Burna Boy’s second album Twice As Tall saw his brand of Afro‑fusion top the charts all over the world. Jesse Ray Ernster tells us the remarkable story of how it was mixed.

Since arriving in Los Angeles as a complete unknown in 2017, Jesse Ray Ernster has wasted no time in heading to the top. Earlier this year he earned two Grammy Awards, one for Best Contemporary Christian Music Album for his work as an engineer on Kanye West’s Jesus Is King, and a Best Global Music Album Grammy for mixing Burna Boy’s Twice As Tall LP. Both albums went to number one on dozens of charts around world, in the case of Twice As Tall, in as many as 50 countries.

Ernster’s achievements in just four years are pretty impressive. He was born in Winnipeg, Canada, and grew up in Minneapolis, where he cut his teeth at home working in his producer dad’s studio, and playing in local bands. He also taught engineering and mixing at the Minneapolis Media Institute. When it closed, his wife and he moved to LA. Met with complete indifference, Ernster decided to take the high road to self‑promotion: “I applied with every studio and every producer, but no‑one was hiring. So I got this wild idea of delivering pink boxes of doughnuts with a really colourful, hideous‑looking resumé, to every studio in the Valley. I knocked on every door, and got laughed at in many places. But in the end I got hired by NRG in North Hollywood, and learned about LA session workflow, and also about unpaid work and cleaning toilets and mopping floors.

“Through connections I got a gig engineering for Tyga. One fateful evening Kanye West walked in, just to hang out. As he left, I told him that I’d love to work for him. The next day his management flew me to Chicago where he was working, and after that we went to Uganda to record in the middle of a safari resort, next to the Nile river. I could see hippos and giraffes in the distance while tracking vocals!”

Moving On Up

After this dream‑come‑true experience, Ernster signed with Bad Habit management, and as luck would have it, his manager also acts as A&R for Burna Boy. The Nigerian singer and rapper is arguably the number‑one artist in Africa today, and broke through in the west with his 2019 album African Giant, which was nominated for a Best World Music Album Grammy Award and won an All Africa Music Award. Last August’s follow‑up, Twice As Tall, marked Burna Boy’s first Grammy win. Ernster mixed all but three tracks of the former album, and all 15 tracks of the latter.

“There was a big difference between the two albums both in workflow and approach,” recalls Ernster. “African Giant was the first LP I had done with him, and we had not yet built up the trust. He had never even met me in person! So his deal was like: ‘Make this sound like the references. Don’t change anything!’ I tried to push him as far as I could, but he was really solid on that. I finally met him when we went to London to work on African Giant, and that is where we built some rapport. He gave me some freedom to do my thing, for example on tracks like ‘Pull Up’ and ‘Omo’.

“So with this new album he sent me unprocessed stems and raw vocals, and he gave me the freedom to treat those elements however I saw fit. This meant that I was able to dig in and build mixes that had a lot of depth, and that were really transient, really punchy, really big, really clear. It is funny, because I feel that Twice As Tall sounds 150 billion times better than African Giant, and the latter was done using a lot of analogue outboard, that people claim adds all this inherent flavour. But Twice As Tall was mixed all in the box, and I feel that the sound is so much more realised.”

Studio

Ernster conducted his mixes for Twice As Tall in ultra‑modern fashion, as he was forced to move between different places in LA, armed only with a MacBook Pro and some AirPods. He started the mixes at his home in the San Fernando Valley in LA, and quickly ran into some issues. “Because of the pandemic, travelling was not an option, unlike with African Giant. Burna was in his home in Lagos, Nigeria and not allowed to leave. We communicated via Zoom sessions, with Diddy often being there as well, as he was the executive producer. I started the mixes at my house, which was being renovated. There were jackhammers and other things going on in the background, and my wife and our daughter were staying in an AirBnB in Laurel Canyon.

With travel to Lagos off the cards, and his home undergoing a noisy renovation, Ernster had to finish his mixing work on Twice As Tall at an AirBnB in Manhattan Beach, California.

With travel to Lagos off the cards, and his home undergoing a noisy renovation, Ernster had to finish his mixing work on Twice As Tall at an AirBnB in Manhattan Beach, California.

