iZotope Neutron’s main interface, showing the five reorderable modules at the top, the controls for Compressor 2 in the central editing pane, and on the right-hand side the Limiter with the Neutrino spectral-shaping controls below it.

iZotope Neutron’s main interface, showing the five reorderable modules at the top, the controls for Compressor 2 in the central editing pane, and on the right-hand side the Limiter with the Neutrino spectral-shaping controls below it.

iZotope say that Neutron not only has the processing power to address all sorts of mixing issues, but the intelligence to help you identify them.

For a while now, the bundled plug-ins in most mainstream DAWs have provided ample bread-and-butter processing facilities, so a lot of third-party plug-in manufacturers are focusing their development efforts on products that offer a time-saving advantage — for example, by creating ever more user-friendly metering and interfacing, or by working out ways to automate labour-intensive manual mixing tasks. The stir caused by iZotope at the Audio Engineering Society’s recent convention in Los Angeles provided further evidence for this trend, as most of the buzz about their Neutron plug-in launch centred not on the software’s audio-manipulation capabilities, but on two innovations aimed at speeding up the user’s workflow: a Masking Meter to help locate psychoacoustic frequency clashes between different instruments in your mix and, more intriguingly, a Track Assistant designed to custom-generate promising-sounding initial processing chains automatically in response to the characteristics of your source audio.

Since returning from the show, the question I’ve been peppered with most often (after “Where the hell have you been for the last week?!”) has been “Have you tried Neutron, and does it really work?” Well, I have now had the opportunity to give Neutron a thorough going-over, but I can’t really tell you whether it’ll meet your expectations without first explaining a bit more about the nuts and bolts of how it works...

Five Go Processing

Neutron’s Compressor module provides several advanced per-band features that significantly expand its usefulness: a ‘bottom-up’ compression option (shown by the bracketed ratio value), a wet/dry mix control, and an independent frequency-tailored side-chain input.At Neutron’s heart is a chain of five processing Modules: an Equalizer, two Compressors, an Exciter and a Transient Shaper. These can be dragged into any order you like, and the more expensive ‘advanced’ version of Neutron provides the individual modules as stand-alone plug-ins too, as well as featuring 7.1 surround-sound support. Presets are available both for the whole plug-in and for individual modules, and there’s a nifty Undo History window which lets you instantly compare up to four different custom settings.

Neutron’s Compressor module provides several advanced per-band features that significantly expand its usefulness: a ‘bottom-up’ compression option (shown by the bracketed ratio value), a wet/dry mix control, and an independent frequency-tailored side-chain input.At Neutron’s heart is a chain of five processing Modules: an Equalizer, two Compressors, an Exciter and a Transient Shaper. These can be dragged into any order you like, and the more expensive ‘advanced’ version of Neutron provides the individual modules as stand-alone plug-ins too, as well as featuring 7.1 surround-sound support. Presets are available both for the whole plug-in and for individual modules, and there’s a nifty Undo History window which lets you instantly compare up to four different custom settings.

The sheer range of audio-processing facilities on offer in Neutron can seem a bit daunting at first, so to start with let’s get our bearings by looking at each processing block’s self-contained features. The Equalizer offers 12 filters in total (high-pass, low-pass, high and low shelves, and eight peaking bands) with frequency control, a useful range of shapes/slopes and, in most cases, adjustable bandwidth. Most of the filter types can also be switched to dynamic compression/expansion operation, with per-band Threshold control.

All three of the other modules are three-band types, each with independent band-split frequencies. The two Compressor modules are identical, with traditional Threshold, Ratio, Attack, Release and Gain controls alongside plenty of more advanced extras. For example, the ratio has an adjustable soft knee and can be applied not only ‘top down’ (ie. squashing peaks), but also ‘bottom up’ (ie. peaks are left unscathed while sub-threshold signals are boosted), the latter not dissimilar in sound to parallel compression. The extremely generous range of time constants will happily take you into distortion territory should you choose, but an auto-release mode (based on the user’s own Release setting) can also fast-track you to more transparent-sounding results. A three-way selector switched the module’s peak-detection characteristics between RMS, Peak and True (a kind of frequency-compensated RMS variant), and there’s a pair of resonant pass filters on hand in the side-chain if necessary. Punch in the new ‘Vintage’ mode, and you get a blend of attributes associated with various outboard ‘elder statesmen’, but with wide enough parameter ranges to allow in-depth tailoring if what you hear at first doesn’t float your boat.

