In 10 short years, the iPad has changed the way we make and record music. We explore what the current line-up has to offer, and what the future might hold.

It seems almost inconceivable that a decade has passed since Apple unveiled the iPad in January 2010. Steve Jobs described it as the company's "most advanced technology in a magical and revolutionary device at an unbelievable price". And while many derided the use of the term "magical", looking back 10 years on, it really was. Here was a device retailing for just shy of £430$500 that provided transformative experiences for basic tasks like web browsing, whilst also laying the foundations for so much more thanks to the sophistication hidden behind a multi-touch-capable, 10-inch piece of glass.

At an Apple Special Event held just over a year later, Jobs declared that 2010 had been the "Year of the iPad", and it was certainly the year of the iPad for Apple. With over 15 million sold in the nine months the product had been available from April to December, the iPad brought in a respectable revenue of $9.5 billion and eclipsed every previous attempt at a 'Tablet PC' ever sold.

The iPad 2 was quite a step forward for a new product category introduced less than a year before. It was thinner and lighter than the original, naturally, but with better performance, more memory, front and rear cameras, and a gyroscope. Where Apple emphasised the original iPad as being suitable for productivity with iWork apps such as Pages, Numbers and Keynote, the release of GarageBand and iMovie alongside the iPad 2 showed that Apple also saw this device as being suitable for creativity.

Since then, the iPad has exploded, with new hardware and software appearing annually. And with hindsight, I'd posit that 2019 was perhaps the most significant year yet in the product's life. This was the first time all hardware variations introduced thus far — the iPad, Air, mini and Pro — were available simultaneously. And, in terms of software, 2019 was the year Apple made a clear distinction between the versions of iOS (the company's mobile operating system) for iPhones and iPads.

Meet The Family

The first member of the iPad family is the iPad itself. A seventh-generation model was quietly introduced in September 2019, representing an entry-level step into the ecosystem for £349$329. This latest iPad obviously exceeds what was possible a decade earlier, offering respectable functionality powered by an A10 Fusion chip and 3GB of memory (the previous model also had an A10 but with only 2GB of on-board RAM). This seventh-generation iPad enlarges the traditional 9.7-inch display to 10.2 inches, with an increased 2160 x 1620-pixel resolution. It's aesthetically akin to the iPad Air, with which shares the same 9.8 x 6.8-inch dimensions, whilst being almost unperceivably thicker and heavier by 0.05 inches and 27 grams.

The iPad represents tremendous value and is perfect for using apps to control another application. Such pairings include Logic Remote with Logic Pro X, Cubase iC Pro and Cubase, Avid Control with EUCON-compatible applications, and so on. The A10 is capable of running more than just controller apps, of course, although there's no escaping the fact this iPad is designed with a budget in mind. Trade-offs are especially noticeable when it comes to the screen, which lacks features such as True Tone and the visceral fit and finish of more expensive models; reflectivity is greater and the distance between the glass and the display seems more noticeable.

The more advanced iPad Air was first introduced in late 2013 as being "dramatically thinner, lighter and more powerful". However, after a second iteration was released a year later, in 2017 this iPad vanished into, well, thin air, only to be gently reintroduced last year. Like the new iPad, the third-generation iPad Air also has a larger screen, growing from 9.7 to 10.5 inches with a higher resolution of 2224 x 1668 pixels, but with a smaller surrounding bezel and maintaining a healthy depth and weight of just 0.24 inches and 456 grams. Based on the more powerful A12 Bionic (also with 3GB memory), the neoteric Air offers a perfect balance between performance, size and price. It's therefore the iPad most prospective users will likely choose if moths haven't raised families in your wallet.

Accompanying the discreet announcement of the new iPad Air was a fifth-generation iPad mini, for those who prefer a more Lilliputian size. The original mini was unveiled at a Special Event on October 23th 2012, having essentially the same specifications as the iPad 2 but with a 7.9-inch display. This new model has similar internals to the latest Air, however, featuring an A12 and 3GB of memory. With a 2048 x 1536 resolution in a 5.3 x 8 x 0.24-inch form factor weighing just 300g, it's certainly a cute companion.

