Our 4-part series concludes with the 10 most significant technological developments that have shaped — and continue to shape — everything we hear.

October 2025 marked 40 years since the first issue of this magazine hit the newsagents’ shelves. Sound On Sound has stayed at the cutting edge through non‑stop technological change and disruption. We finish our look back at the milestones of music tech with the 10 that, in our view, have proved most important of all.

10: Compression

In radio, it was desirable for the programme level to be close to the maximum permitted, as this would create the strongest signal. But going past this maximum could have serious consequences and even damage the transmission equipment. Hence radio stations began to invest in limiters: devices that could prevent the signal level exceeding a desired ‘threshold’. The first commercially available units appeared as early as 1931, and by the early ’50s, broadcast compressor‑limiters had become quite sophisticated. Their initial use in music recording was in disc cutting, where they served a similar protective purpose, but it was not long before imaginative engineers such as Joe Meek began to find creative applications for them. Soon it became common practice to use compressors on individual instruments during tracking, as heard for example on Ringo Starr’s drumming or Roger McGuinn’s guitar. The sound of pop music would be very different without it!

9: The unidirectional microphone capsule

The Shure Model 55 was the first mass‑produced unidirectional moving‑coil microphone.The vast majority of microphones sold these days have a cardioid polar pattern. They pick up sound from the front and reject sound from the rear, and we can point them at sound sources in the same way we might illuminate a picture with a spotlight. But it wasn’t always thus. Basic microphone design allows the construction either of a pure pressure mic, which has an omni pattern, or a pressure gradient mic, which has a native figure‑8 pattern. Early attempts to create a unidirectional mic involved combining an omnidirectional moving‑coil capsule with a figure‑8 ribbon motor, with less than perfect results. The problem of creating a single capsule with a cardioid polar pattern was solved independently by Ben Bauer at Shure, who created the single‑diaphragm Unidyne capsule, and by Dr Hans Joachim von Braunmühl and Walter Weber, who invented the dual‑diaphragm capacitor capsule.

The Shure Model 55 was the first mass‑produced unidirectional moving‑coil microphone.The vast majority of microphones sold these days have a cardioid polar pattern. They pick up sound from the front and reject sound from the rear, and we can point them at sound sources in the same way we might illuminate a picture with a spotlight. But it wasn’t always thus. Basic microphone design allows the construction either of a pure pressure mic, which has an omni pattern, or a pressure gradient mic, which has a native figure‑8 pattern. Early attempts to create a unidirectional mic involved combining an omnidirectional moving‑coil capsule with a figure‑8 ribbon motor, with less than perfect results. The problem of creating a single capsule with a cardioid polar pattern was solved independently by Ben Bauer at Shure, who created the single‑diaphragm Unidyne capsule, and by Dr Hans Joachim von Braunmühl and Walter Weber, who invented the dual‑diaphragm capacitor capsule.

8: Sampling

In a general sense, ‘sampling’ is the process by which an analogue‑to‑digital converter translates a fluctuating voltage into a stream of numbers. In early digital recorders, this stream of numbers was then simply written to a medium such as magnetic tape. The great innovation of Australian designers Kim Ryrie and Peter Vogel was to retain these sequences of numbers within random access memory (RAM), allowing them to be manipulated in real time. Together, they created the immortal Fairlight Computer Musical Instrument.

The Fairlight Computer Musical Instrument introduced sampling to the world.

The Fairlight Computer Musical Instrument introduced sampling to the world.

7: Overdubbing

The AC‑biased tape recorder proved a revolutionary device in more ways than one. As well as offering unprecedented sound quality, it allowed recordings to be altered after the fact. Composite performances could be edited together from multiple takes, and by temporarily disabling the machine’s erase head, it was possible to layer a second performance on top of a first. This technique, which gives Sound On Sound its name, was pioneered by Les Paul using a disc cutting machine, and perfected when Bing Crosby gave him an early Ampex recorder in 1949. ‘How High The Moon’, recorded thus with his wife Mary Ford, was a big hit in 1951.

The idea of having sound generation triggered by the playback of stored data long pre‑dates electronic music.

6: Sequencing

The idea of having sound generation triggered by the playback of stored data long pre‑dates electronic music. In the early part of the 20th Century, the player piano or pianola became hugely popular, and there were even standard formats for piano rolls so that the same music could be played on most manufacturers’ instruments. Later, more sophisticated systems incorporated an ever‑increasing degree of musical expression. The key difference compared with sequencing as we know it today is that the player piano was really a playback‑only device. It was not until analogue sequencers and early experiments in computer‑based music that the sequencer became a compositional tool. Then, 75 years after player‑piano manufacturers had met in Buffalo to agree on a universal format for paper‑based sequencing, MIDI happened... and the rest is history.