An X-Y control makes it easy to create custom blend between the Exciter module’s four different flavours of saturation enhancement.The Exciter gives four different distortion flavours, each with its own recipe of added harmonics and dynamic response. For each frequency band you can choose how hard you drive its distortion engine, how you mix the different distortion flavours (via an X-Y matrix familiar to users of iZotope’s Alloy), and how much of the distortion you mix in. Besides the per-band controls, there’s a global pre-emphasis switch with three preset low/high-mid-range contours, and a high-frequency shelving cut to rein in any excessive brightness when you’re driving things hard. The multiband attack/sustain processing of Transient Shaper is functionally very straightforward, but offers additional scope for adjustment in the form of time-constant presets, both per-band (Sharp/Medium/Smooth) and globally (Precise/Balanced/Loose), which is a welcome development from the more basic implementation in Alloy 2.

An X-Y control makes it easy to create custom blend between the Exciter module’s four different flavours of saturation enhancement.The Exciter gives four different distortion flavours, each with its own recipe of added harmonics and dynamic response. For each frequency band you can choose how hard you drive its distortion engine, how you mix the different distortion flavours (via an X-Y matrix familiar to users of iZotope’s Alloy), and how much of the distortion you mix in. Besides the per-band controls, there’s a global pre-emphasis switch with three preset low/high-mid-range contours, and a high-frequency shelving cut to rein in any excessive brightness when you’re driving things hard. The multiband attack/sustain processing of Transient Shaper is functionally very straightforward, but offers additional scope for adjustment in the form of time-constant presets, both per-band (Sharp/Medium/Smooth) and globally (Precise/Balanced/Loose), which is a welcome development from the more basic implementation in Alloy 2.

Sounds Promising

iZotope have updated the multiband transient processing from their Alloy 2 plug-in for Neutron, adding new global and per-band time-domain parametersFrankly, none of Neutron’s higher-concept functions would be worth a brass farthing if the core audio processing was ropey, so I’m delighted to report that it doesn’t disappoint — no surprise given iZotope’s existing track record. There’s enough sonic firepower to radically transform the personality of sounds you don’t like, enough precision to target mix minutiae with confidence, and enough musical sensibility to deliver results that appeal on both a subjective and technical level.

iZotope have updated the multiband transient processing from their Alloy 2 plug-in for Neutron, adding new global and per-band time-domain parametersFrankly, none of Neutron’s higher-concept functions would be worth a brass farthing if the core audio processing was ropey, so I’m delighted to report that it doesn’t disappoint — no surprise given iZotope’s existing track record. There’s enough sonic firepower to radically transform the personality of sounds you don’t like, enough precision to target mix minutiae with confidence, and enough musical sensibility to deliver results that appeal on both a subjective and technical level.

Metering facilities are generous, with level, spectrum and gain-change displays in abundance, and some useful ways you can adapt what they show and how they show it. But the usefulness of the whole system is expanded even further because all the modules, and every frequency band within the Compressor and Exciter, have separate wet/dry mix sliders. At a stroke, this makes it child’s play to adjust the relative ‘severity’ of your different processing blocks, as well as breathing new life into the preset library, allowing over-egged ‘demo fodder’ settings to quickly be brought within bounds of real-world applicability and taste. Furthermore, Neutron manages all this within a pretty reasonable CPU footprint, so you should be able to use it pretty much however often your mix needs.

Mind you, I wouldn’t go quite as far as saying that Neutron’s the only processing plug-in you’ll ever need. I’d have liked a bit more than just a gain slider for input conditioning, for instance — just basic stereo width and polarity/phase controls would have saved me loading in other plug-ins — and I also missed ratio, attack and release controls on the dynamic EQ bands. (Don’t tell me it’s a GUI space issue, given Ozone’s status as record-holder for ‘number of parameters on a single grain of rice’.) I’ve also heard smoother high-frequency EQ boosts, to be honest, and found myself searching elsewhere for more ear-friendly brightness and ‘air’ enhancements on occasion.

Mind you, I wouldn’t go quite as far as saying that Neutron’s the only processing plug-in you’ll ever need. I’d have liked a bit more than just a gain slider for input conditioning, for instance — just basic stereo width and polarity/phase controls would have saved me loading in other plug-ins — and I also missed ratio, attack and release controls on the dynamic EQ bands. (Don’t tell me it’s a GUI space issue, given Ozone’s status as record-holder for ‘number of parameters on a single grain of rice’.) I’ve also heard smoother high-frequency EQ boosts, to be honest, and found myself searching elsewhere for more ear-friendly brightness and ‘air’ enhancements on occasion.

Mask, And You Shall Receive...

Beyond the fundamental quality and power of the audio processing, Neutron also scores extremely well in terms of how its modules can interact at mixdown — most notably, of course, via the headline-grabbing Masking Meter. (If you’ve never heard the term ‘masking’, check out the ‘What’s Masking?’ box for a brief introduction.) Click the Masking button in any mixer channel’s Neutron Equalizer module, select any other Neutron plug-in instance from the adjacent drop-down menu, and you’ll suddenly see two different frequency-specific visual representations of how much the current channel is being masked by the menu-selected one:

- Vertical sections of the spectrum analyser display’s black background bleach out in real time wherever masking occurs; the whiter any section of the frequency response becomes, the stronger the masking. Typically this results in an undulating display that looks a bit like a punch-up behind a thick curtain!

