Izzat Majeed single‑handedly resuscitated Pakistan's moribund music scene — and built a state‑of‑the‑art studio to capture the results.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the city of Lahore was the centre of a thriving film industry, thanks in no small part to the musicians who generated many memorable soundtracks for 'Lollywood' films. However, under the ultra‑conservative rule of Muhammad Zia ul‑Haq between 1978 and 1988, the city's cinemas and film studios were decimated, leaving session players with little regular work and fewer opportunities to perform as openly as they once had. Lollywood — and many of its musical stars — never recovered.

Just over a decade ago, Pakistani businessman Izzat Majeed began to realise a personal dream of tracking down and committing to tape the surviving musical stars of Lahore's once‑thriving film industry. Izzat grew up in Lahore during the heyday of its film industry, which, at its peak, was producing over 100 musicals a year. Izzat's father was Lollywood producer Mian Abdul Majeed. As well as exposing his young son's ears to his country's Izzat Majeed introduces the Sachal Studios Orchestra on stage at the Alchemy Festival. traditional classical music, Mian also played him American jazz recordings and took him to concerts by eminent US jazz icons when they touched down on Pakistani soil as part of Dwight D. Eisenhower's 'Jambassadors' overseas tours during the late '50s and early '60s.

Izzat Majeed introduces the Sachal Studios Orchestra on stage at the Alchemy Festival. traditional classical music, Mian also played him American jazz recordings and took him to concerts by eminent US jazz icons when they touched down on Pakistani soil as part of Dwight D. Eisenhower's 'Jambassadors' overseas tours during the late '50s and early '60s.

"I was eight years old when I saw Dave Brubeck in '58, six years old when I saw Dizzy Gillespie in '56 and I think I saw Duke Ellington in '63 or something like that,” explains Izzat. "I vividly remember Dave Brubeck. He hadn't recorded 'Take Five' then, but I think I got a shot in the heart and the mind when I saw him. And at the same time, I had our own music and classical expression.”

Izzat's personal project achieved much wider recognition in 2011, when a record he produced became a global sensation. Sachal Jazz: Interpretations Of Jazz Standards & Bossa Nova by the Sachal Studios Orchestra shot to the summit of the iTunes World Albums chart in the US, the UK and Canada, while gracing the top 10 in numerous other territories. The album was made up of ambitious and ingenious arrangements of jazz standards which utilised Eastern instruments such as the sitar, sarangi, sarod, dholak and tabla as well as heart‑warming layers of traditional Lahori strings. The video to Sachal's version of the Dave Brubeck Quartet's 'Take Five' — a cover The control room at Sachal Studios. which Brubeck himself loved — has garnered hundreds of thousands of views since it was first posted online.

The control room at Sachal Studios. which Brubeck himself loved — has garnered hundreds of thousands of views since it was first posted online.

For the last few years, events have started to really snowball for Izzat Majeed and the Sachal Studios Orchestra. The troupe have played several concerts in New York with jazz legend Wynton Marsalis, sold out the Queen Elizabeth Hall in London and recently released their second jazz‑fused long player Jazz And All That to yet more critical acclaim. This is just the beginning of a really quite remarkable story.

The Folk Revival

In 2002, Majeed — who had by now accrued his own fortune working in Europe and the Middle East — began making recordings with ex‑Lollywood players and composers, as well as a number of folk musicians he had either painstakingly tracked down or been introduced to since he commenced his project of discovery. These albums were essentially more classical or 'symphonic' takes on traditional Pakistani folk music, a mixing of styles that Izzat has continued to champion across multiple releases on his Sachal Music label.

"What I have done for folk music is I've tried to bring it into the symphonic and harmonious arrangement structure,” says the entrepreneur. "Many people say, 'Oh, you've ruined it, this is not folk music!' but one has to go on, you know. You can't just play on a clay pot and a broken string and call it folk music. There was a time when it was like that because there was nothing else, but nowadays we need to make it alive for the younger generation and for the world at large.”

