Placement in a movie trailer could bring up the lights on your library music career — but it ain’t easy.

Placement in a movie trailer could bring up the lights on your library music career — but it ain’t easy.

There’s a lot of money to be made writing music for movie trailers — so you have to be good. Have you got what it takes?

As we saw last month, Hollywood trailers are a glamorous and money-spinning corner of the library music world. Last month we looked at the Hollywood side: how the movie studios and trailer houses operate and what they are looking for in music. This month, we’ll look at the composer’s angle. How do you make trailer music, where does the money come from, and how do you get into the industry? As the owner of three trailer music labels under the Gothic Storm brand, with many major placements, this is a core part of my work and so I speak from some experience.

What Does Trailer Music Sound Like?

By definition, trailer music is whatever music is used in trailers; and a browse of www.trailers.apple.com will demonstrate the variety. Comedies typically use commercial, hip-hop or guitar-based tracks. Family adventures often have big orchestral themes. Fantasy epics might have choirs. Horrors might have creepy noises and massive scary slams. As we noted last month there are also constantly shifting trends: choirs and orchestras dominated five years ago, then pure sound design (impressive noises) reigned supreme, and lately it’s all about ‘trailerised’ cover versions and well-known songs, with epic booms, prowling electronica and orchestral elements augmenting the background for cinematic awe.

The Three-act Structure

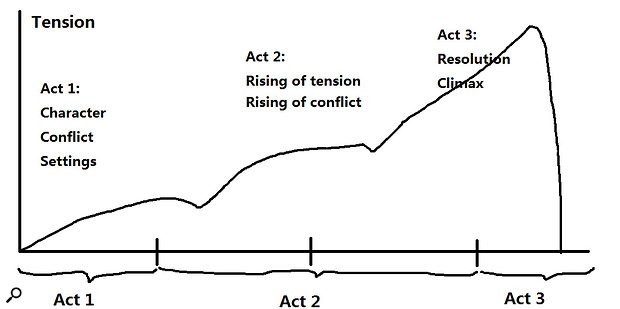

Underlying all this variety, one constant is the well-worn ‘three-act structure’: a compelling intro, a building main section and a massive ending. It’s a cliché and not universal, but the three-act structure remains a useful way to offer editors intros, middle sections and endings that they can either use as is, or edit together with different sections from different tracks. Gaps between sections are thus essential: pauses in the music make it easy for the editor to chop between different tracks at these edit points.

The ‘three-act structure’ is a universal theme of movie screenplays, and is equally important in the world of trailer music.

The ‘three-act structure’ is a universal theme of movie screenplays, and is equally important in the world of trailer music.

Trailer tracks will also typically have stunning sound design: whooshes, rises, sub-bass booms, intense impacts, power-downs and atmospheric noises that both hit the audience on a primal level of excitement or fear, and enormously help the editors by giving them incredible audio tools that they can synchronise with their cuts for maximum impact.

Trailer endings typically reach a huge climax but don’t resolve: they leave you hanging up in the air, to purposely create the feeling that the only true resolution is to go out and watch the film.

A great way to inspire yourself to write trailer music is to re-score an existing trailer.Although trends will always influence the choice of music, every film needs trailer music or sounds that are perfect only for that film. Choices are influenced by whether the film is serious or light-hearted, its era, location, whether it has multiple characters, is realistic or super-heroic and is emotional or action-heavy. For every possible variation there is a corresponding perfect musical tone, and for this reason, there will be an endless need for new trailer music and sound to fit endless new movie plots, however much you think there is nothing new under the sun.

A great way to inspire yourself to write trailer music is to re-score an existing trailer.Although trends will always influence the choice of music, every film needs trailer music or sounds that are perfect only for that film. Choices are influenced by whether the film is serious or light-hearted, its era, location, whether it has multiple characters, is realistic or super-heroic and is emotional or action-heavy. For every possible variation there is a corresponding perfect musical tone, and for this reason, there will be an endless need for new trailer music and sound to fit endless new movie plots, however much you think there is nothing new under the sun.

Writing Trailer Music

Just how do you make great trailer music? We asked some successful current trailer music composers and editors for helpful tips to get you started.

Greg Sweeney is music supervisor at LA trailer house Mob Scene.Re-score existing trailers. One piece of advice that came up repeatedly was to load an existing trailer video into your DAW with no audio, and create a new track to fit it. I’ve done this myself, and it forces you to think of the music as an expressive background to the on-screen action instead of following melodies and rhythms wherever they take you. Working to a good example of well-paced editing full of stops and dramatic builds creates well-crafted scaffolding for your track. As composer Chris Haigh tells us: “I sometimes compose over existing trailers, which works really well for developing different hit points.”