“Because of all the noise, I joined my family, and worked on my 10‑year‑old MacBook Pro and AirPods, connecting via Remote Desktop to my Mac tower in my studio, using AudioMovers to send the session to myself. I used my phone to load the AudioMovers link to my laptop and AirPods. The audio had lengthy delay, so it took about four seconds before I heard the effects of any mix moves I made! At the same time I also often had Burna and Diddy on my screen via Zoom. It was a weird way to work. I later finished the mixes in another AirBnB on Manhattan Beach.”

Ernster’s home studio, where his work on Twice As Tall started. He has recently moved to a desk‑free setup in his home studio to eliminate deleterious reflections.Ernster would sometimes check his mixes in his studio, which had Strauss SE‑NF‑3 nearfield monitors. The reason for the past tense is that his studio is going through an almighty overhaul: “Right now my studio has become a temporary room,” explains Ernster, “because I’m converting a space in my backyard to be my new studio. It’s going to be great, with 12‑foot vaulted ceilings and awesome acoustic treatments. I can’t wait.

Ernster’s home studio, where his work on Twice As Tall started. He has recently moved to a desk‑free setup in his home studio to eliminate deleterious reflections.Ernster would sometimes check his mixes in his studio, which had Strauss SE‑NF‑3 nearfield monitors. The reason for the past tense is that his studio is going through an almighty overhaul: “Right now my studio has become a temporary room,” explains Ernster, “because I’m converting a space in my backyard to be my new studio. It’s going to be great, with 12‑foot vaulted ceilings and awesome acoustic treatments. I can’t wait.

“I’m also changing monitors. The SE‑NF‑3’s likely have the lowest distortion and are the most revealing of any speaker I know. You can reach 100 miles into that speaker and pull things out. Mixes come together far more quickly for me with those speakers. I got them after I did African Giant, and they were a game changer. I have since swapped them for Strauss SE‑MF‑4 midfields, which are even better. They’re too big for my temporary room, so for now I use tuned‑up Yamaha NS10s, which sound incredible as well.

“My other gear consists of a UREI 1178, and I also have an old blue‑stripe 1176 from 1970, the Overstayer Modular channel and a couple of modified Distressors. I have Avid HD IO and a Grace M905 DAC. I used to have a desk, but I got rid of it. My favourite piece of gear is the lack of gear in front of me now! It’s all keyboard and mouse, sitting in my lap, and I’m hearing nothing but direct, point source from the monitors without all those pesky reflections.”

New Heights

Having elaborated on his working space and gear, Ernster returned to the story of his mix of Twice As Tall, an album that saw a diverse array of producers, including Timbaland, Mike Dean, Diddy, Telz (a young Nigerian producer), and several others.

Artwork from the Twice As Tall album.“They had been working on the album for nearly a year,” recalls Ernster, “and I started receiving stems in May, and began mixing in June. We wrapped the album up in July. My process begins with loading the stems into a Pro Tools session, and then I get everything colour‑coded and arranged the way I like it. My keyboards usually are green, guitars are blue, vocal samples that are used like an instrument are pink, background vocals are purple, lead vocals are red and orange, green and dark blue are aux effect tracks, black tracks are cinematic effects, and so on.

Artwork from the Twice As Tall album.“They had been working on the album for nearly a year,” recalls Ernster, “and I started receiving stems in May, and began mixing in June. We wrapped the album up in July. My process begins with loading the stems into a Pro Tools session, and then I get everything colour‑coded and arranged the way I like it. My keyboards usually are green, guitars are blue, vocal samples that are used like an instrument are pink, background vocals are purple, lead vocals are red and orange, green and dark blue are aux effect tracks, black tracks are cinematic effects, and so on.

“My session arrangement has bass at the top, then the kick, the rest of the drums, then midrange instruments, backing vocals, lead vocals, vocal effects tracks, and finally some more aux effect tracks. I have a template of sorts, but it’s basic. It’s just my I/O and a bunch of tracks with bypassed plug‑ins, so I can check out what they do quickly. There are reverbs and delays, including Eventide MicroShift and H3000 sort of stuff, parallel distortion and parallel drum compression busses. There’s just a bunch of stuff laid out, so I can quickly get things into a space.