- A further display strip above the spectrum analyser pane shows a histogram (a ‘bar graph’ to its mates) of the number of ‘frequency collisions’ between the two tracks. These can be averaged over a 500ms or 3000ms window (the latter the default) or tallied indefinitely, and you can reset the bars individually or globally, depending on where you click the histogram strip.

Handily, if both the plug-in instances happen to include an Equalizer module, then both EQ curves (complete with spectrum-analysis displays) can also be seen and controlled directly from the single Masking Meter GUI, which means you don’t just see where masking’s happening: you can start doing something about it straight away by cutting or boosting appropriate spectral regions for either sound. In fact, there’s even a rather nifty Inverse Link mode, whereby any gain boost applied to one of the sounds is automatically mirrored by a corresponding cut with the same-numbered band on the other sound, the idea being to reduce masking at that frequency with minimal change to the spectral balance of the mix as a whole.

Alongside the Masking Meter is a little Sensitivity slider that works just as you’d expect, increasing the number of identified areas of masking, as well as the brightness/height of the two displays at the relevant frequencies. In addition, though, you’ll find another Gain Offset setting squirrelled away under the Equalizer tab of Neutron’s separate Options window. This independently adjusts the level feeding the Masking Meter, without affecting the audio processing at all, and the reason for its existence needs a little explanation.

First of all, it should be fairly self-evident that masking is level-dependent: the quieter a sound, relatively speaking, the more it’s masked by other sounds in the mix. Now, because Neutron is designed to be an insert effect within your DAW software, it will normally occupy a pre-fader position in the virtual software mixer, so its Masking Meter can’t actually know what mix level you’ve chosen (using your channel fader) for the processed audio. The purpose of Neutron’s Gain Offset parameter is to offset the Masking Meter’s input level for each plug-in instance so it matches its host channel’s fader setting, and thereby achieves the most accurate masking indications.

Neutron’s new Masking Meter in action on an electric guitar track, showing how a piano track elsewhere in the mix is competing with it in the frequency domain. The red Histogram display across the top keeps a tally of the number of frequency collisions within a user-definable time window, while the bleaching out of the guitar’s spectrum display below it indicates the amount of masking going on in real time. The lower spectrum display and EQ curve belong to the piano track, allowing you to conveniently tweak the equalisation on both channels from a single plug-in window.

Neutron’s new Masking Meter in action on an electric guitar track, showing how a piano track elsewhere in the mix is competing with it in the frequency domain. The red Histogram display across the top keeps a tally of the number of frequency collisions within a user-definable time window, while the bleaching out of the guitar’s spectrum display below it indicates the amount of masking going on in real time. The lower spectrum display and EQ curve belong to the piano track, allowing you to conveniently tweak the equalisation on both channels from a single plug-in window.

Well, that’s the theory at least. In the event, it’s hardly a very robust workaround, based as it is upon a number of questionable assumptions. What if, for example, you have other channel plug-ins inserted post-Neutron? Or you’ve automated the channel fader? Or you’ve bussed Neutron-equipped tracks together for further balancing before they hit the mix bus? Or if you’re using some kind of Michael Brauer-style multi-bus master-compression routine? In short, I don’t think this Gain Offset dodge would have worked properly for any mix I’ve ever done! Not that I think it’s a huge deal, though, because even in some kind of Fisher Price ‘My First Mix’ where the Masking Meter could operate flawlessly, it still wouldn’t tell you anything tremendously concrete about how to EQ. You see, all it’s ever going to show is where masking’s actually happening, not where masking should or, more importantly, shouldn’t be happening!

That’s no criticism of iZotope, of course, because their programmers simply can’t be expected to predict what aspects of each instrument I want to hear most clearly in my mix. For example, if I find that all the horrible-sounding spectral regions of an acoustic guitar part are being heavily masked by the piano in my mix, then I’ll happily leave the EQ alone! And if I love the ‘crunch’ of my electric guitars at 800Hz, then why shouldn’t I let that mask the lead singer, and perhaps then push the vocal more strongly at 1.5kHz instead? In this light, I can think of few things better calculated to kill a mix stone dead than trying to use the Masking Meter to apply anti-masking EQ in some kind of technical or systematic way, no matter how effective Neutron’s display coding is.

