The Digidesign connection

Phil Dudderidge cites the relationship Focusrite formed with Digidesign as “transformative” in the fortunes of the business: “I first met Dave Froker from Digidesign at AES in San Francisco in 1994, and that was to be the start of a ten-year-plus relationship that was very beneficial to both companies. Focusrite had got out of making consoles and were concentrating on outboard, and Digidesign were seeking to reach out to the entry-level market with Pro Tools, which until that point had only been a very high-end professional solution. Dave Froker recognised that getting a ‘lite’ version into the hands of musicians at the beginning of their recording careers could feed into sales of the professional product at a later point.

“He came to us initially with the idea of making software plug-in versions of some of our hardware. I said ‘great idea…but we don’t know how to do that. Why don’t you develop the plugins, and we’ll work on making sure that they sound like the analogue products (Red 2 and Red 3) that they emulate’? Probably our greatest contribution to the plugins in the end was their GUI — Richard Salter (Technical Director at that time) had the great idea, which seems so obvious now, to make the plug-ins' GUIs look like the Red Range hardware that they were emulating. As far as I’m aware, those plugins were the first to do that. The D2 and D3 plug-ins also brought some colour to Pro Tools palette that was very much shades of grey at the time, just as our Red Range hardware had brought colour to racks of analogue outboard.”

It seems so obvious now, to make the plug-ins' GUIs look like the Red Range hardware that they were emulating.

The plug-ins were to be just the beginning, however. The real turning point for the business arose with Focusrite’s collaboration with Digidesign on the MBox: a compact, affordable, audio interface for Pro Tools. “We developed it for them from Rob Jenkins’ original concept”, says Dudderidge. “It was jointly branded and they sold it through their sales channels from 2001 to 2005, bundled with a lite-version of Pro Tools. We were receiving royalties for it, rather than selling it ourselves, and that proved extremely profitable. Sales volumes were much larger than initially anticipated by either party — Digidesign told us they expected to sell 1,000 a month and by the end of our relationship they were selling about 6,000 a month —and that helped us build our balance sheet and pay off debts to the bank, debts to myself and really strengthen the company.”

The MBox entry-level interface for Pro Tools was “transformative in the fortunes of the business".By 2005, however, Focusrite and Digidesign had started to go in separate directions. Avid (Digidesign) had bought M‑Audio and discontinued any further developments with Focusrite, releasing a second-generation MBox, developed in conjunction with their new acquisition partner.

The MBox entry-level interface for Pro Tools was “transformative in the fortunes of the business".By 2005, however, Focusrite and Digidesign had started to go in separate directions. Avid (Digidesign) had bought M‑Audio and discontinued any further developments with Focusrite, releasing a second-generation MBox, developed in conjunction with their new acquisition partner.

“Things could have ‘fallen off a cliff’ for us once the second generation of MBoxes took over”, says Dudderidge, “but by that time we had started to ship our first Firewire interface range, Saffire. Rob Jenkins, who had worked for us installing consoles in the early years and was now our Technical Director, felt we needed to be in the interface business on our own account and having headed up the development of the MBox, he started the development of our first interface, so we were somewhat ready when our MBox revenue came to an end. We went with Firewire because it was perceived as offering better quality than USB1, but at the time we were locked out of Pro Tools which was only opened up to third party interfaces in October 2011.

By this time, computer manufacturers were driving the agenda for manufacturers of related products, as connectivity protocols moved quite rapidly from USB 1, to Firewire then to USB2, once the audio standard was established. Dudderidge takes a pragmatic view: “adopting new interface standards like Thunderbolt can offer great opportunity for improvement in the performance of our product. Change is just something we have to manage, in terms of maintaining products after they cease to be sold, to give as much longevity as possible. We’ll always keep stuff running as long as we reasonably can, but the time comes eventually when it is just not economically viable to continue to support a product. You could look at it as the price of progress —if you want to run the latest software you usually have to run it on more powerful hardware, so there is an inevitable pressure on musicians to buy new computers. Those of us who grew up in the analogue world tended to think that once you’d bought something it would run forever. But nothing lasts forever in the digital world. When we were doing our Firewire interfaces, we thought we’d never do another USB interface, and then USB 2 came along and that of course has been hugely successful, while Firewire audio ceased to be supported by Apple in 2016. Connectivity may drive innovation — Thunderbolt being a case in point — but Thunderbolt hasn’t been the commercial success that everyone thought it would be because for a lot of people USB 2 is good enough, so why would you pay the premium for something better? So now we’ve got Clarett interfaces with Thunderbolt for those who value the benefits, and Claretts with USB 2 at a slightly lower price point. A third generation of our globally-dominant Scarlett interfaces has just been announced, employing USB 2 via a USB C connection, with lots of other improvements too!”

