The main screen of Cinematic Lights hosts a number of macro controls and a three‑way vector pad for blending between the layers.

The main screen of Cinematic Lights hosts a number of macro controls and a three‑way vector pad for blending between the layers.

We explore the new Cinematic Lights virtual instrument.

In January's v7.1 Studio One update, PreSonus gifted us a new virtual instrument called Cinematic Lights. It’s designed to blend heavily processed strings and brass with synth, modular and environmental elements to offer complex textures, smooth transformations and multiple layers of movie magic.

Cinematic Lights is based on the core Presence XT engine and so is essentially a multisampled instrument library. It uses an overhauled front end to give you more intuitive and creative control over how the sounds are layered and modulated. We find similar ideas in Deep Flight One and Lead Architect, which came with the initial release of version 7.0. This new hybrid instrument comes with 120 sampled sounds, 120 layer presets, 96 instruments and 50 Musicloops. So let’s dig in.

Layer Cake

The front end of Cinematic Lights mirrors the instrument’s intention: it’s moody, interestingly lit and asking for interaction. When you lay your hands on the keys, the default preset is exactly what you’d think; I half expected the background to spring into life with illuminated flying objects, moodily moving figures and the stings of a few drops of rain. Instead, we have some controls to play with.

The detailed layer editor gives you direct access to each layer’s amp, filter and modulation options.

The detailed layer editor gives you direct access to each layer’s amp, filter and modulation options.

A preset is made up of three layers represented in yellow, green and red. The layers can be seen at the bottom of the GUI and have their own controls for panning, reverb and delay. Clicking the little down arrow opens the instrument browser, where you can select your sound from seven categories. However, it’s the strange arrangement of triangles in the middle of the panel that really catches your eye. The Triangle Vector Pad is like a three‑axis X/Y pad, or a three‑edged vector synthesis system. As you drag the little white triangle in the space, the three coloured lines on each side expand and contract to reflect the position. The lines correspond to the volume of the associated layer and so as you move you get a different blend of sound. If you click on the even smaller triangles at the points of the middle triangle, the mix goes 100 percent to that layer, essentially acting as a layer solo. It’s much less complicated than it sounds. All you have to do is hold a chord and move the white triangle and it becomes obvious very quickly.

To the right is an Attack and Release envelope for each of the layers, split into their colours. There’s a full ADSR envelope behind the scenes that we’ll come to in a minute, but for now, PreSonus feel that the journey into the sound and back out again are the most important aspects of the multi‑layered sound.

Over on the left is a master filter cutoff. It’s tied to the filter cutoff in each of the layers and gives you an easy way to control the timbre of the whole instrument.

Next to that is the slightly mysterious Sample Shift. The idea behind Sample Shift is that it changes the speed of the underlying sample without altering the pitch. This results in some quite interesting tonal shifts. According to the Presence manual, Sample Shift should be able to go from ‑36 to +36 semitones, and in the Presence XT instrument, it certainly does. In Cinematic Lights, however, the up/down buttons shift it ±1 octave, with no other values on offer. The only way to access the full range appears to be to map a MIDI control to it. It seems an odd oversight for a control that’s given prominence on the front panel.

Macro Polo

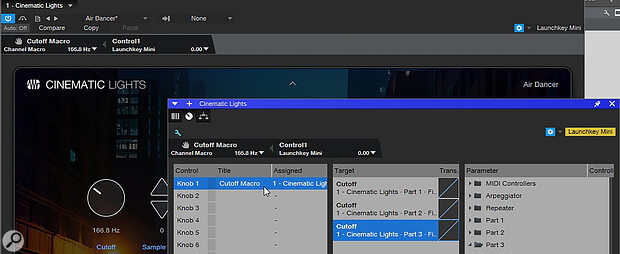

Before we move onto the effects and deeper layer editing, it would be a good idea to talk about how best to interact with the front panel. Essentially, it’s a macro interface that works well with your mouse to give you overall control of some choice aspects, but it’s less adept at MIDI control. Whenever you attempt to map a MIDI control to anything on the front end, it only gets attached to the first layer.

If you map a MIDI CC to a front‑panel control, it will only adjust the first layer. To map a controller to another layer’s parameter, you need to create a macro in the Channel Editor.

If you map a MIDI CC to a front‑panel control, it will only adjust the first layer. To map a controller to another layer’s parameter, you need to create a macro in the Channel Editor.

We can get around this by generating our own macro controls in the Channel Editor. You can bring up the Channel Editor window by clicking on the track number or the little hand of cards icon on the console channel strip. Then click on the little knob icon to bring up the macro window. It should have nothing assigned to it, so click on the little spanner icon to get us into the editor. On the right, you’ll find all the available parameters in Cinematic Lights listed. You’ll find the filter cutoff controls under each Part. Simply drag each entry into the middle section and your macro knob will control all three. Now, if you click the ‘Edit mapping’ over on the top right you’ll be able to assign a MIDI knob to control the macro and so control all three layers’ filters at once. You could do the same for the envelope attack and release.

The Triangle Vector Pad can be automated, in which case each axis gets its own automation lane.

The Triangle Vector Pad can be automated, in which case each axis gets its own automation lane.

The Triangle Vector Pad is another matter. You’d need some kind of three‑dimensional controller to let you blend and mix three sources with one control. You can use a knob for each layer level or even a single knob that crossfades between two, but that’s as far as we can go. The one route open to you is through automation. If you enable Write automation and set Studio One in motion, the level movements of all three layers will be recorded on to separate lanes as you manipulate the triangles. Alternatively, you can add waveshapes and write in modulation to the track for the individual parts to mess about with the blend.