“Speed is very important to me when mixing. After working for more than two hours on a mix, it’s very difficult for me to get my perspective back. I can never hear it the same again, so I really rely on those first couple of hours. It’s when I’m hearing things fresh and responding emotionally. After two hours I will sleep on it, and come back to the mix the following day. Part of that is to do with the performance aspect, which I love and miss from the days of performing live. I’m not an introverted engineer. I love hanging out and creating music with people and making wild, emotional mix moves.”

Influences

Ernster says he was influenced by both his singer‑songwriter mother, and his multi‑instrumentalist/producer father, but he got most of his studio skills from the latter, who had a fully blown studio in the parental home, where his son spent many hours.

“My dad is a great guitarist and producer, and my biggest inspiration, though not my favourite mixer,” Ernster elaborates. “We disagree on many things, particularly technical. But he has my favourite musical mind! I also played drums and guitar and did the touring and sleeping‑in‑vans thing. I then got into composing, and engineering and producing, but very quickly knew that mixing is what I wanted to do.

“When producing and engineering, I realised that I was always trying to fast‑forward to get to the mixing stage. I was obsessing about guitar and snare tones. I bought amps and amp simulators, and was more into dialling in sounds than actually playing. So I decided to focus on mixing, and other than my dad, mixers who inspire me are Randy Staub, Tom and Chris Lord‑Alge, and Eric Valentine. I did a lot of reverse engineering of mixes, also using Sound On Sound’s Inside Track articles, constantly trying hard and failing!”

Ernster’s history as well as the names of his favourite mixers suggest a bias towards rock music, and he explains that he indeed likes to incorporate some rock elements in his mixes, despite the fact that most of his work today is in the hip‑hop and R&B arenas. He adds that the latter requires a slightly different mix perspective than American hip‑hop and trap.

Jesse Ray Ernster: Burna is an Afro‑fusion artist, and he’s a pioneer of the Nigerian Afrobeat sound. One thing I really like about it is that there’s a lot of percussion that occupies the upper midrange and top end with really fast transient responses. They really want that stuff upfront, sometimes way above the vocal.

“What I currently work on is actually really far from the styles of music I came up with. So there was a bit of a learning curve for me, particularly in terms of mixing bass, kick and 808s. Burna is an Afro‑fusion artist, and he’s a pioneer of the Nigerian Afrobeat sound. One thing I really like about it is that there’s a lot of percussion that occupies the upper midrange and top end with really fast transient responses. They really want that stuff upfront, sometimes way above the vocal.

“Burna, his manager, and some other people explained that to me over the last few years: ‘We know it’s loud, but trust us, that’s the sound, and it is what we want.’ So it was a learning curve to give them these bright, upfront transients, and I would also EQ and compress them a little bit, to keep them out of the way of the sibilance and consonants of the vocals. You want the vocal to be able to tell a story without being overwhelmed by the percussion.

“This relates to something I learned after coming to LA: you have to respect the reference mix. That had never occurred to me before. The mixing that I knew from Minneapolis was to evolve the song and make it sound better according to your own judgement. But it’s about realising the vision of the artist, and I had to recognise that their intent is always embedded in the reference mix. I was really freaking out artists by transforming their songs, even though I believed my mixes were technically bigger, better and wider. But it’s not what they’re used to and it’s usually not what they’re after.”

‘Time Flies’

Ernster obviously applied the mix skills and insights he gained in recent years on his mix of Twice As Tall. He illustrated his approach by elaborating on his mix of the song ‘Time Flies,’ which features Sauti Sol, a Kenyan Afro‑pop band known for its a cappella skills. The track was co‑written and co‑produced by members of the band, with American Andre Harris co‑producing. Ernster chose the track because it was the most challenging mix, and also slightly different to the other mixes.

“This song is not Afrobeat but is more in a South African style, ie. South African meets Afro‑fusion. The approach is slightly different in that it was like arranging a city of vocals. It was drums, percussion, some keyboards, and for the rest: just piles of vocals. The first challenge was to highlight the vocals. I was not hearing enough emphasis on the many gorgeous vocals in the reference mix, and so I did a lot of cutting in the low mids. The vocals were well‑recorded, but many of them were fighting to occupy the same midrange space, so I did a lot of scooping and cleaning things up and adding some silky top end.

