reply saying they got goosebumps or found themselves tapping along, that’s usually a good sign we’re close. Mastering is a support role. If the artist starts pushing back on every small change, that’s often your cue to stop. Getting an outside perspective reminds me that sometimes, a bit of imperfection is fine if it means preserving the song’s emotion.

When To Step Back

Ultimately, deciding what to fix comes down to musical purpose. If an issue is truly hindering the song’s emotion or clarity, it deserves attention. But if it’s merely a technical quibble, consider letting it be. I stick by a simple rule: only make changes that serve the music.

For instance, say a guitar track in the mix is a hair muddy. I could carve it up with surgical EQ or multiband compression, but that might sacrifice warmth and body. Sometimes it’s better to live with a small amount of mud than end up with a brittle sound. Similarly, if a vocal is a touch quiet, I might ride its level or do subtle compression, but blasting it forward by cranking everything else up could make the track feel unnatural.

Wield your tools with intention, not reckless abandon. Digital gear lets you make precise moves, but music isn’t an equation — it’s about feel. By stepping back and thinking in musical terms, you often find that what seemed like a problem on the screen is less noticeable in the song.

Digital gear lets you make precise moves, but music isn’t an equation — it’s about feel.

Thinking In Context

Even when I’m mastering just one track, I try to imagine the bigger picture. How will this sit in a playlist? Will it be part of an EP or a full‑length album? The final five percent isn’t just about what a song needs in isolation. It’s about what it needs to survive in the world for years to come. A track might sound rich and full on its own, but placed back‑to‑back with others, it can suddenly feel overbearing or flat. I’ve had cases where a bass‑heavy mix felt great solo, but disrupted the pacing of an album. Using my tools, I can transfer that bass energy to other areas of the track where it adds body. Other times, I’ve dialled back the brightness on one song, not because it was ‘wrong’ but because it needed to yield space to what came next.

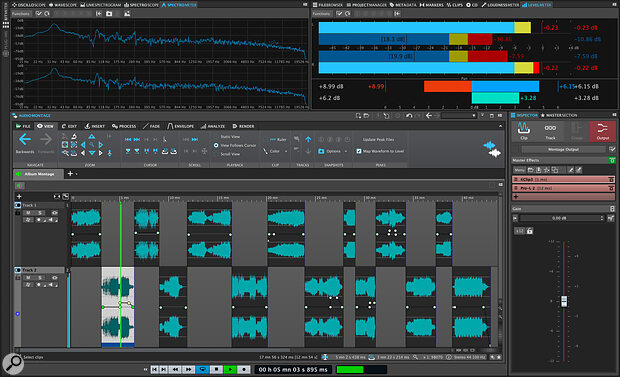

It’s vital to consider the context when working on any individual track. Here we see an entire album laid out in WaveLab’s Montage view.

It’s vital to consider the context when working on any individual track. Here we see an entire album laid out in WaveLab’s Montage view.

This isn’t a new idea. In the vinyl era, sequencing and tonal flow were fundamental, and engineers would shape sides of a record to feel cohesive, not just sonically but emotionally. Loudness had to be managed carefully across the side to avoid inner groove distortion. Even in the CD era, where format limits eased, mastering engineers often treated the album as a journey, ensuring each track spoke to the next. Today, streaming playlists have become the new battleground for continuity, with songs living in dynamic, algorithmically driven environments. But the goal remains: cohesion. Mastering isn’t just polishing: it’s sequencing, shaping, and creating a flow that feels intentional. Whether you’re finalising an album or just hoping your single lands gracefully between two others on Spotify, context always matters.

Mastering is ultimately an act of service to the song. And service sometimes means knowing when to stop tinkering.

Serving The Song

Mastering is ultimately an act of service to the song. And service sometimes means knowing when to stop tinkering. The final five percent of any project is as much about judgement and respect as it is about EQ curves and limiters. In my career, I’ve found that letting the music breathe often yields masters that resonate far longer than the loudest possible version ever could. If listeners feel magic in the song — a goosebump, a memory, a thrill — then the mastering engineer has done their job. We can spend hours finessing frequencies, but if the end result still moves someone, you’ve succeeded.

So, the next time you’re teetering on that razor’s edge, ask yourself: is this really serving the music? Or just serving my need to feel useful? If it’s the latter, maybe it’s best to keep your hands off and let the song shine on its own. If it moves someone, you’ve done your job.

Alexander Wright is a mastering engineer based in Seattle and the author of The Wright Balance Method: A Philosophy Of Mastering, Listening, And Letting Go.

Learn more at alexanderwright.com

A Few Simple Rules I Try To Follow

- Fix with purpose: Use EQ and compression only when it serves the song’s emotion. Don’t ‘correct’ a sound that is part of the vibe.

- Be minimal: Often, the smallest tweaks have the biggest impact. A tiny EQ nudge or subtle dynamic change can go a long way.

- Trust your ears: Meters and scopes are tools, but if it sounds right in context, it probably is. Let what you hear guide you more than any readout.

- Communicate: Collaboration with the artist and mixer is vital. They know the vision — make sure your changes align with it.

- Take breaks: Rest your ears. A fresh listen can reveal whether the track was already fine, or if you truly needed that tweak.