Like drum & bass and jungle before it, dubstep showcases the inventiveness of British urban music. We explain some of its fundamental production techniques, from 'wobbly' bass lines to half‑time drum programming.

New genres appear on an almost daily basis in electronic music, but few have had the impact of dubstep. From the grimy nightclubs of Croydon to mainstream radio airplay, via high‑profile endorsement from acts as disparate as Snoop Dogg and Radiohead, its meteoric rise is unrivalled. With roots in the predominantly London‑flavoured two‑step and grime scenes, where experimental garage remixes were often made with FL Studio, dubstep has evolved its own production values that have set new precedents for the treatment of low‑end frequencies.

Labels like Tempa and Hyperdub laid the foundations with artists such as Horsepower Productions, Kode9, Skream, Benga and Burial. Not to be outdone, Dub Police and Sub Soldiers exposed us to Caspa and Rusko, two of the scene's most popular international ambassadors; they play to a weekly global audience of thousands. Throw in Skream's platinum‑selling remix of La Roux's 'In For The Kill' and you've got yourself a new sonic phenomenon.

Technical

Dubstep's main characteristics lie in its rhythms, bass and dark sound, with heavy use of spatial atmospherics, low‑end frequencies and swing. Initially based around a garage‑influenced, two‑step kick and snare beat, the genre has evolved over the last few years, with an increasing number of tracks containing a half‑step rhythm. This has become the form of dubstep that most people will be familiar with, and it's a characteristic that distinguishes it from most other dance music.

Dubstep also has many similarities to drum & bass: both rely on the use of shuffled and syncopated hi‑hat patterns to give the beats movement, and heavy sub‑bass for warmth and depth. The tempo of dubstep is generally around the 140bpm mark, which provides potential for DJs to mix it with breakbeat, whilst an increasing number of drum & bass DJs are using dubstep in their sets too.

Although there are stylistic similarities between dubstep and drum & bass, the latter has suffered from stagnation in the past through the over-use of various techniques, samples and sounds. One of the most exciting elements of dubstep is the freedom to move away from a set song structure and the reliance on breaks and bass drops. Like most forms of electronic dance music, a lot of dubstep is created for the dancefloor and produced to be heard on a loud sound system. Because the music is typically driven by its sub‑bass, it can be hard to feel the full effect of dubstep on an inferior system such as computer speakers or earphones.

Wall Of Sound

A key feature of dubstep production is the use of atmospherics and textures to create a full and spacious mix. The use of silence, pads and minor keys builds tension and expresses emotion. Even though dubstep is dominated by bass and beats, they are softened by a dub reggae‑influenced use of echo, reverb and panoramic stereo to add depth and space.

Good examples of these techniques come from drum & bass‑turned‑dubstep duo Kryptic Minds and Mercury Prize nominee Burial, in particular the latter's use of obscure samples, pitch‑shifting and overlaying effects. Burial's work is very different to the majority of commercially successful and dancefloor‑friendly dubstep tracks, and bears a lot of similarities to works by Brian Eno or Philip Glass.

In my quest to decide what would fit best in an informative dubstep tutorial, I asked numerous producers, and there was a unanimous verdict: inform people that making dubstep is more than just automating a filter cutoff to make a 'wobbly' bass line. Although I will look at how to make the type of wobbly bass line that has become synonymous with the genre, you only have to investigate my recommended listening (see box) to hear the variety and contrast dubstep has to offer.

Kick & Sub

There is no set method to making dubstep. A lot of tracks are built around their dominant low‑frequency elements, namely the sub‑bass and kick drum. If you have chosen a sample or programmed a hook that you think you can be the basis of a dubstep track, by all means work from that first, but as there is an emphasis on the lower end of the sonic spectrum, it is essential that you select a kick and sub‑bass that gel together.

As in many electronic styles, drums are commonly created through overlaid samples. Try to merge contrasting sounds together when making your drum tracks, as the tendency to overlay similar‑sounding samples will have a negative effect on the sound. And don't be afraid of variety: try using hip‑hop or house kicks alongside more obviously dubstep‑friendly sounds. You could even use a pitched‑down basketball bouncing. If a more organic sound is what you're after, use live or ethnic drum samples. It's always best to have an abundance of decent drum samples available, as each individual kick, snare or hat sample can completely change the dynamic of your track, particularly the shuffle and swing aspect.