The Biggest News Since iPad

The flagship member of the family is the iPad Pro, which was unveiled at an Event in September 2015 as "the biggest news in iPad since iPad", introducing new concepts, both technically and spiritually. Powered by the A9X processor and 4GB memory, the Pro was said to offer 22 and 360 times more CPU and GPU performance respectively than its original ancestor. And, from a sonic perspective, it was perhaps the point at which Apple started putting more resources into its audio hardware, with the Pro featuring a four-speaker array that could balance both left and right channels and high and low frequencies depending on how the device was held.

Physically, the Pro had the same stylings as the Air, but with a 12.9-inch display — the "biggest" display Apple had (and have) used in such a device. However, perhaps the 'biggest news' of all, which is why the Pro was also a spiritual leap, was its support for two new accessories: the Apple Pencil (see the 'Who Wants A Stylus' box), and the so-called Smart Keyboard. The latter was a keyboard cover not unlike Microsoft's Surface Type Cover, which magnetically attached to the Pro and provided power and data communication via a new three-dot Smart Connector. Today, all iPad models except the mini include a Smart Connector on the side or rear of the device.

While the iPad Pro was a great iPad, to be sure, this original model did feel slightly bulky in your hands. With a footprint of 8.69 x 12.04 x 0.27 inches, it weighed 713g and had a relatively large bezel accommodating a Home button with Touch ID. Apple seemingly responded to this observation with the introduction of a 9.7-inch iPad Pro six months later, which was apparently the company's most popular screen size in such a device. This smaller Pro looked like an iPad Air, but was powered by similar internals like an A9X, but with 2GB memory, adding technologies like True Tone.

Second-generation iPad Pros were shown at the 2017 Worldwide Developer's Conference, available in both the original 12.9-inch size and a new 10.5-inch model replacing the previous 9.7-inch incarnation. Based around an A10X and 4GB memory, these iPads introduced ProMotion, enabling a dynamic screen refresh rate that was scalable to 120Hz. This made interactions with the display smoother and more responsive, improving the latency of the Apple Pencil.

However, it wasn't until the release of the third-generation iPad Pro in October 2018 that the product hit its stride, redesigned with a minimal bezel, eschewing the Touch ID sensor in favour of Face ID. Aesthetically, Apple moved away from the chamfered appearance of other iPads, returning to the original iPad's straight edges with a design conveying a Bauhaus seriousness. Weighing 641 grams, the 8.46 x 11.04 x 0.23-inch dimensions of the 12.9-inch model displayed a 2732 x 2048 resolution, and felt more comfortable than its predecessor. I really liked this size, though some will prefer the 11-inch model, measuring 7.02 x 9.74 x 0.23 inches (with a smaller 2388 x 1668 resolution) and weighing 471g.

Upgraded with an A12X Bionic and at least 4GB memory in all models (more on this later), the audio system was further improved with woofer and tweeter pairs for the four-speaker output. Apple also dropped the Lightning connector in favour of a USB‑C port that could output power, enabling audio interfaces like RME's Babyface Pro to be used directly, or for charging other devices like, say, an iPhone. But it does mean — at least in the short term — you'll probably need to purchase USB‑C to Lightning adaptors and cables to use existing peripherals.

