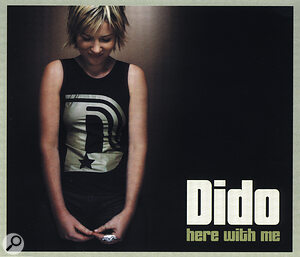

The standout track from Dido's debut album No Angel is known to millions as a TV theme, and is now a smash hit single in the UK. Sam Inglis talks to Pascal Gabriel, who co‑wrote 'Here With Me' with Dido and his colleague Paul Statham, and programmer James Sanger, who helped to shape the final version.

<!‑‑image‑>British artists have found it notoriously difficult to break the American charts in recent years, but singer Dido has succeeded in style. From press reports about this rise to stardom, it would be easy to think of her as a no‑budget singer‑songwriter who owes her success to a fortuitous piece of sampling by Eminem. While Marshall Mathers' use of 'Thank You' on his 'Stan' has certainly done her career no harm, however, Dido's story is hardly one of plucky, shoestring independent record‑making breaking through into the mass market. As a backing singer with her brother Rollo Armstrong's band Faithless, Dido has been involved in the music business for many years, and her American profile was built up through years of touring. Her slow‑burn debut album No Angel, top 10 in the US and now number one in the UK, showcases the talents of some very highly sought‑after writers and producers, and its development was personally supervised by the legendary head of A&R at Arista Records, Clive Davis. Record company clout also engineered high‑profile placements for 'Thank You' on the soundtrack to the film Sliding Doors, and for 'Here With Me' as theme to the American TV series Roswell High.

Here At Last

<!‑‑image‑>The first UK single to be released from Dido's album, 'Here With Me' perfectly illustrates the determination of both artist and record company to prepare the ground properly for her assault on the charts. It was mixed five times by three different production teams, having originally been recorded more than four years before its eventual single release in February 2001, and the finished version bears credits from industry names such as Rick Nowels, Ash Howes and string arranger Wil Malone. Three of those mixes — and the bulk of the recording and programming — were carried out by the co‑writers of 'Here With Me', Pascal Gabriel and Paul Statham.

Since leaving his native Belgium for London, Pascal has been a part of seminal dance outfits S Express and Bomb The Bass, before forming a writing and production partnership with Paul. The duo achieved chart success in America with singer Lisa Lamb, under the name Peach (see SOS August 1998). Pascal and Paul now work in Pascal's new studio, a converted dairy in Dalston, East London, but when their work on 'Here With Me' began in 1997, they were still working in a room in London's Strongroom complex.

Pascal explains how they became involved in working with Dido: "Paul and I were signed as writers to Warner‑Chappell, and Warner‑Chappell signed members of Faithless. We heard some of the demos she'd done and we thought the voice was great, but the music wasn't very good, so we did some new songs with her. The publisher really liked them, so they signed her for publishing, we did some more, and then she signed to her brother's label Cheeky in England, who then licensed her to Arista in the States. Clive Davis went mad over the tracks — he came to London and he had a big suite at a swanky hotel in London with a white piano and everything, and Dido had to come and play her songs acoustically to Clive. On the piano were two DATs, one of Whitney Houston's new album, and the other was Dido's demos. Cheeky had sent them 12 tracks, and the four or five that he'd chosen were all the ones she'd done with us. I was so chuffed, I was like 'Wow, someone can hear it!'

<!‑‑image‑>"'Here With Me' was the second song that we did together, in October 1996. We finished it on February 28th, 1997, at 5:17pm!" laughs Pascal, looking at the date and time attached to the file on his Apple Mac. "Then Rollo did a production of it, and they didn't think it was right, so they came back to us and said 'We want you to produce it more like the demo, because we like the demo more than any version we've heard so far.' The A&R guy gave us this cassette, because he was always referring to the version that he liked, which was 'the demo version'. I played him my demo version which was the one from my DAT here, and he said 'Oh, it's not that, it's faster.' It turned out that he had a cassette version that had been copied from the publisher from a second‑generation cassette, and it was compressed, it had dropouts in it, and it was faster, and there was no top, and that's the version the A&R guy knew. He liked the sound of this dodgy copy best, and so we set about recreating this.

"Paul and I did a version of it at the Strongroom, where we mixed it and everything, and they liked it but they thought it was too clean compared to the demo version, and they wanted it still more demo‑like. So then I did a mix that I recorded in my little programming room upstairs at the Strongroom, just on the Mackie desk, and they liked that loads better, but the balance of it wasn't quite right, and they wanted to mix it and finish it off somewhere else. I put it all onto RADAR, and then Dido then took it and finished off the production with Rick Nowels."

