Microphones

You can’t have an open‑mic night without a microphone, and if you’re one of the few readers of Sound On Sound without one, you may find yourself paralysed by the bewildering choice on offer.

There are many excellent, affordable dynamic mics available at the moment, from companies like Sontronics, sE Electronics, Beyerdynamic and AKG. There are many excellent, affordable dynamic mics available at the moment, from companies like Sontronics, sE Electronics, Beyerdynamic and AKG. |

Beyerdynamic TG V50. Beyerdynamic TG V50. |

AKG D5. AKG D5. |

sE Electronics V-series. sE Electronics V-series. |

The classic for vocals is the Shure SM58, and despite being decades old, it’s still a very popular and perfectly viable choice. It’s a moving‑coil design — meaning it picks up sound using a diaphragm attached to a metal coil, which is suspended within a magnetic field — and while that’s hardly the latest technology, it has two major advantages: it’s extremely robust (as in, you can literally use it as a hammer in a pinch), and it doesn’t require phantom power. The latter point is pretty moot where modern mixers are concerned (all the mixers I listed earlier, both analogue and digital, supply phantom power), but the mic inputs on many PA speakers don’t provide the necessary power, so if your mixer dies and you need to plug straight into a speaker, you’ll be glad to have an SM58 or similar nearby.

If the idea of a dynamic mic appeals but you want something a bit more upmarket, check out the JZ HH1 or Austrian Audio’s phantom‑powered OD505. If the idea of a dynamic mic appeals but you want something a bit more upmarket, check out the JZ HH1 or Austrian Audio’s phantom‑powered OD505. |

Austrian Audio OD505. Austrian Audio OD505. |

There are many affordable alternatives — I’m a big fan of the AKG D5, Beyerdynamic’s TG V50 and V70, the Sontronics Solo, and sE Electronics’ V‑series vocal mics, to name a few, while slightly more upmarket models include JZ’S HH1 and the Austrian Audio OD505. All of those models sound great, are resistant to feedback, and are robust enough to take a knock or several (I speak from experience). With the exception of the Austrian Audio OD505, which is unusual in being an active dynamic mic, none of them require phantom power to work either.

Moving‑coil microphones do have some downsides though: they’re not generally very sensitive, which can be an issue if the preamps on your mixer don’t offer a lot of gain, and they also don’t tend to pick up very high frequencies that well. That’s not usually a problem in live sound (the ubiquity of the SM58 should reassure you there), but if you are concerned about those issues then you might want to choose a capacitor microphone for vocals.

Sennheiser e965.Capacitor mics use extremely thin and lightweight membranes to pick up sound, and are typically much more sensitive than moving‑coil mics, with better high‑frequency response and less off‑axis coloration. Their downsides are that they are often more susceptible to high‑frequency feedback, and that they’re more fragile than moving‑coil designs. However, if you want to elevate your vocal sound, there’s a huge number to choose from at a wide range of prices. Budget options include the AKG C5 and Rode’s M2, both of which are priced similarly to the SM58 but which will offer a noticeably more extended high‑frequency response and sense of ‘hi‑fi‑ness’.

Sennheiser e965.Capacitor mics use extremely thin and lightweight membranes to pick up sound, and are typically much more sensitive than moving‑coil mics, with better high‑frequency response and less off‑axis coloration. Their downsides are that they are often more susceptible to high‑frequency feedback, and that they’re more fragile than moving‑coil designs. However, if you want to elevate your vocal sound, there’s a huge number to choose from at a wide range of prices. Budget options include the AKG C5 and Rode’s M2, both of which are priced similarly to the SM58 but which will offer a noticeably more extended high‑frequency response and sense of ‘hi‑fi‑ness’.

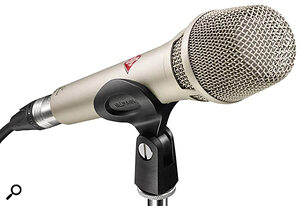

The cream of the crop of stage vocal capacitor mics come from names you’ll be familiar with if you’ve used many high‑end recording microphones. If your budget can stretch to them, it’d be worth considering models like the Austrian Audio OC707, DPA 2028, Shure KSM9, Sennheiser e965, Audix VX5 and VX10, Neumann KMS 105, Ehrlund EHR and Earthworks SR40V.