“Another major challenge was the size of the session. Burna’s tracks typically have 30 to 100 stems, most of them drums and percussion. But in this case there were about 150 stems, with 100 of them being vocals. The session was so big, it would not even play on my computer! There were like 16 tracks with one harmony syllable. So I had to group many of the vocal stems and print them down to two‑track stems. That took 45 minutes or so. After that I was able to start the actual mix.”

Kick It

Ernster talks us through the mix, starting with the kicks: “I start my mixes with all faders up, nothing soloed. But I do like to get the low‑end foundation happening early, so after a while I will look at the kick. With this song, the kick is the first instrument that comes in, and it’s an attention grabber. I had a vision for the kick to have a powerful punch with a really fast sub low‑end, and I wanted it to be incredibly tight.

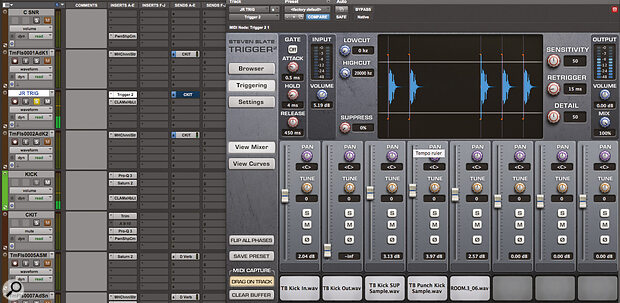

“I felt like they were going for a hard gospel kick, microphone right on the beater, with a lot of top end. Being a rock & roll guy I incorporated a little bit of that, and added a series of kick samples from a song I did with Travis Barker. It is part of what makes that kick so big. I used the Steven Slate Trigger 2 plug‑in to do this. But that plug‑in is not always phase accurate, so I’ll print the audio and then manually align the kick and the samples.

The original kick track was extensively layered with samples, using Steven Slate’s Trigger 2.

The original kick track was extensively layered with samples, using Steven Slate’s Trigger 2.

“All the kicks go to a Kick aux bus. I process that with the FabFilter Pro‑Q 3 EQ, the FabFilter Saturn 2, and the Waves CLA Mix Hub. I’m not sure how I got to that weird EQ curve on the Q 3, but I guess it sounded better like that! I like to dig in and move stuff around until I hear results. Sometimes extreme moves get you there. If you spend too much time being careful and trying to think logically about a mix, it can prevent you from making quick, instinctual moves that may push the song in the right direction. The Saturn gets more decay out of the upper mids. The kicks had extremely fast transients, and by adding length they cut better through the mix. The CLA Mix Hub is my favourite SSL E‑channel emulation right now, and it’s also making some EQ cuts.

“The Kick aux has a parallel aux track called C‑Kit. It adds more parallel saturation and distortion than compression. There’s a Pro‑Q 3 on the track notching out one click around 4kHz that bothered me, and then it goes to the Korneff Pawn Shop Comp. Its preamp is turned all the way up, adding clipping, and with the bias button you drive the tubes to distort. I really love obliterating things with distortion. That is where you get a lot of aggression. This stuff works better in parallel, whereas if you just compress it, you’d get a bit of a tired sound. Dan Korneff’s emulations of analogue gear are literally built from the schematics. To my ears they are the closest thing to real distortion from real components. It is incredible.”

Bass

“I dialled in the bass at the same time as the kick,” Ernster explains, “and from there I went straight to the vocals — I really want the song to be feeling good within the first few minutes. I had already established that the kick would be dominating the sub region, so I high‑passed the bass audio track with the Pro‑Q 3, with a slow roll‑off at 60Hz. It may sound counterintuitive, but putting a high‑pass filter on a bass guitar is a good way to get a lean and tight low‑end. After that I inserted the Kush Audio REDDI tube direct box, which beefed up the low end and gave this beautiful harmonic presence in the midrange that brought it to life.

The bass track was high‑pass filtered using FabFilter’s Pro‑Q 3, before being run through Kush Audio’s REDDI plug‑in for some saturation.

The bass track was high‑pass filtered using FabFilter’s Pro‑Q 3, before being run through Kush Audio’s REDDI plug‑in for some saturation.

“There are sends on the bass audio track to a JJ8 aux and two S Bass auxes. The JJ8 aux has the CLA Mix Hub with the microphone preamp all the way up and a high‑pass filter up to 120Hz. It sounds like an overdriven guitar. And there’s a Polyverse Wider that pushes this bass sound out left and right and adds a bit of a 3D feel. The two S Bass busses do a similar thing. They both are high‑pass‑filtered choruses, just with different flavours of chorus, one from the Avid Air and the other from the Valhalla Space Modulator. Together these two tracks add a sparkly, shiny 3D effect to the bass sound.”