Starting To Write

Some of Pascal's many sound sources (from top): Sequential Pro One, Roland Juno 106 and Roland JD800 synths, Yamaha SY77 workstation, ARP Odyssey and Korg Mono/Poly synths.

Some of Pascal's many sound sources (from top): Sequential Pro One, Roland Juno 106 and Roland JD800 synths, Yamaha SY77 workstation, ARP Odyssey and Korg Mono/Poly synths.

<!‑‑image‑>Co‑writing with singers such as Dido now forms the bulk of Pascal and Paul's work, and their approach is always the same: "First we meet them and chat to see what makes them tick, and then you can go away and think about it in the bath for the next few weeks and mull it over. It wouldn't be so good if, say, she turned up today and I'd never met her before and we tried to start writing straight away. We've tried that and it's a bit cold. So we'd chat and play some music, and then when we actually start on the day, we decide what we're going to do — are we going to do something fast, something slow, a ballad? We usually come up with an idea each of what we want to do that day. With 'Here With Me', we'd talked about things like the big chords at the beginning of Twin Peaks, and we wanted something almost Icelandic, almost like Sigur Ros. We talked about it in very abstract terms: big, flat land, distant horizon, that kind of thing. Paul's the 'chords man' really, so he started with the chords in the verses, and slowly the thing took shape.

"Once you've got the basic sketch of the song, it's a bit like a body — once you have the backbone of it you kind of flesh it out. You just sing any old lyric over it that has syllables that sound good, to crack the melody, to see how well the melody's going to sit, and then either the singer sits at the back and fills in the dots while we're fiddling with the music, or he or she goes away that evening and comes back the next morning with a finished set of lyrics. Usually we get involved with the lyrics, anyway. Certain lyrics sound better for whatever reason — it depends where the 'f' falls, or the 'v' falls, or the 's' falls, all these little things make a difference. Coming from Belgium, I never really attach much importance to what lyrics mean, it's more what they sound like. I think in modern pop you can make it mean something by just tying good phrases together and then finding a good key word for the chorus.

"We'll do a day getting the shape of the music and the basic backbone of the song sorted out, and then another day to actually record and finish the vocals and finish the rough mix. Sometimes we spend a third day to really polish it, and that's about it, really. We do about a song a week. Some people have got these pop factories where they do a song a day, I couldn't do that. I might as well be a plumber. You've got to craft it.

"I think it's important when you write to get the structure right. This is quite a slow song at 80bpm, so we had trouble with the timing — by the time it gets to the end it's over four minutes, so we chopped out the string section that we had on the original version to move the last chorus forward by 20 seconds. Originally we had an intro on it, but then we just thought 'F••k the intro', so it just starts with a few chords, and then she sings. You save 20 seconds, and it's important, because radio programmers don't have time to waste.

"One thing I like much better about writing than producing is that you can work with all that stuff right from day one. When I used to produce a lot, you couldn't rewrite the song for the artist you were working with. I wished sometimes that you could, but you can't, that's their thing — if they want a 32‑bar intro, there's only so much you can do."

The First Version

Pascal's new studio in Dalston: "This used to be a milking dairy. You can see the marks on the floor where they used to hose the floor down for the cows. The cows used to hang out in the yard, and the other room was a hayloft. I kept all the character of it, that's why the whole floor is slanted."

Pascal's new studio in Dalston: "This used to be a milking dairy. You can see the marks on the floor where they used to hose the floor down for the cows. The cows used to hang out in the yard, and the other room was a hayloft. I kept all the character of it, that's why the whole floor is slanted."

<!‑‑image‑>The original demo version which Clive Davis liked so much, and which later mixes sought to reproduce, began with the chords played by Paul Statham, and an old sampled drum loop: "I remember the original drum loop was very noisy, but it was really vibey," explains Pascal. "We had a 'boom' bass drum from the second verse onwards, and then it stopped for the choruses. We made the choruses much lighter than the verses, actually: the verses are meant to be dark and really claustrophobic and hard, and then it goes into the chorus and suddenly it's all light and happy and open. Well, happier... We had a 'kick bass' doing the bass line on the verses, that's basically a TR808 bass drum, time‑stretched so you get a long sustained bass note. It's kind of a jungle‑style bass sound. We call that a kick bass because it's originally a kick drum — it still has the attack of an 808.

"We couldn't get the kick bass to reach the right pitch in the choruses, and it was a bit too heavy, so we simulated the kick‑bass sound in the choruses on the Studio Electronics SE1. The verses consisted of a big pad sound on the Korg Wavestation AV I used to have, an 'analogue pad' on the Yamaha SY77, and a soft sweep on the verses and on the intro of the second verse on the Roland MKS80, which was rising up behind the pads to give it a bit of movement, really. On the verses, halfway through the verses we had a more aggressive string sound from the Sequential Prophet VS rackmount, which is very mid‑'80s, a very hard, analogue string sound. The Novation DrumStation was doing basic backbeat stuff against the loop, just snare and bass drum. It was just a 909 setup on the DrumStation, nothing too complicated. The drum loop sounds were so complex and busy‑sounding already that we couldn't really do any more. We had no crash cymbals on it.

