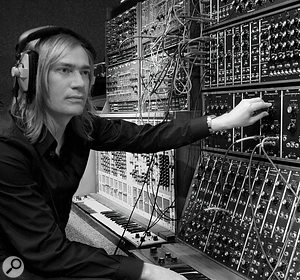

Benge: Synth History In Action

Benge's Twenty Systems is more than just an album. It's also a book, and a historical document, and quite possibly a buyer's guide to vintage synths. Each of the 20 tracks was created using only one synth, working along a timeline from the 1968 Moog modular to 1987's Kawai K5m additive synth.

"I've been collecting up old synths since the early '90s," says Benge, aka Ben Edwards. "I had the idea of making a record where I limited myself to one instrument per track, because I liked the idea of simplifying the way I worked. I made a few tracks that I liked but which ended up on a shelf and were not really part of an album or anything. Then one day I was sitting in the studio working on the EMS VCS3 when it occurred to me that I had at least one synth from each year from the late '60s to the late '80s, and I thought it would be possible to do a track on each one and then put them in chronological order.

"It was quite difficult to arrange and work out the chronology of the synths I had used, as there is sometimes conflicting evidence about when they were released. I did have to make a few compromises. For example, I used 1974 for the Oberheim Four‑Voice which didn't come out until 1975, but it uses SEM modules from 1974. Also, I used the Yamaha CX5M from 1985 instead of the DX7 to represent FM synthesis, because the Fairlight CMI 2X also came out in 1983, which I wanted on the album.

"Some years were more prolific than others in terms of great or groundbreaking instruments, and if I had to make a choice between more than one instrument in a certain year I would try and use one that was typical of its time, or which helped to map out the general technical development of the synthesizer. For example, the 1973 Roland SH2000 could not really be described as a classic in the same way as as the Minimoog that came out a few years earlier, but I did feel it was important to include it, as it was one of the first synths to have completely preset sounds, and it brought those sounds to a whole generation of musicians because it was so affordable."

The music on Twenty Systems is a balancing act between the twin goals of creating something musically satisfying and allowing the individual character of each instrument to reveal itself as clearly as possible. "I wanted to hear the sound of each instrument and try and let it dictate how each track evolved. On top of that, I let the chronology of the year each instrument was produced dictate the arrangement of the record. Many of the systems have on‑board sequencers or arpeggiators, which help to emphasise the idea that the machines can run by themselves, and I used them where possible to automate the playing process. However, it is not the same as having automated compositional tools, which is a very interesting field that I would like to explore in the future.

"What makes the synthesizer so unique is the concept of voltage control, and later digital control, as it replaces the need for direct physical interaction with the instrument. With other instruments, you have a distinct reference to the physical actions of the player. You can almost see them sitting at their instrument while you listen. Even though some keyboards like the CS80 have great interactive capabilities, I still like the abstract nature of synthesizers, because they allow the possibility of having no gestural reference or performer virtuosity, which for me can get in the way of the listening experience (and is a great excuse for not practicing my keyboard scales!). For example, on the CS80 you can use polyphonic aftertouch to control parameters that would not be possible on an acoustic instrument (which would normally only be volume and timbre brightness). You could have it control LFO speed, or oscillator pitch, or pretty much anything, and at that point it becomes difficult to connect the gesture with the sound it produces."

The album, with its lavish packaging incorporating a beautifully illustrated book to accompany the music, is clearly a labour of love, inspired by the 15 years Ben has spent collecting vintage synths.

"I have always loved buying yesterday's forgotten cast‑offs, some of which are beautifully made, as well as being mechanical and technological masterpieces. A few of these instruments are very desirable again, but I got some of mine for next to nothing; some were even given away rather than being thrown out.

"For me, the period between 1968 and 1988 is the most interesting, because before the late '60s synthesizers were not really defined as a distinct instrument. You had electric organs and a few other keyboard instruments like the Philicorda and Mellotron, but really the synthesizer started with Bob Moog's modular systems and also those produced by Don Buchla, after the introduction of voltage control. These were followed in the early '70s by simpler and more compact systems in the form of the various monosynths brought out by manufacturers all over the world. Then, as technology moved on, polyphonic synths emerged, followed in the '80s by fully digital and computer‑based systems, of which the Synclavier was the ultimate example. Analogue synthesis eventually died out. After the late '80s I feel that synthesis entered a new phase of evolution with the advent of powerful PCs and affordable workstation keyboards. Not that I don't like the idea of computer‑based music production, or 'Jack of all trades' instruments, I just felt that there was a natural break in the development of the synthesizer at that point.