The use of single or multiple sine waves is a good starting point for making dubstep sub‑bass. There is no harmonic content in a straight sine wave, and the C0‑C1 octave range will produce a fundamental frequency sitting at approximately 30‑60Hz. When picking a kick drum sound, therefore, there is no point in choosing a really bassy 808 kick-drum sample, as it will not work well with such a sub‑bass. Instead, start with a kick drum that hits higher up the frequency spectrum than the sub-bass: that way, the two will not sound muddy in the mix. (You could, of course, use an 808 sample for your sub‑bass itself...)

Aside from selecting elements that match each other, there are several ways of making parts sit well together in the mix. One of the easiest methods is to use EQ to cut away unwanted frequency ranges. It's always better to take away frequencies than to boost them; if your drum sample is lacking low‑end presence, EQ can add it, but it will sound better if you use one that has that presence in the first place.

Something that has become quite popular in electronic dance music is the use of a side‑chained compressor to 'duck' the volume of the sub‑bass when the kick drum hits. This is a great way of making sure the kick cuts through in the mix, but it shouldn't be seen as the be‑all and end‑all, and there are certain techniques that can help it work better. One such is to duplicate the kick-drum track and use a closed hi‑hat sound instead of a kick-drum sample to trigger the compressor. A hi‑hat hit has a shorter tail than a kick drum, meaning that the resulting ducking will be shorter and not sound laboured. To make sure the hat isn't part of the mix, give it a dedicated channel and mute it from the master out.

Snares & Claps

Reverberated snare drums play heavily in dubstep's make‑up — take Skream's remix of 'In For The Kill' as an example. To obtain a typical dubstep snare drum, you need to layer a snare sample, or multiple snare drums, with a clap. A snare drum that punches in at around 200Hz is a good place to start; the clap will take care of the high end. Then, by using a reverb effect on the layered samples, you can add the space and width you need. There are no set parameters for layering snare drums or adding reverb: it's all about defining the sound you want to create. If you're interested in making club‑friendly dubstep, each aspect will need to be fine‑tuned and balanced so the mix will sound good on a loud sound system. If you're hoping to make more expressive or abstract dubstep, the freedom is all yours. You can choose to use anything you want as a drum sample, and innovation is good.

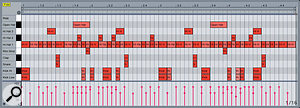

To illustrate dubstep programming, I've created some example patterns using a basic drum rack in Ableton Live. As you'll see, I'm using two kick drums — one low and one high — a snare, a clap, a rimshot, three closed hi‑hats, an open hi‑hat and a ride. These are labelled in the screenshots.

The first example, on the previous page, A basic half‑step rhythm, with 'lazy' off‑beat kick drums. The use of varying hi‑hat sounds and velocities adds movement. shows a pretty basic half‑step pattern, with 'lazy' off‑beat kick‑drum beats that increase the feeling of swing. The use of velocity on each sample is key to making the drums both swing and sound less quantised and robotic — note how the velocity changes on the 'lazy' kicks. Meanwhile, rimshots on the off‑beats add shuffle to the beat, while the contrast between open and several closed hi‑hat sounds adds movement and variety.

A basic half‑step rhythm, with 'lazy' off‑beat kick drums. The use of varying hi‑hat sounds and velocities adds movement. shows a pretty basic half‑step pattern, with 'lazy' off‑beat kick‑drum beats that increase the feeling of swing. The use of velocity on each sample is key to making the drums both swing and sound less quantised and robotic — note how the velocity changes on the 'lazy' kicks. Meanwhile, rimshots on the off‑beats add shuffle to the beat, while the contrast between open and several closed hi‑hat sounds adds movement and variety.

The second example, above, A slightly more complex, hip‑hop‑influenced pattern, again with 'lazy' kicks, rimshots on the offbeats and plenty of variety in the hi‑hats.shows another half‑step pattern, which is a bit more complex than the first, with something of a hip‑hop vibe. The introduction of an alternating hi‑hat riff increases the sense of a shuffle feel. Again, note the differing velocities.

A slightly more complex, hip‑hop‑influenced pattern, again with 'lazy' kicks, rimshots on the offbeats and plenty of variety in the hi‑hats.shows another half‑step pattern, which is a bit more complex than the first, with something of a hip‑hop vibe. The introduction of an alternating hi‑hat riff increases the sense of a shuffle feel. Again, note the differing velocities.

