The Windows Media Center Edition will seek to support remote playback control devices such as the Turtle Beach Audiotron, via home media networking centred on the PC.

The Windows Media Center Edition will seek to support remote playback control devices such as the Turtle Beach Audiotron, via home media networking centred on the PC.

As I mentioned last month, the PC platform is going to change almost beyond recognition over the next few years. Not just in terms of pure speed, but in the way data moves around it, and gets into and out of it. Microsoft's socalled 'Longhorn' version of Windows, the biggest upgrade to Windows since the demise of Windows 3.11 (and the introduction of Windows 95) is some way off, but it will be the first operating system to use the new features due to arrive in our PCs any day now.

PC: People Centre?

One important aspect of Microsoft's roadmap is the intention to make the PC the centre of home entertainment. How people listen to music is important to musicians, not only because the more access we have to music, the more we listen to it, but because it's good to know how people will be listening to music in the future. And if you look just under the skin of this potential home media bliss you'll find technologies that will doubtless creep into music studios as well.

Information about the new Microsoft products is seeping out, but I thought it might be interesting to ask a few direct questions that are relevant to Sound On Sound readers. To this end, I managed to get hold of Tom Laemmel, who is Windows' Home Product Manager for Microsoft at their Redmond, USA site. Note that some of the answers Tom gave me are pretty technical, or refer to very specific technologies. There isn't room in this column to explain everything in detail, but please persevere, because there's some very important stuff here, especially about the new PC audio architecture.

We began by talking about Media Center (sic) Edition, the version of Windows XP that lets users control media playback and recording from a remote control. It's a lot slicker than it sounds and is already on sale in the US, where it has been well received. Difficulties with the way we do digital television in Europe have slowed down its introduction here, but it's certainly coming. I've tried it and it's certainly a great way to access your music collection.

Bluetooth Audio Developments

I recently had a call from the audio compression company APT, who have announced that they've teamed up with a Korean electronics firm to produce a chipset incorporating APT-X, their compression algorithm, with Bluetooth. What they are promising is extremely high-quality stereo audio over Bluetooth, at low cost.

APT-X is different from other compression schemes because it uses the more deterministic (and less destructive) ADPCM technique. Most other audio compression schemes use psychoacoustic assumptions to reduce the data rate. To grossly oversimplify, APT-X works by recording the numerical difference between adjacent samples. This has several advantages. There is little encoding delay, because there is no need to base the calculation on a large group of samples, and approximately 98 percent of the original data is preserved. What this means is that you can compress and uncompress audio, using APT-X, with very little degradation. (I'll discuss how and why in a future instalment of Cutting Edge.) The compression rate is only 4:1, but this is ideal for Bluetooth.

This could all be very significant for the audio industry. In fact, there's no 'could be' about it. What remains to be seen is how practical it is, and to what extent manufacturers in the hi-tech/audio arena pick up on it. I'm getting a sample board set sent to me by APT and I will be reporting back as soon as I've tried it out. I'll also talk about some possible applications of the technology, such as wireless loudspeakers.

Music & Home Networking

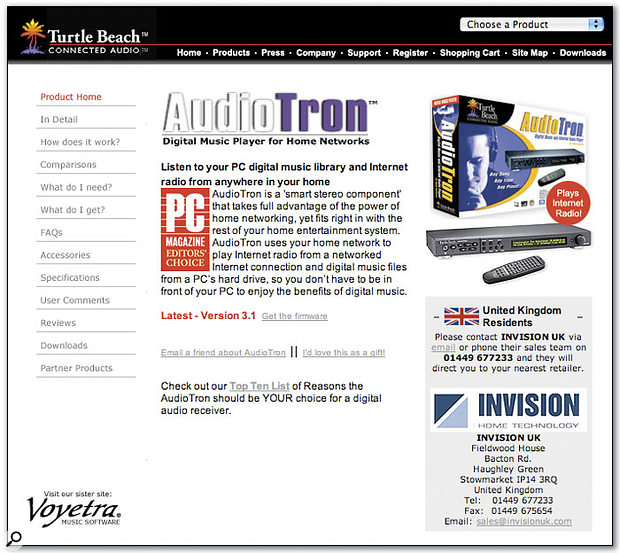

The first thing I asked Tom was whether the Windows Media Center Edition is going to be developed to include dedicated network playback clients. (For those not familiar with this term, an example of a media network client is the Turtle Beach Audiotron — see www.turtlebeach.com/site/products/audiotron/producthome.asp. Audiotron is a device that sits on a home network, wired or wireless, and lets you browse through your media collection remotely. It's equipped with digital and analogue audio outputs and behaves exactly as if it's another component in your hi-fi system.) He responded: "Our intention is to have the Windows platform (and MCE as part of that platform) support such networked devices through content directory services.

Tom Laemmel, Microsoft's Windows' Home Product Manager."Content directory services will help hardware manufacturers easily build devices that can access and play PC media files over home networks. That means that any song, photo or video you've collected can be seen or heard on TVs or other consumer electronic products connected to your PC. The vision is to make it possible for consumers to distribute media from the PC to nodes throughout the house (via Universal Plug-and-Play AV devices) — media anywhere, at any time, and on any device." Asked whether such networked media would only work with Windows Media, or would be 'format agnostic', Tom replied that Microsoft's goal would be "to support all the major audio and video formats".

Tom Laemmel, Microsoft's Windows' Home Product Manager."Content directory services will help hardware manufacturers easily build devices that can access and play PC media files over home networks. That means that any song, photo or video you've collected can be seen or heard on TVs or other consumer electronic products connected to your PC. The vision is to make it possible for consumers to distribute media from the PC to nodes throughout the house (via Universal Plug-and-Play AV devices) — media anywhere, at any time, and on any device." Asked whether such networked media would only work with Windows Media, or would be 'format agnostic', Tom replied that Microsoft's goal would be "to support all the major audio and video formats".