Drums

Although Ernster’s next step was working on the vocals, to keep the narrative simple, he first elaborates on his drums and percussion treatments: “The main snare track has Saturn 2 to add saturation, and the other snare track has the Kush Omega Transformer, which is taming the top end. There’s also a Snaps track amongst the snares, which I treat with the Metric Halo channel strip, because the snaps were really mono and midrange‑y, with tons of 2‑3 kHz. The Metric Halo takes out the midrange and the Soundtoys MicroShift spreads them wide left and right. That was an accidental move that sounded cool.

“These three tracks all have a send to a DVerb aux, which actually has the ReVibe II, a gated non‑linear cheesy‑sounding reverb that sounds very ’80s. But I found that if it’s tucked underneath, it’s really effective at getting the snare to decay without getting in the way of the mix. By the way, towards the end of the song the snaps come in that sound twice as loud as in the rest of the song. It was a result of an accidental double stem of snaps, and I corrected that, but someone on Burna’s team had grown really fond of those snaps and said that it brings the song to a beautiful climax. So I left it in.

“Other noteworthy treatments were on the three drum fill tracks, which all have the Korneff Talkback Limiter. It’s an emulation of the early ’80s Peter Gabriel/Phil Collins technique of overloading the talkback mic, and you get this big thunderous sound. I use that a lot on Afrobeats productions, where they often program fills on separate tracks, and the Talkback adds power and excitement to those fills.

Processing on the programmed drum fills.

Processing on the programmed drum fills.

“Also, Timbaland added this incredible groove that can most clearly be heard starting at 3:28 in the song. It was very tight and very choked and sounded too much like clicking, so I added the Pro‑Q 3 to get rid of a resonance at 492Hz, and to push the high mids and high end, going into a Saturn 2 in Broken Tube mode to distort them and get more sustain and soften the top end. Finally, a Mix Hub boosts the top end to add more life and presence.

“Most of the percussion in this song was programmed, and the timing and groove worked really well. The only issue was that the drums sounded like they were in a different space. The vocals were in this mystical atmosphere, and it was the same for the synths. But the drums and percussion were right up front, and this felt very incohesive. So I added two DVerb aux tracks, which actually have the Avid ReVibe II, using a couple of presets that I like. I did not want to put reverbs straight on the drums, because that would have pushed them too far back. By adding these reverbs to the drums they lived in a similar space as the vocals and the band as a whole felt like they were performing in the same environment.”

Vocals

“The song already felt great after a few minutes of mixing,” Ernster continues. “The reference mix felt good, the beat was solid too. As I mentioned earlier, after that it was a matter of getting the vocals to shine. Dialling in the vocals took quite a bit of time on this song, because there were so many of them. This song was all about the backing vocals, getting them to sit in a place where they can shine and sparkle and just sit perfectly.

“Pretty much every background vocal on the song has the CLA Mix Hub channel strip, doing some high‑pass filtering, some EQ, and compression. I approached this mix a bit like a console mix, and dialling in every background vocal with the Mix Hub got them where I wanted them to be. I did not need 10 plug‑ins to make the background vocals sound good. This plug‑in just lit them up.

“One interesting moment with the backing vocals is in the bridge of the song. Diddy had a vision that these ‘welelel’ vocals would not only be wide but would also be wrapping around, with the panning going from left to right. So I put on the Waves S1 Shuffler, turned up the width knob and then automated the panning. It was a bold Diddy move that really paid off. It became a special moment, and is one of my favourite spots in the song.

“Underneath the ‘welelel’ track are nine backing vocal aux effect tracks, which are a ModDelay 3; 16th‑note, eighth‑note, quarter‑note and half‑note delays (all the Valhalla Delay); a ping‑pong delay (Waves H‑Delay); and all those tracks have sends to a Valhalla Vintage Verb plate and the FabFilfter Pro‑R. And all those feed the BGV FX bus. I was just moving these effects all around until they felt right.