Majeed has found that, unfortunately, there are now very few traditional folk musicians left keeping the flame alive in and around Lahore. "I think there may be germs of folk music in the religious rural areas which we know nothing about, but not all of them reach the cities to get recognised,” explains Izzat. "But sometimes I'll go to an area where my friends are and you just walk in and you hear music. A guy comes in and sings or plays an instrument. Some play fantastic, handmade percussion for example. In other countries, that guy would be immediately taken up and people would say, 'OK, let's tell the world what you're doing!' but that doesn't happen. Very great folk musicians have gone unheard.”

One over‑arching — and ultimately game‑changing — problem Izzat and his team had in those early years was finding high‑quality recording facilities in Lahore. "Those studios we went to basically just had small machines, a tiny recording room and a few small cubicles for other players,” says Majeed. "The recordings were pretty good, actually, but the atmosphere was always very suffocating. That's when I decided 'This won't work, I need to build our own studios!'”

Majeed consequently Izzat Majeed was persuaded by his musicians that Sachal Studios must be built in downtown Lahore. The chosen site was part of a down‑at‑heel car parts market. decided to invest around £2 million of his own money into building Sachal Studios, a vast brand‑new studio complex in central Lahore, which duly opened its doors in 2005 (see box). Many of the musicians whom the entrepreneur discovered are even paid a retainer by the studio to enable them to focus on their own playing as well as teaching their traditional techniques to the next generation.

Izzat Majeed was persuaded by his musicians that Sachal Studios must be built in downtown Lahore. The chosen site was part of a down‑at‑heel car parts market. decided to invest around £2 million of his own money into building Sachal Studios, a vast brand‑new studio complex in central Lahore, which duly opened its doors in 2005 (see box). Many of the musicians whom the entrepreneur discovered are even paid a retainer by the studio to enable them to focus on their own playing as well as teaching their traditional techniques to the next generation.

All That Jazz

After Izzat Majeed invested a staggering £2 million of his own personal fortune in Sachal Studios, he and his production team — which included chief engineer Munir Kokab and late arranger Riaz Hussain — commenced recordings at the new complex in 2005. It was in 2008 that Izzat decided it would be interesting if his sizeable group of in‑house musicians dipped their multi‑talented hands into a few jazz standards. The majority were not even familiar with jazz as a musical genre.

"I just thought, 'Let's see what I can do with "Take Five”, and it was really just a labour of love for me really,” recalls Majeed. "I never thought that it would be going around the world or topping the charts or things like that. When the musicians discovered what jazz is, it turns out they realised it was very close to our classical structure. You have to decide the scale and you have to decide the rhythm and the structure. Then, having done that, you play around what the basic structure of that particular song is and you have your free time. Obviously, you stay within a certain circle and then you come back. This is exactly what jazz does too.”

London‑based engineer Christoph Bracher, who was heavily involved in the recording and mixing of both Sachal Studios Orchestra jazz fusion albums, played a key role in the very first track that was cut, Dave Brubeck's immortal 'Take Five'. "I basically created a backing track for 'Take Five' and then we sent it to Lahore,” explains Christoph. "I actually learned to play it on the grand piano in my house and I recorded it and then created an arrangement Studio construction, Pakistan‑style... and created a format with a drum guide and things like that. Then we sent that to Pakistan and they kept overdubbing on it. That was the starting point of Sachal Jazz. That was the first track. I found the whole concept very exciting because I've worked in Asian music for a very long time. It was very interesting when this kind of fusion came into existence, and some of the tracks I think have turned out quite stunning.”

Studio construction, Pakistan‑style... and created a format with a drum guide and things like that. Then we sent that to Pakistan and they kept overdubbing on it. That was the starting point of Sachal Jazz. That was the first track. I found the whole concept very exciting because I've worked in Asian music for a very long time. It was very interesting when this kind of fusion came into existence, and some of the tracks I think have turned out quite stunning.”