Greg Sweeney is music supervisor at LA trailer house Mob Scene.Re-score existing trailers. One piece of advice that came up repeatedly was to load an existing trailer video into your DAW with no audio, and create a new track to fit it. I’ve done this myself, and it forces you to think of the music as an expressive background to the on-screen action instead of following melodies and rhythms wherever they take you. Working to a good example of well-paced editing full of stops and dramatic builds creates well-crafted scaffolding for your track. As composer Chris Haigh tells us: “I sometimes compose over existing trailers, which works really well for developing different hit points.”

Greg Sweeney, music supervisor at the large LA trailer house Mob Scene advises: “Watch a lot of trailers and see what music and sounds are being used. Then turn down the music and re-score the trailer. There is a general formula to trailer music. The key is recognising that three-act structure and making it your own.”

Holly Williamson is the Vice President of Music at the LA trailer house Ignition Creative and owner/CEO of the music library Moon & Sun.Holly Williamson, Vice President of Music at the LA trailer house Ignition Creative and owner/CEO of Moon & Sun, a recently launched production music library and music supervision company, gives the same advice: “Pull up trailers on YouTube, turn down the volume and start writing music.”

Holly Williamson is the Vice President of Music at the LA trailer house Ignition Creative and owner/CEO of the music library Moon & Sun.Holly Williamson, Vice President of Music at the LA trailer house Ignition Creative and owner/CEO of Moon & Sun, a recently launched production music library and music supervision company, gives the same advice: “Pull up trailers on YouTube, turn down the volume and start writing music.”

Drop the templates. It can be tempting to collect your dream template of favourite sounds in the hope that it will massively speed up your writing process. As a writer, I personally discarded this method, finding it more inspiring and fresh to just load up sounds that you actually need for a specific piece of music. As writer Chris Haigh says, “I like to discover and create new sound palettes, be that pulsing synths, lots of different layered percussion elements or different layered-up string patches. I find it gives a slightly different sound to each track as I begin my process.”

Writer Cody Still also loads up sounds as he goes. “I load instruments as I work, placing each track into the appropriate track stack. I often start a new cue by experimenting with various synths to create a sound palette that I could develop a track around.”

Chris Haigh is a trailer-music composer working from Barnsley, England.Compare your track with the greats. Chris Haigh suggests A/B’ing your track against successful examples from the genre. “Try to be critical of your own work. We all finish a track and think ‘This is the most amazing piece of music ever written!’ until we listen the next morning and we are not so confident. But listen to other music in the style you are writing and put your track up against the best in the business and if you can’t honestly say your track sounds as good, if not better, then keep composing and improving.”

Chris Haigh is a trailer-music composer working from Barnsley, England.Compare your track with the greats. Chris Haigh suggests A/B’ing your track against successful examples from the genre. “Try to be critical of your own work. We all finish a track and think ‘This is the most amazing piece of music ever written!’ until we listen the next morning and we are not so confident. But listen to other music in the style you are writing and put your track up against the best in the business and if you can’t honestly say your track sounds as good, if not better, then keep composing and improving.”

Spectrasonics’ Omnisphere 2: a favourite of trailer composers the world over.Use great sounds. It’s essential that you’re using the best possible samples and soft synths. For example, while everyone has their preferences, almost every writer we spoke to mentioned the importance of Spectrasonics’ Omnisphere 2 in their work. It’s not hard to see why: it has good filters and effects, thousands of excellent, well-organised patches, which are easy to search and discover, and it’s pretty easy to program and customise, with thousands of excellent raw sound sources to work with.

Spectrasonics’ Omnisphere 2: a favourite of trailer composers the world over.Use great sounds. It’s essential that you’re using the best possible samples and soft synths. For example, while everyone has their preferences, almost every writer we spoke to mentioned the importance of Spectrasonics’ Omnisphere 2 in their work. It’s not hard to see why: it has good filters and effects, thousands of excellent, well-organised patches, which are easy to search and discover, and it’s pretty easy to program and customise, with thousands of excellent raw sound sources to work with.

Storage is cheap. Use it to stuff your computer with top-grade sample libraries.When it comes to orchestral samples, those most often mentioned were Cinesamples, EastWest’s Hollywood collection, LASS (LA Scoring Strings), Cinematic Strings and Cinematic Studio Series. Typically, writers will own all of the best collections and either layer them together or cherry-pick their favourite articulations from different libraries. A good example of this is Australian composer Mythix, who told us: “I would go to Cinebrass for horns, but Hollywood Brass for the ’bones, LASS2 for short strings and CSS for tremolo ensembles.”

