Technical Integration

Game producers use a game development ‘engine’ of some sort to create and manage all gameplay and assets. Many options are available, but the most popular are probably Unity (used for this project), Unreal Engine and CryEngine. Developers either choose to manage sound assets directly within the game engine, or employ a ‘middleware’ audio management solution such as FMOD or WWise to do this. These are powerful sound effects and music integration tools for video games needing adaptive audio. They allow developers, sound designers and composers to import and manipulate audio files as part of the development process. Think of them as collaborative and highly specialised DAWs that are integrated with the chosen game development engine and platform. Middleware lets you apply specially designed audio plug‑in effects, mix in real time in response to game events, manage sonic assets, assign audio to game states, build immersive soundscapes and much more. It is most widely used on larger projects with clear scripting for sound and music events.

Setting up a small, self‑contained selection of equipment helped to give the music a distinctive character.Technically and creatively, the Chasing Static brief was quite open. Nathan and Headware were keen to review soundtrack evolutions as the game development progressed, rather than be too prescriptive about development engine or middleware. They wanted a bank of longish, evolving, cinematic‑styled pieces with clear sections that could be faded in or out, looped or arranged to suit the mood as needed. We agreed the game would need at least 10 evolving atmospheric soundscapes and three or four signature tracks for key game moments.

Setting up a small, self‑contained selection of equipment helped to give the music a distinctive character.Technically and creatively, the Chasing Static brief was quite open. Nathan and Headware were keen to review soundtrack evolutions as the game development progressed, rather than be too prescriptive about development engine or middleware. They wanted a bank of longish, evolving, cinematic‑styled pieces with clear sections that could be faded in or out, looped or arranged to suit the mood as needed. We agreed the game would need at least 10 evolving atmospheric soundscapes and three or four signature tracks for key game moments.

Unusually, timescales allowed me to put together some early sonic sketches and rough ideas, with the emphasis on them being throwaways of potential approaches. This gave me an opportunity to experiment with options and see which best fitted the creative vision. This also helped them check how the pieces might fit with sound‑design events right from the off. Feedback from these sketches set the tone for the final pieces and allowed me to try combinations of synths, sound sources and software tools such as reverbs and spatial processors.

A Sound Palette

By this point I’d reached a good understanding of the plot, style and atmosphere of the game, and got some useful feedback from early ideas. It was time to further imagine the sonic environments and world being portrayed. The big question was how to bring such concepts to life in sound, and I decided to assemble a specific selection of gear that was capable of delivering the right ingredients.

Both game and soundtrack were strongly influenced by ’90s games, hence the use of vintage MIDI modules.

Both game and soundtrack were strongly influenced by ’90s games, hence the use of vintage MIDI modules.

At the heart of this palette was an assembly of vintage and more recent synths: a Vermona PerFOURmer MkII, Yamaha TG33 and Reface CP, Roland M‑VS1 and M‑SE1 and Arturia Microfreak, plus Modartt’s Pianoteq soft synth. To lift things beyond the norm, I also dug out an old field recorder, a shortwave radio and a SOMA Labs Ether: a kind of anti‑radio that receives electrical interference that a traditional radio tries to eliminate. My idea was to capture the hidden sounds and atmospheres of the urban environment and radio waves surrounding us. Impressed with the Ether, I also purchased a SOMA Lyra8 to add to the ‘mad sonic science’ vibe.

SOMA’s Lyra8 and Ether contributed strongly to the ‘Radiophonic’ vibe.

SOMA’s Lyra8 and Ether contributed strongly to the ‘Radiophonic’ vibe.

Now I was ready to blend traditional synthesis with the secret sauce of field and ‘Radiophonic’ recordings, and also to sneak in the distinctly nuclear‑sounding tones of the Lyra8. All it then needed were some idiosyncratic reverb and esoteric sound‑sculpting options. NI’s Raum and AudioThing’s Wires became my secret weapons of choice for this. It started to feel as though things were hitting the spot, so I sent some quick sonic sketches to Nathan who got back excitedly to confirm that yes, these were the exact sounds and atmosphere he was after.

AudioThing’s Wires and NI’s Raum were heavily employed at the mix for their lo‑fi colour.

AudioThing’s Wires and NI’s Raum were heavily employed at the mix for their lo‑fi colour.

Composing The Soundtrack

I knew some dystopian ‘Radiophonic’ soundscapes to support gameplay environments were needed. I also knew what musical set pieces would be used for key stages within the game. In keeping with the previous process, I shared early examples with Nathan for these before committing to full compositions. Not being tempted to finish too early was key to getting to the right places musically and sonically, and it kept everyone fully involved.

