Our countdown of the most influential music tech breakthroughs reaches the Top 20.

To mark the 40th anniversary of your favourite music recording magazine, we’ve put together our own league table of the 40 most important technical achievements in the history of recorded music. We begin the third instalment in the dark days of World War II...

20: AC bias

Early in the history of magnetic recording, it was discovered that impressing a strong, fixed bias signal onto the medium ensured that it operated within its linear zone, reducing noise and distortion. In early wire recorders and tape machines, a simple DC signal was used, but in the late ’30s and early ’40s, various researchers more or less independently discovered that employing an AC signal instead resulted in dramatic performance improvements. The effect was first exploited commercially by AEG during WWII, reducing noise to the point where it was no longer possible for the Allies to discern whether a radio broadcast was live or pre‑recorded. After the war, two of these AC‑biased Magnetophon machines were taken back to the USA, where they inspired the creation of the first Ampex tape recorders.

As well as inspiring the tape recording revolution in the USA, AEG Magnetophon recorders also ended up behind the Iron Curtain, like this one from a Russian military museum.Photo: George Shuklin

As well as inspiring the tape recording revolution in the USA, AEG Magnetophon recorders also ended up behind the Iron Curtain, like this one from a Russian military museum.Photo: George Shuklin

19: Parametric equalisation

In telephony and other early audio technologies, the frequency content of a signal could become skewed in unwanted ways, for example by high‑frequency loss in long cable runs. The earliest equalisers were simple filters that could correct this loss to restore an ‘equal’ balance of frequencies. Studio engineers were quick to realise that these filters could be used to ‘improve’ signals as well as to restore them, but they remained relatively inflexible until the invention of the parametric equaliser. The term seems to have been coined by George Massenburg, working with Burgess Macneal and Bob Meushaw, but Daniel Flickinger patented the first practical implementation in 1971. Suddenly, it was possible not only to sweep an equaliser through the frequency range to locate the region of interest, but to determine how focused the cut or boost needed to be. Parametric EQ quickly became a standard tool in the audio engineer’s armoury.

18: Lossy data compression

In the ’80s, file sizes and bandwidth limits presented serious obstacles to the distribution of digital audio. Yet it was widely understood that many of the ones and zeroes in a digital bitstream represented content that was imperceptible. Could the size of the bitstream be reduced by, in effect, including only the information that was audible? Indeed it could, and numerous different technical solutions had been developed by the end of the decade. The direct effect on music recording and production was minimal, but the indirect effect was devastating. When the MPEG Audio Layer 3 standard was adopted in the early ’90s, it was envisaged that end users would only ever access MP3 decoders; encoding would remain a tightly controlled, proprietary process. Instead, both encoders and decoders became ubiquitous and free, and file‑sharing services such as Napster wiped out music industry revenues almost overnight.

17: The Portastudio

In 1979, Tascam kicked off a revolution in recording when they released the first Portastudio, a compact (for then!) four‑track cassette recorder with a simple built‑in mixer that made low‑cost multitrack recording accessible to the bedroom musician, and let professionals make demos pretty much anywhere — and, as in the famous case of Bruce Springsteen’s Nebraska, even more than just demos! As well as the machines themselves being more affordable than the open‑reel tape recorders that had previously been a necessity, so too was the medium, and cassettes were readily available on every high street. Various models followed from Tascam and others before, in 1995, Fostex kicked things up a notch with the DMT8, the first digital eight‑track hard‑disk recorder/mixer, which brought us innovations like basic cut and paste editing and instant locate functionality.

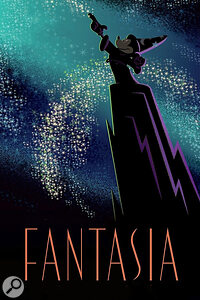

16: The click track

The single project responsible for the greatest number of innovations in the history of recorded music is surely Disney’s Fantasia. Released in 1940, this animated masterpiece is credited with the first use of surround sound, the first simultaneous multitrack recording, the invention of the pan pot, and possibly the first use of overdubbing. It also pioneered an all‑analogue form of mix automation. Leopold Stokowski’s orchestra was tracked using more than 30 mics at once, with eight optical recorders capturing the audio and a ninth yet another first: a track containing regular pulses that could later be used to time overdubs and synchronise the animators’ work. Needless to say, it would be many years before the click track began to shape the sound of rock and pop music.