Storage is cheap. Use it to stuff your computer with top-grade sample libraries.When it comes to orchestral samples, those most often mentioned were Cinesamples, EastWest’s Hollywood collection, LASS (LA Scoring Strings), Cinematic Strings and Cinematic Studio Series. Typically, writers will own all of the best collections and either layer them together or cherry-pick their favourite articulations from different libraries. A good example of this is Australian composer Mythix, who told us: “I would go to Cinebrass for horns, but Hollywood Brass for the ’bones, LASS2 for short strings and CSS for tremolo ensembles.”

For sound design, Kontakt developers Audio Imperia and my own company Gothic Instruments were cited as homes of great whooshes and bangs, while for effects and processing, FabFilter, UAD, Waves and SoundToys all proved popular.

Dylan Jones is a major LA-based trailer composer.Keep it simple. Composer Dylan Jones tells us that he’s “dumbed down” his writing since he began, but it’s important to note that he means doing more with less rather than making worse music! “When I first started writing trailer music, I made the mistake of focusing too much on melody. That’s good for plenty of other things, but not for trailer music. Over time I would say I ‘dumbed down’ my music. As offensive as that might sound to some people, I often see it as a challenge that only great writers can master; that is, making your music ‘dumb’. I’ve learned that, more than anything, trailer music is formulaic. You have to find the perfect balance of simplicity, but keep it interesting and progressive enough to warrant being used to grab the audience’s attention, all while never getting in the way of what dialogue and other sound effects might be in the cut of the trailer. This ‘dumbing down’ of my writing style has been the most difficult hurdle to pass for me.”

Dylan Jones is a major LA-based trailer composer.Keep it simple. Composer Dylan Jones tells us that he’s “dumbed down” his writing since he began, but it’s important to note that he means doing more with less rather than making worse music! “When I first started writing trailer music, I made the mistake of focusing too much on melody. That’s good for plenty of other things, but not for trailer music. Over time I would say I ‘dumbed down’ my music. As offensive as that might sound to some people, I often see it as a challenge that only great writers can master; that is, making your music ‘dumb’. I’ve learned that, more than anything, trailer music is formulaic. You have to find the perfect balance of simplicity, but keep it interesting and progressive enough to warrant being used to grab the audience’s attention, all while never getting in the way of what dialogue and other sound effects might be in the cut of the trailer. This ‘dumbing down’ of my writing style has been the most difficult hurdle to pass for me.”

Cody Still is a US trailer music composer.US composer Cody Still agrees that deceptive simplicity is at the heart of the art. “Trailer music is often very simplistic from a music theory perspective. The simplicity of trailer music, however, is highly deceptive, causing many composers to think that trailer music is easy to create. It requires immense production skills in order to be competitive.”

Cody Still is a US trailer music composer.US composer Cody Still agrees that deceptive simplicity is at the heart of the art. “Trailer music is often very simplistic from a music theory perspective. The simplicity of trailer music, however, is highly deceptive, causing many composers to think that trailer music is easy to create. It requires immense production skills in order to be competitive.”

Production quality is everything. As a publisher, I hear lots of underwhelming demos every day. The ones that stand out are those with a truly great production: highly realistic orchestral mock-ups, brilliant sounds, great percussion, great mixing and great sound design. There is also the emotional message that world-class productions convey: ‘This is massive and amazing!’ If a Beethoven piece was arranged on bad orchestral samples with weak drums by a 12-year old in GarageBand then dropped into blockbuster trailer in an IMAX multiplex, people would think ‘What is this shit?’ By contrast, a few tense orchestral notes in a world-class maelstrom of drops, rises, anti-phased screams and thunderous percussion excites the masses at a gut level. This isn’t ‘dumbing down’ so much as putting emotional impact first and everything else second.

Trailer music is not the place to show off your maximalist avant-garde composition skills — usually.As writer Chris Haigh tells us, “I think production is a massive key part of today’s trailer music sound. I think maybe even more than the composition itself. Creating unique amazing sounds for your tracks is crucial. Some of the production quality that is being used in trailer music is absolutely world-class.”

Trailer music is not the place to show off your maximalist avant-garde composition skills — usually.As writer Chris Haigh tells us, “I think production is a massive key part of today’s trailer music sound. I think maybe even more than the composition itself. Creating unique amazing sounds for your tracks is crucial. Some of the production quality that is being used in trailer music is absolutely world-class.”

Dylan Jones agrees: “Production skills are highly essential. Because trailers rely so heavily on music and sound design, these things always need to sound top of the line, better than television or film scores. And even after you finish writing, you will spend more time making sure everything sounds as good as it can. These days I find myself spending about 20-30 percent of my time on composing, and the rest of the time working on production and mixing. You also absolutely need to be able to make orchestral samples sound as real and over-the-top as possible for trailers.”