Once you acknowledge those caveats, however, this feature still has a lot to recommend it as a mixdown time-saver. If masking from your piano part is leaving the lead vocal seem a bit buried, but you’re not sure where to EQ, it only takes a quick waggle of the lead vocal channel’s Sensitivity slider to reveal a couple of the most likely frequency ranges. You’ll still have to evaluate these suggestions by ear while EQ’ing, but you’ll usually get where you want to be more directly. Furthermore, I think the ear-training value of the Masking Meter shouldn’t be underestimated either. The way in which EQ cuts on one track affect the perceived tone of other tracks can take a while to appreciate for less experienced mix engineers, and Neutron presents a very tidy environment within which to develop experience of such masking effects.

Side-chain My Heart

Ironically, given the column inches it seems to have generated, I didn’t actually find the Masking Meter as useful as another Neutron feature that allows it to interact with other channels in your mix: its side-chain inputs. Nowadays, most of us are used to the idea of triggering a traditional full-band dynamics processor from an external key signal — a well-known application being to duck the level of a bass guitar whenever a kick drum hits, for example, as a means of maintaining more even low-end levels. What is much less common, though, is the kind of implementation we see here, where all 10 dynamic EQ bands and all six compressor bands offer external side-chain access. How about using your lead-vocal signal to trigger a couple of bands of dynamic EQ on your electric guitars, ducking only their heaviest vocal-masking frequencies, and only when the vocalist’s singing? That kind of thing is a walk in the park with Neutron.

Most of the Equalizer module’s filter types can be switched to dynamic operation, and will operate in either compressor or expander mode. The per-band side-chain input allows for a range of mind-bending mix-salvage stunts, although unfortunately there are no ratio, attack or release controls to refine the gain-change characteristics.Furthermore, you can route a given band’s side-chain input through the side-chain filtering associated with a different band in the same module, which opens up all sorts of seriously freaky mix stunts. For instance, I had a Mix Rescue submission once where the sibilance only became overbearing when it combined with the drum loop’s open hi-hat. At that time, the only solution I could come up with was to manually automate an EQ to duck the offending sibilants. With Neutron on the vocal track, however, I could have fed the side-chain of one dynamic EQ band (set at a suitable vocal de-essing frequency) from the drum loop track, filtering that side-chain signal through another inactive dynamic EQ band (set to a frequency which isolates a hi-hat trigger signal). Result: whenever a hi-hat appeared in the drum loop, it would have triggered additional vocal de-essing. Now I realise I may never encounter this once-in-a-blue-moon scenario ever again, but the fact is that Neutron would have handled it with ease, and could just as effectively have overcome many of the thorniest mix-balancing problems I’ve encountered in project studios.

Most of the Equalizer module’s filter types can be switched to dynamic operation, and will operate in either compressor or expander mode. The per-band side-chain input allows for a range of mind-bending mix-salvage stunts, although unfortunately there are no ratio, attack or release controls to refine the gain-change characteristics.Furthermore, you can route a given band’s side-chain input through the side-chain filtering associated with a different band in the same module, which opens up all sorts of seriously freaky mix stunts. For instance, I had a Mix Rescue submission once where the sibilance only became overbearing when it combined with the drum loop’s open hi-hat. At that time, the only solution I could come up with was to manually automate an EQ to duck the offending sibilants. With Neutron on the vocal track, however, I could have fed the side-chain of one dynamic EQ band (set at a suitable vocal de-essing frequency) from the drum loop track, filtering that side-chain signal through another inactive dynamic EQ band (set to a frequency which isolates a hi-hat trigger signal). Result: whenever a hi-hat appeared in the drum loop, it would have triggered additional vocal de-essing. Now I realise I may never encounter this once-in-a-blue-moon scenario ever again, but the fact is that Neutron would have handled it with ease, and could just as effectively have overcome many of the thorniest mix-balancing problems I’ve encountered in project studios.

A Helping Hand?

One down side of Neutron’s powerful and surgical processing facilities, though, is that they present the less technically minded user with an awful lot of controls. Most plug-in manufacturers mitigate this problem by providing a wide range of themed presets (often sorted by instrument, genre, and/or mix function), in the hope that more intuitive engineers can speedily find a useful starting patch that’s only a handful of parameter-twiddles from what they’re specifically seeking. iZotope have taken this idea a step further with Neutron’s unique Track Assistant function, which analyses the audio running through it and then automatically suggests a tailored processing scheme.

You can influence Track Assistant’s processing suggestions via two three-way parameters: Mode, which sets how heavy the processing will be; and Preset, which sets the character of the processing in a very generalised way.The way it works is that you first tell Track Assistant’s parameter-generation algorithm two things: how heavily you want to process (the Mode parameter, with Subtle, Medium and Aggressive settings) and what general style of processing you require (the Preset parameter, with Broadband Clarity, Warm & Open, and Upfront Midrange options). Then you play your project and set the detection algorithm going, whereupon the interface partially greys out and you’re treated to tantalising glimpses of various parameters zipping around under their own steam in the background. After four to 10 seconds, out pops your freshly baked Neutron setting, comprising custom settings for the Equalizer and Exciter, both Compressor modules and the Neutrino processor. (The Transient module, curiously, is omitted.)