The single project responsible for the greatest number of innovations in the history of recorded music is surely Disney’s Fantasia. Released in 1940, this animated masterpiece is credited with the first use of surround sound, the first simultaneous multitrack recording, the invention of the pan pot, and possibly the first use of overdubbing. It also pioneered an all‑analogue form of mix automation. Leopold Stokowski’s orchestra was tracked using more than 30 mics at once, with eight optical recorders capturing the audio and a ninth yet another first: a track containing regular pulses that could later be used to time overdubs and synchronise the animators’ work. Needless to say, it would be many years before the click track began to shape the sound of rock and pop music.

15: The MIDI+Audio DAW

Whilst Digidesign’s 1989 Pro Tools software is often credited as the ‘first computer DAW’ in that it offered four‑track digital audio recording/editing running on a Mac, it was Studio Vision from Opcode Systems, launched in the following year, that was the first program to offer integrated audio and MIDI recording to a common timeline, pioneering the model for all today’s software DAWs. Being first doesn’t always get you the win, however, and the limited power of the computers of the day, as well as limited hard‑drive capacity and expensive RAM, meant that Studio Vision failed to expand its user base beyond the professional arena. A subsequent, ill‑fated acquisition by the Gibson guitar company led to Opcode’s rapid demise, and they never capitalised on their pioneering work. A number of the key developers at Opcode went on to work with Digidesign/Avid (Pro Tools), Apple (Logic, and Core Audio), MOTU (Digital Performer) and other prominent DAW companies.

14: Artificial reverb

As Jason O’Bryan explained in September 2025’s SOS, the use of reverberation as an effect has its origins outside the music industry. Large radio broadcasters had their own echo chambers as far back as the early ’20s, at a time when records were made entirely acoustically. Music studios followed suit in the 1940s, and the Harmonicats’ ‘Peg O’ My Heart’, recorded by Bill Putnam Sr and released in 1947, was hailed for its innovative sound. As is so often the case, however, Hollywood was years ahead. The first commercially released movie soundtrack album, Songs From Disney’s Snow White And The Seven Dwarfs, was released in January 1938, and makes clever use of artificial reverb on ‘I’m Wishing’.

13: Remixing

The dancehalls of Jamaica and the nightclubs of New York provided record producers with very direct feedback. A three‑minute single might be over too soon, or might contain one short section that drove the crowd wild. Producers like King Tubby and Lee Scratch Perry began creating alternative interpretations of the reggae records they were making, de‑emphasising the vocals and incorporating varied effects. Soon, dub mixing became an artform in its own right. Then, in ’70s New York, DJs began to work with tape, chopping up and looping segments of disco records. Artists and producers started to be involved in remixing their own work, with the 12‑inch single becoming the format of choice. By the time house music took off, remixing was a specialist career for some, and in the hands of producers like Aphex Twin, would eventually reach the point where a ‘remix’ might be a completely different track in all but name.

Musicians have been plotting to get rid of drummers for a surprisingly long time.

12: The drum machine

Musicians have been plotting to get rid of drummers for a surprisingly long time. Léon Theremin, inventor of the instrument that bears his name, produced a device called the Rhythmicon way back in 1932. From the ’50s onwards, drum machines that could play back a selection of preset rhythms became common add‑ons to home organs, and by the late ’60s some pop artists were experimenting with them on record. However, it was the advent of the microprocessor‑controlled, programmable drum machine towards the end of the ’70s that moved synthesized rhythms out of the realms of novelty. The Roland CR‑78 and TR‑808, which generated their drum sounds using analogue circuitry, vied with sample‑based units like the Linn LM‑1 and Oberheim DMX; and music was the winner.

The Roland CR‑78 was the first programmable drum machine that could store and replay user‑created rhythms — as long as you also had the super‑rare WS‑1 ‘write switch’.

The Roland CR‑78 was the first programmable drum machine that could store and replay user‑created rhythms — as long as you also had the super‑rare WS‑1 ‘write switch’.

11: Stage monitoring

One of the reasons why the Beatles retired from live performance in 1966 was that sound reinforcement technology couldn’t keep up with their popularity. The PA systems of the time were no match for stadiums full of screaming teenagers. Over the next 10 years, live sound would undergo a complete revolution, from simple column speakers designed only to amplify the vocal microphone to complex arrays through which the entire band would be presented, sometimes in stereo or even quadraphonic sound. Perhaps the most revolutionary step in this process was the introduction of additional speakers on stage to direct these amplified signals back at the artists. Stage monitors first appeared around 1969 and were likely developed independently by several different FOH engineers, among them Bob Pridden with the Who.