Composer Cody Still reiterates the primacy of production over everything else: “I would place production skills at the very top of the list as being most important. Conversely, I would place theory and scoring skills closer to the bottom of the list.”

Mark Petrie is a US trailer music composer.Give it weight. Composer Mark Petrie puts his finger on what makes trailer music trailer music: a kind of weighty, epic seriousness. “Anything good and ‘trailer-ish’ can be used on TV, but I think there’s a feeling — a massive amount of gravitas — that trailer music needs to possess in order to feel right at home in a trailer. It’s that authenticity to the ‘feel’ of trailers that gets tracks licensed.”

Mark Petrie is a US trailer music composer.Give it weight. Composer Mark Petrie puts his finger on what makes trailer music trailer music: a kind of weighty, epic seriousness. “Anything good and ‘trailer-ish’ can be used on TV, but I think there’s a feeling — a massive amount of gravitas — that trailer music needs to possess in order to feel right at home in a trailer. It’s that authenticity to the ‘feel’ of trailers that gets tracks licensed.”

Watch other trailers for inspiration. Watching existing recent trailers is a great way to understand what the trailer editors and studios are looking for. You can be sure that everything you see in existing big-budget trailers has been chosen in a remorseless competitive environment, with millions of dollars of marketing budget and potential revenue resting partly on that choice of track. That’s not to say the best track wins every time — there will always be baffling decisions at the top — but this approach certainly beats guesswork or listening to tracks that never made the grade.

Be original. Although you need to learn the ‘rules’ and keep a close eye on current trends, your own tracks’ chances of being used are increased if you can add a spark of originality: something special, a ‘signature sound’ not found anywhere else. As writer Dylan Jones puts it: “A lot of trailer music sounds very similar, and I think true creativity and innovation is something that is very necessary these days, as the market seems to be getting pretty tired of that basic trailer sound. Innovate, sound different, all while still not going too crazy, and you will find at least some success.”

Conor Aspell is music supervisor at LA trailer house Vibe Creative.Conor Aspell, music supervisor at LA trailer house Vibe Creative, wants to be surprised: “Try something weird and wild. I really like it when I’m listening to a cue and involuntarily yell ‘Woah, whaaat?’”

Conor Aspell is music supervisor at LA trailer house Vibe Creative.Conor Aspell, music supervisor at LA trailer house Vibe Creative, wants to be surprised: “Try something weird and wild. I really like it when I’m listening to a cue and involuntarily yell ‘Woah, whaaat?’”

Where The Money Comes From

Trailer music money is paid by the movie studio (Paramount, Lucasfilm, Twentieth Century Fox and so on) to the trailer music publisher in return for a synchronisation (‘sync’) licence, ie. a license to synchronise your music to their trailer. Then the publisher typically pays the composer 50 percent of that as a royalty. This royalty rate will vary depending on your deal; perhaps it was a buy-out and you get no royalties, or your publisher is selling through an agent who takes 50 percent first.

Amounts vary. Custom-created cues for blockbuster theatrical trailers (‘theatrical’ being the main trailer in cinemas worldwide, also known as the ‘official’ trailer you’ll find on YouTube) can command $100,000 or more. This can go down to the hundreds for very short bits of sound design used in TV trailers on lower-budget movies. The most successful custom trailer composers can earn over $1 million per year. Library composers will generally see much less because of lower fees and number of placements, but this is somewhat made up for by non-trailer income from the same music, of which more later.

Custom Shops

Many of the biggest theatrical trailers have their music custom-created, and therefore don’t use library music. The majority of these jobs go to a small number of specialist composers with incredible production skills who live in LA and have worked hard to build trust and great working relationships with trailer house music supervisors. It’s not impossible to work your way in if you’re in LA — the right demos to the right people at the right time will help — but it’s more difficult than placing tracks with a library music label.

Jeff Fayman is a co-founder of Immediate Music, one of the first trailer music companies.Trailer library music labels will also invite their best, fastest and most reliable composers to pitch for the custom jobs that they hear about. These make great money if you land the placement, but, as ever, you will be up against hundreds of other composers, so you need to have the perfect music at the perfect time, and the odds are against you unless everything you do is utterly amazing.

Jeff Fayman is a co-founder of Immediate Music, one of the first trailer music companies.Trailer library music labels will also invite their best, fastest and most reliable composers to pitch for the custom jobs that they hear about. These make great money if you land the placement, but, as ever, you will be up against hundreds of other composers, so you need to have the perfect music at the perfect time, and the odds are against you unless everything you do is utterly amazing.