Novation: “A sensible adjacency”

Focusrite’s improved financial position during the ‘MBox years’ allowed them to look at expanding through acquisition, and in 2004 their near neighbour Novation was bought out of insolvency. “We’d actually approached them a year earlier”, says Dudderidge, “thinking (a) they were local, (b) they were doing things we felt were adjacent to things we were doing. We were thinking at that stage not just about audio interfaces but about what we might do beyond studio outboard, and what they were doing with synthesizers and controller keyboards looked like a sensible adjacency. We found the company was not in great shape, but it took about another year before they accepted that was the case.

“It was an innovative business: Chris Huggett has always been a great synth designer and, partnered up with Ian Jannaway, they did a great job with limited financial resources, but they were always living somewhat hand-to-mouth. There’s no shame in that — I can remember plenty of times at Soundcraft when we were in that situation. It is a problem that innovative businesses often have unless they can find ‘angel finance’ or growth capital of some sort. We were in a position to put some real investment into the Novation business, building the brand and the brand values, getting good global distribution, and then partnering with Ableton when we created the Launchpad range of products, which has been a notable part of the success of Novation.”

The Launchpad range has been a huge success for Novation.

The Launchpad range has been a huge success for Novation.

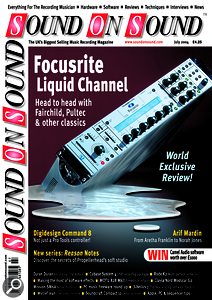

Focusrite's Liquid Channel innovative convolution-based processor: "I think everyone who wanted one bought one".2004 also saw Focusrite surprise the market with an innovative digital/analogue hybrid product in the form of their Liquid Channel — a high-end voice channel that had the ability to emulate a number of different preamplifiers and compressors using a new core technology called Dynamic Convolution, licensed from its inventors Sintefex. Liquid Channel was to win the accolade of Best Microphone Preamp in the 2012 SOS Awards, voted by the readers of Sound On Sound. Liquid Mix, a more affordable application of the technology, was spun off a year or so later. “They were very successful products for a period of time” says Dudderidge, “but I think everyone who wanted one bought one, and once we saw the sales falling off, we had to make a decision again.”

Focusrite's Liquid Channel innovative convolution-based processor: "I think everyone who wanted one bought one".2004 also saw Focusrite surprise the market with an innovative digital/analogue hybrid product in the form of their Liquid Channel — a high-end voice channel that had the ability to emulate a number of different preamplifiers and compressors using a new core technology called Dynamic Convolution, licensed from its inventors Sintefex. Liquid Channel was to win the accolade of Best Microphone Preamp in the 2012 SOS Awards, voted by the readers of Sound On Sound. Liquid Mix, a more affordable application of the technology, was spun off a year or so later. “They were very successful products for a period of time” says Dudderidge, “but I think everyone who wanted one bought one, and once we saw the sales falling off, we had to make a decision again.”

Crisis? What crisis?

When the financial crash of 2008 hit, causing a widespread recession whose effects are still being felt by some UK businesses today, Focusrite was in a better shape than many to survive it. In fact, they were to do a great deal better than just survive it. “In September 2008 we had a growth-oriented budget for 2008/9 and everyone was saying ‘what’s going to happen?’ because the banks were melting down” Dudderidge recalls his response: “I told everyone that unless we were absolutely forced to change by circumstances, we were going to stick to our plan. We had a very up-to-the minute product range, with the first generation of Saffires now replaced by the second-gen design, and we had no debt. That year, 2008/9, we didn’t grow, but we didn’t decline either, and from there on, it has been all steady growth.

“We set up a direct sales office in Germany to service the German retailers in 2009 and then our US office a year later. At that time, we were disappointed with our sales volume in the USA so we came to an agreement with our distributor to divide the role. They still distribute the products and bill the retailers, but our Focusrite Novation Inc subsidiary manages marketing and relationships with the primary resellers, as well as providing customer support for the Americas. A lot of marketing these days is channel marketing where we partner with the retailer in their marketing activities, on-line or otherwise, and that’s something we can do much more effectively ourselves locally rather than delegating it to a third party. That relationship with our distributor has worked extremely well — we’ve grown from selling about $5 million a year when we made the change in 2010 to about ten times that today.