Of those, I’ve personally used the Audixes, the Neumann, the Ehrlund, and a very similar Earthworks mic (the Icon Pro) that employs the same capsule technology, and I can attest that they all sound fabulous — provided your PA is of a decent enough quality to let them shine.

DPA 2028. DPA 2028. |

Earthworks SR40V. Earthworks SR40V. |

Neumann KMS 105. Neumann KMS 105. |

I’ve focused on vocal microphones here, because for many (perhaps even most) acts, a single vocal mic will be all you need. Singing guitarists can DI their acoustic, while singing keyboardists can plug their electric pianos and whatnot into the line‑level inputs on your mixer. However, it’s in the nature of an open‑mic night to be unpredictable, and there will be times when an act turns up that confounds your expectations. You’ll need to be ready for anything, from beatboxing loop‑pedallists to accordions, pedal harps and hurdy‑gurdys, up to and including the Appalachian nose‑flute.

A small‑diaphragm capacitor mic will come in handy sooner rather than later! If you haven’t got a vocal capacitor mic to press into service, a studio ‘pencil’ mic such as this Aston Starlight should be able to deal with most acoustic instruments.I can’t tell you how to deal with everything that comes your way — though it’d be well worth reading Paul White’s recent ‘How To Mic Up Anything’ article — but I will say that, sooner or later, you’ll probably end up needing a small‑diaphragm capacitor mic or two. You may even have a pair already, but if you don’t, or if you’re (quite reasonably) reluctant to take your vintage KM84s to a beery environment, then don’t worry; you won’t need to spend much. Affordable models from the likes of Aston, Sontronics, sE Electronics, Rode, Lewitt Audio and more will serve you well, no matter what esoteric instrument crosses your path.

A small‑diaphragm capacitor mic will come in handy sooner rather than later! If you haven’t got a vocal capacitor mic to press into service, a studio ‘pencil’ mic such as this Aston Starlight should be able to deal with most acoustic instruments.I can’t tell you how to deal with everything that comes your way — though it’d be well worth reading Paul White’s recent ‘How To Mic Up Anything’ article — but I will say that, sooner or later, you’ll probably end up needing a small‑diaphragm capacitor mic or two. You may even have a pair already, but if you don’t, or if you’re (quite reasonably) reluctant to take your vintage KM84s to a beery environment, then don’t worry; you won’t need to spend much. Affordable models from the likes of Aston, Sontronics, sE Electronics, Rode, Lewitt Audio and more will serve you well, no matter what esoteric instrument crosses your path.

And if you go for one of the vocal capacitor mics I mentioned earlier, then you’ll already have a very capable instrument mic on hand — despite their ‘vocal mic’ shape, they are essentially the same sort of thing, based around the same kind of sensitive capsule that’ll get the best sound out of any acoustic instrument that doesn’t have an onboard pickup.

Finally, there are some excellent miniature instrument microphones around, which have a variety of instrument‑specific mounting options that will ensure the mic is in the optimum position while also eliminating the need to put up a bulky mic stand.

If you find yourself regularly dealing with a particular type of instrument, it may be worth investing in a miniature microphone with instrument‑specific mounting options, like Audio‑Technica’s ATM350a system.Audio‑Technica’s ATM350, DPA’s 4000 series, and Neumann’s new Miniature Clip Mic System are all available with a variety of mounting hardware to suit almost any acoustic instrument. They’re fancy mics, which means they’re not cheap, and you’ll need to specify the mounting accessories carefully, but if you’re running a folk‑oriented event, say, and you’re likely to see more than your share of fiddlers, then having an appropriate miking kit on hand could well be invaluable.

If you find yourself regularly dealing with a particular type of instrument, it may be worth investing in a miniature microphone with instrument‑specific mounting options, like Audio‑Technica’s ATM350a system.Audio‑Technica’s ATM350, DPA’s 4000 series, and Neumann’s new Miniature Clip Mic System are all available with a variety of mounting hardware to suit almost any acoustic instrument. They’re fancy mics, which means they’re not cheap, and you’ll need to specify the mounting accessories carefully, but if you’re running a folk‑oriented event, say, and you’re likely to see more than your share of fiddlers, then having an appropriate miking kit on hand could well be invaluable.