Trailer Libraries

If you want to approach trailer music libraries, my personal advice is to be so amazing that publishers only ever hear demos that are as good or better than the best trailer writers alive. Send them to all the best companies with polite persistence until they listen and accept you, or at least send you away with good advice. Jeff Fayman at the legendary trailer library Immediate Music offers a touch of hope: “Right now we have an abundance and are only considering a small amount, if at all. But great music will eventually get heard and rise to the top of the pack.”

Mikkel Heimbürger at Colossal Trailer Music remains open to greatness: “Send me a couple of tracks, not 25, and if you’re a great writer it’s a done deal. Seriously, sometimes it can be that easy.”

Mikkel Heimbürger is a composer of trailer music.I echo Mikkel’s sentiment: I’m forever saying “we have no space for new writers”, but the minute I hear something truly amazing which both understands the genre but sounds original, I want to grab it and release it quick before anyone else.

Mikkel Heimbürger is a composer of trailer music.I echo Mikkel’s sentiment: I’m forever saying “we have no space for new writers”, but the minute I hear something truly amazing which both understands the genre but sounds original, I want to grab it and release it quick before anyone else.

On The Down Side...

Now that you’ve learned tips from the greats and are ready to sing hi-ho and march off to Hollywood to collect your millions, it’s time to point out some of the negatives of the trailer music business.

Snobs will hate you. Film and orchestral music buffs look down at trailer music as if it is the ultimate debasement of culture. Relative to the rest of library music, it’s pretty cool and glamorous, but every trailer writer has to listen to insults from ignorant snobs from time to time.

If you’re going to be a successful writer of trailer music, you’ll have to learn to put up with the sneers of purists. The fact that you will be earning a lot more money than they are might help with this.However, established trailer writers tend to see this as partly justified. Mark Petrie tells us: “In some ways it’s warranted. It drives me a little nuts how we hear the same old I minor to flat VI major used over and over again, the same short strings going back and forth between I and flat III... we could definitely do with some more musical innovation and sophistication. That said, where trailer music is at the cutting edge of innovation is in the production.”

If you’re going to be a successful writer of trailer music, you’ll have to learn to put up with the sneers of purists. The fact that you will be earning a lot more money than they are might help with this.However, established trailer writers tend to see this as partly justified. Mark Petrie tells us: “In some ways it’s warranted. It drives me a little nuts how we hear the same old I minor to flat VI major used over and over again, the same short strings going back and forth between I and flat III... we could definitely do with some more musical innovation and sophistication. That said, where trailer music is at the cutting edge of innovation is in the production.”

Dylan Jones takes a similar line: “Trailer music is simple. It’s the pop music of the classical world. But that doesn’t mean it’s easy. Your production and sound design need to be top-notch, you need to keep up with market trends, you need to constantly innovate, you have to be able to craft tracks that are simple enough to fit into a trailer, yet creative and progressive enough to captivate an audience and drag them into the picture.”

Beyond affronts to your artistic worth, worse awaits.

It’s hard to sign your tracks to publishers. As a trailer music publisher, I get composer demos every day, and sometimes I’m just too busy to listen. When I do, the quality is usually just average: it sounds OK, just not great. Since I and all other good trailer music libraries already have plenty of great writers, your music has to sound truly special for owners to jump on it. That ‘specialness’ involves showing that you deeply understand the genre, have amazing production skills and, on top of that, offer something with an original character.

Agus Gonzalez-Lancharro owns trailer library Really Slow MotionYou have only a tiny chance of actually landing a trailer. Let’s say you’ve got over the snobbery and got some tracks placed with publishers. The next unlikelihood is actually getting your music used in a trailer. Agus Gonz lez-Lancharro, owner of trailer library Really Slow Motion, gifts us a reproductive metaphor: “I sometimes use the metaphor of placements as being like human conception. All those millions of vigorous spermatozoons trying to make it to the ovule first, and once the very one makes it there, it still needs to go through nine months of adventures to eventually see the outer world.”

Agus Gonzalez-Lancharro owns trailer library Really Slow MotionYou have only a tiny chance of actually landing a trailer. Let’s say you’ve got over the snobbery and got some tracks placed with publishers. The next unlikelihood is actually getting your music used in a trailer. Agus Gonz lez-Lancharro, owner of trailer library Really Slow Motion, gifts us a reproductive metaphor: “I sometimes use the metaphor of placements as being like human conception. All those millions of vigorous spermatozoons trying to make it to the ovule first, and once the very one makes it there, it still needs to go through nine months of adventures to eventually see the outer world.”

