This image started out as a picture of my face. After stretching, inverting, filtering and remapping the left and right channels to different harmonic scales, the result sounds as frightening as it looks. Well, it was Halloween!

This image started out as a picture of my face. After stretching, inverting, filtering and remapping the left and right channels to different harmonic scales, the result sounds as frightening as it looks. Well, it was Halloween!

Now in its third decade, MetaSynth is still a synthesizer like no other, and its companion sequencer Xx follows the same path...

MetaSynth has been an open secret in the music industry for nearly 25 years. It is famous for its Photoshop‑like tools, which allow you to paint with sound. You may have heard of some of its more famous users, like Aphex Twin, who turned a picture of his face into fascinating noise in a song called ‘Formula’, a B‑side to his 1999 single ‘Windowlicker’. It was also allegedly used to create the ‘bullet time’ sound effect in The Matrix movie. Over the years, MetaSynth has expanded its bag of tricks, and the latest version — alongside its Xx companion — boast multitracking, MIDI sequencing, mixing, and plenty more.

MetaSynth might be one of the hardest things I’ve ever had to describe. It is, in essence, a collection of tools used to create and manipulate sound. Other applications would fit that description — audio editors, synthesizers, samplers, and DAWs. MetaSynth shares elements of these and yet is nothing like them.

Welcome To The Metaverse

MetaSynth and Xx are separate applications available exclusively for the Macintosh platform. MetaSynth is a synthesizer, although it doesn’t behave or look like any synth you might have encountered before. Xx is a MIDI sequencer that can also play MetaSynth instruments.

MetaSynth’s main trick is its ability to turn images into sound. But it has several other specialities. These skills are known as ‘rooms’. A room is a tab on the interface dedicated to a particular working method, and there are six: Effects Room, Image Synth, Image Filter, Spectrum Synth, Sequencer and Montage Room.

Image Synth is the room for which MetaSynth is best known. Here, you can see a canvas on which you can use Photoshop‑like tools to draw and manipulate imagery. The vertical axis represents frequency whilst the horizontal axis is time. You can import any picture in this canvas: your face, a sunset, or perhaps the Sound On Sound logo (it made a sound like an enormous laser beam!). Each pixel will trigger an oscillator with brightness dictating amplitude and colour setting the stereo position.

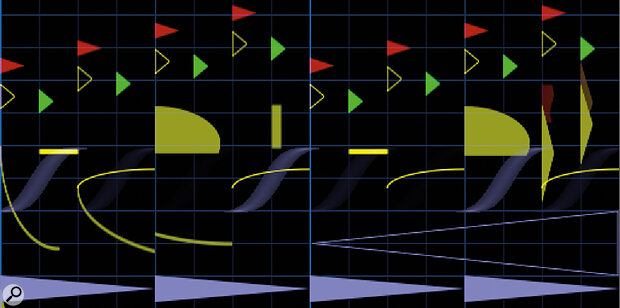

Programming drums in Image Synth can look a lot like a cubist masterpiece. Yellow colours are panned centre, red is left, green is right, and the blue drums are on another layer.

Programming drums in Image Synth can look a lot like a cubist masterpiece. Yellow colours are panned centre, red is left, green is right, and the blue drums are on another layer.

Importing pictures isn’t the only way to create sound. There is an impressive suite of image editing tools for drawing directly on the canvas or processing what is already there. For example, you might draw simple lines for a sustained note, then to cause the note to rise or fall in pitch, you might tilt the layer a few degrees (much like any image processing software, you work in layers to keep things manageable). Or you might draw a filled triangle using the shape tool, creating a drum‑like sound with harmonics tailing off as the play head moves towards the triangle’s point. You can spraypaint pixels, which sound like the audio equivalent of fairy dust, or draw in chord shapes and then smear them to create melodic drones. It is great fun and a surprisingly intuitive way to work with sound.

MetaSynth’s built‑in synthesizers generate the actual sound (the image itself is more like the sequencer). These are simple, efficient synths optimized for high voice count, as an image can create thousands of voices. There are five synths to choose from, and they cover most basic synthesis techniques, including wavetable, granular, FM, phase distortion, sample and multi‑sample playback. They generally consist of just an oscillator, perhaps an LFO and some simple effects. When dealing with such a high number of voices, you don’t need a super complex synth engine.