'Take Five' is a case in point and it was this innovative arrangement, spearheaded by Balu Khan's hypnotic tabla and Nafees Khan's supreme sitar lines, which created such a huge stir across the music world, helping put the Sachal Studios Orchestra firmly on the map. A copy of the track was even sent to Dave Brubeck who faxed words of praise to the Sachal team. "This is the most interesting and different recording of 'Take Five' that I've ever heard,” exclaimed Brubeck, before communicating the following message at a later date. "Listening to this exotic version of 'Take Five' brings back wonderful memories of Pakistan where my Quartet played in 1958. East is east and west is west, but through music the twain meet. Congratulations!”

"I was very excited for a guy like Brubeck, who almost changed the structure of jazz rhythm, to say that,” enthuses Izzat. "But, you know, the really strange thing about 'Take Five' when I was young was that all these small shops in Lahore would be playing it and it just took off. It was played a lot on the radio and any place you'd go to, there it would be. 'Take Five' would be played and that was very, very strange. People didn't know what it was, they didn't know it was jazz... but they just loved the whole thing.”

Sadly, Dave Brubeck passed away in December 2012, just a year after the Sachal Studio Orchestra's version of 'Take Five' had taken off across the globe. The Jazz And All That album is dedicated to his memory.

Amateur Arrangements

Izzat Majeed has produced both Sachal Jazz albums so far, and he also played a significant role in arranging them. The first album was co‑arranged with Riaz Hussain while the second, following Hussain's passing, was arranged with the assistance of Riaz's son, Nijat Ali. "I used to sit down with Riaz, who was a wonderful human being, and now I sit down the same with his son and I say, 'These are the instruments I want,'” explains Majeed. "I say to the musicians, 'Give me variations of what we can do,' and, ...Paired with a more orthodox approach to interior design. of course, I want the same with the rhythm structure, but the rhythm guys are very stubborn. You know, you have to really argue with them and say, 'This is not working, do something else.' We keep on working like that with suggestions going to and fro. The arrangement is a dialogue between me and the musicians. It can't be a monologue. But the thing is, it's a family, so we're not afraid of challenging each other. The end product is really a joint venture, which I think makes it better. Sometimes, things don't work. Sometimes, I'll think I've been dreaming about a certain sound or instrument and it'll take weeks for it to really mesh into the arrangement and then you realise that it's not going to work. That happens all the time.”

...Paired with a more orthodox approach to interior design. of course, I want the same with the rhythm structure, but the rhythm guys are very stubborn. You know, you have to really argue with them and say, 'This is not working, do something else.' We keep on working like that with suggestions going to and fro. The arrangement is a dialogue between me and the musicians. It can't be a monologue. But the thing is, it's a family, so we're not afraid of challenging each other. The end product is really a joint venture, which I think makes it better. Sometimes, things don't work. Sometimes, I'll think I've been dreaming about a certain sound or instrument and it'll take weeks for it to really mesh into the arrangement and then you realise that it's not going to work. That happens all the time.”

In essence, much of Izzat Majeed's approach to production is based on gut feeling. "I've never had any clue what music is and I still don't. I can't write music and have no idea what scales are and things. It's just what I hear and what I want to create that gives a certain peace of mind and, at the same time, an exhilaration of how the song has come out.”

"Izzat describes himself as an enthusiastic amateur,” says Abbey Road engineer Sam Okell, who recorded a few additional overdubs in London for both Sachal Jazz records as well as mastering the latest. "And especially with the strict complex structures of this kind of Pakistani music, he'll just say, 'I don't really understand any of that but I know what I like.' And he is very succinct and direct in saying what he does and doesn't like. Left to right: engineers Munir Kokab, Sam Okell and Samuel Suleman Waheed in the Sachal Studios control room. He'll normally have an idea about something and we will try it. For example, I remember one morning he just came in with one of those slinky spring things that go down the stairs and said, 'This is the sound I need on this track.' I thought he'd totally lost it, but then he got, I think, Chris Wells to play the percussion, and he started playing it and the slinky became the main sort of pulse on this track. He loved that!”