A sure‑fire way of adding swing to your beats is to create them in a triplet pattern. This can be done by using the same 4/4 time signature as you would normally do, but having the grid for your beats in divisions of three instead of four. A tool like Ableton's piano‑roll editor makes it easier to be precise in your placements. When using triplets, it's important to make sure that you build up patterns carefully, as misplaced elements are easily noticeable to the ear and do the complete opposite of adding swing!

In the basic triplet rhythm shown below A basic triplet rhythm., we have kicks on the first and fourth beat of the bar, with snare on the off‑beat and an additional kick two‑thirds of the way between the second and third beat, adding triplet feel. This is emphasised by the two sets of rimshots two‑thirds of a beat apart and the additional hi‑hat and ride elements.

A basic triplet rhythm., we have kicks on the first and fourth beat of the bar, with snare on the off‑beat and an additional kick two‑thirds of the way between the second and third beat, adding triplet feel. This is emphasised by the two sets of rimshots two‑thirds of a beat apart and the additional hi‑hat and ride elements.

The second triplet‑based rhythm has more of a two‑step feel A slightly more complex two‑step, triplet‑feel beat, punctuated by rimshots., and is based around a two‑bar loop with dropped kick on the second bar. Snares are placed on the second beat of each bar, and two‑thirds of the way between the third and fourth beat. Hi‑hats have a triplet pattern and rimshots are placed in between kicks and snares. Placement requires listening and fine tuning.

A slightly more complex two‑step, triplet‑feel beat, punctuated by rimshots., and is based around a two‑bar loop with dropped kick on the second bar. Snares are placed on the second beat of each bar, and two‑thirds of the way between the third and fourth beat. Hi‑hats have a triplet pattern and rimshots are placed in between kicks and snares. Placement requires listening and fine tuning.

Swing Time

In general, placement of hi‑hats is incredibly important to making your beats shuffle and swing. Unlike house or techno, dubstep uses a lot of placements on the off‑beat. Although this can feel unnatural to the ears, the combinations of hats and other percussion samples can be built up to create excellent beats. Slowly layering elements and making sure they work well with others can involve a lot of listening and time, particularly if you're using triplets.

Velocity is also incredibly important in making your beats sound more natural. Even though your beats might be heavily quantised, not only will changing the velocity help swing, it can take the edge off highly processed beats. You can also use classic drum breaks chopped up and layered in with your programmed beats. This technique is standard practice when making drum & bass, and it can help soften the sound and add movement.

Subsonic Bass

I mentioned that sine waves are a good starting point for creating a subby dubstep bass. Let's look at bass sounds and bass lines in a bit more detail. As a starting point, use a two‑oscillator synth to generate two sine waves an octave apart, and route both through a low‑pass filter. Turn the filter resonance up full and slowly move the cutoff anti-clockwise until you can detect a change in the feel of the bass coming from your speakers. Finding the right settings for the filter cutoff and resonance will trigger self‑oscillation, making the bass thicker.

If you want to add brightness to this bass, you can then distort it or add other effects. Guitar processing and effects plug‑ins are a great method of changing the sound of your bass and adding distortion, warmth and harmonic content. You can also add movement with an LFO. Applying a high‑pass filter to most other mix elements, such as leads and pads, will ensure plenty of space for your sub‑bass.

What, then, of the trademark dubstep 'wobble'? To create a good wobbly bass line, you need to start by setting up the oscillators on your synth. Most analogue‑style synths will have the basic three waveforms — saw, triangle and pulse/square — and probably some other spectrally interesting waveforms as well. Combining different waveforms allows you to create an endless array of sounds, so get to know your software and understand how it works. Native Instruments' Massive is a common tool for producers, but whatever bass software you use, spend time exploring it, saving each sound at various stages. You can return to them later to develop an idea or gain inspiration.

In the example Massive patch, left overleaf, A typical 'wobbly' bass patch in NI's Massive. I have used a selection of different waveforms, each of which provides a different aspect of the bass sound. Once you are happy with your waveform selections, route them all to the filter. A low‑pass filter is a good place to start, and by turning the filter cutoff knob clockwise, we increase the brightness of the sound. The application of an LFO to the cutoff will automate this effect, creating the infamous wobble. (In Massive, it's easy to apply the LFO, by dragging and dropping it onto the filter cutoff.) The LFO waveform I'm using in the example is a sine wave, which offers a smoother movement than saw or square waves.

