Phil Dudderidge Executive Chairman of Focusrite plc.

Phil Dudderidge Executive Chairman of Focusrite plc.

Industry veteran Phil Dudderidge, now 70, may have plenty to look back on, but he’s still looking forward as Focusrite enters its 30th year.

“It’s a very good feeling when you wake up in the morning and you know why you want to go to work”, says Focusrite Executive Chairman Phil Dudderidge, with Focusrite plc having passed £75 million revenue last year and expected to rise further this year.

Focusrite is one of the great success stories of our industry, employing over 200 people at various locations around the world at the time of this interview, and occupying a commanding position in a number of different market sectors. Dudderidge, now 70, has steered the 30-year old business through all of its pivotal moments: picking up the pieces from one of Rupert Neve’s last forays into the large-format console market in 1989; re-inventing the company’s activities a number of times along the way in line with market trends; through to today’s, highly profitable, publicly-quoted plc on the London Alternative Investment Market (AIM).

It’s a very good feeling when you wake up in the morning and you know why you want to go to work.

“The benefits of flotation don’t come without effort,” says Dudderidge, “for our CEO and CFO in particular, as they have to represent the company to the investors on a regular basis, but taking the company public was something of a secret ambition of mine for a lot of reasons, some of them personal, some of them very much employee-focused. At the time that we floated, I’d been building up the company over a period of 25 years, I was approaching my 65th birthday, and felt I needed to do some succession planning. We had an existing share-option scheme in place for our employees in anticipation that there might be either a sale of the company or a flotation at some point in the future, and we revisited that because I wanted to make sure that everybody in the company had share options and would benefit from the flotation. And I mean everyone— they are all part of the team. It’s benefitted a lot of our people since the flotation as their options have vested and they’ve been able to pay off mortgages or buy their first home, as well as in many cases retaining shares in the business. It makes me feel very proud that, as a company, we’ve been able to have the kind of success that has afforded them those sort of rewards.”

The lesser-known 'Red: Birthday Cake' model was short-lived...It’s certainly not solely the above that has led to Focusrite receiving ‘The Sunday Times, 100 Best Small Companies to Work For’ accolade, in 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015 and 2016, to set alongside their multiple Queen’s Awards for Enterprise Innovation accolades. Dudderidge has previously stated his intention of making Focusrite “the company I'd like to work for if I was an employee." The calm, creative atmosphere that pervades their High Wycombe, UK headquarters, however, lacks nothing of an undercurrent of competitiveness and a desire to make products that are not just good value, but ones that exceed expectation and enhance the user’s music-making experience. It doesn’t seem too much of a stretch to see some of that pervasive ethos emanating from the man at the top. A man who started his lengthy journey in the music business in the 1960s driving a van for UK bands like Fairport Convention and Soft Machine, who soon found himself running sound systems for Led Zeppelin on their Spring 1970 tour and, by 1973, making some of the world’s first dedicated live-sound mixing consoles under the Soundcraft brand, leading ultimately to the Focusrite we see today.

The lesser-known 'Red: Birthday Cake' model was short-lived...It’s certainly not solely the above that has led to Focusrite receiving ‘The Sunday Times, 100 Best Small Companies to Work For’ accolade, in 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015 and 2016, to set alongside their multiple Queen’s Awards for Enterprise Innovation accolades. Dudderidge has previously stated his intention of making Focusrite “the company I'd like to work for if I was an employee." The calm, creative atmosphere that pervades their High Wycombe, UK headquarters, however, lacks nothing of an undercurrent of competitiveness and a desire to make products that are not just good value, but ones that exceed expectation and enhance the user’s music-making experience. It doesn’t seem too much of a stretch to see some of that pervasive ethos emanating from the man at the top. A man who started his lengthy journey in the music business in the 1960s driving a van for UK bands like Fairport Convention and Soft Machine, who soon found himself running sound systems for Led Zeppelin on their Spring 1970 tour and, by 1973, making some of the world’s first dedicated live-sound mixing consoles under the Soundcraft brand, leading ultimately to the Focusrite we see today.