You can influence Track Assistant’s processing suggestions via two three-way parameters: Mode, which sets how heavy the processing will be; and Preset, which sets the character of the processing in a very generalised way.The way it works is that you first tell Track Assistant’s parameter-generation algorithm two things: how heavily you want to process (the Mode parameter, with Subtle, Medium and Aggressive settings) and what general style of processing you require (the Preset parameter, with Broadband Clarity, Warm & Open, and Upfront Midrange options). Then you play your project and set the detection algorithm going, whereupon the interface partially greys out and you’re treated to tantalising glimpses of various parameters zipping around under their own steam in the background. After four to 10 seconds, out pops your freshly baked Neutron setting, comprising custom settings for the Equalizer and Exciter, both Compressor modules and the Neutrino processor. (The Transient module, curiously, is omitted.)

Perhaps predictably, Track Assistant’s launch publicity was met with a certain amount of dystopian twittering about AI taking over the world. I don’t, however, see Track Assistant putting any mix engineers out of a job, because it’s actually a lot less intelligent than it initially appears. What it doesn’t do is evaluate the setting of each individual processing parameter based on its analysis of the audio. Instead, it first decides which of the five Neutrino categories (see the ‘Neutrino Spectral Shaping’ box for details) best fits the audio, and cross-references that with each of the three-way Mode and Preset selections to pull a mostly preset template out of a 5x3x3 matrix. Only then does it further analyse the audio to refine a handful of individual parameters.

Track Assistant in action!So, for example, if you leave Track Assistant’s Mode and Preset at their respective default settings of Medium and Broadband Clarity, and feed Neutron some audio that it decides belongs in the ‘Drums/Percussive’ Neutrino category, the plug-in will apply the following pre-programmed processing template:

Track Assistant in action!So, for example, if you leave Track Assistant’s Mode and Preset at their respective default settings of Medium and Broadband Clarity, and feed Neutron some audio that it decides belongs in the ‘Drums/Percussive’ Neutrino category, the plug-in will apply the following pre-programmed processing template:

- A processing chain featuring Equalizer, Exciter, Compressor and Neutrino, in that order.

- In the Equalizer module: a 24dB/octave high-pass filter, a 2dB low-frequency shelving boost, and three proportional-Q peaking filters (from lowest to highest: -3dB at Q=4.0, -4dB at Q=1.8, and +2.5dB at Q=0.5).

- In the Exciter module: two-band ‘Retro’ processing with ‘Defined’ pre-emphasis setting, with band Drive settings of 6.0dB and 6.2dB and Blend settings of 33 and 36 percent.

- In the Compressor module: full-band soft-knee compression with 5:1 ratio, ‘Peak’ detection mode, 1.65ms attack, 592ms release, 75 percent wet/dry mix, and side-chain filters set at 140Hz and 12kHz.

- In the Neutrino section, the ‘Drums/Percussive’ mode with Detail and Amount sliders both at 50 percent.

Finally, Track Assistant then refines (where available in the template) EQ frequencies, Compressor and Exciter crossover frequencies, and Compressor and Dynamic EQ thresholds in response to the audio. As a result, every time you run the Track Assistant it’ll usually arrive at a slightly different processed outcome, but the underlying pre-programmed template remains identical unless the algorithm happens to decide on a different Neutrino category, or you yourself change Track Assistant’s Mode or Preset settings.

Measuring Assistance

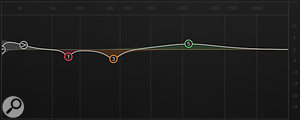

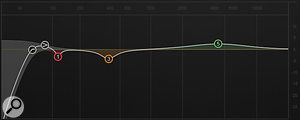

To help illustrate the extent of Track Assistant’s EQ customisation, here are three Equalizer curves created using its default ‘Broadband Clarity’ and ‘Medium’ settings. The three source sounds were, from top to bottom, an MPC-programmed distorted drum loop, a live drums bus, and a solo triangle percussion layer, all of which the algorithm assigned to Neutrino’s ‘Drums/Percussive’ category. Notice how the number of filters, the filter types, and the filter slopes remain unchanged, despite the big sonic differences between the source tracks. The only thing that does change is the filter frequencies.