A typical 'wobbly' bass patch in NI's Massive. I have used a selection of different waveforms, each of which provides a different aspect of the bass sound. Once you are happy with your waveform selections, route them all to the filter. A low‑pass filter is a good place to start, and by turning the filter cutoff knob clockwise, we increase the brightness of the sound. The application of an LFO to the cutoff will automate this effect, creating the infamous wobble. (In Massive, it's easy to apply the LFO, by dragging and dropping it onto the filter cutoff.) The LFO waveform I'm using in the example is a sine wave, which offers a smoother movement than saw or square waves.

Once you've done that, you can start fine-tuning the speed of the LFO. Synchronising the LFO speed to the track's tempo will often sound best, but you can get some great sounds by automating the speed of an unsynchronised LFO.

Low‑end Techniques

Many soft synths will let you use multiple voices for a unison‑style effect, which can radically change your bass line. Adding multiple voices and detuning them creates rawness, and is a technique that is used a lot in making the 'reese bass' commonly found in drum & bass. Another trick is to set the synth that's playing your bass line to monophonic mode, overlapping the notes in your MIDI sequence, and adding legato and portamento/glide. This can blend the sound together and give smoother‑sounding note transitions.

Instead of having one single bass line that sounds repetitive, it's also worth experimenting with creating more than one bass sound. Once you are happy with your bass hook, you can either chop up the MIDI sequence so that it plays alternating sounds, or bounce each bass line down to audio and slice them up that way. The variation this provides will help develop an almost story‑like quality, where one sound will ask a question and the other will answer.

I have only covered the basics of how to set up a bass patch, and there are many further avenues to explore. Modulating parameters on your synth, such as the waveform, pitch and filter resonance, can dramatically change the sound, while the addition of a phaser, reverb, stereo widener or delay can alter its sense of space and movement.

The techniques I've mentioned regarding the sound design of your bass lines can also be developed further with the use of layering and resampling. Taking the time to build multiple layers of sound and then playing them back from a sampler is a good way of creating something different.

For the example in the screenshots below Layering sounds using a sampler. Here, I've created three variants on a bass sound using NI's Massive, and rendered each of them as an audio file (above right). Next, I've loaded all three into Kontakt (right) to use as a single instrument.

Layering sounds using a sampler. Here, I've created three variants on a bass sound using NI's Massive, and rendered each of them as an audio file (above right). Next, I've loaded all three into Kontakt (right) to use as a single instrument.  , I created three patches using Massive. Each of these is set up using different settings: one static, one detuned and one with a subtle LFO. For this method, I have not created a MIDI sequence; instead, I've programmed a single eight‑bar note at C3 for each. Once happy with the combination of these sounds, I bounce the eight bars as audio and load up my sampler — in this case, NI's Kontakt. Using Kontakt's wave editor and mapping screens, I've mapped the audio I created to the MIDI keys using the original root note C3. Now when I program a MIDI sequence for Kontakt, it will play the bounced combination of the three original sounds, and because of Kontakt's time‑stretching capabilities, the audio won't sound distorted when playing notes further up or down the scale.

, I created three patches using Massive. Each of these is set up using different settings: one static, one detuned and one with a subtle LFO. For this method, I have not created a MIDI sequence; instead, I've programmed a single eight‑bar note at C3 for each. Once happy with the combination of these sounds, I bounce the eight bars as audio and load up my sampler — in this case, NI's Kontakt. Using Kontakt's wave editor and mapping screens, I've mapped the audio I created to the MIDI keys using the original root note C3. Now when I program a MIDI sequence for Kontakt, it will play the bounced combination of the three original sounds, and because of Kontakt's time‑stretching capabilities, the audio won't sound distorted when playing notes further up or down the scale.

Pads & Leads

Your choice of lead sound can play a vital role in your music. Filling the frequency ranges throughout your mix is important, so with the sub, kick and snare taking up the low end, the 200‑800Hz mid‑range is a good area for your leads to sit. An extremely wide, stereo‑intensive sound won't be direct enough — leave the width for your pads and effects.