In numbers, about 100 decent-budget films per year use library tracks, and there are roughly 20 good trailer music publishers, each with 10,000 tracks. That means there are 200,000 tracks trying to land on 100 films. So, your track has a one in 2000 chance of landing on a trailer. And every week new music is released, making the odds ever more remote.

On the bright side, every film actually has many trailer versions: TV spots, online, behind-the-scenes featurettes and international versions. Also, if you do pure sound design, up to 90 cues can end up in one trailer campaign, increasing your odds. And, if you’re amazing and your publisher is working very hard at sales and building personal relationships with editors and music supervisors, that will help your chances further. Still, the realistic odds of most composers landing a particular library track on a particular film trailer are very small. The frank truth is that most ‘trailer tracks’ released by most ‘trailer music’ companies will never be used on a trailer.

Australian composer Mythix.You have to wait a long time to get paid. Another downer is that payment might not filter through to you until three years after the music was initially chosen. This is because payment is held back until the film has left cinemas, and slow payment departments of the major studios can add extra months. Finally, standard library publishers will typically only pay out writer royalties twice a year, adding a further delay. Sometimes, you just never get paid. The studio might use a track, make a genuine error in losing their records of doing so, and you might never find out. It happens!

Australian composer Mythix.You have to wait a long time to get paid. Another downer is that payment might not filter through to you until three years after the music was initially chosen. This is because payment is held back until the film has left cinemas, and slow payment departments of the major studios can add extra months. Finally, standard library publishers will typically only pay out writer royalties twice a year, adding a further delay. Sometimes, you just never get paid. The studio might use a track, make a genuine error in losing their records of doing so, and you might never find out. It happens!

Income Outside Trailers

Luckily, there are alternative sources of income that provide a safety net even if you happen not to land the big blockbusters. Most people wouldn’t guess that although my Gothic Storm label specialises in trailer music and has a Hollywood office, Hollywood placements only actually account for around 30 percent of our income. The remaining 70 percent comes from elsewhere.

Non-Hollywood sources of ‘trailer music’ income are: worldwide TV, worldwide film trailers, YouTube streaming and fan sales. The latter now come mainly from Spotify streaming, which has overtaken Apple income. Worldwide TV can be very good for ‘trailer music’ because the styles suit TV promos — trailers for upcoming TV shows — and sports. Roughly 45 percent of our income is from worldwide TV. As for worldwide film trailers, there is a healthy market in South Korea and China for big-budget homegrown films, and roughly 10 percent of our income comes from international trailers.

Epic Music Vs Trailer Music

Beethoven was perhaps the greatest composer who ever lived, but would he have had the production chops to make it in the world of trailer music?Finally, we should not forget that ‘epic music’ has lots of fans in its own right, who generate about 15 percent of our revenue through YouTube, Spotify, Apple and other sources. On YouTube, if you or your publisher are registered with a ‘ContentID partner’ such as AdRev or EMVN, then if your track is used without permission, the system recognises it and diverts advertising revenue your way. A rule of thumb (which varies) is that you can earn $1 per 1000 views this way; not bad when view counts get into the millions, which they can.

Beethoven was perhaps the greatest composer who ever lived, but would he have had the production chops to make it in the world of trailer music?Finally, we should not forget that ‘epic music’ has lots of fans in its own right, who generate about 15 percent of our revenue through YouTube, Spotify, Apple and other sources. On YouTube, if you or your publisher are registered with a ‘ContentID partner’ such as AdRev or EMVN, then if your track is used without permission, the system recognises it and diverts advertising revenue your way. A rule of thumb (which varies) is that you can earn $1 per 1000 views this way; not bad when view counts get into the millions, which they can.

Several large YouTube channels with over 400,000 subscribers such as Epic Music VN (Vietnam), Epic Music World and Trailer Music World dominate the scene, with epic music set to fantasy graphics or scenes from films and games. The fan base is big in the USA but is also truly international, particularly in Vietnam and wherever people (especially young men) spend serious hours on video games.

However, ‘epic music’ is a specific style, involving big percussion, orchestras, choirs and much gravitas. Carl Orff’s 1935 ‘O Fortuna’ from Carmina Burana, well known as the theme from The Omen and in the UK as the music from ’70s Old Spice adverts, is a good early example of the epic style now common in fantasy games and films.