"Then we had big posh string samples on the chorus and in the bridge, and a Rhodes sound from the Emu Vintage Keys. And we had the Korg Mono/Poly going all the way through; it was a silly little sequence, but gave it a bit of movement all the way through the track, this slight, irritating rhythm very quietly behind it, and it worked. You had to know it was there to notice it, but it's worth it.

<!‑‑image‑>"We had a little bit of guitar that Paul did, which I think was kept on the final version, just to give it a bit of colour at the end. On the demo version we also had a double chorus at the end, and a string melody that we never used in the end."

The Final Version

The Logic Arrange window for Pascal and Paul's original demo version of 'Here With Me', including the short string melody before the last chorus, which was later removed. The audio tracks towards the bottom of the window include the comped lead vocal, the harmony vocals, a sequence on the Korg Mono/Poly and some snatches of electric guitar. Many of the synth parts survived into the final version, notably the electric piano riff on the Emu Vintage Keys that the song breaks down to in its quieter stages. The vocals were also kept, whereas the string parts were later replaced by a real string section.

The Logic Arrange window for Pascal and Paul's original demo version of 'Here With Me', including the short string melody before the last chorus, which was later removed. The audio tracks towards the bottom of the window include the comped lead vocal, the harmony vocals, a sequence on the Korg Mono/Poly and some snatches of electric guitar. Many of the synth parts survived into the final version, notably the electric piano riff on the Emu Vintage Keys that the song breaks down to in its quieter stages. The vocals were also kept, whereas the string parts were later replaced by a real string section.

<!‑‑image‑>When Pascal and Paul handed their recording of 'Here With Me' over to Dido and Rick Nowels, most of the major elements were present, including the vocal, drum pattern, bass sound and line, the electric piano riff that appears in the breakdown, and many of the other synth sounds. Rollo Armstrong's work on the track had also left its mark: he had chosen to replace programmed string parts with a live string section, recorded at London's Swanyard Studios with engineer Goetz. The string parts were composed by London's first‑call string arranger Wil Malone, best known for his influential work on Massive Attack's 'Unfinished Sympathy', and the section was led by top session violinist Gavin Wright.

For the final version, Nowels and Dido took the multitrack back to Swanyard, where they recorded a prominent looped acoustic guitar and some extra keyboard parts with engineer Ash Howes, who also presided over the final mix there. Nowels' keyboard sounds were set up by programmer James Sanger, who was also responsible for other significant alterations and additions to the song's palette of sounds. "I worked on three songs on the album," explains James. 'Here With Me' was already quite close to being finished, whereas I had a bit more of an involvement with the other ones. I spent 10 days working on that one song, though, so it was more than just putting a bit of extra tiddly‑tiddly stuff on it. A lot of what was used was already there in Pascal's version — there's no point changing something if it fits, obviously — but often Rick would want to try something again, so he'd play the bass again or something, and then decide that actually the original bass was good.

"A lot of what I did was work on the drums — all the drums were redone in our version. I didn't change the kick or snare pattern at all, but I added new sounds. It's the sort of thing Ash and I would normally do, so that when you turn it up there isn't just one puny thing going 'plip!', there's about 10 things going 'Raaa!' I do my drums using Ensoniq ASR10s — I've got a few of those — and SampleCell, which is a fantastic tool. The main brushed snare in the chorus is from an ASR brush kit.

"We did a Chamberlin string part, and Rick played all the pads. There was also lots of Pro Tools‑ing that went on. I had a real field day with the vocal effects. There are some reversed vocals, and I have a trick where I sample the reverb, and I get that looping and fading in as you go into different sections of the song. I use a phaser and a delay, and I'll sample a bit of vocal, and I'll modulate the start point of the sample to velocity, so if you hit the keyboard harder, the sample will start playing later into the sample. You can get a really nice juddery effect, and if you've got phase and delay on it, you can get a really nice trippy, swirly, phasey sound.

"I have a very particular way of using a certain set of things that creates a sound that I do. I've got a big Pro Tools system using Logic, but I use a lot of synthesizers as effects, and have things going out of Pro Tools, into the real world, through something and then back into Pro Tools. I've got a Gleeman Pentaphonic synth, one of very few made with clear perspex, and I use that to get very psychedelic sounds. It has an extremely trippy, glassy sound to it. If you ever hear one, you'll recognise it. I use it a lot for pads and arpeggios, but it's not MIDI, so you have to play it. I've also got a Moog Minimoog and an EMS VCS3, and I do things with a Lexicon Jam Man. I've got three of those, and every part that I do tends to have at least some part of it involved with a Jam Man somewhere.