Left to right: engineers Munir Kokab, Sam Okell and Samuel Suleman Waheed in the Sachal Studios control room. He'll normally have an idea about something and we will try it. For example, I remember one morning he just came in with one of those slinky spring things that go down the stairs and said, 'This is the sound I need on this track.' I thought he'd totally lost it, but then he got, I think, Chris Wells to play the percussion, and he started playing it and the slinky became the main sort of pulse on this track. He loved that!”

Crossing Continents

While the majority of the instruments on the two Sachal Jazz albums were laid down at Sachal Studios in Lahore, quite a few overdubs were also recorded in London, variously by either Sam Okell or Christoph Bracher at Abbey Road, The Conference Room or Assault & Battery. "The basic recordings are done in Lahore,” explains Izzat Majeed. "And then we sort of embellish them here in London because we have instruments and players here that we don't have in Pakistan. That's the relationship, but the basic core has already been done in Lahore.”

For example, on last year's Jazz And All That album, the violins, sitar, cellos and percussion, including tabla and dholaks, were all laid down in Lahore. Meanwhile, Western instruments such as piano, trumpet, flugelhorn, bass guitar, harmonica, harp and guitar were overdubbed in London.

A beautiful piano was purchased for the studios in Lahore, but it is not always particularly playable, as Sam Okell, Samuel Suleman Waheed and Munir Kokab discuss mic placement for sitar player Nafees Ahmad. Christoph Bracher explains: "They did buy a Steinbach upright piano there, which I advised against, for the simple reason that there's hardly anybody in Lahore who can tune a piano! And, of course, it gets very humid there, and so they run the AC in the room, so the thing is always out of tune when you get to it.”

Sam Okell, Samuel Suleman Waheed and Munir Kokab discuss mic placement for sitar player Nafees Ahmad. Christoph Bracher explains: "They did buy a Steinbach upright piano there, which I advised against, for the simple reason that there's hardly anybody in Lahore who can tune a piano! And, of course, it gets very humid there, and so they run the AC in the room, so the thing is always out of tune when you get to it.”

The Lahore sessions are overseen by Sachal's chief engineer Munir Kokab and his assistant, Samuel Suleman Waheed. Sachal's Sameer Khan — who is based in London, where he assisted Christoph Bracher on the Jazz And All That overdub sessions — has also spent a significant amount of time at the studios in Lahore, where both he and Christoph have had the chance to  Key members of the Sachal Studios Orchestra also include tabla player Ballu Khan aka Ijaz Hussain (top), and sarangi player Kamal Sabri.observe Munir Kokab's miking techniques up close.

Key members of the Sachal Studios Orchestra also include tabla player Ballu Khan aka Ijaz Hussain (top), and sarangi player Kamal Sabri.observe Munir Kokab's miking techniques up close.

"Munir is a very experienced sound recordist,” Sameer tells us. "He's been recording all the greats, like Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, for over 30 years. In fact, there isn't anyone he hasn't recorded! He uses a variety of miking techniques. For strings, he has a sort of Decca Tree miking set up in the larger room with two [Neumann] U87s in the X‑Y position. He'll record the strings in different passes so it kind of builds up, but I think he'll also change the position of the mics so he hasn't got a set pattern every time.”

"The strings are all recorded in our biggest room,” adds Munir himself. "We do multiple takes to build up the string texture as if there was a whole orchestra playing with first violins, second violins, violas and cellos. Flute, sitar, sarangi, guitar and sarod were all recorded in booths. I felt that there should be as much separation as possible, so that there would be more options to play around with in the final mixing. The rhythm section — tabla, dholak, mardang, naal — almost always nailed it on the first take... and they were generally recorded individually, but sometimes together if the feel of the song required it.”

Flute, sitar, sarangi, guitar and sarod were all recorded in booths. I felt that there should be as much separation as possible, so that there would be more options to play around with in the final mixing. The rhythm section — tabla, dholak, mardang, naal — almost always nailed it on the first take... and they were generally recorded individually, but sometimes together if the feel of the song required it.” Christopher Bracher (right) recording guitarist John Parracelli.