Bearing in mind that I was talking to Tom on behalf of hi-tech musicians, I then moved on to asking him how Digital Rights Management would work across a home network. Acknowledging that DRM over home networks "will be important in the future", Tom went on to say "we know that consumers want easy access to all of their content anywhere in the home, they want to 'do the right thing' (follow the law), and it's technology's job to make it easy to do so.

"Meanwhile, content owners will only be willing to participate with premium content if there are Digital Rights Management mechanisms to protect their content. Microsoft is currently investigating these challenges with rights holders, consumers, and partners in the PC and consumer electronics industries. We're working hard on solutions that respect the rights of content owners while delivering consumers a good-quality experience, but we're not ready to make any specific product announcements."

A Portable Protocol

My next question concerned the Media Transport Protocol (MTP), a powerful protocol allowing manufacturers of portable media players and jukeboxes to seamlessly interchange data with the PC. Tom explained that "there are three main industry benefits of MTP: simple device support, high performance, and flexible data handling.

"Simplicity is the biggest of these three. Today, device companies struggle with having to write drivers for different OS versions and having to provide custom synchronisation software. Users struggle with installing and learning special software before they can use their portable media devices. MTP removes these obstacles. Device companies don't have to write special drivers and software. Consumers just plug in an MTPcompatible device and it works.

"Performance is a close second. As the storage in portable media players becomes large, consumers will be carrying around thousands of audio, picture and video files. The MTP protocol is specifically designed to enable fast data transfer and metadata synchronisation of even very large file collections.

"The final benefit is flexible data handling. MTP supports a wide range of media files, but it can also support general object transfer for anything: for example, document files, contact information, calendar information... MTP is also designed to support a wide range of media playlist formats and a wide range of Digital Rights Management solutions."

No More Drivers Any More?

The acronyms kept coming thick and fast, as my next question to Tom concerned the relationship between the so-called Universal Audio Architecture (UAA) and Intel's Azalia [Find out more about Azalia in this month's PC Notes, starting on page 248]. Tom: "The Universal Audio Architecture is an initiative led by Microsoft that will provide hardware makers with built-in audio drivers for the first time, and eliminate the need for consumers to install additional software before plugging an audio peripheral into the PC.

"UAA drivers will be provided for three main hardware platforms: USB audio, 1394 audio, and system-integrated audio chipsets — an evolution of the current AC97 standard. Intel's Azalia specification is the UAA hardware platform for system-integrated audio. We have worked hard with our partners at Intel to open the controller, link and codec specifications to all industry partners so they can participate in UAA. Microsoft is adopting the Azalia specification as one of its UAA solutions, and will be providing drivers in Windows to support Azalia-compatible hardware."

My follow-on question concerned who will manufacture UAA products — Microsoft or others? And will Microsoft provide a reference design? Tom replied that "anyone can manufacture UAA-compliant hardware. Microsoft will not manufacture hardware. Microsoft will provide a reference design on how to build UAA compliant devices". He went on to point out that the documents concerning these plans are not yet finalised, underlining the fact that this really is breaking news. Indeed, I believe it is the first time much of the information here has been reported in Europe. There's a lot to digest, and you can be sure I'll be unravelling it in future Cutting Edge columns.

Digital vs Analogue: A New Twist

Arguments, or even opinions, about whether digital audio can ever be good as analogue have been a bit thin on the ground lately. Maybe everyone's just bored with the debate, or perhaps the universality of the highly questionable MP3 format makes CD-quality audio seem like a blessing.

However quiescent the debate, though, there are still some unanswered questions. For example, given a very good vinyl recording, and assuming that we can ignore all the hiss, crackle and pops, just how extreme does digital audio's resolution have to be before even vinyl fans agree that digital audio sounds as good?

Well, I don't have the answer, although I suspect we might have passed the point a long time ago, with 24-bit, high sample-rate recordings, and formats like Super Audio CD, which uses one-bit quantisation and a sample-rate in megahertz.

But I couldn't resist letting you know about a technique that is rapidly taking off in the digital video domain, one that adds weight to the proposition that, given enough grunt, digital audio can perceived to be in every way as good as analogue. The process in question is called Digital Intermediate or DI, and it's coming to a cinema near you soon. (In fact you may already have see the result of it, in Panic Room starring Jodie Foster.)

DI is the process of scanning, or digitising, a film at a very high resolution. Forget what you know about television pictures: films are scanned with a minimum of '2K', which refers to the number of horizontal pixels in the frame. (The exact figure is 2,048 x 1,556 pixels). The amount of data this results in is almost beyond comprehension, because each frame of the film produces 13 megabytes of data, and there are 24 frames per second. When you see a 2K film scan on a specially calibrated high-resolution TV monitor, the pictures are unbelievably good!

2K is fine for most purposes. When the digital video images are processed (normally for colour correction and to give the film a particular 'look') and put back to film, no one ever suspects that DI has been used. The only sense in which you could tell is if you made a comparison to the same film without DI.

But if you scan the film at 4K instead of 2K, the distance between the samples is less than the average diameter of film grain. Now, although film doesn't use pixels — which are normally defined as the smallest meaningful part of a digital image — film grain could be said to be an analogue equivalent. There is therefore little point in using any higher scanning resolution because scanning sub grain-size areas on the film won't add to the resolution of the picture. In other words, a 4K scan is pretty much all you'll ever need.

Of course, audio media tends not to exhibit grain. The closest analogy is perhaps particle size on analogue tape. But I think the film DI example lends weight to the notion that, in all but the most obscure contexts, digital really can be as good as analogue. If anyone completely disagrees with me on this, let me know. It really is a fascinating area for debate!