"It's interesting to see the current resurgence of analogue synthesizers, be it real or virtual, because it shows that people were obviously missing something during the '80s and '90s. Things seem to have gone full circle, as there are now more manufacturers of modular analogue equipment than ever before. It's not just the sound of large analogue systems that is so desirable, it's also the way you physically interact with them, not necessarily in a gestural way, but in the same way that people have moved away from mixing complete tracks inside the computer using a mouse. It would be great to see someone manufacture a 'mega‑synth' along the lines of the Fairlight or Synclavier that had the functionality of one of the new native computer-based systems but with a dedicated physical interface. But I suppose I would have to wait 20 years until it became obsolete before I could afford to buy it — maybe for the follow‑up album!"

Benge's Twenty Systems is out now on Expanding Records.

Jacopo Carreras: Making Software To Make Music With

Jacopo Carreras' album, From Bed To Couch, is not your average piece of Berlin techno. In fact, it touches on so many musical styles that it'd be a brave reviewer who attempted to classify it at all. Its eclectic sound is the outcome of an equally unusual production process, which saw Carreras shun commercially available DAWs and plug‑ins in favour of his own software.

"I do not find commercially available software limiting," insists Carreras, "I simply did not find a mass‑produced product which satisfies all of my personal needs. Some cars have good mechanics, others good electronics, but in the end what you want, if you find a way of building it, turns out to be best for you.

"I built some patches that allowed me to do certain things, maybe not super-original pieces of technology, but for sure very individual pieces of gear to play around with.

"I think music is getting a new dimension, a dimension that opens to spaces not explored before: this dimension is what used to lie behind the music, and now can be music itself. Nevertheless, I used [Ableton] Live for the first time during the album, controlled via MIDI events by a Max patch. So I used commercial software, but in my own way.

"I work with an external VA [virtual analogue] synth, a drum machine, and of course my bass, sometimes a guitar, but mainly as sound generators. It really depends on what is going on. What I cannot really find replicable in a software environment is a mixing desk. Maybe I am old‑school in this, but a true feel of a fader, or potentiometer, well, it's always good. When I was a teen, and I saw a real big console for the first time, that was inspiring — all those pots! So when I became an adult I searched for quite a while for a mixer, a Mackie 24:8 — maybe not the best, but a really important mixer for me. When I could afford it, second‑hand of course, I got it, and when I use it I have a feeling of satisfaction I cannot really put into words. It's what allows me to make the interaction man/machine, by sending audio input data, feeding it back to the computer, or to the [Access] Virus's vocoder, for example."

Some of Carreras' own plug‑in designs are even included on the CD, so buyers can try them out for themselves.

"The plug‑ins are not there to say I am cool, or because I want to make money from them — it makes me laugh even thinking of it. They are not perfect, the graphics are clearly minimal by choice, but they work, and do what you ask them! They are part of the music, a music with which you can interact. More and more I have the feeling that music will also be delivered to listeners as a 'generative package', or something we can interact with. I do not say that traditional ways of listening to music will disappear, not absolutely. But this dimension of interaction, this is what I am after, since this is how I make music, interacting with machines, but also listening to what is going on around me, and playing in front of an audience.

"The plug‑ins are divided into two sections, the ones that deal with processing an incoming signal, and the ones that deal with processing control data. The first section is a collection of signal processors, of which I like the sound or I can control well.

"The second section has a general programming approach, which then specifically deals with audio loops or MIDI data. The approach is simple: I have a sequence of events, these events are related to pitch, dynamics, position, direction, duration and tempo. These events follow a rule that is determined by four parameters and the playback position of the sequence. You can store a certain number of presets, and play with them with a MIDI controller. In these presets you can store also the parameters which affect the rule mentioned above, and interpolate linearly between preset 1 and preset 32, with a percentage value.

"This approach is then applied to audio data, like in the Ugo plug‑in, or to MIDI, as in the Arpeggiator, which would then drive the hardware VA. The closest example is the simplistic version of raga music. Start, mix it up by following certain rules which define a framework within which things happen, then go back to the beginning. I find that the word 'sampling' is not enough any more: many musicians like me clone audio, which then becomes a living thing on its own, so they actually create a new shape from a clone. A clone can then walk with its own legs — in this case, with its own waves..."

From Bed To Couch, and its associated plug‑ins, are available now on Lan Muzic. Interviews by Sam Inglis.