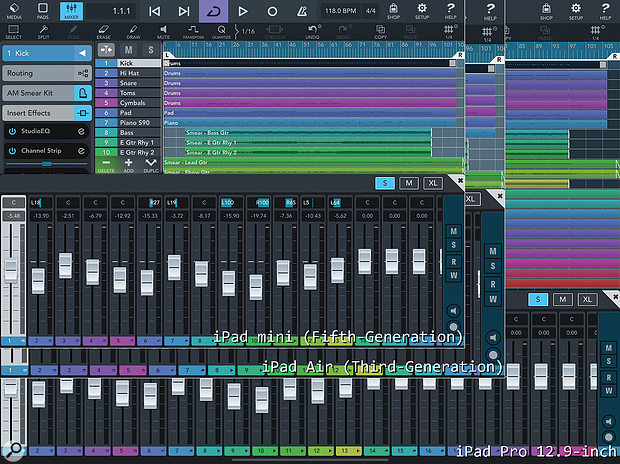

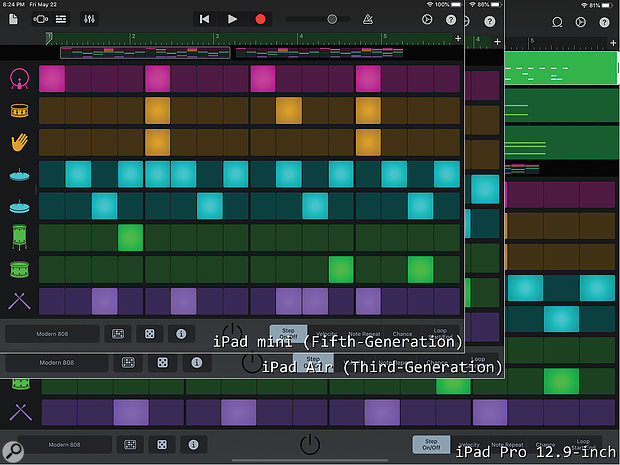

What a difference a display makes. Here you can see two approaches adopted by apps when handling the different display sizes offered by an iPad mini and the larger canvases of the iPad Air and iPad Pro 12.9-inch. While Cubasis scales the controls, as you might expect, GarageBand presents two distinct views, with the largest revealing part of the Tracks view alongside the step sequencer.

What a difference a display makes. Here you can see two approaches adopted by apps when handling the different display sizes offered by an iPad mini and the larger canvases of the iPad Air and iPad Pro 12.9-inch. While Cubasis scales the controls, as you might expect, GarageBand presents two distinct views, with the largest revealing part of the Tracks view alongside the step sequencer.

The A & Z Of The New iPad Pro

During 2019, then, Apple refreshed every member of the iPad family except for the Pro, which wasn't surprising given this had already received a significant redesign late-2018. But it therefore made sense for the Pro to be the first new iPad hardware of 2020, once again further blurring the lines between personal computing devices with the slogan: "your next computer is not a computer". OK, computer.

The fourth-generation model is powered by Apple's new A12Z Bionic chip, which, as the nomenclature suggests, doesn't offer the same significant silicon leap we've witnessed between previous generations. The Geekbench scores for the new iPad Pro 12.9-inch I had for review were 1128 and 4689 in the single and multi-core tests, whereas the previous model (according to Geekbench Browser) yielded average single and multi-core results of 1112 and 4579.

One reason for the similar results is that it's been speculated the A12Z builds on the same eight-core CPU design as the A12X, but with an additional, eighth GPU core for enhanced graphics performance. The difference this makes can be measured running Geekbench's Compute test, with the new Pro achieving a Metal score of 10100 compared to the 8848 average scored by the previous generation. (Metal is Apple's technology for low-level access to graphics hardware, both for visual and other computational tasks.)

Here you can see the relative single- and multi-core Geekbench scores between iPads, with a mid-range 2020 MacBook Air included for good measure.

Here you can see the relative single- and multi-core Geekbench scores between iPads, with a mid-range 2020 MacBook Air included for good measure. While not scientific, here are the percentage peak DSP loads as reported by Cubasis 3 playing back the Smear demo Project. To what extent Cubasis supports multiple cores is unknown.

While not scientific, here are the percentage peak DSP loads as reported by Cubasis 3 playing back the Smear demo Project. To what extent Cubasis supports multiple cores is unknown.

