Library music publishers: fat cats growing rich off the work of others, or selfless individuals who will go out of their way to help you succeed?

Library music publishers: fat cats growing rich off the work of others, or selfless individuals who will go out of their way to help you succeed?

Composers need publishers. But are they there to help us, or help themselves?

This series has given you an inside perspective on the opaque world of library music and helped to clarify many questions. What music should you write? (Authentic, minimal and upbeat music.) Who should you send it to? (Library publishers.) How much will you get paid? (Lots, if you write a lot and make it good.) And when will you start to see royalties? (From three years after the music is released.)

A repeating theme has been the importance of the library music publisher, that powerful gatekeeper who either guides you onto the glittering path or ignores your demos and leaves you watching your life clock. The publishers’ importance comes from their key role as quality filters, organisers and salespeople, standing between you, the composer, and the large clients such as ad agencies and TV production companies who pay publishers to use the music.

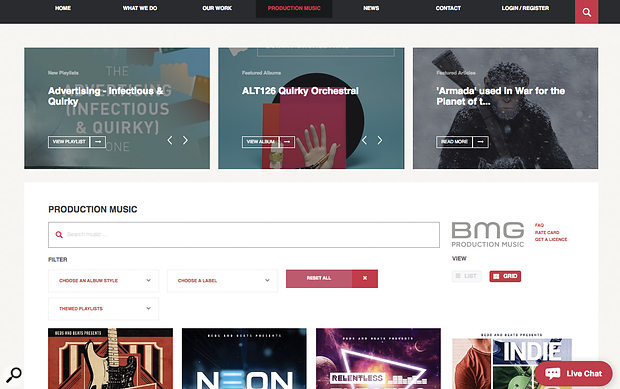

This month we take a closer look at the world of the publisher to find out what makes them tick. As a library publisher myself, I’ll offer my own inside view, alongside interviews with a pair of Vice Presidents at the major BMG Production Music and the co-owner of a strong independent New York publisher, Video Helper. Once you have a better understanding of the publisher’s work and needs, perhaps you’ll have a better chance of finding work with them.

Us Vs Them?

So, who are these Dickensian publisher overlords, growing fat from your toil in gilded offices and jetting around the world while mocking your humble begging emails and plotting to reduce your royalties?

Some composers really do have this impression of library publishers. As a composer-publisher I’ve read these complaints in forums and occasionally stuck my oar in, but hopefully this article will help to mend a bit of this mistrust. That said, before we break into a hymn to the publishing world’s selfless saviours, I have certainly heard statements from publishers like “Why not just remove the writer’s share of sync royalties?” and “Never invite writers to a party, they’ll just hassle you for work.” I’ve also heard publishers vow to never hire some poor writer again just because they were new, didn’t understand the rules and committed some sin or other out of ignorance, such as asking for a royalty split that no-one would agree to, sharing their tracks on YouTube before they were released or handing in ‘unmastered’ mixes with bus compression on. So yes, some library publishers can be mean, but thankfully most are pretty OK.

What Do Publishers Want?

Whether it’s human nature or capitalist sickness, most publishers want more money. Better business income means hiring more staff to take away various burdens, recording more premium albums at Abbey Road, paying for advertising, and gaining brand prestige by sponsoring events. Better personal income means more financial security, a nicer house, nicer car, nicer holidays, better clothes, and so on. Some humans, either through spiritual enlightenment or temperament, have stepped off this acquisitive cycle and learned to put more wholesome things first, but most library publishers have not. Like you, publishers would prefer having more money to less, because they can spend it on things that they want. You can help library publishers to have more money by writing music that sounds amazing and perfect for the market: an easy sell for them, which will help them earn more dough for their company and themselves. The more pound signs they can hear in your music, the faster they will take it.

Publishers also like to save money. There are some big spenders, and maintaining quality is always important, but most publishers big and small have a degree of budget-consciousness. So if you can offer them an album of amazing live performances where you have covered the recording costs, you could jump straight to the front of the release queue. In an ideal world, of course, they should pay; but an investment in your own talent could help get your albums placed more easily. Conversely, if you cost the publishers more money than everyone else with your lavish requirements, you will have to be pretty amazing to keep them on board.

Nothing irks a library music publisher more than discovering a gap in their catalogue where music ought to be. To the composer, that represents an opportunity...

Nothing irks a library music publisher more than discovering a gap in their catalogue where music ought to be. To the composer, that represents an opportunity...

Also high on publishers’ lists of priorities is filling gaps. Library publishers need to be able to respond quickly to search requests where clients suddenly need a track at short notice to fit a particular brief, perhaps because they’ve discovered at the last minute that a big artist won’t allow their own track to be used. From personal experience, I can attest to the frustration of realising that, despite offering thousands of tracks, our company has nothing that fits a particular request.