MetaSynth’s rooms are connected by an audio sample buffer. The top of the screen shows an audio waveform into which you can record audio, load from disk, or render audio from the current room. Think of it like a dentist’s waiting room. Your audio can sit in the waiting room, go into the dentist’s room to have work done, come back to the waiting room, and then visit the hygienist in a different room (trying not to bleed on the floor if possible). It’s the same set of teeth being worked on in different rooms.

Similarly, you can load in a WAV file, apply some effects in the Effects Room, render it back to the sample editor, and then transfer it to other rooms for further processing. Once you have a loop or sample that you like, you can render it to the current project sample pool (or WAVs on disk) to be sequenced in the Montage Room or used in other applications. The Montage Room can also use images from the Image Synth and Spectrum Synth or sequences from the Sequencer without rendering them first.

The Montage Room is where you can arrange audio files, images, sequences and audio tracks.

The Montage Room is where you can arrange audio files, images, sequences and audio tracks.

Returning to the Image Synth, there’s more to explore. For example, you can convert an audio file from the sample edit area into an image. This resynthesizes the audio allowing you to manipulate the image in fantastic ways. You can stretch it, blur it, tilt it, invert it, flip it, filter it, quantise it, or displace it. The options are dizzying. And because every pixel represents a specific frequency, you can even quantise it to a particular key and scale. Custom tunings are supported via Scala scale (scl) files, and a generous number are included by default.

The Image Synth is real time, meaning that changes you make can be heard immediately. There’s something satisfying about looping an image and hearing the loop change on every repeat as you add to, remove from, filter, and generally mess about with it. It is one of the principal ways to ‘play’ MetaSynth, and I’d advise finding a way to record the output because many golden moments can happen during an Image Synth session.

At this point, I’ll sneak in a complaint. It’s probably quite clear that MetaSynth is a playground for experimentation. It is baffling, therefore, that MetaSynth only has one level of undo. When many things you do are unpredictable, multiple levels of undo would seem like a must‑have. It feels like flying without a crash helmet. Thankfully, you can save as many images and render as much audio as you like. They will be stored in the current project, and you can reload them into the Image Synth or the Montage Room at any time. So, get in the habit of saving often.

A Tour Of The House

Let’s look at the other rooms. The Effects Room applies one of 25 different effects to the audio edit window. Effect parameters can be automated using a large envelope window with graphical tools to create complex envelope shapes. Once again, the results can be rendered back to the audio edit buffer or to disk. The effects range from the practical (volume, pan, and transpose), through classics (chorus, phasers, EQ), and into the weird and wonderful (time‑stretch, frequency shift, reshuffle, and granular).

Metasynth’s Effects Room allows you to apply effects and automate them using sophisticated drawing tools.

Metasynth’s Effects Room allows you to apply effects and automate them using sophisticated drawing tools.

The Image Filter room works similarly to the Image Synth. Instead of sequencing the oscillators, each pixel represents a stereo band‑pass filter. Pixel brightness represents gain, and colour affects the stereo spectrum. Like the Image Synth, you ‘play’ a picture from left to right, but unlike the Image Synth, there is no tempo. Instead, the picture is scaled to last as long as the sample in the sample editor. Again, like the Image Synth, you can save filter images to the current project, and MetaSynth comes bundled with some useful templates. These filter images can also be used in the Image Synth.

The next room is Spectrum Synth, another FFT analysis tool similar to Image Synth. You analyse the audio in the Sample Editor, creating a sequence of resynthesized additive steps that can be manipulated, reordered, reversed, transposed, stretched, scaled and mangled. You can apply formant envelopes, essentially imparting the formants of one sound onto another. It is a complex room to master, but experimentation will always yield something interesting. It’s almost like turning any sample into a liquid form where you can stretch, manipulate and separate every frequency. Turn vocal samples into percussion loops, apply vocal formants to acoustic instruments, or stretch a few notes into a giant evolving drone — it’s all possible in the Spectrum Synth.

Next up is the Sequencer. This room should be familiar to anyone who has ever used a piano roll. It’s not intended as a full sequencing environment (that would be Xx) but as a quick way to render phrases and riffs. There is no way to record MIDI into the Sequencer. Instead, you use tools to paint notes, chords and rhythms on to the canvas. Scale quantising keeps any bum notes out. The same internal synths found in the Image Synth are available as sound sources. In general, this means you’re sequencing simple oscillators or sample‑based sounds. The goal is to create a nice motif to render into the Sample Editor and then process in one of the other rooms. It may sound not very interesting, but many of the tools for manipulating notes on the piano roll mirror the image manipulation tools found in the other rooms. So you paint notes in, then stretch them across the canvas in various ways. It creates sequences you would never play on a piano keyboard.