Benchmarks aside, there's an important change to the new iPad Pro's viscera that may have more impact. Even though Apple never discuss this specification, most 2018 models featured 4GB memory, except for configurations with 1TB storage that included an additional 2GB RAM. But with the 2020 refresh, all Pros now include 6GB — essential when you're running a profusion of music and audio apps simultaneously.

Otherwise, the specifications of the 2018 and 2020 iPad Pros are relatively similar. A second rear camera has been included for Ultra Wide shots, along with five microphones described by Apple as offering "studio quality". And while they do produce cleaner-sounding results than before (presumably using the array to handle noise cancellation), I think it's fair to say readers of this particular magazine will have a different expectation of what "studio quality" means in this context.

However, one final addition of noteworthy curiosity, and the reason I suspect the A12Z has an additional GPU core, is the inclusion of a LiDAR Scanner next to the rear cameras. A LiDAR essentially consists of a sensor that measures the backscattering of different wavelengths of light emitted, which basically means it's an extremely accurate way of scanning the depth of 3D targets. Apple says its LiDAR Scanner can measure the distance of a surrounding object within a five-metre range with nano-second latency and works indoors or outdoors (which isn't uncommon as LiDARs are often used by self-driving cars). Data from this sensor, in concert with the cameras and motion sensors, enables the new iPad Pro to propel Augmented Reality (AR) experiences to a new level.

I always thought my living room was missing a baby grand piano! Here you can see Piano 3D position a grand piano in a space and perform in situ — all I need now is a candelabra!

I always thought my living room was missing a baby grand piano! Here you can see Piano 3D position a grand piano in a space and perform in situ — all I need now is a candelabra! Apple have been pioneering AR for several years, leading to impressive support in both hardware and software. This could be seen as premature, given the lack of what one might describe as 'killer' apps. But without such momentum AR could become a chicken-and-egg problem, so the company are effectively providing the chickens with the expectation developers will supply the eggs. And, as Apple pointed out to me, the company's CEO, Tim Cook, has spoken effusively about this, remarking "I'm excited about AR. My view is it's the next big thing, and it will pervade our entire lives."

Apple have been pioneering AR for several years, leading to impressive support in both hardware and software. This could be seen as premature, given the lack of what one might describe as 'killer' apps. But without such momentum AR could become a chicken-and-egg problem, so the company are effectively providing the chickens with the expectation developers will supply the eggs. And, as Apple pointed out to me, the company's CEO, Tim Cook, has spoken effusively about this, remarking "I'm excited about AR. My view is it's the next big thing, and it will pervade our entire lives."

That's a bold statement, but something else Cook said resonated with me more specifically, having extra pertinence now viewed through the unavoidable lens of Covid‑19. "I think it's [AR] something that doesn't isolate people. We can use it to enhance our discussion, not substitute it for human connection." When you contemplate the broader implications, consider the human connection when musicians play together and how unhuman online collaboration currently feels. Don't get me wrong, such tools are useful and have improved immensely, but it's hard to escape the inherent social disconnection when working this way.

AR could facilitate a virtual studio in any room, giving you the ability to watch and interact with a virtual representation of a player for added communication, such as individualised talkback. Or imagine you're remotely monitoring a mixing session... Why not have a console, where you could adjust the controls to indicate (and irritate) your mix engineer with ideas? Current apps like Piano 3D (see pictures) demonstrate placing a virtual piano in your room, viewing the keys being played from any angle; or you can hover your iPad above a real piano keyboard, superimposing notes to be played as a teaching aid. And that's just scratching the now easily measurable surface!

Whether it's because you want a device for recording an idea in a mobile environment or studio, a device that can control your Pro Tools rig, or a device that becomes a tapestry for synths and effects, there are many moments where musicians and audio engineers will benefit from having an iPad.

Say Hello To iPadOS

Due to its heritage, the iPad launched running an operating system called iPhone OS — iPhone OS 3.2 to be precise — which was rechristened iOS with the release of version 4 later that year, to remove the device-specific naming. But at last year's WWDC, Apple decided to change the name of the iPad's operating system again to reflect the device's evolution, renaming it to iPadOS whilst retaining the iOS moniker for the iPhone.