5: Stereo

Literally, the coinage ‘stereophonic’ translates as ‘solid‑sounding’, and it was EMI engineer Alan Blumlein who established that such a phenomenon could be created using two spaced loudspeakers, playing back different but related signals. Blumlein also invented the coincident miking array that bears his name, and was the first to show that a two‑channel stereo signal could be represented as ‘sum and difference’ or Mid and Sides. Crucially, he also developed practical tools that could make stereo recording and reproduction a reality, demonstrating that a single groove on a record could contain two signals simultaneously. Blumlein applied to patent his inventions late in 1931, and he was not far ahead of Bell Laboratories, Disney and other American pioneers.

4: Editing

Today, recorded sound is infinitely malleable. It didn’t get that way overnight. Early media such as wax cylinders and disc recorders simply documented what was put in front of them, imperfectly and finally. Probably the biggest single step along the path to today’s state of affairs was the popularisation of tape as a recording medium after the Second World War. Tape could be recorded on more than once, a property which enabled the invention of the 'drop‑in'. Its comparatively flawless sound quality made it feasible not only to record direct from life, but to re‑record from another tape machine. It could be played backwards, for otherworldly effects. And tape could be cut up and stuck back together, allowing performances to be shortened, improved and composited. All of these properties were fully exploited by the early exponents of musique concrète, but pop and classical engineers were quick to see the potential too.

3: Machine learning

We don’t yet know how AI will change music, but it seems certain that it will. Already it’s possible to generate convincing pastiches of existing musical genres from a handful of prompts, to disassemble a recording into its constituent parts, and to have a machine‑learning‑based ‘intelligence’ mix or master our tracks. And the technology is very much in its infancy. Will AI lead to the end of music and recording as viable careers? Or will it prompt audiences to turn back to the real and embrace live music made by human beings again? Either way, Pandora’s Box has been opened, and there is no turning back.

2: Digital audio

In an analogue telephone system, multiple amplification or ‘repeater’ stages were required for long‑distance calls to offset signal loss. Each time the signal was amplified, the signal‑to‑noise ratio fell. In the 1930s, a British telephone engineer named Alec Reeves realised that the same problem did not apply to Morse code and other signalling techniques based on binary on/off states, because these could be perfectly reconstructed at any point as long as the signal was above the noise floor. Reeves came up with the idea of pulse code modulation (PCM): a means of encoding audio into on/off electrical pulses. The idea lay dormant for a number of years because no practical implementation was possible, but was revived during the Second World War when Bell Laboratories discovered the potential for transmitting encrypted signals. The eventual publication of their work after the war laid the foundation for digital audio as we know it, and the first practical digital audio recorder was developed by the Japanese broadcaster NHK in 1967.

The first practical implementation of pulse code modulation was the SIGSALY system, developed during WWII as a means of encrypting speech.

The first practical implementation of pulse code modulation was the SIGSALY system, developed during WWII as a means of encrypting speech.

1: Electrical recording

It is generally agreed that the first successful electrical recordings were released a century ago, in 1925. Prior to the invention of the condenser microphone and the vacuum tube amplifier, recording was a mechanical process. A horn transmitted air vibrations to a stylus, which scratched a trace into soft wax. The low fidelity of this process demanded difficult adjustments on behalf of the performers, who had to crowd round the recorder and play bizarre instruments like the Stroh violin.

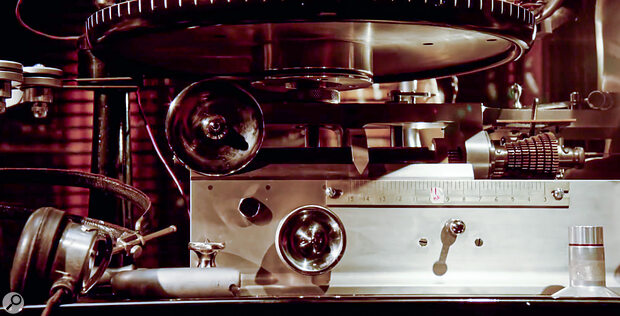

The original Western Electric recording system, with battery‑powered amplifiers and a gravity‑fed lathe, was transported around hotel rooms in the Southern USA to capture many now‑classic recordings. It has been meticulously rebuilt by Nick Berg at Endpoint Audio Labs in LA.

The original Western Electric recording system, with battery‑powered amplifiers and a gravity‑fed lathe, was transported around hotel rooms in the Southern USA to capture many now‑classic recordings. It has been meticulously rebuilt by Nick Berg at Endpoint Audio Labs in LA.

The Western Electric recording system, initially licensed to Victor and Columbia, did not change things overnight. The equipment was expensive, labels were cautious about audience acceptance, the Great Depression was in the offing, and electrical recording’s improvements in capture quality were not carried through to consumer playback systems. In the long run, however, this is surely the most fundamental step forward in the history of recorded music.