The final tab is the Montage Room, a place to multitrack your samples and sequences. There are 24 tracks to play with, and mono or stereo events can be placed on any track. An event can be an audio file or a MetaSynth element, such as an Image Synth file, a Sequence or a Spectrum Synth graph. This means you can easily open an element in its respective editor room and tweak it a little. You can also record directly from your audio interface into any track. Whilst it may appear like a multitrack DAW, the Montage Room is quite basic. There is no plug‑in support, and although MetaSynth does offer effects, you can only apply one per track. There are no send or return channels, no master channel (although you can have one master effect), and no MIDI. You can mute tracks but not solo them. It wouldn’t be my choice of environment to make an entire song, but it’s useful for layering renders or sequencing a bunch of short loops to create a longer track.

Xx Rated

Xx is a MIDI sequencer that allows you to play MetaSynth instruments — those same instruments found in the Image Room and the Sequencer Room in MetaSynth. Additional features allow you to automate parameters via MIDI, which is not possible in MetaSynth. It doesn’t support audio tracks, but you can work around this using the Sampler and Multisampler instruments.

Tracks in Xx can sequence a single output. This can be one of MetaSynth’s instruments, a MIDI port, or an AU plug‑in. Xx blurs the boundaries of tracks by displaying all tracks’ data simultaneously in the piano roll, and you can select and edit data from multiple tracks at once. Each track has a different colour, and the notes in the piano roll are coloured accordingly. It’s an interesting approach that makes you focus on the song rather than one particular instrument. It can sometimes get confusing, but tracks can be hidden and locked to stop them from being edited by accident.

In Xx, tracks are colour‑coded so you can differentiate instruments. Showing all musical information at once can be helpful when composing.

In Xx, tracks are colour‑coded so you can differentiate instruments. Showing all musical information at once can be helpful when composing.

Much like MetaSynth, Xx makes use of Photoshop‑style tools for editing. You can draw in notes, like any piano roll, but tools like the Chord Pen, the Beat Pen, or the Pattern Painter allow you to treat the piano roll like a canvas, painting in often complex patterns with the swish of a brush. You specify a key and scale, and the tools are clever enough not to enter notes outside that scale. Transposing existing phrases or chords is intelligently handled too. Working in any scale, enter a simple triad chord, and transpose it up and down. The chord will adapt to be major, minor, diminished, etc, to fit the scale. It’s all rather clever. After you’ve painted your masterpiece, you’re free to go in and tweak individual notes’ lengths, velocities, pitches and so on.

There are too many tools to describe, so I’ll pick a couple of examples. The Pattern tool allows you to select from assorted patterns to paint into the piano roll. They might be drum patterns, musical motifs, or chord progressions. You can add your own simply by selecting notes from the piano roll and adding them to the pattern library. Again, patterns will automatically adapt to the scale of the song (although you can disable this for drum patterns), and the current grid settings will dictate the speed of the pattern as it is painted in.

The Multi Transform function is an excellent example of the kind of harmonic gymnastics Xx is capable of. Select a bunch of notes on the piano roll and open the Multi Transform function window. Here you can select up to four transform operations from transpose, invert, speed change, reverse, randomise, or constrain range. Some come with extra parameters to set. Then decide the number of repeats and press go. Multi Transform will repeat the selected notes and compute the necessary changes to pitch, velocity and time for each note according to the transform settings. It’s a great way to extend chord progressions or melody lines and will often produce interesting, although not always predictable, results.

Xx is an interesting sequencer. It seems limited at first, dealing only with piano roll notes, but its focus on intelligent tools and input methods sets it apart from other piano rolls. It is a constant theme across both MetaSynth and Xx — they focus on supplying unique and exciting tools to get the job done.

Xx’s Multi Transform function can create copies of a selection of notes whilst transforming on each repeat. Here it will transpose by seven semitones, reverse the timing (only every second repeat), randomise some notes (every other repeat), and then shift the octaves of the notes to sit within a certain range. It’s all very clever.