To help illustrate the extent of Track Assistant’s EQ customisation, here are three Equalizer curves created using its default ‘Broadband Clarity’ and ‘Medium’ settings. The three source sounds were, from top to bottom, an MPC-programmed distorted drum loop, a live drums bus, and a solo triangle percussion layer, all of which the algorithm assigned to Neutrino’s ‘Drums/Percussive’ category. Notice how the number of filters, the filter types, and the filter slopes remain unchanged, despite the big sonic differences between the source tracks. The only thing that does change is the filter frequencies. So, Track Assistant is not exactly HAL 9000, but the crucial question is whether it is useful in practice. Does it make things sound better? Well, it’s easy to come away with that impression initially, because, by default, the plug-in’s Bypass button doesn’t gain-match the processed and unprocessed signals, and many of the templates seemed to make the processed sound louder. Even with the iZotope’s auto-gain function switched in (see the ‘Latency & Bypass Modes’ box for details) to minimise that source of bias, many of the templates also seemed to brighten the upper spectrum in some way, and brighter sounds also have a habit of sounding more impressive instinctively.

So, Track Assistant is not exactly HAL 9000, but the crucial question is whether it is useful in practice. Does it make things sound better? Well, it’s easy to come away with that impression initially, because, by default, the plug-in’s Bypass button doesn’t gain-match the processed and unprocessed signals, and many of the templates seemed to make the processed sound louder. Even with the iZotope’s auto-gain function switched in (see the ‘Latency & Bypass Modes’ box for details) to minimise that source of bias, many of the templates also seemed to brighten the upper spectrum in some way, and brighter sounds also have a habit of sounding more impressive instinctively.

Factoring out those things, though, I can’t say that I felt Track Assistant fared appreciably better than Neutron’s ordinary presets, as far as I was concerned. To return to the drums example above, it doesn’t matter what the kit actually sounds like, that particular combination of Mode and Preset will always slap on a 2.5dB high-mid-range boost. The only variable will be the exact frequency at which the boost will be applied. Similarly, the Compressor module will always compress with 1.65ms attack and 592ms release, and the Exciter will always add the same amount of ‘Retro’ harmonics, regardless of the source sound’s transient characteristics or timbre. Given that I could surf through five or 10 normal presets in the time it took to configure and run Track Assistant once, I actually found it quicker to arrive at a processed sound I liked that way.

But, of course, mixing isn’t just about finding sounds you like. It’s also about dealing with more technical balancing concerns and fitting tracks together with each other. In this realm Track Assistant has even less to offer, not just because so few of its parameter tweaks actually respond directly to your audio, but also because it doesn’t take account of anything else that’s going on in the mix. We’re always telling people not to apply mix processing with the solo button down, but in effect, that’s exactly what Track Assistant does! And even if it wasn’t, it still couldn’t know what’s important about a track as far as you, the engineer, are concerned, because that’s as much an artistic issue as a technical one. It won’t recognise that a resonance is making your upright bass line uneven; in fact, it may blithely put in a new EQ peak that makes it worse. It can’t know that you find the stick noise on the overheads too harsh, and that its suggested high-end EQ boost isn’t helping. And it’ll miss the excessive low mid-range on the piano because it’s not aware that you’re happy to sacrifice that spectral region to the rich-sounding strings.

But, of course, mixing isn’t just about finding sounds you like. It’s also about dealing with more technical balancing concerns and fitting tracks together with each other. In this realm Track Assistant has even less to offer, not just because so few of its parameter tweaks actually respond directly to your audio, but also because it doesn’t take account of anything else that’s going on in the mix. We’re always telling people not to apply mix processing with the solo button down, but in effect, that’s exactly what Track Assistant does! And even if it wasn’t, it still couldn’t know what’s important about a track as far as you, the engineer, are concerned, because that’s as much an artistic issue as a technical one. It won’t recognise that a resonance is making your upright bass line uneven; in fact, it may blithely put in a new EQ peak that makes it worse. It can’t know that you find the stick noise on the overheads too harsh, and that its suggested high-end EQ boost isn’t helping. And it’ll miss the excessive low mid-range on the piano because it’s not aware that you’re happy to sacrifice that spectral region to the rich-sounding strings.

To be fair to iZotope, they don’t claim that Track Assistant will mix your track for you, but in stating in Neutron’s documentation that “Track Assistant’s goal is not only to ‘do no harm’, but in fact to deliver a good-sounding, intelligent starting point” I still think they’re overselling it. It did plenty of harm to some of the tracks I fed through it, both aesthetically and from a mix perspective, and didn’t to my ears provide significantly more promising starting points for real-world mixing projects than normal presets — at least, nothing that outweighed the extra time the algorithm required to do its business. Furthermore, it worries me that novice engineers, who already tend to over-rely on presets, may take Track Assistant’s ‘intelligent’ suggestions rather too much at face value, and end up exploring a frustratingly large number of blind alleys at mixdown.

Neutron Star?