Global FX

Squeezed between the part selection section and the keyboard is the Global FX section. It offers an overall volume control and a mix knob for the reverb and delay. This is also where we encounter the Arpeggiator and Repeater, which are MIDI note effects rather than audio processors.

Each part layer has a send control for the reverb and delay, where you set the level of signal from that part being routed to them, but it’s here in the Global FX that you set the overall return level of those effects. If you click on the effect label a new panel slides out, giving you a handful of controls over the size of the reverb, and the timing and feedback on the delay.

The Arpeggiator allows you to program your own rhythms, with up to 32 steps and adjustable gate length and velocity.

The Arpeggiator allows you to program your own rhythms, with up to 32 steps and adjustable gate length and velocity.

The Arpeggiator has aspects of a conventional arp, in that it will play whatever notes you hold down in a number of different directions. However, you can also create rhythmic patterns to run the arpeggiator groove, giving it a bit more spice. The editor is on the small side, but you can program up to 32 steps with gate length and note velocity. Simply click on the steps to drag out the gate and velocity values, and enjoy how it complements the regular play directions. There’s a bunch of presets to enjoy from a drop‑down menu on the left. Sadly, you can’t save your own.

Like the Arpeggiator, the Repeater is a MIDI effect, and can go beyond simple note retriggering thanks to its built‑in basic sequencer.

Like the Arpeggiator, the Repeater is a MIDI effect, and can go beyond simple note retriggering thanks to its built‑in basic sequencer.

Alternatively, you can run the Repeater, which retriggers the note you’ve just played up to 32 times. You can set velocity and timing, including whether it’s sync’ed to the tempo or free‑flowing. But perhaps more interestingly, you can scale the velocity so that it gets louder or softer with every repeat, or scale the pitch so it rises or falls from the original note. But wait, there’s more. You can also decouple the scaling and set the pitch and velocity individually for each step, effectively turning it into a cool little sequencer. One thing you can’t do is loop the sequence, so if you wanted it to play continuously, you’d have to drop a note into the main Studio One sequencer at the start of each bar.

Interestingly, you can enable the Arpeggiator or Repeater for each layer individually, giving a really nice depth of movement and variation to a preset.

Digging Deep

Each layer has a more detailed view, which you can access by clicking on the loaded part. The details will be familiar to anyone who’s used Presence XT. You get two LFOs with multiple waveshapes, rate control, and a useful delay function to hold back the modulation so that it doesn’t kick in until sometime after you’ve played the note. The rate can also be scaled by the notes being played so the LFO will be faster with higher notes and slower with lower.

The filter is nicely comprehensive, with multiple modes and characterful controls. You can select some of the modes on the row of buttons, but you’ll find more hidden away under the drop‑down menu. Essentially, you get every sort of ladder filter and every state‑variable filter plus a simple Eco filter that is easier on the CPU. For character variation we have a Soft button for a more mellow tone, Drive for saturation and Punch adds a bit of percussive attack. The filter can be pushed into self‑oscillation if you select the Eco variant and wind up the resonance. The Key control will alter the cutoff frequency as you play up and down the keyboard, and if you set it to maximum you can play an oscillating filter like another oscillator. You still have to have a sound loaded, but it can be quite an effective additional tone.

One tip while you’re trying to find sounds that combine well with a self‑oscillating filter is that there’s a little padlock next to where you load each layer sound. If you enable the lock, all the editor settings, including the filter, will remain unchanged, and only the samples will be loaded. It’s a great way of auditioning new sounds in a patch without losing all the editing and modulation settings you’ve been working on.

The amp and filter both get an ADSR envelope, although funnily enough, the filter envelope isn’t hardwired to the cutoff. You have to make that connection in the modulation matrix, which I’ll come to shortly, where it’s called Env2. This envelope also has a delay parameter so you can control when it starts to have an effect.

In the FX A and FX B sections, we get a bunch of layer‑specific audio effects. These include chorus, flanger, phaser, bit‑crusher, distortion (with multiple types), a gater (which acts on the audio, not the MIDI notes like the Repeater does), an EQ and a panning effect.

Lastly, we have the huge 16‑slot modulation matrix, which you may struggle to fully populate with parameters. There are actually 18 destinations, so you could certainly fill it, but you might have to double up on some of the 14 modulation sources. You put your main choice of modulator at the top, and then you can add a second modulator that the first one can be modulated by. So you could, for example, shape an LFO with an envelope. In the bottom slot, you put the parameter you are trying to control and then the line in the middle sets how deep the modulation goes and whether it’s positive or negative. It’s a potent modulation system capable of swirling these samples inside out.

Musicloops are a Studio One file format that can contain audio and MIDI information, including the virtual instrument used and the routing.

Be Inspired

If you’re not really sure where to go with Cinematic Lights then I’d recommend making use of the included Musicloops to stir up some ideas. Musicloops are a Studio One file format that can contain audio and MIDI information, including the virtual instrument used and the routing. You can use them for audio clips or MIDI phrases, but they are best when dragged into space where they can create a track and load up their intended virtual instrument.

You’ll find the Cinematic Lights Musicloops in the Browser under Files / Sound Sets / Cinematic Lights / Musicloops. They are listed with key and tempo information and should shove you down the right road.