Accessories

That’s the big‑ticket stuff covered, then, but no less vital (if a little less glamorous) are the various sundries you’ll need to make everything run smoothly: that’s mic stands, cables, DI boxes, multi‑way mains extension boards, gaffer tape, adaptors and so on.

A cheap mic stand will do the job... but a well‑made one from K&M (or similar) will provide many years more service!There are two schools of thought where such ‘consumables’ are concerned. The first is that, since these odds‑and‑sods will spend their working lives being bundled into and hauled out of cupboards, car boots or beer cellars once or twice a week, there’s little point shelling out for top‑dollar stuff. The other is that the more you spend, the longer this kit will last. The latter is probably the wiser approach, but I must confess to cheaping out on things like mic stands, frankly because I’d rather spend the money on more exciting gear!

A cheap mic stand will do the job... but a well‑made one from K&M (or similar) will provide many years more service!There are two schools of thought where such ‘consumables’ are concerned. The first is that, since these odds‑and‑sods will spend their working lives being bundled into and hauled out of cupboards, car boots or beer cellars once or twice a week, there’s little point shelling out for top‑dollar stuff. The other is that the more you spend, the longer this kit will last. The latter is probably the wiser approach, but I must confess to cheaping out on things like mic stands, frankly because I’d rather spend the money on more exciting gear!

If you’ve finally got sick of the cheap plastic clutches on your mic stands breaking, though, you’ll probably want to solve the problem once and for all, in which case you won’t go wrong with K&M. As well as making excellent mic stands, they also do things like guitar stands, wheeled mixer racks, music stands, clips for attaching iPads to things, PA pole mounts, and pretty much anything else of the sort that you can think of.

Your DI box is going to spend its working life on a pub floor, so it’s worth getting something that’s built to last. Consider models from BSS, Radial or Whirlwind, for example.

Your DI box is going to spend its working life on a pub floor, so it’s worth getting something that’s built to last. Consider models from BSS, Radial or Whirlwind, for example.

Similarly, you can pay as little as £10 for a DI box, or you can pay £200 or more. With some premium models you’ll be paying extra for things like custom‑wound transformers and the saturation they provide, which may be more relevant for studio use than in a live‑sound environment, but in many cases a bigger budget will also buy you robustness and longevity — consider the classic chunky BSS models, or the hard‑as‑nails Radial DI boxes, for example. If those are beyond your budget, you might also consider offerings from Canford Audio, Orchid Electronics, or Whirlwind USA, all of whom make solid, reliable kit that should serve you well.

Similarly, you can pay as little as £10 for a DI box, or you can pay £200 or more. With some premium models you’ll be paying extra for things like custom‑wound transformers and the saturation they provide, which may be more relevant for studio use than in a live‑sound environment, but in many cases a bigger budget will also buy you robustness and longevity — consider the classic chunky BSS models, or the hard‑as‑nails Radial DI boxes, for example. If those are beyond your budget, you might also consider offerings from Canford Audio, Orchid Electronics, or Whirlwind USA, all of whom make solid, reliable kit that should serve you well.

Cables are a similar story, and unless you’re solder‑savvy you’ll be buying them off the peg. If you can, pay a little extra for cables that use branded connectors (Neutrik are the gold standard, but their sub‑brand REAN are decent, as are Switchcraft and Amphenol), as cheaper ones are more likely to fail, which can lead to intermittent connections, ear‑splitting crackles (especially where capacitor mics and phantom power are concerned), or just no signal at all. Brands like Mogami are a good, safe bet, as are Sommer Cable in Europe.

