Multichannel PCI‑card based digital audio recording systems are increasingly common these days, but not all of them focus on the quality of the onboard converters to the extent they should. Dave Shapton checks out a new card from far‑sighted digital problem‑solvers Aardvark that promises not to throw out the baby with the bathwater.

If you've been involved in recording (and reading SOS regularly) for the past few years, you won't have failed to notice that for some time now, desktop computers have been capable of taking over the recording functions that were traditionally associated with dedicated studio hardware. For example (so the theory goes, anyway), many current PCI computer soundcards have everything required to turn your computer into an all‑digital 'recording studio in a box'. Add a latest‑generation MIDI + Audio recording/editing software package, and you might begin to wonder why you would need any 'traditional' hardware in your studio.

In reality, though, there is a world of difference between what you can achieve with the 'everything in a single computer' approach and what is expected of a professional studio. Of course, you do find desktop computers in top‑notch studios, but they don't use 'multimedia' soundcards — and they aren't expected to do everything.

So why can't you necessarily expect top‑end performance from a soundcard‑based computer studio? After all, if it's all digital, shouldn't the sound be great regardless of the platform? Well, one of the problems is that 'real' sound sources (ie. acoustic ones, such as guitars and people's voices, as opposed to electric or electronic ones), are not digital. They have to be converted from analogue sound to digital data, and that is actually something that a conventional PC soundcard typically does rather badly.

<!‑‑image‑>Let's say you have a 16‑bit soundcard in your PC. What this means is that a signal that stops just short of overloading the input to the card will result in a digital output peaking at 16‑bit resolution. Lower‑level signals are encoded with fewer bits and it is often the case that the bits representing the lowest signal levels do nothing at all, but just flip randomly, creating noise. Added to this is the cacophony picked up by the analogue part of the soundcard from the computer itself (in audio terms, the inside of a computer is just about the worst possible environment, because almost everything that happens in there generates a spike or a square wave). Listen critically to the audio outputs of almost any soundcard with onboard converters and you will be shocked at the level of computer‑generated noise.

What's the answer? Well, one idea is to locate all vestiges of the analogue world outside the computer: and that includes the analogue‑to‑digital and digital‑to‑analogue converters. I've been arguing for a long time now that as the audio business converges with the computer industry, the focus of audio skills will need to be directed at programming, and designing high‑quality input/output devices. This prophecy seems slowly to be coming true, and the new Aardvark Aark 20/20, which styles itself as a Professional 20‑Bit Multitrack Hard Disk Recording System, is clear evidence of this.

What You Get

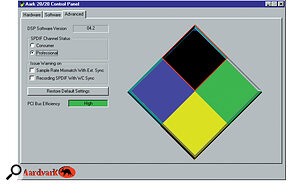

Figure 1: The supplied 20/20 Control panel tests your PC's likely multitrack capability. Mine, as you can see here, rated 'High'.

Figure 1: The supplied 20/20 Control panel tests your PC's likely multitrack capability. Mine, as you can see here, rated 'High'.

Aardvark is a small American pro audio company based in Michigan, USA. They already have a healthy reputation as producers of the AardSync II low‑jitter master digital audio clock generator for high‑end digital audio workstations (reviewed in SOS October '97) and some low‑jitter clock distribution equipment.

The Aark 20/20 system consists of a very solid, nicely made PCI card with an onboard DSP chip (the so‑called Host card) and an external box containing eight channels of both 20‑bit A‑D and D‑A conversion. S/PDIF in and out is also provided, and can be used at the same time as the eight channels of analogue I/O, giving a total of 10 channels that can be used simultaneously. Software drivers for Windows 95 allow audio applications to 'see' the Aark 20/20 as if it was five stereo soundcards, so most modern software should work just fine with it. To get you started, the card is bundled with Samplitude Studio audio recording package from the German Company SEK'D.<!‑‑image‑>

Installation

Figure 2: The Control panel's Hardware screen is where you can set up the 20/20's internal routing options, adjust individual channel volumes, and keep an eye on the levels with the real‑time meters.

Figure 2: The Control panel's Hardware screen is where you can set up the 20/20's internal routing options, adjust individual channel volumes, and keep an eye on the levels with the real‑time meters.

I have to say that this is one of the easiest audio products I have ever installed. Having a virgin Windows installation with no other exotic PCI cards (apart from a generic S3‑based video card) probably helped, but I have had enough nightmares with other audio devices to make me grateful for a nice, clean, simple installation. In case you have never installed a product like this, the documentation supplied is helpful, with several screenshots showing how it is done.

I tested the installation routine on both Windows 95 and Windows 98 and found both to work equally well. There are no Windows NT 4.0 drivers yet, but they are being worked on, and ASIO drivers are close to release, which will boost the product's responsiveness with Cubase VST.

The supplied Aardvark software control panel (from which the screen dumps that adorn this article are taken — see Figure 1) tests your PC's suitability for multitrack audio work by testing the efficiency of the PCI buss. The PCI capacity of my generic Pentium II 266MHz was rated as 'High'. This means my system should be able to simultaneously record and play back 10 channels of digital audio, assuming I have a fast enough hard drive. Once the Host card is installed, a single 2‑metre shielded 25‑pin cable connects the PCI card to the back of the Aark 20/20 converter box. This cable also provides power to the external unit. Most PCs are populated with at least one other 25‑pin socket, so some care is needed to find the right connection (I'm rather sensitive about this sort of thing, because I once blew up a motherboard by confusing a SCSI port with a printer socket...)