The most apparent changes in iPadOS 13 concern the user interface and multitasking. However, I don't think these will be of much use for music and audio apps, since such apps rarely provide a Slide Over interface, although you'll still be able to access Slide Over-capable apps within an app. And similarly, I haven't seen any music or audio apps support side-by-side multitasking, making it unlikely we'll see multiple projects open side-by-side anytime soon as you can with, say, Word documents.

Of greater significance was the recent release of iPadOS 13.4, adding a seemingly contradictory feature to the iPad: comprehensive trackpad support. Pairing an iPad with a trackpad allows control of a cursor as if you were touching the screen with a finger, although this pointer support doesn't attempt to simply mimic a mouse (which is supported, though less desirable). The cursor is displayed as an easily visible translucent circle (except in certain contexts, such as editing text) when needed and uses inertia as is common on touch-based interfaces.

The trackpad supports multiple pointers, such that apps can take advantage of the extra input, and there are many multi-finger gestures built into the system. For example, you can swipe left or right with three fingers to switch between apps, or return to the Home screen by swiping up, also with three fingers.

The most significant change for music and audio apps in iPadOS 13 concerns the way apps communicate audio and MIDI data with each other. When the iPad first appeared, there wasn't an official way to stream audio between apps, whether it be for further processing in an effect app or as an ultimate end point, such as a recording app. To overcome this limitation, a third-party solution called Audiobus gained popularity, allowing audio and later MIDI to be routed and processed between apps. However, Apple decided to provide an official alternative, as they had done with the introduction of Core MIDI, for example, and introduced Inter-App Audio (IAA) in 2013 with iOS 7. However, although IAA could coexist with Audiobus, with the latter supporting the former, IAA actually offered less flexibility and functionality for the end user.

Rather than continue to support IAA, Apple decided to deprecate it in iPadOS 13 in favour of promoting the use of Audio Unit Extensions instead, which are like Audio Unit plug‑ins on Mac OS. Audio Units have been part of the system from early on, and Apple have gradually opened up their use within individual apps before allowing an app to use Audio Units implemented in other installed apps. Similarly, Extensions, which allow an app to use functionality from another app, were implemented in iOS 8, but Audio Units weren't included in this feature until iOS 9.

Although it's taken a while for all of the piece to fall into place, the use of version 3 Audio Unit (some referred to as AUv3) Extensions apps is now widely adopted by most host, instrument and effects apps. Developers can use this functionality can use a single app as a container for multiple Audio Unit Extensions, and such Audio Units can also implement MIDI-only effects, and in iPadOS 13 user presets created by an Audio Unit in one app are accessible by that Audio Unit in any app.

iPad Therefore iAm

Given the iPad's success, I've often wondered if Apple created a new product category for the industry or just within their own catalogue, since any attempt to imitate such a device has arguably produced a resounding failure. There's been the inevitable Android-based competition, such as Google's own ill-fated Nexus line or newer Pixel Slate models, or products like Samsung's Galaxy Tab range. But, other than perhaps Amazon using Android as the basis for the company's Fire tablets, these bids to compete with Apple haven't succeeded, largely due to a relatively weak and fragmented app ecosystem when compared to the App Store.

As it's turned out, the iPad's main competition isn't other tablets, but rather devices enabled by Mac OS or Windows. The starting price of an iPad Pro 12.9-inch (with its 6GB memory and 128GB storage) is the same as the latest entry-level MacBook Air, offering a 13-inch display, a Core i3 CPU, 8GB memory,and 256GB storage. And less powerful devices like Microsoft's Surface Go 2 (which starts at £399$399 for a Pentium Gold 4425Y, 4GB RAM, and 64GB storage), or even the entry-level Surface Pro 7 (with a Core i3, 4GB memory, and 128GB storage for £719$749), at least open you to the world of more feature-rich versions of Cubase, Reason, Live, Pro Tools, Reaper and so on.