Christopher Bracher (right) recording guitarist John Parracelli.

"You'll quite often have 16 tracks of strings or something, because they usually do several lots of overdubs,” says Christoph Bracher. "You know, the whole orchestra records on two tracks and then it records again on two tracks then several more times on two tracks and you can have as many as eight or even 12 string overdubs. That's how you get the sound. You have 25 string players and then they overdub eight times. It does make sense.”

"They do get a very sort of bright and powerful and phasey string sound,” adds Abbey Road's Sam Okell. "They track these 20 or 30 guys — who are in a relatively small, bright space — and, after tracking them 10 or 12 times, you're getting the sound of three or four hundred musicians, in effect. They go on until six in the morning sometimes. I don't know if that approach comes out of Asian film music but I know that's one of Izzat's references. They certainly love the power of the strings coming in and having such an impact and being so overwhelming.”

Sameer and Christoph both recall that Munir's One of the hallmarks of a Sachal production is the heavily layered strings, sometimes overdubbed as many as 12 times. favoured miking technique for traditional percussion is placing two DPA 4011s in an X‑Y position above each instrument. For sitar, an AKG C414 is positioned above the main body while a DPA 4011 is placed on the upper fretboard. The sarangi and the flute are close‑miked with either an AKG C414 or a DPA 4011.

One of the hallmarks of a Sachal production is the heavily layered strings, sometimes overdubbed as many as 12 times. favoured miking technique for traditional percussion is placing two DPA 4011s in an X‑Y position above each instrument. For sitar, an AKG C414 is positioned above the main body while a DPA 4011 is placed on the upper fretboard. The sarangi and the flute are close‑miked with either an AKG C414 or a DPA 4011.

Developing Themes

As can only be expected with albums made up of so many separate recording, tracking and overdub sessions, both Sachal Jazz albums necessitated a hefty amount of work when it came to the mixing process. Aside from the track 'Monsoon', which was recorded back in 2010 and mixed by Sam Okell, the rest of the songs on Jazz And All That were mixed by Christoph Bracher at the Assault & Battery studio in London's Willesden Green, with Sameer Khan assisting. The overdubbing sessions that Christoph oversaw at Assault & Battery were always undertaken with the mixing process very much at the forefront of his mind.

"What happened was that basically all the ethnic instruments would be recorded and tracked in Pakistan,” explains Bracher. "And the string sections and often the bass parts would be recorded there too, and the rough mixes would be sent over to us. Sometimes we'd replace the bass parts. And then piano and non‑ethnic percussion and any other jazz parts like guitar were recorded by us in London. The pianist Steve Lodder's playing is absolutely happening, and Chris Wells, who is a great player, did all of the percussion overdubs.

"I tried to lay the studio sessions out so we could overdub a few people together. We might have had bass and drums or bass and piano together on a few songs, or bass and guitar together on a few songs. Basically, we overdubbed the jazz part in London. We had a harp player on a few tracks too. We'd get a few takes and try to make the most of them, choosing sections that we thought were most suitable in terms of supporting the track. Sometimes, Izzat would choose something and then you would have the job of making it work, which could be very little work or it could be a lot of work. And then, of course, you have sections in the song that repeat and you repeat a part so that it becomes part of the arrangement. I mean, that's the same in all the songs, really. You might have a bass riff in one particular section which you then take and put that into the same section somewhere else in the song and then, you know, it develops into something. It was all a bit of a jam because all of those musicians were good at jamming. You don't want to wear them out and you want them to be creative, which means you get them to do a few parts until they've got a nice feel and then you try to take all the nicest bits and assemble them together into something that is more than what was actually played. That is the beauty, of course, of working with a click track.”