A couple of points while I’m on the subject of cables. First, get more than you need. Even the best cables fail sometimes, so spares are essential, plus you never know when a three‑piece band will gain a surprise new member who needs an extra XLR for his vocal mic, and another two for his accordion. Even without any musical ambushes, a few spare XLRs may get you out of a health & safety pickle in terms of laying your cables — they daisy‑chain, remember, so if your publican suddenly decides he needs the table you’ve set your mixing desk on and would you kindly move it right to the back of the pub, thank you very much, a handful of XLRs will be your friend. Finally, never underestimate the ability of guitarists to show up without a jack lead. A few instrument cables in the kit bag will pay for themselves in gratefully bought pints in no time at all.

A pair of closed‑back headphones can also come in handy for troubleshooting. Most mixers will allow you to route the solo or PFL bus to the headphones, meaning you can zero in on the source of that buzz or crackle without disrupting a performance.

Good‑quality cables, with connectors from reputable brands like Neutrik, will last much longer than cheap off‑brand ones.You’ll also need some means of powering your mixer, PA speakers, monitors and whatever backline your artists show up with. That last point is the wildcard, and why you should always allow for some extra power points: some artists come extremely well prepared, and may bring their own acoustic amp, pedal board, looper, laptop and more — all of which will need plugging in somewhere near the stage.

Good‑quality cables, with connectors from reputable brands like Neutrik, will last much longer than cheap off‑brand ones.You’ll also need some means of powering your mixer, PA speakers, monitors and whatever backline your artists show up with. That last point is the wildcard, and why you should always allow for some extra power points: some artists come extremely well prepared, and may bring their own acoustic amp, pedal board, looper, laptop and more — all of which will need plugging in somewhere near the stage.

Setting Up

So you’ve got all your kit, you’ve got a venue, and if you’ve got any sense you’ve turned up several hours in advance. The first problem you’ll need to solve is where to set up. If you’re lucky, an obvious ‘stage’ area will present itself, with power sockets nearby and an out‑of‑the‑way nook for you to park your mixer and pint. More likely, you’ll need to improvise, and that might mean rearranging a few tables, wheeling a pool table out of the way, or politely asking some punters if they’ll move while you set up the evening’s entertainment.

In any case, safety should always come first, so don’t block any fire exits, avoid cable trip hazards, and find somewhere for the performers to leave their instruments where they won’t get trodden on or tripped up over. Remember that your venue may well get much busier as the evening progresses, so leave plenty of space at the bar, and try to set up in such a way that the punters get a good view of the stage even if the place packs out.

Only after you’ve taken safety into account should you worry about niceties like putting your PA where it sounds best and provides good, even coverage of the venue. It may well be that the only safe place to set up is in the back corner of an L‑shaped bar, in which case you’ll just have to cope. If so, you may find it helpful to put a stage monitor part way round the corner, say, so that it does double duties as a foldback speaker and as a way of broadcasting to the rest of the venue. Or, if your venue is so small that you don’t have room for a stage monitor, you might have to get by with just one speaker serving both the artist and the audience.

Finally, once you’ve got your PA and mixer set up, a nice inviting vocal microphone set up on a stand in the middle of the stage with a coiled‑up jack lead for a guitar nearby will leave punters and performers in no doubt that, yes, this is the place with the open‑mic night, and yes, that’s where the stage is. It might seem a simple thing, but as a visual statement of intent it’s hard to beat, and novice performers will appreciate the fact that everything is set up and ready, so they don’t need to worry about anything other than performing.

Getting Organised

It’s beyond the scope of this article to go into too much detail about promoting your night, but suffice to say that the more people know that it’s happening, the more performers you’re likely to get. If this is your or the venue’s first such event, it’s definitely worth asking one or two musical friends to perform, and to schedule them as ‘headliners’ so that, even if no other performers show up, at least you’ll hear some music and the venture will still be worthwhile. Hopefully, after the first night, word will spread that there’s an open mic in town and you’ll get some takers for it the following week!

When you do start seeing apprehensive musical types poke their heads through the door, be sure to welcome them. It may well be their first live performance, and anything you can do to put them at ease will be greatly appreciated. Make a mental note of their names, ask them what sort of music they play, and if you’ve got a few artists wanting to play, consider their running order: it’s a safe bet that the guitarist in the patch‑covered leather jacket with the safety pin through his nose will be more raucous than the soft‑spoken folk singer with a mandolin, for example, and as a rule, louder = later.