However, an iPad is not a laptop, and I don't think Apple ever intend it to become one. For some use cases, such as working with the iPad purely as a surface for playing an instrument, or controlling an application running on another computer via an app, a touchscreen is all that's required. But in other cases, such as creating music in a more complex app, the value of the keyboard, trackpad and Pencil becomes apparent. Apple don't need to turn an iPad into a laptop computer, any more than they need to transform a laptop into an iPad — it's about providing the best experience for what you're trying to achieve in any given moment.

Therefore, whether it's because you want a device for recording an idea in a mobile environment or studio, a device that can provide remote control over your Pro Tools rig, or a device that becomes a tapestry for synths and effects, there are many situations where musicians and audio engineers will benefit from having an iPad.

Here's to the following decade, where your next studio might not be a studio...

iPad Pricing

- iPad: 32GB £349$329; 128GB £449$429. (Add £130$130 for Wi-Fi + Cellular)

- iPad mini (Wi-Fi): 64GB £399$399; 256GB £549$549. (Add £120$130 for Wi-Fi + Cellular)

- iPad Air (Wi-Fi): 64GB £479$499; 256GB £629$649. (Add £120$130 for Wi-Fi + Cellular)

- iPad Pro 11-inch (Wi-Fi): 128GB £769$799; 256GB £869$899; 512GB £1069$1099; 1TB £1269$1299. (Add £150$150 for Wi-Fi + Cellular)

- iPad Pro 12.9-inch (Wi-Fi): 128GB £969$999; 256GB £1069$1099; 512GB £1269$1299; 1TB £1469$1499. (Add £150$150 for Wi-Fi + Cellular)

One of two factors dictating prices within a given iPad line-up is storage, but how much is enough? As usual, you should buy as much as you can afford, but also with consideration to the apps you intend to use. For example, hosts and sample-based instruments are generally larger than synths and effects; GarageBand, Cubasis and Auria Pro (with the necessary content that's downloaded the first time the app is run) need 1.6GB, 1.2GB and 1.93GB respectively, while Korg's Module or IK Multimedia's SampleTank have base footprints of 1.3GB and 1.6GB. However, each Eventide effects app requires less than 25MB, and synths such as Moog Music's Model D take around 100MB.

'A' Is For iPad

When discussing the iPad, it's impossible not to mention Apple's series of custom chips beginning with the letter 'A', which are the engines that make these devices possible, starting with the A4 in the original iPad. Such a chip is known as a system-on-a-chip (often abbreviated as an SoC) because many or all of the components required to implement a computer are integrated on a single chip: CPUs, GPUs, memory controllers, input and output interfaces and so on. Therefore, it's no surprise that SoCs have become commonplace in the mobile world, where space and energy efficiency is at a premium compared to a traditional computer motherboard.

Apple have continuously improved these A‑series chips with newer versions designated by numerical increments, often baptised with an 'X' appendage to denote enhanced graphics processing. For example, while the iPad 2's A5 chip boosted overall performance with dual CPU and GPU cores, the device had the same 1024 x 768 resolution as the inaugural iPad. However, the third-generation iPad — the first iPad to feature a so-called Retina display with a higher 2048 x 1536 resolution — featured an A5X chip with a quad-core GPU to aid in processing the increased number of pixels.

More recently, Apple have added adjectives like 'Fusion' and 'Bionic' to the naming schemes, although these are mostly applied to communicate improved performance from a marketing perspective.

Who Wants A Stylus?

When Steve Jobs introduced the iPhone in 2007, he dismissed the use of a stylus as the input method for the device by asking: "Who wants a stylus?" further explaining his contempt by saying "You have to get them and put them away and you lose them. Yuck! Nobody wants a stylus... We're going to touch this with our fingers." Therefore, given the iPad was based on a similar user interface to the iPhone, it was no surprise it also followed this lack-of-stylus paradigm for its interaction. Unlike the iPhone, though, after a few years it was becoming obvious to some that perhaps fingers weren't enough to fully exploit the iPad.

