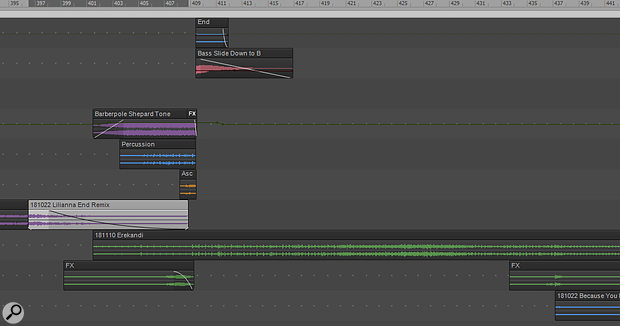

Several effects and additional parts were added to this transition, which ended up making a complete song that led into the next song (lower right track).

Several effects and additional parts were added to this transition, which ended up making a complete song that led into the next song (lower right track).

Cakewalk has all the tools you need to put together a seamless DJ‑style album.

DJ mixing is a pretty established art: you beat-match different tracks, crossfade them, sometimes pitch-shift them so you don't have jarringly untuned sections, add effects, and so on. But what if you're creating a project from scratch in Cakewalk?

My album project for 2018, Joie de Vivre (stream it from youtube.com/thecraiganderton) consisted of six individually recorded, rock-meets-EDM songs that I'd hoped to combine in a continuous mix. I figured I would just put the cuts and some transitions into Studio One's album assembly page, use the LUFS metering, add the needed crossfades and PQ codes, and be done. But when it was time to do the actual album assembly, I realised that there needed to be an intermediate step between finishing the songs and creating the final master: a little 'multitrack assembly' in Cakewalk.

As to the album's structure, the song tempos dictated the order, because I wanted the tempo to increase over the course of the album. (Rather than use the actual titles and take up space, I'll just number them.)

- 1. 115 bpm, key of A

- 2. 115 bpm, key of G

- 3. 118 bpm, key of G/D/G

- 4. 120 bpm, key of G

- 5. From 120-122 bpm, key of C

- 6. 122 bpm, key of C

- 7. 127 bpm, key of Am

Although the tempo differences between songs weren't huge, you can't get away with crossfading songs even a couple of bpm apart.

Crossfading

The first step was placing all the final mixes on the timeline. Because the songs had different tempos (and one had a tempo increase), it wasn't possible to assign a tempo to the timeline without constant tempo map re-tweaking. Any transitions created to 'glue' the songs together had to reference the songs, not the timeline. This required going back to the original songs, and essentially doing a remix for at least the beginning and/or end — for example, extending the cut, adding a new introduction, and/or ramping up a tempo change so a song could transition smoothly from one song to another.

Songs 1 and 2 had the same tempo, so they just needed a good crossfade. Song 1 had originally ended with a hard stop (no fade‑out) and spillover reverb, so there wasn't anything rhythmic to crossfade. I opened up 1 and extended the song by 20 measures, which meant grabbing bits of clips from the original song and creating a remix with tempo-sync'ed echo to add texture. I then extended 2's intro by remixing pieces of the song to create a new, eight‑measure intro, and crossfading to complete the transition. Harmonically, crossfading from the first song's tonic to its flattened seventh worked out well, because the music was sparse.

Tempo Matching

I cheated for the transition from song 2 to 3. There's a section toward the end of 2 with a long ritardando (for info on doing this in Cakewalk, go to craiganderton.com/tips.html and search for 'time trap'). Because the ritardando suspends a sense of timing, when the song came back, I upped the tempo to 118 bpm and extended the end to create a suitable transition into 3. A crossfade wasn't necessary; the end of 2 cut straight to the beginning of 3, and the common tempo made for a smooth switch.

The tempo transitions from 3 to 4 required creating two new files: a remix of the end of song 3, and a remix of the beginning of 4, so they could crossfade. The second file was sped up to create the necessary transition from 118 to 120 bpm, and because the clips were groove clips, they followed the tempo change.

Originally, song 6 was supposed to be song 5, and song 4 would transition into it, but the shift in tempo and style was too great. After numerous failed approaches, it proved simpler to create a separate piece of music that started at 120 and ended at 122 bpm. However, once in the timeline, that didn't quite work out either, because it needed embellishment — that's where assembling the album in a multitrack environment instead of a conventional two-track editor really made a difference.