Finally, remember to introduce your artists before they perform, and to thank them afterwards. They may be inexperienced and very nervous, and the more comfortable you can make them the better they’ll perform. Alternatively, they may be seasoned entertainers who raise the roof effortlessly, in which case you should absolutely invite them back and promise them the headline slot next time! In any case, being friendly counts for a lot. No‑one wants to play “that open mic night with the grouchy bastard”.

The fun and informal atmosphere of open‑mic nights makes them an ideal platform for first‑time performers, and also for novice sound engineers. All the skills you’ll learn will become invaluable if you ever move on to larger events — setting up PA systems and mics quickly, dealing with unfamiliar instruments, learning about speaker placement, fighting feedback... and, most importantly, meeting and working with musicians.

Money Money Money

It’s a sad fact of life that things cost money, and PA systems and microphones can cost rather a lot. Don’t remortgage your second‑born just yet though: you may be able to get some funding from your pub landlord or café proprietor. Impress on them that your efforts could provide their business with a serious clientele boost and they may be willing to invest, or even buy a sound system themselves, which, having read this article, you’ll be in a good position to help them with. It may also be useful to explain that a decent PA system and microphone will come in handy for other occasions, such as pub quizzes, raffles, charity auctions and so on.

On the subject of money, it’s not at all unreasonable to ask the bar owner for some cash for your trouble. Some may offer a flat rate; others may scale things such that if the bar takings exceed a certain amount, you’ll be paid extra — an arrangement that incentivises you to promote the event and attract more popular artists.

Finally, even though open‑mic artists don’t generally expect to get paid, without them there’d be no event at all, so anything you can give them, you should — even if it’s just a drink to say ‘thank you’ for turning up.

Battery Power

There are now quite a few battery‑powered ‘all in one’ PA/mixer options around, like this Yorkville EXM Mobile 8, which will let you take your sound outdoors without you having to worry about mains.

There are now quite a few battery‑powered ‘all in one’ PA/mixer options around, like this Yorkville EXM Mobile 8, which will let you take your sound outdoors without you having to worry about mains.

Mackie ThumpGO.There’s a growing number of PA speakers around that can run on battery power, and while that might not be a primary concern in a typical indoor venue, barbecue season is fast approaching. On a balmy midsummer evening you might find yourself very pleased to be able to set up in a beer garden rather than having to remain indoors. Systems like the JBL EON One Compact, Bose S1 Pro and Mackie’s ThumpGO each offer two microphone inputs plus mixing facilities, and can run for several hours on battery power alone.

Mackie ThumpGO.There’s a growing number of PA speakers around that can run on battery power, and while that might not be a primary concern in a typical indoor venue, barbecue season is fast approaching. On a balmy midsummer evening you might find yourself very pleased to be able to set up in a beer garden rather than having to remain indoors. Systems like the JBL EON One Compact, Bose S1 Pro and Mackie’s ThumpGO each offer two microphone inputs plus mixing facilities, and can run for several hours on battery power alone.

There are even some compact line‑array type systems around now that can work away from mains power, such as the HH Electronics Tensor‑GO reviewed elsewhere in this issue.

Health & Safety

Martindale EZ365.Most venues should have public liability insurance, which may cover you if an artist toasts themselves in an electrical mishap, but it’s still up to you to make sure that your own equipment is safe — and that may mean PAT testing it annually, and making risk assessments every time you set up your gear.

Martindale EZ365.Most venues should have public liability insurance, which may cover you if an artist toasts themselves in an electrical mishap, but it’s still up to you to make sure that your own equipment is safe — and that may mean PAT testing it annually, and making risk assessments every time you set up your gear.

Also, while it’s reasonable to expect that a venue’s mains power supply is safe, it’s absolutely worth making sure. For UK wall sockets, our Technical Editor Hugh Robjohns recommends the Martindale EZ365, which not only checks the presence of earth, but also the polarity and even the earth loop impedance of wall sockets.

Electrical safety in live‑sound environments is a hugely important topic — for more info, check out our 2005 article on the subject, which remains every bit as relevant today: www.soundonsound.com/sound-advice/power-electrical-safety-stage