Creating a riff or rhythm with your hi‑hats allows you to work well with your leads and mid‑range bass lines later in the track. If you apply a similar rhythm to the MIDI sequence of your lead, it will work well with the overall swing of the track. Alternatively, adding a contrasting rhythm to your lead will help provide the feeling of a shuffle. Playing one sound off another will also help the narrative element of your track. As with Massive, most synths will have a wealth of presets to gain ideas from. Choosing complementary sounds when balancing your leads and bass lines is important. You can apply the same techniques for leads as for bass lines, such as detuning, glides and automating filter cutoffs.

Pads should have plenty of stereo width and movement, so layering extra sounds and adding reverb and delay prior to bouncing the audio will help. You can even process the sound further with more effects or time‑stretching, before bouncing to audio again and reworking the sound. As well as layered audio, you can use a sampler for manipulating vocal cuts or your own recordings in a similar fashion. You can also experiment with reverb and delay as auxiliary (send) effects. As the name suggests, dubstep takes influences from dub reggae, notably the heavy use of delay and reverb. Here's a typical dub delay effects chain in Live.

As the name suggests, dubstep takes influences from dub reggae, notably the heavy use of delay and reverb. Here's a typical dub delay effects chain in Live.

The Shock Of The New

Ultimately, there is no set method for making dubstep, because dubstep is a freeform artistic style, and this encourages a lot of people to try their hand at making it. The techniques I've explained in this article should open up some of the most commonly used effects, and hopefully offer some help to people interested in producing this kind of music. The thriving dubstep community tends to welcome innovation and fresh ideas, and it's this openness that continues to propel the music forward.

Recommended Listening

- Caspa & Rusko: FabricLive 37 (Fabric)

- Benga: Diary Of An Afro Warrior (Tempa)

- Burial: Untrue (Hyperdub)

- Caspa: Everybody's Talking, Nobody's Listening (Fabric)

- Emalkay: 'When I Look At You'/'Angie Got Stoned' (Dub Police)

- Kryptic Minds: One Of Us (Swamp 81)

- Excision: 'Yin Yang' (EX7)

- Kode 9 & Spaceape: Memories Of The Future (Hyperdub)

- Skream: Skream! (Tempa)

- Mala: 'Left Leg Out'/'Blue Notez' (DMZ)

- Digital Mystikz: 'Haunted'/'Anti War Dub' (DMZ)

- Boxcutter: Glyphic (Planet Mu)

- Various: 5 Years Of Hyperdub (Hyperdub)

- N‑Type: Dubstep Allstars Vol. 05 (Tempa)

Tips From The Pros

For some professional advice, I tracked down some of the UK's leading dubstep DJs and producers, including Birmingham dubstep DJ/producer Emalkay, creator of dancefloor smashes 'When I Look At You' and 'Mecha'; Cooly G, DJ and producer of Narst/Love Dub (Hyperdub); Ikonika, DJ and producer on Hyperdub who has recently released her debut LP Contact, Love, Want, Have; and dubstep production trio LV.

When you start making a track, are there any elements you naturally work on first?

Emalkay: "If I've already got a good idea in mind like a bass line or catchy riff, I'll lay that down first. Otherwise I tend to start with the beats.”

Ikonika: "I usually start with the melodies, record and write them all out. The chords are usually next, then everything else after.”

LV: "Things tend to come together in clumps. Say, a bass lick and a drum idea that go well together, or a couple of chords and some notes.”

Do you have advice for programming beats and creating swing/groove?

Emalkay: "I've been into swing and syncopation big time lately. The way I go about it is to make it sound as natural as possible if I'm using sampled instruments, so I'll throw a bit of randomisation in there, and make sure I nudge the notes between the eights manually so it doesn't sound wooden.”

Ikonika: "I try not to clutter my beats with too many sounds and hits. To get the right groove I just play them out on my keyboard and quantise when I need to. I like adding distortion and delays to my hi‑hats to get them swinging right.”

LV: "Trust your ears and try not to get bogged down in endless OCD hyper‑editing, quantising, fiddling.”

What's your number one tip for making great bass lines?

Emalkay: "I love tube distortion and clipping on any sort of bass line, even the sub if I have to.”

Ikonika: "Add some modulation — maybe a little flanger — that just gives your bass lines a silky movement. Keep it simple.”

How do you create space and depth in your mixes?

Emalkay: "A good amount of space between the frequencies works well (ie. rolling off muddy low frequencies on some things) and going easy on the reverb works well for me too.”

Cooly G: "When I mix it's all by ear and has got to sound right, which then has that space and depth naturally.”