Embellishing the transition to the new song 5 involved percussion, effects, an ascending series of pasted chords taken from song 4, and a clip of a Shepard Tone 'barber pole' effect (an aural illusion that sounds like a tone that's always rising). An ending cymbal crash and bass slide coincided with the start of song 5, and effects smoothed over the transition from 5 to 6. The end of 6 had a hard stop and a reverb tail, and one measure later, song 7 began at a slightly faster tempo. Because the tempo was interrupted, it was no problem to 'reset' it to a slightly faster tempo.

With the songs transitioning properly, the next step was bouncing these to a single, continuous WAV file. Then, for CD creation purposes, the file was split at every point where the disc would move onto a new track (and where Track Markers would eventually be inserted). After that, it was time to separate out each of these segments into its own track for processing and analysis.

All songs and embellishments have been bounced into a single, continuous file, which is split where CD track markers should go.

All songs and embellishments have been bounced into a single, continuous file, which is split where CD track markers should go.

LUFS Mastering & Level Balancing

LUFS (Loudness Units Full Scale) readings are the key to balancing the perceived loudness of the various cuts. If you're not familiar with the topic, look up Hugh Robjohns' detailed explanation from SOS February 2014: www.soundonsound.com/techniques/end-loudness-war.

Full disclosure: At this point in the project, I actually switched over to PreSonus Studio One's Project Page in order to take advantage of its analytics and publishing features, and used Waves' L3 Multimaximizer (one of my favourite plug-ins) to edit each song's perceived level. However, you can also do exactly the same kind of level balancing in Cakewalk, as I'll explain.

In order to do so, you'll need a metering plug-in that indicates a song's 'integrated' (more like an average, as opposed to instantaneous) LUFS reading after playing through a song. The Youlean Loudness Meter (https://youlean.co/youlean-loudness-meter/) is free and does an excellent job; you probably won't need the $47 pro version.

Insert a Sonitus Multiband plug-in followed by the Youlean meter in each song's FX Rack. The Sonitus Mulitiband can control the perceived level because it has a multiband limiter/maximiser feature. Leave the threshold for all the bands at 0, click the Limit button on the common page, and set the Out parameter for the desired amount of gain reduction (setting Out to 6dB, for example, provides 6dB of gain reduction). If you need to do any EQ tweaking, the ProChannel QuadCurve's Pure option is a great choice. Just make sure the ProChannel is placed before the FX Rack.

The Sonitus Multiband adjusts the perceived level, while the Youlean meter indicates the LUFS reading so you can even out song levels.

The Sonitus Multiband adjusts the perceived level, while the Youlean meter indicates the LUFS reading so you can even out song levels.

Play through a song to measure its LUFS level. Without any maximization, mine hit around -17 to -19. However, I wanted the sound a little more 'squashed' for CDs, and -11.4 LUFS sounded right. There's a correlation between dB and LUFS, so it was easy to Figure out how much gain reduction the Multiband needed to meet the target. For example, if the reading was -17.8 with the Multiband bypassed, then I needed about 6.4dB (17.8-11.4) of gain reduction. So, I set the Multiband's output control to 6.4 and got very close to -11.4, and sometimes hit it. Varying the Multiband output slightly can fine-tune the reading if needed.

Sonitus Multiband limits to 0.1dB, but this doesn't take 'true peaks' (intersample peaks in the reconstructed signal) into account. Youlean's metering shows if any true peak values exceed 0dBFS. Because you can't lower Multiband's output level, you have two choices. The first is not to worry about it, and just accept that some peaks may distort on playback. The other is to note by how much the file exceeds 0dBFS, and then reduce the level destructively by that amount before committing to creating a CD or digital stream.

There's one caution: LUFS readings are a huge improvement over VU or peak readings, but they're guides, not gods. Let your ears be the final judge when you use LUFS to help you balance your material. Although the songs on Joie de Vivre hit -11.4 LUFS, there's a transition that sounded right at -15.3, so I left it alone.

If you want to know whether this process works, listen to the album and see what you think. I believe you'll find that the song-to-song levels are perceived as equal — but it took a lot less time to get there than it would do using the usual methods. That's progress!