As mentioned in the main text, the Apple Pencil was introduced as an accessory for the original iPad Pro, although today it's compatible with every iPad model the company sell. It's able to measure position, pressure and tilt data, and communicate this to your iPad over Bluetooth, offering a level of precision previously not possible with an iPad. It turned out people did want a stylus.

The only flaw was how to charge it. Revealed by an easily removable (and therefore losable) cap at the rear of the Pencil was a Lightning connector, which paired and charged the Pencil when inserted. And while an equally losable, small adaptor was included to plug the Pencil into a Lightning cable and charger, Apple presumably figured most users would just plug the Pencil into the bottom of their iPad for charging. This method always left you with the worry you'd accidentally knock the iPad and break the Lightning connector (something I didn't try), but it seemed as good an idea as putting the Lighting connector underneath the Magic Mouse for charging.

Pen2Bow allows you to use an Apple Pencil as a MIDI controller with a modern iPad.A few unique apps have embraced the Pencil, such as Pen2Bow (£7.99$7.99), which allows the Pencil to be used as a MIDI controller and this is rather fun. There's also been support, varying in quality and approach, in music notation apps. StaffPad (reviewed in the June issue) is now available on the iPad using the Apple Pencil as its primary input source. And existing iPad notation apps have added support via in-app purchases, such as Symphony Pro, where for £14.99$14.99 you can easily select notes or, much like StaffPad, draw in an active bar and the input will be translated. If you're a Notion user, £7.99$7.99 enables handwriting input to be selected where a separate input stave is displayed for Pencil input. Unlike StaffPad, both these options can be used without the Apple Pencil, although you won't get the benefits of an active, Pencil-like input such as precision or palm rejection.

Pen2Bow allows you to use an Apple Pencil as a MIDI controller with a modern iPad.A few unique apps have embraced the Pencil, such as Pen2Bow (£7.99$7.99), which allows the Pencil to be used as a MIDI controller and this is rather fun. There's also been support, varying in quality and approach, in music notation apps. StaffPad (reviewed in the June issue) is now available on the iPad using the Apple Pencil as its primary input source. And existing iPad notation apps have added support via in-app purchases, such as Symphony Pro, where for £14.99$14.99 you can easily select notes or, much like StaffPad, draw in an active bar and the input will be translated. If you're a Notion user, £7.99$7.99 enables handwriting input to be selected where a separate input stave is displayed for Pencil input. Unlike StaffPad, both these options can be used without the Apple Pencil, although you won't get the benefits of an active, Pencil-like input such as precision or palm rejection.

A redesigned, second-generation Apple Pencil was unveiled with the third-generation Pro, and remains compatible with the new iPad Pro. There were many improvements, such as the ability to for an app to recognise a double-tap on the touch-sensitive straight edge of the new Pencil — a feature many apps have used to toggle between input and erase modes. But, more usefully, it now magnetically attaches to the side of you iPad for pairing and charging.

The first-generation Apple Pencil for all non-Pro iPads costs £89$99, whereas the second-generation of the accessory for the iPad Pro is priced at £119$129.

It's A Kind Of Magic

In addition to describing the iPad as magical, Apple also offer several accessories with the Magic prefix initially developed for the Mac. The most germane of these accessories is the Magic Trackpad 2, which is compatible with any iPad since 2015's iPad mini 4 and fully supports the pointers introduced in iPadOS 13.4. Available in either Silver or Space Grey finishes to ensure concordance with your iPad, at £129$129 or £149$149 it's not the cheapest Bluetooth trackpad, but it's probably the best. The edge-to-edge glass surface with Force Touch provides a smooth feel and effortless operation, handling multi-finger gestures with the gracefulness of a swan.