"It was a big mix: there were more than 48 tracks, so a lot of stuff was in but not very loud. At the time the mix went down, there were at least 150 tracks in my computer, although lots of those were takes that hadn't been comped, because the way Rick works is that he'll carry on doing takes and takes and takes, and won't get around to comping them, so they have to stay in the computer in case he wants to hear something he did a week ago."

Christmas Present

James Sanger narrowly escapes being crushed to death by some of his vintage synths! The extremely rare, clear perspex Gleeman Pentaphonic is visible at the front.

James Sanger narrowly escapes being crushed to death by some of his vintage synths! The extremely rare, clear perspex Gleeman Pentaphonic is visible at the front.

By the time the finished version of 'Here With Me' was committed to Dido's album, at least 10 people had been involved with the production, programming and recording at some stage. Their efforts have, however, paid off in spectacular fashion. Not only is Dido's album a fixture in the top 10 on both sides of the Atlantic, but 'Here With Me' — surprisingly, her debut UK single — has been a massive airplay hit prior to its UK release. Unusually, it's found its way onto playlists at both Radio One and Radio Two, and with the additional boost of blanket coverage on both MTV and independent radio, was always destined for an equally impressive impact on the sales chart. It duly went straight in to the British hit parade at number four.

"I was away for Christmas and came back and suddenly it was like 'Oh, you've got a top 10 album, and a really big single coming out that's being played to death on BBC Radio 1'," laughs Pascal. Perhaps if we all write to Santa Claus next year...

Recording Dido's Vocals

Rick Nowels, who finished off the production of 'Here With Me', in his Los Angeles studio.

Rick Nowels, who finished off the production of 'Here With Me', in his Los Angeles studio.The most important part of the original recording of 'Here With Me', which survived unchanged through all the remixes, was Dido's vocal. She recorded both the lead and backing vocals with Pascal and Paul in their Strongroom suite.

"How I recorded the vocals on this track, and how I always record the vocals, is to record lots of takes all the way through, and get a singer routined to the song, and never concentrate on a particular bit, just sing over and over again and keep every take," explains Pascal. "You end up with maybe 12 or 14 tracks to comp, but you find some really good bits even from the tracks that you thought weren't going to be very good ones to comp from. The bits that most people remember, the little quirky bits, you'll find from a take where she didn't really feel she was confident with the song, but she let rip a bit by accident, and those bits sometimes are worth their weight in gold. It takes a long time — out of a two‑day writing session, we probably spent about three or four hours just comping. The first chorus consists of loads of different bits of takes, but it's cool. If you solo them, they sound like they're from different takes, but they work very well. It's really important, because if you're doing pop music with a singer, the singer is the most important thing. If you've got crap vocals, you can have the best backing track in the world, but it's not going to work.

"I never double‑track lead vocals. I think it's wrong to double‑track lead vocals. You can have backing vocals, of course, and harmonies — I'm not opposed to that at all — but on an emotional basis, I think you need to have just the one vocalist singing to you. If you have two vocalists singing to you, it sounds a bit odd. It kind of irons out the idiosyncrasies of each vocal if you have them tightly double‑tracked, I don't like that effect at all. I'd much rather have one really cool vocal and work at doing the vocal that you really want, than to try to do a quick vocal and think that if you double‑track everything it's going to be all right, because it's not going to be all right.

"We had no harmonies on the first chorus: the harmonies come in on the second chorus, and then there's an extra high harmony on the last chorus.

"All the vocals were done on my old Neumann mic. I just use the Neumann, which is a valve mic, going straight into a little Neve two‑input preamp, and then it goes into my Esoteric Audio Research compressor, and then straight into Pro Tools, it doesn't go anywhere near the Mackie desk, so it's a much cleaner path, and it's just great. It's quite a noisy mic, but valve mics usually are, and it's vibey, really cool. It works really well with good singers like Dido, because they belt it out and you get the warm valve compression feeling that you don't get from a normal mic."

Although there's plenty of space, Pascal hasn't bothered to build a vocal booth in his own studio: "I used to have a vocal booth when I worked upstairs at the Strongroom, and I never used it at all. And it's nicer because we can just chat, and it's really informal, and they relax, and it's not like 'Oh, I'm in a vocal booth and he's looking at me through the glass.' Often the main problem I find with singers in terms of nervousness is when they can't hear what's happening in the control room. They always think people are talking about them! Whereas if they're in the same room as you, it's not a big deal, and psychologically, it's much less of a problem."