Around three weeks were spent mixing the very varied 12 remaining jazz‑fused tracks on Jazz And All That. From the Pink Panther theme' to Brubeck's 'Blue Rondo à La Turk', from 'Eleanor Rigby' to REM's 'Everybody Hurts', each ambitious arrangement tells its own story. However, all involved tend to agree that 'Blue Rondo...' was the most ambitious of all the tracks attempted by the Sachal Studios Orchestra. "The click track for 'Blue Rondo...' was extremely complex,” says Munir Kokab. "Apart from 9/8, there are different time changes across the whole song.”

"It's definitely one of the most complicated tracks,” concurs Sameer Khan. "We were recording musicians here [in London] for hours trying to work out how many beats were in this section and how many beats in that section. I think people really enjoy the complexity though. I was trying to do a tempo map and all these boring things on the computer but just couldn't do it so I had to do it by listening, counting how many bars and that sort of thing. It's my favourite one I think after 'Take Five'.”

Appreciated Everywhere But Home

The story of Izzat Majeed and the Sachal Studios Orchestra is truly a remarkable one, and plans are already well underway for the next chapters in this inspirational tale. Sameer Khan is due to convert the Lahore studios over to Pro Tools at some point in the near future, while songs and arrangements are also currently being shortlisted for what will be the third Sachal Jazz album. However, despite the critical acclaim and impressive sales of the first two albums across the Western hemisphere, it would appear that, for the time being at least, there is no real market for the recordings in their native home of Pakistan. Sachal's internal marketing effort certainly hasn't been helped by the fact that YouTube has remained banned in the country ever since the posting of the highly controversial 'Innocence Of Muslims' trailers back in 2012.

"With the Talibanisation of culture, our classical music is almost dead,” explains Izzat. "The only music that survives is from our younger generation, God bless them, and they make some really good music, but it's not our music. The other thing is that there is a tornado of plagiarism. You throw a few CDs into the market and the next day, they're available at 2p from anywhere you like. So, it's not a profitable thing [in Pakistan] but we will keep doing it. There's a lot of talent about and we have proved that these great, great players in their '60s and '70s are still great. They are really happy and now I think they've come alive again. This is my greatest happiness and it's the best thing I've ever done.”

Tracking Down Talents

After decades spent in the musical wilderness both during and following Muhammad Zia ul‑Haq's reactionary regime, it is probably safe to say that many Lollywood musicians never thought they would see the day when their music would be widely appreciated again. Izzat Majeed's project changed all this, and he couldn't have been more overjoyed as more and more session players began appearing.

"It was difficult to get hold of them because the great masters were quite absent,” says Majeed. "With ul‑Haq's dictatorship and what I would say was a very direct interpretation of religion, everything altered. Films went down and television and radio were not as keen on classical music or on promoting music at all. Gradually, it all died and so our great musicians, our great masters had to take very menial jobs to survive. One of the greatest cello players was running a tea stall! But we found that the senior players, when they realised that there was a serious effort being made to rejuvenate the music, they came out. They are really great players and, once that happened, the whole circle was revived, gradually more came along and then the younger generation came along. When we started, we could barely find five or six violins but today we have 45. And the master who had the tea stall has now trained three young people to play the cello so that's great news. We now have a good string section and there'll be another lot ready soon. Everybody's having a great time.”

Izzat even bought new instruments for many of the musicians as and when he discovered them. "I got them a lot of instruments from here in London because their violins had broken and their cellos were gone,” explains Izzat. "I took a lot of stuff over and they were really happy with that. We took the grand master three new cellos and you should have seen his face. He was crying and he was hugging those cellos!”

Building Sachal Studios

When he decided to open his own studio in Lahore, Izzat Majeed knew he wanted to build a large complex with good‑sized rehearsal rooms attached, but he initially deliberated over the best location. It was actually the musicians who explained that Sachal Studios would have to be in central Lahore. "I wanted to build it outside of Lahore because I wanted sedate and quiet,” explains Izzat. "And these guys came to me and said, 'Do you expect us to come to the boondocks to work?' They wanted to be near all the 16 other studios, within a radius of a 10‑minute ride, just in case they were called in some day. That is the reason, they told me, and so we found this plot of land in the middle of a car market.”