The sturdy external unit has two rows of eight quarter‑inch connectors on the front, with outputs on top and inputs below. Beside these are phono sockets for S/PDIF in and out. On the back, along with the host PCI card cable, are BNC connections for word clock in and out, together with a BNC connection for video in, ready for a future upgrade to enable the Aark 20/20 to derive its master sampling rate from an external video signal. The word clock out can be used to synchronise the Aark 20/20 with other digital audio devices, including a second Aark 20/20. Indeed, the software automatically recognises the presence of a second unit and configures itself for 16 tracks of analogue I/O instead of eight.<!‑‑image‑>

DSP & Routing

The system comes complete with onboard digital signal processing; but the Aark 20/20 makes no claim to be a digital effects device. The DSP is actually used to increase the flexibility of the 20/20 in some very useful ways. Firstly, it can behave as a digital patchbay; any input can be routed to any or every output via the software control panel. In the digital domain, it's easy to route a single input to multiple outputs; but if you want several sources to be routed to a single destination, then you need digital signal processing. Although the Aark 20/20's main role in life is to get eight discrete analogue outputs to an external mixer, the ability to create submixes and a separate monitor mix within the unit is incredibly useful. The monitor mix is a separate function and can itself become an input source for a piece of recording software. This means that you can use it to mix all eight inputs (or all 10 if you use the S/PDIF inputs as well) into stereo and then place them on just one pair of tracks in your software recording application. The level of each track can be controlled individually, and there is a master mix volume control as well, and a pan control is planned for the next version of the software (see Figure 2). You could also use the application itself as the monitor signal source and have the Aark 20/20 bounce up to 10 tracks to another pair of tracks. The monitor function is best seen as an "eavesdropping" device that stops short of being a fully functional mixer. It is, though, an extremely handy utility.

Another use for the DSP on the Aark 20/20 is to generate a test tone. All outputs can select 'Tone' as an option: very useful when you are setting the system up and just want to check signal paths and levels. 'Silence' is another DSP option that has less obvious uses, but can be used to demonstrate the noise floor of the system if it is selected as a signal source. The software control panel supplied with the Aark 20/20 is visually unexciting, but this is hardly a problem when you consider that its main function is to set up the routing of the inputs, outputs and monitor buss. Three tabs at the top of the control panel let you configure the hardware, software and advanced settings such as professional or consumer S/PDIF (some DAT machines are very fussy about the somewhat superfluous tag in the S/PDIF bitstream that distinguishes between the two formats). The software tab reveals what I mentioned earlier; that the Aark 20/20 appears to a recording application as five stereo soundcards. This is becoming common practice with multitrack soundcards and is a good way to gain compatibility with the largest number of applications. I noted that when the Aark 20/20's control panel was maximised, it consumed a significant portion of my PC processor's number‑crunching capability. It looks to me as if this is due to the real‑time meter display. It's not a problem as long as you don't maximise the control panel while you are playing back a lot of tracks.

Never Mind The Bits, Feel The Quality

The big advantage the Aark 20/20 has over other PC multitrack I/O units is that the converters are outside the PC. This should lead us to expect a very low noise floor, since all of the sensitive analogue parts are well away from the PC and shielded from it. When I test converters I always make a point of listening closely to the amount and type of noise output when there is no signal present. On a typical PC soundcard with internal converters, you don't have to raise the monitor levels very far before you begin to hear a din that resembles an electronic dawn chorus. Not so with the Aark 20/20. At all normal listening levels, the output seems completely silent. At the very highest gain settings, some noise can be heard, but even then it is just that — noise, with some, but very little, of the 'graininess' that seems almost inevitable with digital converters. Overall, then, this is a very quiet unit.

As far as the audio quality is concerned, I have to say that these converters have very little sound of their own; but then that's exactly what you want from converters! Sure, I wasn't listening in a perfect environment, but my setup is probably typical of a digital project studio: £400 studio nearfield monitors, good speaker stands and good cables, in a well damped room. The gain through my review 20/20 was a few dB less than unity, so it was difficult to make a direct comparison by switching the unit in and out, the problem being that the difference in volume completely masked any qualitative difference there may have been. (I didn't want to introduce any additional gain stages to compensate, because that would have affected the sound as well). With practice, I found I could make the switch and adjust the volume all in one action, thereby giving me a valid comparison between direct audio and audio through the Aark 20/20.

Essentially, then, these converters are very nearly transparent. If my life depended on my being able to describe the effect they had on the sound then, yes, the bottom end lost a little clarity. But to put this in perspective — I had to cascade all eight inputs and outputs to confirm that this was the case. Even with the audio undergoing four conversions from A‑D and D‑A (I wanted to keep the signal stereo) the result was still better than some converters manage after just one conversion! At all times, the sound was remarkably smooth; lacking any sort of harshness, yet never short on detail.

The Final Word

Aardvark is a company that makes products to solve digital audio problems. It is clear from the design and quality of the Aark 20/20 that they know about digital audio. Apparently, hidden under a sealed cover on the Host card is a technology unique to Aardvark that uses digital signal processing to reduce jitter, which is one of the most insidious forms of distortion in digital audio. It is this kind of attention to detail that you should take into account when choosing a multichannel converter. You shouldn't base your decision just on the number of inputs and outputs. After all, you don't choose a car because it's got four wheels, do you?

Pros

- Very solidly built.

- Transparent sound.

- Built‑in I/O routing matrix.

Cons

- Doesn't offer some of the software 'bells and whistles' of its multichannel competitors.

Summary

With its high‑quality 20‑bit converters and simple‑to‑use but fully‑featured control panel software, the Aark 20/20 is ideal for use as the basis of a digital recording system. All it really lacks at present are native drivers for specific audio recording applications, but even these are on their way.