“Burna’s main lead vocal is in red. One technique I learned from my dad is to ride the fader on vocals, so you don’t get the anomalies that you can get when compression is applied to a recorded voice. As I don’t have a fader, I chopped up the vocal and then adjusted the Clip Gain for each phrase. As for processing, I added the Gullfoss EQ, that kind of rides the frequencies, and which I love. I used it on Burna’s voice on most of the album. There’s also a Pro‑Q 3 to notch out some frequencies, and the Acustica Amber 3 EQ, which adds the most gorgeous top end.

“There’s a send on the main lead vocal to an aux with the Soundtoys Devil‑Loc, adding parallel distortion. It’s a bus I try once in a while. If the vocal is sitting where I want it to sit in the mix volume‑wise, but it needs a little bit more glue, body and warmth, I’ll go for the Devil‑Loc. It brings the vocal straight up into your face. If you want a pop vocal that is right on top of everything, this is it.

“I also have other vocal aux effect tracks, ie. different delays, reverbs, pitch‑shifts. I generally do not use reverbs on the lead vocal, but only delays, because they take up less space. Then I’ll have a delay to feed a reverb that can sit in the background. The pre‑delay creates this ocean of ambience that does not take away from the intimacy and upfront nature of the lead vocal.

“There are a couple of tracks called ‘Throw’, and I create those by dragging duplicate audio to a separate track, and then putting an effect on with the mix at 100 percent, in this case Valhalla Delays. I don’t really like using automation on sends and muting and so on, as it’s a really slow workflow. It takes one second to drag down some audio, add a delay and done.

Ernster’s method for widening the lead vocal involves using Pro Tools’ Time Adjuster plug‑in with Valhalla Space Modulator, to emulate the Eventide H3000’s doubling effect.

Ernster’s method for widening the lead vocal involves using Pro Tools’ Time Adjuster plug‑in with Valhalla Space Modulator, to emulate the Eventide H3000’s doubling effect.

“Below the ‘Throw’ tracks are two Time Adjuster aux tracks and a Valhalla Space Modulator aux track. Together they recreate the Eventide H3000 wide vocal effect. The Time Adjuster plug‑in delays the left and right channels a bit, and one channel has the CLA MixHub to add some distortion and the other channel has the lo‑fi. The Valhalla Space Modulator is followed by a Cranesong Phoenix II, driving really hard in Dark Essence mode. These three go to an aux called ‘SHIFT M’, and it turns a mono vocal into a wide, enveloping, beautiful vocal. Also, there’s a ‘Lead Vocal All FX’ aux with the Pro‑Q 3 EQ that takes out all top and bottom, which you don’t need on vocal effects.”

Jesse Ray Ernster: My master bus chain starts with the Acustica Sand 3 compressor, followed by the Korneff Pawn Shop compressor. Neither of them do any compressing, but the Sand adds a very subtle VCA colour that you get from an SSL bus compressor, and the Pawn Shop adds a little bit of tube saturation.

Master Bus

“My master bus chain starts with the Acustica Sand 3 compressor, followed by the Korneff Pawn Shop compressor. Neither of them do any compressing, but the Sand adds a very subtle VCA colour that you get from an SSL bus compressor, and the Pawn Shop adds a little bit of tube saturation. Next is the Waves Abbey Road TG Mastering Chain, which has a really accurate and phase‑coherent Spreader knob. It’s set to +2, and I also do some minor EQ adjustments with it.

“Next up is the FabFilter Pro‑MB multiband compressor. The low end, around 60Hz, in this song was a bit floppy, and I wanted to tighten it. I used a slow attack and slow release and was able to get the subs to breathe with the song’s tempo. The Acustica Purple 2 Pultec clone boosts 16kHz and attenuates at 10kHz. This is a big part of the top end of the record.

“Following it is the Phoenix II, which I drive just enough so the kick starts to clip, almost like breakbeat or even like what Dr Dre did in the ’90s, and then I back it off slightly. This adds some life to the midrange by using harmonic distortion. Finally, the FabFilter Pro‑L adds 2‑3 dB of loudness, and the SIR Audio Tools StandardCLIP another 1.6dB of gain. Both are there so I can compete with the reference mix, and I took them off when I sent the song to mastering. There’s also an Audio Systems Metric AB, which allows me to A/B my mix against the ref. I spend a lot of time with that plug‑in!”