Right from the off, I made a point of not being too concerned if ‘radioactive masterpiece #9’ or similar was rejected. In my mind, Nathan had the vision for his game, much like a film director does. I’d send over a short theme or sound snippet with a ‘How’s this?’ and quickly learned that “amazing... awesome.... beautiful” was not necessarily the response that was needed. “Perfect for the forest exploration scene...”, on the other hand, was. My advice here is to work collaboratively with your developers. Listen to them and adapt accordingly.

My advice here is to work collaboratively with your developers. Listen to them and adapt accordingly.

Alongside a collaborative and musically fluid approach, I made a point of offering thematic variants of each candidate track. These were easily rendered ambient or spatially differing treatments of arrangements, which gave Nathan extra freedom to use the compositions in different ways. In the event, he actually preferred some of the more leftfield alternatives. All the tracks were also arranged to include identifiable sections that could be easily edited, faded or looped to suit game events.

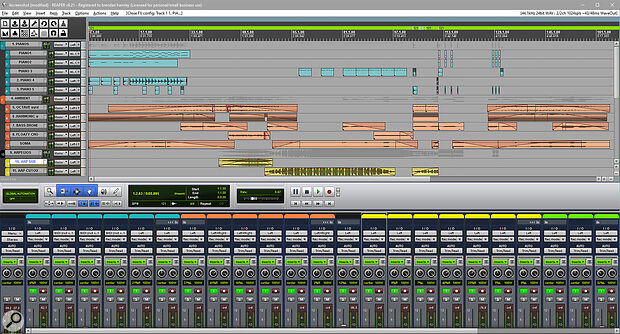

A typical Chasing Static mix in Reaper. For each cue, multiple variants were generated, emphasising different elements and atmospheres.

A typical Chasing Static mix in Reaper. For each cue, multiple variants were generated, emphasising different elements and atmospheres.

Reviews & Delivery

After I’d delivered a wide variety of music and soundscapes, it was time to pin my brother down and find out exactly which pieces were going to be used, so I could move on to final mixing and production. We’d been fairly loose about reviews and timescales up to this point, but as the game neared completion, it became important to agree some processes and nail final requirements. It’s worth understanding here that indie developers are normally buried deep in artwork, coding and solving technical issues, as well as networking and promoting their games. Nathan was no exception and I had to be fairly insistent at this stage, because I needed to know exactly what he needed and by when.

We employed Google Drive for feedback, iterations and sign‑off, using a consistent folder structure: Ideas (early versions), Candidates (full tracks for review) and Approved (completed tracks). This offered a clear framework, and the ability to track what eventually became more than two hours of music. This proved very helpful because in some cases earlier versions in the Ideas folder were preferred.

As the project had evolved over time, there were generally several iterations of each track. It was important to keep on top of these and make clear which versions were which. We used a filename schema loosely based on traditional software and document versioning to help keep things organised, so that we were always clear on the final list of track versions to be mixed and mastered.

Mixing & Mastering

The audio fidelity of the Chasing Static soundtrack was important, but it was equally important to match it to the listening experience of players. Monitoring was deliberately done using gaming and reference headphones, as well as consumer‑grade desktop speakers. I knew that Nathan, his testers and most players would be hearing the soundtrack the same way. Obviously, this goes against the grain of mixing and monitoring best practice, but it felt critical to get all the sonics aligned with the game experience.

Monitoring was deliberately done using gaming and reference headphones, as well as consumer‑grade desktop speakers.

Pre‑mastering, Adobe Audition was used to clean up any frequencies that might clash with the game’s sound design. In a similar fashion, its 3D reverb and spatialisation tools were useful in matching music to scenes involving differing acoustic spaces.

I’d been borrowing the ears of producer pal Jon Buckett from Earthworm Studios for feedback throughout the project, and asked him to spend a couple of days mastering the tracks. Jon, who was already familiar with the vibe, was quick to massage any frequencies or audio spikes that needed sorting out. We then set the tracks to consistent loudness levels. There’s much debate about this, but for gaming, ‑23 LUFS is the standard recommended by Sony’s Audio Standards Working Group.

Finishing The Game

In the end, I produced 23 pieces ranging from distinct musical compositions and evolving ambient pieces to drone‑type atmospheres. The soundtrack turned out to be a good listen in its own right, but placed within the game, it took off in directions I could never have imagined!

About Chasing Static

A psychological horror story, Headware’s game invites you to explore the wilderness of rural Wales, uncover the remains of a mysterious facility and find the truth behind the missing villagers of Hearth.

A psychological horror story, Headware’s game invites you to explore the wilderness of rural Wales, uncover the remains of a mysterious facility and find the truth behind the missing villagers of Hearth.

It will be out in the third quarter of 2021 for Xbox Series X|S, PS5, Switch, PS4, Xbox One and PC.