First and foremost, what appeals to me about Neutron as a package is the sheer sound-sculpting power of its core processing. Whenever I felt dissatisfied with the fundamental character of a track while mixing with this plug-in, a quick surf through the preset library immediately presented me with a bunch of radically different timbral possibilities to play with, and I was usually able to find something more subjectively engaging pretty swiftly — a process helped enormously by those all-pervasive wet/dry mix controls. Moreover, the flexibility with which Neutron allows you to snipe fiendishly complex mixing gremlins is commendable. The Masking Meter is a nicely implemented extra, and can be helpful at mixdown as long as you resist the temptation to start mixing with your eyes, though I don’t think it’s quite cool enough on its own to justify Neutron’s purchase price if you already feel your processing bases are covered by other plug-ins. And as for Track Assistant: at best, I found it scarcely more useful than static presets; at worst, it felt like a time-wasting red herring.

It might be those features that grab the headlines, but in practice, it’s the old-fashioned virtues of processing power, flexibility and sound quality that make Neutron useful. That it can excel both as a creative ‘box of colours’ and as a troubleshooting Swiss Army knife at this price makes it an attractive proposition for project studio work in particular.

Alternatives

An important part of Neutron’s appeal is the way its presets combine multiple processing types to generate a huge variety of distinctive tonal options. In this respect Toontrack’s EZ Mix could be seen as an entry-level alternative for those who want a much more straightforward (ie. almost non-existent!) control set. IK Multimedia’s T-RackS bundles are closer competitors, as I see it, giving a lot of tweakability of the individual blocks in any given processing chain, so you can tailor a promising-sounding preset in much more depth, as well as designing your own chains from scratch featuring a range of emulations of classic outboard hardware. In terms of precision troubleshooting, though, I reckon Neutron still has the edge. Melda’s MXXXCore plug-in, on the other hand, boasts even more routing and side-chaining flexibility than Neutron, but at the expense of a control glut that’s arguably even more intimidating.

If you’re primarily interested in Neutron for its Masking Meter, then you’ll not find anything directly comparable elsewhere, to my knowledge. There are, however, some spectrum analysers (such as Blue Cat Audio’s FreqAnalyst Multi or Schwa’s Schope) that offer the ability to compare spectral displays from different tracks, which is probably the next best thing.

What’s Masking?

The term ‘masking’ or ‘frequency masking’ refers to a psychoacoustic by-product of the way the human hearing system works. What it boils down to is that if you have a sound source in your mix which puts lots of energy into any particular part of the frequency spectrum, it’ll tend to obscure that spectral region of other sounds. So, for example, if you try to balance a load of heavily overdriven electric guitars against a natural-sounding grand piano, the dense upper-spectrum harmonics of the guitars will subjectively dull the piano tone by ‘masking’ its high frequencies, even if the instrument’s recorded timbre seems just fine when heard in isolation.

Neutrino Spectral Shaping

Once audio has made it past Neutron’s five main modules, it hits a special spectral-shaping section called Neutrino. Roughly speaking, this processor is something akin to 32 narrow bands of low-ratio dynamic EQ spread across the audible spectrum, their aim being to control narrow-band frequency peaks (which can lead to bass unevenness and high-frequency harshness, amongst other things) and even out the overall spectral balance of instruments, thereby improving the sense of detail. To use it, you first choose one of the four instrument-themed Neutrino Modes: Vocals/Dialogue, Guitar/Instrument, Bass or Drums/Percussive, and then adjust the character and strength of the processing with the Detail and Amount settings respectively. (An additional ‘Clean’ Neutrino Mode bypasses the spectral shaping altogether.)

In the documentation, iZotope explain that the Neutrino processing is a deliberately subtle effect, since it’s designed to achieve a cumulative result when applied across many different tracks in the mix. They’re not kidding, either. In fact it’s so subtle that when first trying out the Neutrino options on single tracks, I had to do a null test to convince myself they were actually doing anything at all! Even when I plumbed all the tracks in a couple of mixes through the Neutrino processing and then cranked all the knobs to the max, the result still seemed pretty subliminal. The most audible characteristic for me was a marginal ‘smoothing off’ of anything edgy in the sound. On the one hand, I liked how this benefited instruments with a tendency towards harshness (over-abrasive cymbals or electric guitars in particular), but on the other hand I did also notice some shrinking of the mix’s depth perspective (ie. closing the perceptual distance between foreground and background elements) and a slightly reduced sense of musical ‘excitement’, for want of a better description. As such, I found myself steering away from blanket applications of Neutrino, reserving it for tracks that specifically required a touch of anger management.

Neutrino is also available as a self-contained plug-in, which is a free download from the iZotope web site, so it’s easy to try it for yourself.

Latency & Bypass Modes

By default, Neutron operates in its True Bypass mode, such that hitting the plug-in’s Bypass button removes both its CPU load and processing latency from the chain, and this also works piecemeal if you bypass individual modules or switch their internal crossovers to zero-latency mode in the plug-in’s Options window (the latter at the expense of audio phase-linearity for multiband modules). In addition, there’s a dedicated Zero Latency button to the top right-hand side of the plug-in GUI, which completely avoids additional processing delays if you’re using Neutron in the recording or monitoring path while tracking. This is achieved without an appreciable increase in the plug-in’s CPU load by virtue of bypassing the Neutrino spectral-shaping and switching the limiter into its least processor-hungry ‘Hard’ mode.