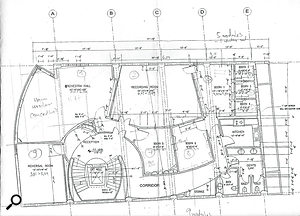

Sachal Studios, which is indeed (perhaps bizarrely) situated in the middle of a 'car and spare parts market', is a vast four‑storey complex. London‑based freelance recording engineer Christoph Bracher, who had already been working with both Izzat Majeed and his associate Jay Visvadeva for a number of years, was brought on board once the actual building itself had been constructed.  A floor plan of the Sachal Studios layout.

A floor plan of the Sachal Studios layout.

"Izzat asked me to come to Lahore and help him build his studio,” Christoph says. "The layout had already been cast in concrete and it was a completely new building he put up from scratch. It's substantially large, with maybe a 200‑ or 250‑square‑metre ground area. There's a large hall in the basement and a large rehearsal hall on the ground floor, then the first floor is the studio and the second floor is offices. It was a very nice project, a very grand project and the studios are almost like a smaller version of Abbey Road.”

Christoph's early tasks included designing the recording rooms and all of the interior acoustics. "Basically, I went out there when the concrete was cast and there was nothing in it,” explains Bracher. "And I just kind of sat down with the architect and the electrician and designed a basic blueprint for what was going to happen there. Then I used what acoustic materials they had available and what kind of wood was readily available. I basically tried to design it around what they could get hold of out there really, and what looked nice of course! Izzat is very much a visual man so everything he does has to look stunning. It's got a fantastic‑looking hardwood floor there and I have to say it is a spectacularly nice‑looking place. There's a large string room there where we under‑hung the ceiling and we put lots of wood cladding with Rockwool behind on the walls. It sounds quite lively and lovely now. It's become a nice room and it's got two smaller booths there, one of which I did with hard Rockwool. That's got quite a nice bright tone. That's usually where the percussion is recorded — I shouldn't say drums because, of course, they have the tabla and the dholak and that is the drums in that music. We also put a couple of RPG diffusers on the back wall in the control room.

"In general, I would say I kind of copied a studio in Southall I used to work at [Redfort Studios] because that was built for Indian music and it actually worked very well. The guy who owns it did some very good records there and I knew that place inside out so I copied some of his principles. I think I also stole some principles from an old BBC handbook on how to build a studio, actually.”

Christoph Bracher also specified all of the studio's recording equipment. "I would have spec'd a Pro Tools system if the main engineer there [Munir Kokab] had been computer‑savvy, but he was used to hard disk recorders so we put in two [Alesis] HD24 hard disk recorders,” says Christoph. "Then, Izzat really wanted a big Neve or SSL, but one of the big problems with that would have been power consumption. The AC system wouldn't have coped with a big analogue desk. Besides, I must admit, I grew up with digital as it came along and if you're recording in digital in the first place then you might as well stay in digital, in my opinion. So we bought a Yamaha DM2000 which just seemed a good compromise: lots of faders, enough buttons on it, a small enough footprint, small enough power consumption and we put lots of digital cards in it so it interfaces nicely with the recorders.”

Outboard gear installed at Sachal includes four Neve 8801s, four API 512C mic pres, two API 560 EQs, two API 525 compressors, an SPL Tube Vitalizer and an SPL de‑esser, Universal Audio LA2A and LA3A compressors, Eventide Eclipse and Lexicon 960LD effects units, a Rupert Neve Designs 5042 Portico tape emulator, an Antares AVP Vocal Producer, and Manley Labs' Variable Mu compressor and Massive Passive EQ. Meanwhile, the studio's mic collection includes two DPA 4011s, two Neumann U87s, a Neumann M249, a pair of Josephson C42s, four Shure SM57s and four SM58s, and the ubiquitous AKG C1000. Monitoring includes a pair of Genelec 1038Bs, a pair of Yamaha NS10s and three pairs of JBLs.