Xx’s Multi Transform function can create copies of a selection of notes whilst transforming on each repeat. Here it will transpose by seven semitones, reverse the timing (only every second repeat), randomise some notes (every other repeat), and then shift the octaves of the notes to sit within a certain range. It’s all very clever.

In Use

U&I promote MetaSynth and Xx as a pair. In reality, they’re quite different applications. It seems like Xx could have been another room in MetaSynth or perhaps just an extension to the Montage Room or Sequencer. I’m still unsure why it isn’t.

There are a great many tools that we simply don’t have time to explain. Whether you’re painting in arpeggio patterns into the Xx piano roll, or resynthesizing your own voice to a Pythagorean scale, the sheer number of functions on offer is both remarkable and daunting. Occasionally, some functions seem unnecessarily obtuse, like the snap‑to‑grid system, which doesn’t work in clock divisions (16ths, triplets...) but in ticks or pixels, depending on where you are. It would speed up workflow if MetaSynth were clever enough to convert these to more musical values.

The USP here is that both applications offer something genuinely unavailable elsewhere. MetaSynth is the star attraction, particularly the Image Synth, which is so much fun that it’s worth the price alone.

The USP here is that both applications offer something genuinely unavailable elsewhere. MetaSynth is the star attraction, particularly the Image Synth, which is so much fun that it’s worth the price alone. Importing random images is the party trick. But you quickly learn that painting with shapes, patterns and brushes can give astonishing results too. It’s incredible how simple triangles, squares and lines can produce something that sounds like a sophisticated drum machine. The spectral analysis and resynthesis are massively powerful too. Importing a vocal sample or a short piano performance, converting it to an image and then manipulating it can turn something bland into something mesmerising and often unrecognisable.

There does seem to be a ‘MetaSynth sound’. Image Synth often creates hundreds, if not thousands, of oscillators at once (try achieving that with MIDI!). It works best with simple waveforms, resulting in the sonic signature of additive synthesis. But how you arrive at those results means that MetaSynth can create sounds like nothing else. It is easy to see why it is such a popular tool for film and game designers. In particular, Image Synth seems excellent for sci‑fi, horror, futurism, electronic music, IDM, techno, or any genre that thrives on sounds never heard before.

Xx is quite a different thing. It excels at the creation of musical sequences by using unique tools and transformative functions that one would not find in the average DAW. This comparison to DAWs is interesting. MetaSynth and Xx are often referred to as a DAW, and I can see why, but that doesn’t feel entirely accurate. They are primarily sound‑design tools, or in the case of Xx, sequence design. You can use them to create complete songs (check out the many albums by MetaSynth designer Eric Wenger at www.ericwenger.bandcamp.com), but I suspect most users will want to use them to create interesting musical effects, phrases, and samples, which are then rendered and imported into Pro Tools, Live, Logic, Cubase and so on.

In Summary

There are a few niggles here and there. For example, both applications do not look good on my Retina Mac screen. The interface is littered with Photoshop‑like icons, which are small and pixelated. Thank goodness for the tooltips, which give you information on what each icon does as you hover over it. My other bugbear is the single level of undo, which afflicts both applications. I’m not sure why such a limitation exists, but I guarantee that you will lose something great sooner rather than later because you can’t return to it after experimenting.

As a reviewer, using MetaSynth might be one of the hardest things I’ve ever had to describe. It is, in essence, a collection of tools used to create and manipulate sound. Other applications would fit that description — audio editors, synthesizers, samplers, and DAWs. MetaSynth shares elements of these and yet is nothing like them. Because of this, you must forget what you know and prepare yourself for a steep learning curve. I will confess that this review took many months longer than it should have for this very reason. But it was worth it. MetaSynth and Xx will challenge how you think about creating music.

Pros

- Resynthesis, additive, wavetable, granular, FM, phase distortion, sequencing, sampling and effects — all as you’ve never seen them before.

- MetaSynth is a sound‑design powerhouse!

- Nothing else sounds like it.

- Xx is a fresh take on MIDI sequencing.

Cons

- The GUI could do with a refresh.

- Only one level of undo.

- Mac only (sorry PC users).

Summary

Unique is a word that is often overused. But in this case, it is absolutely justified. MetaSynth is a mature piece of software that is unmatched despite being around for 20-something years. If you are a sound designer and don’t mind a challenge, you owe it to yourself to check it out.