“If you’ve got an entrepreneurial heart beating in your chest, you’ll find something to apply it to,” he says. “Some of my early steps were accidental — you just find something that you can apply your ability to and think ‘I’ll do that’, but then you get a fork in the road and you choose which one to take, and that’s how careers develop. In those days there was a lot of opportunity — there was everything still to be invented! If I’d been born ten years later I wouldn’t have had the same opportunities, but I think I would have had different ones.”

“A great learning experience”

Phil Dudderidge describes the opportunity of running the sound for Led Zeppelin’s tour as “a great learning experience. I was learning every day: the first time I actually used a WEM Audiomaster (two of them, making 10 channels in all) was on the first gig I did with Led Zep”, but it was also an experience that convinced him that he didn’t want to spend his time on the road with bands. “We had just three crew to do an arena tour in the States. It doesn’t make any sense at all by modern standards! Driving everywhere, flying only when it would have been impossible to do otherwise… and there were only two legs where we had to fly. It was the responsibility of the promoter to provide the PA system at each venue, so they would hire locally and we would just show up to the gig with backline. I used the WEM PA that we carried with us ‘just in case’ as monitors. Nobody had monitors in those days, but I’d set up a WEM PA on either side of the arena stage for the benefit of the band.

“The gig we did at the Forum in LA was my first experience of a ‘flown system’, rigged up high in the venue — at every other gig the PA was sitting on the stage — and that John Meyer-designed system from McCune made a real impression on me. I came back to the UK and a year or so later, after a stint with Hiwatt, started a little company building PA systems under the RSD brand. Electronics designer Graham Blyth joined me at RSD, along with my original partner in RSD, Paul Dobson. We split from him after some argument or other, and Graham and I took the mixer part of the enterprise with us as the foundation of the console business that we called Soundcraft. I became very involved in running sales and marketing, and building an international distribution network for Soundcraft while Graham designed and oversaw production.. At a time when most people in this business were much more focused on just making equipment, I was developing my skills as a marketer. I think a lot of people didn’t quite appreciate the value and importance of a brand in those days.”

Over the course of the next 15 years, Soundcraft expanded from live-sound consoles into large-format recording mixers and then successfully rode the wave of the 1980s, pre-computer, home- and project-studio recording boom. When their US distributor, the giant Harman Corporation, moved in to buy the company in 1988, Phil Dudderidge admits he felt “something of a vacuum: for me, it really was ‘so what do I do next’?”

With substantial personal wealth and still under 40, he was thinking of taking a break from business: “I had decided I wasn’t going to do anything for a while — after 15 years running hard with Soundcraft, I thought I deserved a year off.”

“This opportunity arose…”

Phil Dudderidge never did get his year off. The late ‘80s were not a great time to be in the large-format recording console business and renowned console designer Rupert Neve’s Focusrite company had got into financial difficulties. Even the big names like Solid State Logic and Neve (Rupert’s former company) were struggling against both a financial recession and a background of a changing music business that was seeing the closure of many of the larger professional recording studios. The company had gone into insolvency, but Dudderidge nevertheless saw an opportunity and was able to buy the assets — the brand, the designs, etc —and restart the business. “One of the reasons why I felt able to acquire Focusrite was the fact that the production was in the hands of other companies, so it would be relatively easy to start the manufacturing process of at least the outboard straight away. At Soundcraft we’d had a factory with about 300 people and that was something that I was keen not to repeat.

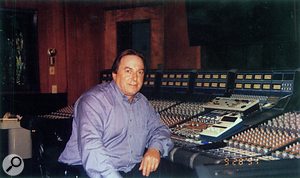

Phil Dudderidge seated at a Focusrite console in 1994.

Phil Dudderidge seated at a Focusrite console in 1994.