There was a time, from roughly 2000 to 2014, when a lot of trailer music was also epic music. In that now-passed golden age, composers of trailer music became beloved of fans on forums and YouTube channels. However, the two strands branched apart in an epic schism from 2014, as trailer music became much more about sound design and then hit songs, leaving ‘epic music’ weakened without the big trailer dollars being pumped into productions. Whereas Bergersen’s Two Steps From Hell took the fan-friendly ‘epic music’ branch in the great trailer/epic split, the other trailer library companies largely followed the more dependable trailer route of making whatever the Hollywood studios wanted, even if it was walls of booms and noise under whispery cover versions.

Epic music fan Gabriel Lago.Although my company has seen steady growth in fan-based income, Do San Thanh, who runs the Epic Music VN YouTube channel, explains that all is not well after the split between trailer and epic music: “Epic music has slowed down recently. The peak was 2012-2014. The problem recently is a lack of real high-quality tracks made purely for fans. Most trailer music publishers cannot survive with fan sales, so they create music for the trailer industry first, with most tracks not really fit for public listening.”

Epic music fan Gabriel Lago.Although my company has seen steady growth in fan-based income, Do San Thanh, who runs the Epic Music VN YouTube channel, explains that all is not well after the split between trailer and epic music: “Epic music has slowed down recently. The peak was 2012-2014. The problem recently is a lack of real high-quality tracks made purely for fans. Most trailer music publishers cannot survive with fan sales, so they create music for the trailer industry first, with most tracks not really fit for public listening.”

Not fit for public listening, indeed! Some of us quite like subwoofers shaking our bowels.

Let’s remind ourselves why people love this music by hearing from some real epic music fans who follow our Gothic Storm Facebook page. Gabriel Lago is from Londrina, Brazil and told us: “I started in the epic music world when I found some songs of Immediate Music. I fell in love immediately and started searching for other composers. I like Two Steps From Hell, Dirk Ehlert, Ivan Torrent, Audiomachine etc... and, of course, Gothic Storm Music! I love to listen to epic music while I drive, write and do the chores. You guys rock!”

Sharwin Kailashi is an epic music fan and aspiring music producer from Mumbai, India.Sharwin Kailashi is an epic music fan and aspiring music producer from Mumbai, India: “For me epic music is something that defines the true sense of music. The ability to make you feel those emotions just by sounds is what makes it absolutely outstanding. I was always very intrigued and mesmerised how that music behind a particular scene made it so appealing to me. And how certain pieces invoke emotions within me. There is so much more to it. Exploration is the word!”

Sharwin Kailashi is an epic music fan and aspiring music producer from Mumbai, India.Sharwin Kailashi is an epic music fan and aspiring music producer from Mumbai, India: “For me epic music is something that defines the true sense of music. The ability to make you feel those emotions just by sounds is what makes it absolutely outstanding. I was always very intrigued and mesmerised how that music behind a particular scene made it so appealing to me. And how certain pieces invoke emotions within me. There is so much more to it. Exploration is the word!”

Epic Finale

In this two-part look at trailer music, we’ve seen how Hollywood trailer music began in the 1970s and developed, how the system works, how to find work, how to make the music, how much money can be made, how styles have changed, and how income from outside of Hollywood can provide a safety net for composers of the genre. However, the question of whether this is a great option for your composing career is a tough one. The competition is fierce, the production quality is very hard to match and the opportunities to get tracks placed are scarce. And yet, if you truly love trailers and trailer music with all your heart, and your affinity is so overwhelming that you have no choice, then you have a pretty good chance of cracking it if you work hard and long enough.

If you don’t like risk and you like other forms of music just as much, you’re probably best off only dipping your toes in the water while seeking your library music fortune elsewhere, in the gentler and more dependable backwaters of worldwide TV and advertising. If you actually want to be adored as the next Thomas Bergersen, making heartfelt epic music for epic music lovers, then remember what Do San Thanh has told us, that the epic music world is in a lull because there isn’t enough great epic music for fans to fall in love with all over again. Perhaps you could be the next epic Messiah to lead a million Vietnamese fans over the snow-capped volcanoes of YouTube, and unite the trailer and epic factions once more, placing the love of grandiose choirs back in the gnarled hearts of Hollywood and ushering in a new Golden Age, like once we had and so cruelly lost back in 2014. Epic dreamer, awaken: you may be our only hope!

All About Library Music: Part 1 Getting Started

All About Library Music: Part 2 The Business

All About Library Music: Part 3 The Composer

All About Library Music: Part 4 The Client

All About Library Music: Part 5 Networking

All About Library Music: Part 6 Hollywood Trailers

All About Library Music: Part 7 How To Write Trailer Music

Alessandro Camnasio: The Art Of Sound Design

Milan-based Alessandro Camnasio has been the main sound designer of my Gothic Storm’s Toolworks label for the last few years. He’s also the main sound designer with my Gothic Instruments software company, which makes the Sculptor and Dronar series for Kontakt. I asked him some questions about his craft.