My only quibble is the Lightning connector used for charging. Because, although a short USB‑A to Lightning cable is included, users of recent iPad Pros with USB‑C will need an adaptor or separate cable, and possibly an extra charger. When asked about this, Apple replied saying "We wouldn't have any additional info on what future plans might look like. But of course we make a range of charging options." However, since the company have spent years shepherding us to a USB‑C- future, this is likely a temporary situation. In the meantime, though, it's frustrating that Pro users might need to purchase an extra item that becomes something else to pack when you're on the go.

The Magic Keyboard's cantilever hinge makes the adjustable magic possible.However, Apple's response also pointed me to another option: the new Magic Keyboard for iPad Pro, available in two sizes to accommodate the 12.9- and 11-inch third and fourth-generations. The Magic Keyboard features a keyboard, trackpad and USB‑C pass-through port for power, so you can charge the iPad whilst using its USB‑C port to connect other peripherals. It's also both a stand and cover, with an opening in the back for the cameras and sensors, and feels sturdy when closed, although slightly heavier than you might anticipate.

The Magic Keyboard's cantilever hinge makes the adjustable magic possible.However, Apple's response also pointed me to another option: the new Magic Keyboard for iPad Pro, available in two sizes to accommodate the 12.9- and 11-inch third and fourth-generations. The Magic Keyboard features a keyboard, trackpad and USB‑C pass-through port for power, so you can charge the iPad whilst using its USB‑C port to connect other peripherals. It's also both a stand and cover, with an opening in the back for the cameras and sensors, and feels sturdy when closed, although slightly heavier than you might anticipate.

There's an unexpected stiffness when you open the Magic Keyboard, especially apparent if you try opening it with your hands in mid-air. But it clicks satisfyingly into its steepest angle, and the iPad Pro is magnetically held in place on a stand incorporating a cantilever hinge, giving the illusion your device is floating above the keyboard. This hinge is adjustable to a 130-degree angle, although it's perhaps a shame it can't be lowered with a gentler gradient like Microsoft's Surface kickstand. The backlit keyboard, based on a scissor mechanism with 1mm travel, provides a superb mobile typing experience, and the trackpad, whilst smaller than those employed by other Apple products, supports Multi-Touch gestures and you'll swiftly acclimatise to it.

The Magic Keyboard is elegantly designed and engineered and deserving of its name. But when I saw the price, I felt like a retromingent raccoon: £349$349 for the 12.9-inch iPad Pro, or £299$299 for the 11-inch variant! Now, Apple accessories can be tad pricier than the competition, but £349$349 for what amounts to a cover and a stand with a built-in trackpad and keyboard? That makes the 12.9 inch accessory asmore expensive asthan the entry-level iPad! And that's not the only problem: to try one is to want one.

Apple also offer an updated Smart Keyboard Folio, with two viewable angles and space for the new camera system. The dome-switch keyboard, finished with a woven fabric covering, delivers a typing experience as comfortable and convenient as a concrete pillow. However, the 12.9-inch version feels easier to type with than the smaller option for the 11-inch Pro. Costing £179$179 and £199$199 depending on the size, the price of a Smart Folio Keyboard with Magic Trackpad 2 is basically the same as a Magic Keyboard. So yes, I'm already defending its cost.

The Smart Keyboard lives on as a £159$159 accessory for the iPad Air and iPad (or older 10.5-inch Pro). Offering just a single angle with a Folio-like keyboard, I'd recommend trying before buying to conclude whether it's right for you.

As a footnote, a keyboard isn't just for typing, as those who make use of keyboard shortcuts in applications designed for conventional computers will know. You'll be surprised how often you try pressing the space bar to play/pause the transport in an app after attaching a keyboard to your iPad. An iPadOS OS app will publish a list of shortcuts that appear when you hold down the command key, although keyboard support is currently fair-to-middling in music and audio apps. While Apple's own GarageBand is a first‑class citizen in this area, as you might expect, most are not.