Screen 1: Groove Delay can be made to work for widening a guitar into stereo by setting two taps to their shortest range and then sliding one a little ahead or behind the other, but delay times are tempo-dependent. Tap 2 settings are shown here: note how the Groove control is set to Dotted.

Screen 1: Groove Delay can be made to work for widening a guitar into stereo by setting two taps to their shortest range and then sliding one a little ahead or behind the other, but delay times are tempo-dependent. Tap 2 settings are shown here: note how the Groove control is set to Dotted.

Add artificial stereo width to guitars in your Studio One mixes.

Most people have tried making a guitar track sound bigger by throwing a long echo or lush reverb tail onto it. Sometimes, though, a different kind of size is needed. Acousticians speak of “apparent source width”, and a wider image can be just the thing to make a guitar feel larger when the music is too fast and loud for a lot of delay, or the mix needs to remain uncluttered.

This month I look at one of my favourite methods of accomplishing this. I usually try in this column to stick to Studio One’s bundled plug-ins as much as possible, but in this case there are third-party plug-ins better suited to achieving these effects. These techniques work with vocals and many other sources, but I just finished mixing Cosmic Mercy’s Enjoy The Ride, a guitar-heavy album on which I heavily applied widening techniques, so that is how I will present them. My starting assumption is that the guitar track is mono, which means much of the goal lies simply in making it stereo. Mono-to-stereo techniques can be effective, but are not all there is to making the guitar feel wider.

Wait Up

Short delays are the foundation of many widening techniques, both in acoustics and in mixing, but the range of delays involved in natural acoustics and multitrack mixing differ by orders of magnitude. In acoustics, interaural time delay (the difference in arrival time at the two ears) is often on the order of microseconds. Creating such delays artificially at the mix can be difficult, while the results can be disappointing, and tend to work better over earbuds or headphones than on speakers.

Delays of a few milliseconds are more effective for widening in mixing. The upper limit is when the delay is long enough that it becomes perceived separately from the signal rather than fused with it, which I find happens when the delay reaches around 20ms. Longer delays are definitely useful in widening an image, but the effect is different, and mixing has to be handled somewhat differently as a result.

The basic technique I use most is to put the original signal in or near the centre and use short delays of slightly different lengths on each side — so I might have a delay of 6 or 8ms on one side and one of 10ms or so on the other. (Exact values vary with the circumstances, of course.) Unfortunately, this is not easy to achieve with Studio One’s bundled Analog Delay, Beat Delay or Groove Delay, partly because the popularity of tempo-sync’ed delays has resulted in more emphasis on plug-ins capable of locking to the song’s tempo. All three of Studio One’s bundled delays can be tempo-sync’ed, but only the Analog Delay plug-in allows times to be set in milliseconds instead, by deselecting the Sync button below the Beats control in the Time section.

Even then, obtaining delays in the order of just a few milliseconds with Analog Delay’s Beats knob is difficult: the delay value doesn’t even go below 100ms until you are nearly at the start of the knob’s travel. To get a delay of 8 or 10 ms, you must manually enter the desired value. Once you do that, you still face the problem that the Analog Delay is only a single-tap delay, making it impossible to set different delay times for each channel. The closest you can come is by adding some feedback (which I generally avoid in this application) and setting the Width control to wide Stereo or Ping Pong. Workarounds include using two Analog Delays set to different times and hard-panning them, or duplicating the guitar track and using track delay, but it seems like a lot of work to me just to get two simple, short delays.

Despite the fact that it doesn’t allow delay times to be set in milliseconds, it’s easier to achieve this using Groove Delay. This is a versatile plug-in offering four taps, each of which can have different levels, panning and even filtering. For now, we’ll just use two taps. To get close to the delay times I’m talking about you’ll have to set the basic delay time as low as possibly by dialling the Beats control down to 1 and setting the Beatlength control in the Grid section to 1/64.

Assuming delays are hard-panned to opposite sides, the width of the image is generally greater with longer delay times between the dry and delayed signals, and between the left and right delay times. However, both of these can be temperamental, especially the latter, and I frequently use delays that are not too different from each other. To get two delays that are close in time, set two taps the same and then use the Groove control on one of them to slide it a little ahead or behind the other. Changing Beatlength to 1/32 on one of the taps gives you a much greater difference between the taps.

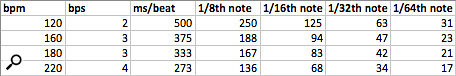

Screen 2: With tempo-sync’ed delays, actual delay times vary with the tempo. Beats per second is ‘bps’ in this chart. The audio examples are at a tempo of 120bpm, making the shortest available delay time 31ms, or a bit less using the Groove control.

Screen 2: With tempo-sync’ed delays, actual delay times vary with the tempo. Beats per second is ‘bps’ in this chart. The audio examples are at a tempo of 120bpm, making the shortest available delay time 31ms, or a bit less using the Groove control.