“Another factor in my decision was that I had somebody else in [former record producer and console designer] John Strudwick, who was prepared to ‘get his feet wet’ with it. He was intended to run it and I was just supposed to ‘hover above it’, provide the working capital and make sure it was going in the right direction. And so it did for the couple of years before I had to take over the reins. Rupert already had the module-sales business going and that gave us cashflow from the start. That was the ISA rack with vertical modules, like an oversized 500-series rack. There was quite a big market for those for a time — people with SSL studios wanting something that sounded a bit more like a Neve for tracking purposes.

“The consoles were a different matter. The final assembly of those, including the frames, was all done in-house by the company when it was in Rupert’s hands, but by the time we acquired the assets, all the people had gone and that original console had proved itself to be not reliably producible. There were only two of them built and they both had to be finished in the studios to which they had been sold — Electric Lady Studios in New York and Master Rock in London.

We decided to get out of the console business altogether and reinvent ourselves as an outboard company.

“We released 19-inch rack versions of the original ISA modules’ circuitry — derivatives of those products actually continue to sell in modest numbers to this day — and while they were providing our initial cashflow, we were able to concentrate on creating a new version of the console: the Focusrite Studio Console. With hindsight, that was really the wrong thing to be doing: our console prices were simply too high for studios at that time. The big companies were heavily discounting and we just couldn’t compete. Eventually we decided to get out of the console business altogether and reinvent ourselves as an outboard company. I think I had become a much more mature business person by then and was able to approach running Focusrite with rather less emotion and a bit more business savvy than might have been previously.The original Red Range introduced in 1993 — again, ISA circuitry, but repackaged in a more attractive way to reach a new audience — was the beginning of that strategy.”

Red 1 mic pre: the first in the range that changed the aesthetics of studio outboard.

Red 1 mic pre: the first in the range that changed the aesthetics of studio outboard.

The physical format — bright red, with a thick, curved-fronted extrusion that meant that it would sit proud of other units in a rack — was unusual for the time when most other rack gear was flat-fronted, in black, silver or grey. “It just appealed to our own aesthetic sensibilities” says Dudderidge, “and we thought it might appeal to others, too. It worked: people wanted to buy it before they even knew what it did! That design came from our Technical Director at the time Richard Salter and Barry Neale our draftsman, and is something that has been emulated by quite a few people since!

“We then added our Blue range — a mastering EQ and compressor with switched controls for precision and repeatability — but that’s a small market and it just wasn’t economically viable over an extended period, so we decided to stop it. That’s something we’ve always done at Focusrite: recognised when products ceased to have commercial viability and dropped them rather than try to keep everything in the catalogue.”

The ‘ADAT revolution’ of the ‘90s opened up the possibility for people to record digitally with relatively inexpensive equipment, creating a boom in hardware-based home studios that was to continue until the arrival of computer- based recording. Dudderidge saw an opportunity. “Lots of people with ADAT-based studios were looking for outboard equipment, but not at the sort of prices we were selling our Red range and ISA products, so we created our Green range as our first endeavour to bring down the cost of outboard mic preamps, compressors and combinations thereof. The Green range eventually consisted of five different products, with the channel strip in particular doing well for a few years.” However, the home-recording market was growing at rate greater than its ability to afford even the Green range, creating even more downward pressure on pricing. Focusrite responded with their Platinum range: “We managed to significantly cut the price again, offering similar functionality but at roughly half the cost of the Green range equivalents, achieved partly through volume and partly through design choices. We started out with those being made in Scotland, but eventually transferred manufacturing to China.”

Focusrite’s first venture into Chinese manufacturing was actually with the Control 24 — a control surface for Digidesign’s Pro Tools software — designed in the UK by Focusrite, but manufactured in China and sold by Digidesign. Having gained that experience they then started to move more of their manufacturing into the same Chinese manufacturer over the next two or three years. “How well Chinese manufacturing works really does depend who you partner with and how closely you work with them” Dudderidge says, “but for us it worked better than working with UK sub-contractors. We’ve never had our own factory.”