You’ll have to switch True Bypass off, however, if you want to engage Neutron’s global Auto Gain function, which automatically matches loudness between processed and unprocessed audio when using the plug-in’s main Bypass button. Although many plug-in manufacturers now offer gain-matching routines, they usually take the form of a static gain offset to the processed signal. What iZotope do here is more involved, dynamically riding the ‘dry’ signal’s gain to match the level of the processed path. And it’s not just a small amount of gain-riding — one preset I tried rode the dry signal over a gain range of more than 10dB. For comparison purposes, I thought this worked great, as the gain-riding was fairly benign sonically and kept the loudness match pretty good despite the gain movements incurred by various processing modules. It does, however, mean that you need to remove Neutron completely from the chain (perhaps using the DAW’s bypass button rather than the plug-in’s own) if you want a truly unprocessed bypass signal. I also found it extremely tedious that the Auto Gain setting has been switched off within all the included global plug-in presets, when I’d rather it had been immune to preset selections — as, for example, is the True Bypass tick box adjacent to it in the Options window. And, while we’re on the subject of gain-matching, I noticed that the Exciter module appears to increase the signal level by almost 1dB even with its Drive and Blend sliders at zero, which rather undermines any objective evaluations of its subtler settings.

There’s another auto-gain function to be found in the dynamics module, this time a more traditional static-offset type applied to the processed signal and automatically adjusted in response to changes in your parameter settings. In other words, it allows you to experiment with different compression amounts without having to fiddle with the compressor’s make-up gain controls all the time.

The Output Limiter

Right at the end of Neutron’s processing chain is a limiter. It has three algorithms to choose from: IRC II, the most sophisticated, which sounds like it uses some kind of multiband scheme; IRC LL, a slightly less refined version of IRC II with much lower latency; and Hard, which seems to be a simple broadband process.

Right at the end of Neutron’s processing chain is a limiter. It has three algorithms to choose from: IRC II, the most sophisticated, which sounds like it uses some kind of multiband scheme; IRC LL, a slightly less refined version of IRC II with much lower latency; and Hard, which seems to be a simple broadband process.

Three numbered buttons to the left of the algorithm selection give different limiting characteristics in each case, and both the amount of gain reduction and the target output level are governed by a Ceiling parameter that is set via a little red handle superimposed on the main output meters.

In use I rather liked IRC II in particular, which sounded a bit cleaner when pushed hard than some designs I’ve used, and as such I’d be happy to use it on full mixes, not just individual channel processing.

Machine Learning

In addition to the Track Assistant, all Neutron modules have a little Learn button, which provides something similar to Track Assistant’s EQ/crossover-frequency detection in stand-alone form. As long as you start with a given module in its ‘flat’ state, this really is a ‘do no harm’ feature, as it won’t engage any processing that wasn’t already active. I’d say that the EQ detection is probably most useful, and did seem to identify some relevant mixing frequencies.

I also liked that it tended to focus on areas of the spectrum that were the most prominent, as that tends to encourage the kind of subtractive EQ approach that’s most often advisable at mixdown. It was at its best on unpitched sources, though, since it was heavily swayed by the spectral peaks of specific pitches in the few seconds of audio it analysed, and pitches often vary a great deal between different arrangement sections in a real musical context.

The crossover detection had a reasonable hit rate too, in terms of splitting the spectrum into useful chunks, although in reality it didn’t actually feel like much of a time-saver. Multiband processing is capable of such dramatic results, and is so application-specific, that I reckon it pays to experiment with crossovers manually as a matter of course.

Audio Examples

Download | 50 MB

Pros

- Serious tone-sculpting power with plenty of onboard presets.

- Excellent troubleshooting capabilities.

- Conservative CPU usage.

- Numerous wet/dry Mix controls make tailoring presets significantly quicker and easier.

- The Masking Meter speeds up finding and EQ’ing undesirable frequency clashes.

Cons

- Dynamic EQ bands lack ratio, attack and release controls.

- It’s a big step between seeing where masking’s occurring, and deciding what (if anything) to do about it.

- In practice, Track Assistant isn’t much more useful than normal presets, and is considerably slower to use.

Summary

Neutron’s audio processing impresses both creatively and technically, delivering solid value for money and CPU cycles. The Masking Meter is certainly a useful ancillary feature, but that’s more than I can honestly say of Track Assistant.

information

Neutron £155; Neutron Advanced £235. Prices include VAT.

Time+Space +44 (0)1837 55200

Neutron $249; Neutron Advanced $349.