Milan-based Alessandro Camnasio has been the main sound designer of my Gothic Storm’s Toolworks label for the last few years. He’s also the main sound designer with my Gothic Instruments software company, which makes the Sculptor and Dronar series for Kontakt. I asked him some questions about his craft.

How did you get started making Hollywood trailer sound design?

In late 2010 a music library from Los Angeles came across some experimental samples and demos I created and asked me to write some sound design-oriented tracks for them.

Did you realise that sound design would be so popular in movie trailers?

Not at all! To be honest, I didn’t know a thing about trailers and how they were made, since I came from academic studies in composition and electroacoustic music at the Conservatory.

Are the skills needed for trailer sound design the same as music production or very different? What kind of techniques do you use?

For creating trailer sound design, you certainly need to have very good skills in processing, recording, synthesis, mixing and mastering. Personally, I found that having some notions in music theory, harmony, acoustics or knowing something about musical instruments, could be very helpful, even when you are trying to create a new sound. So there’s not much distance between sound design and music production in terms of basic skills.

Why do you create original sound design when you could use sample libraries like a lot of other ‘sound designers’?

There are many reasons. Firstly, I see sound design as the last frontier for the composer. The ‘composition of sound’ and the possibility to create sounds that nobody has ever heard is quite fascinating to me. The whole process is interesting and fun at the same time, because it also gives me the chance to learn many things about the topics that are or could be connected with a specific sound design project. Secondly, I believe that if you do your research and create things from the ground up, you will have more chances to stand out with your own voice. Last but not least, many developers have a licence agreement that does not allow the creation of single sounds from their content. I have a very broad concept of what’s music. I often find myself listening to the sounds that surrounds me with the same interest I would put when listening to a piece of music. Basically I find music everywhere.

What advice would you give to a new sound designer wanting to place tracks in Hollywood trailers?

I’d say, try to leverage your background and build from that. Be curious and learn at least a new thing each day about what you are trying to achieve. Listen to what others are doing, watch trailers, analyse and try to understand the logic behind certain things and why they work or not. Be persistent, take constructive criticism from people that know their craft because it’s pure gold, try to be your hardest critic but not to the point of being stuck: finish what you are doing at the best of your possibilities. It won’t be perfect, but the good news is that you can improve your craft the next day by doing another thing that probably will be better. Give yourself the chance to experiment, to make mistakes, to try again and improve. Most importantly, enjoy what you are doing, enjoy the process. Get fully involved in what you are doing to the point of really having fun: it’s the only way to do great work.

Thomas Bergesen: Master Of Epic Music

Striding like a colossus across the epic music world is the composer Thomas Bergersen, a member of the duo Two Steps From Hell — who, as Quantum Leap, are also a large sample library developer in a collaboration with EastWest. A regular topper of worldwide classical music charts with millions of fans, Bergersen began as a trailer music composer but left it behind to make the music he wanted to make. It’s still used on trailers, but is written for the love of it and for the fans.

Striding like a colossus across the epic music world is the composer Thomas Bergersen, a member of the duo Two Steps From Hell — who, as Quantum Leap, are also a large sample library developer in a collaboration with EastWest. A regular topper of worldwide classical music charts with millions of fans, Bergersen began as a trailer music composer but left it behind to make the music he wanted to make. It’s still used on trailers, but is written for the love of it and for the fans.

As Do San Thanh, owner of the Epic Music VN YouTube channel, explains: “Most epic music comes from films, trailers, games... but the truly epic music comes from Two Steps From Hell in my opinion. Thomas Bergersen created the foundation for the whole epic music genre.” So we caught up with the man himself, now at work on new music.

When did you realise that you’d found a massive extra career in being an epic music artist with fans and record sales?

It was always art over business for me. When an underground community started surfacing on YouTube and other musicians were cracking down on it and removing their material, I thought it made more sense to let it flourish and maybe gain a bigger audience.

Your target market? Epic music is a popular genre in its own right, particularly among young men with a penchant for video games.Have you consciously moved away from trailers to write music for purely artistic reasons?

Your target market? Epic music is a popular genre in its own right, particularly among young men with a penchant for video games.Have you consciously moved away from trailers to write music for purely artistic reasons?

Believe it or not, I never really set out to write trailer music. I’ve just written music I enjoy, and that happened to go well with trailers so we made sure the industry was aware of the music. I always gravitated towards music that was larger than life and dramatic in nature.

Do you have any advice for trailer and epic music composers?

Write the music you love to write, not the music you think others want. I don’t believe in forcing anything that doesn’t come naturally to you.