Now we come to another limitation, which is that since the delay times are tempo-sync’ed, the shortest delay time is determined by the tempo. As shown in Screen 2, to even get under 20ms requires setting the tempo about 180bpm. The only way this works conveniently is if the song is very fast or if you are not working to the bar/beat grid — that is, all the tracks are audio, not recorded to Studio One’s click, and not sequenced. Once again, there are a few workarounds that seem to me more hassle than they are worth.

As an alternative, I often end up simply reaching for Waves’ SuperTap plug-in, which lets me set two taps to separate, short, delay times; and just as often, I turn to my trusty Lexicon PCM70 for delay effects. In the plug-in world, even the delay plug-ins capable of sufficiently short times and having two taps tend to be far more complex than is needed, in fact, the ones that seem best suited to this technique are both Lexicon delay emulations: SoundToys’ Primal Tap and PSP Audioware’s PSP 85.

In The Mix

Screen 3: Setting up widening delays as send effects and then submixing them with the dry signal offers the flexibility to treat the delays differently from the dry sound, then treat them together. In this example, the submix is compressed with a UAD Fairchild 670. Note that the dry guitar is panned to the right to keep the image balanced around the centre, since the longer delay is panned left.With your twin taps in place, the question is how pronounced you want the effect to be. To get a full and wide sound, mix the hard-panned delays higher than the dry signal; for some situations you may leave out the dry signal altogether. You might find that the image sometimes seems to pull towards the side of the shorter delay. If so, panning the dry signal a bit to the opposite side can restore an even balance. For a less pronounced effect, try panning the delays in a bit from the sides, and/or rolling off the high frequencies on the delay channels. This is one thing that Groove Delay makes easy: just set each delay to have a low-pass filter with a cutoff down around 3kHz or even less. Low-pass filtering also often enables the use of longer delay times. However, remember that panning the dry signal and delays closer together will produce comb-filtering.

Screen 3: Setting up widening delays as send effects and then submixing them with the dry signal offers the flexibility to treat the delays differently from the dry sound, then treat them together. In this example, the submix is compressed with a UAD Fairchild 670. Note that the dry guitar is panned to the right to keep the image balanced around the centre, since the longer delay is panned left.With your twin taps in place, the question is how pronounced you want the effect to be. To get a full and wide sound, mix the hard-panned delays higher than the dry signal; for some situations you may leave out the dry signal altogether. You might find that the image sometimes seems to pull towards the side of the shorter delay. If so, panning the dry signal a bit to the opposite side can restore an even balance. For a less pronounced effect, try panning the delays in a bit from the sides, and/or rolling off the high frequencies on the delay channels. This is one thing that Groove Delay makes easy: just set each delay to have a low-pass filter with a cutoff down around 3kHz or even less. Low-pass filtering also often enables the use of longer delay times. However, remember that panning the dry signal and delays closer together will produce comb-filtering.

Most often I set the delays up as send effects rather than insert effects, then submix the dry and delay channels to a bus channel. This lets you apply further treatment, such as compression, to the composite mix. Mid-sides processing can also be used to exaggerate the widening effect: try emphasising the Sides signal a little by lowering the Mid signal or adding compression or EQ to the Sides signal. Mid-sides processing can also work nicely when applied to another mono-to-stereo technique: band-splitting.

Early reflections and small-room reverbs can also be used to create a wider image, but if widening is the primary concern, it is important to minimise the amount of late reverb relative to early reflections and to be sure the decay time of the late reverb is no more than 1 second, and preferably less. I find Studio One’s Open Air reverb better for this application than Room Reverb, but Room Reverb can be made to work. If widening using the delay technique produces an effect that sounds too discrete, mixing in a very small amount of early reflection ambience can smooth it.

With a wider image, other processing, such as chorusing and/or longer reverbs, can be added for fatness and depth, but those are a whole different story. Remember that the purpose of chorusing and reverb is to smear, and applying them too heavily can lessen the intensity of the widening effect. Finally, whatever widening effect you choose, it’s important to make sure that you audition the mix in mono to check that it’s not completely mucking up your mix balance or your guitar sound.

Six Strings Good, 12 Strings Better?

Guitars don’t always need a wide image. Rhythm guitars are often better when they can be tucked into one spot in the stereo panorama, for example. But when a guitar is prominent in the mix, a widened image can make it feel more upfront without it having to dominate level-wise.

Audio Examples

You can download the zip file from the sidebar to hear audio files illustrating the following:

- The dry guitar in the context of a simple mix.

- The guitar widened with the Groove Delay setup shown in Screen 1.

- The guitar widened with the SuperTap setup shown in Screen 2, then further enhanced with some echo.

Download | 29 MB