For example, we were asked recently if we had a sweeping epic orchestral track full of mystery that felt like a big event, for a new murder mystery movie trailer. The answer was “Not really.” And so, that big sweeping mystery album we didn’t have went straight onto our to-do list. We want to fill gaps because we want to be the beloved go-to guys who always have what the client needs. As well as our insecurities about having something missing, publishers also have a collectors’ instinct, wanting a nice full set of styles sitting proudly on the shelf.

As a composer, you can help to solve the publisher’s gap-insecurity. Most publishers place their catalogues online where they can easily be searched and auditioned, so if there are gaps, it’s not hard to find them. Send them music they don’t already have, tell them you’ve noticed a gap in their catalogue and can help them fill it. This is an easier task with newer, smaller labels who have bigger gaps, but even large catalogues will also always have niches to fill. They might have happy banjos, but do they have happy banjos with bells on?

Time Is Money

Publishers are also happy when they can get more work done. Even the major library publishers are typically small teams, meaning that every extra staff hire burns a relatively big hole in their budgets. This means that time is a precious commodity to them, so instead of being someone who takes up lots of it by constantly phoning or emailing with naïve questions that you could look up on Google or post on composer forums, be someone who does as much as possible for them. Offer them a complete no-brainer amazing album that will make them money and fill a gap. Give the tracks great titles so they don’t have to. Follow their instructions and change requests carefully so they don’t have to waste time repeating them to you. Offer to write your own track descriptions and key words for the metadata. If there’s a problem during the production of an album, suggest solutions instead of waiting for them to come up with ideas. Be a help, not a burden, and they will feel good towards you and keep you on board for more work.

Publishers like to win. Us library publishers can start out as sharing hippies, but once newcomer rivals take away our customers, former employees set up rival companies and we narrowly miss out on a few big placements, it’s hard not to get bitten by competition madness. Perhaps you understand, because composers have their analogue: being frustrated by missed opportunities and feeling compelled to post ‘placement news’ on social media that only other competing composers read, more out of insecurity and envy than gloating. At conferences, library publishers are buddies with a shared experience, but by day, they are enemy marauders always trying to pull a fast one — or so it can feel.

The fact that publishers are locked into a pervasive struggle for superiority means that if your music has something their rivals don’t have, that could fire a few competition neurones and make their reptile brains want to grab it. Also, if they love your music already and you offer to only write library music for them, they might agree to take more new music from you out of a desire to build a loyal army to destroy their enemies.

A down side of publisher competitiveness is that you ought to be careful how you talk to them about their rivals. If you’re too glowing about their competitors, or offer music which you admit has been rejected by someone else, a highly competitive big-baby publisher will feel insulted and not like you, because you made them feel bad.

Despite everything, though, publishers generally want to help composers. It’s in their interests to improve your financial security and ensure that you continue to deliver good material, so they will reward your hard work and talent if they possibly can. So don’t be afraid to ask them for advice from time to time if something is troubling you or you’re curious. Also, if you’re extremely good but extremely poor and need money for basic gear upgrades, even if they don’t usually give advances, try politely asking anyway, backed up by an honest explanation of why you need the money. Many smaller publishers would be crippled if they had to give generous advances and fees to everyone, but all of them can make an exception for a deserving case.

Most library publishers also enjoy the sense of working as a team with you, their co-workers and clients, all pulling together towards the common goal of getting great music placed on great video productions. So be a good team player. Cooperate, find your special role, and keep in mind the bigger picture of everyone working together to achieve great results, rather than just being grumpy about your grievances. That said, airing your worries can sometimes be good for trust and team building too.

Open Season

Hopefully, now that you’ve peered into the money-hungry, penny-pinching, gap-insecure, overworked yet composer-friendly team-player minds of library music publishers, you’ll have a better grasp of how to approach these delicate flowers. Treat us as oddballs to be friendly to, rather than anonymous email addresses to place your music with.

Two social media groups that you should be part of are SCOREcast (top) and Perspective.

Two social media groups that you should be part of are SCOREcast (top) and Perspective.

Time for some questions! We will start with my questions, to be followed up by queries from members of two Facebook groups you should join: SCOREcast London and Perspective: A forum for film, TV and media composers. Our publisher interviewees are Paul Gulmans (Vice President for BMG Production Music Netherlands & Germany), John Clifford (Senior Vice President for BMG Production Music UK) and Stewart Winter (co-owner of New York independent library publisher Video Helper). Alongside their illuminating responses, I’ll add my own viewpoints and composer takeaways to help you get the best from these answers.

- What’s special about your company?

Stewart Winter (Video Helper): “We specialise in a library that addresses short form promotional/branding work, like promos, trailers and commercials. Stuff that’s more active and meant to be used in shorter, denser spots.”

Like many independent libraries, Video Helper specialise in a particular niche within the production music business.

Like many independent libraries, Video Helper specialise in a particular niche within the production music business.

John Clifford (BMG PM UK): “BMG is The New Music Company. We are the new major in production music, determined to do it better and differently to the others. We are establishing a first-rate catalogue, best-in-class delivery system and global footprint in all major markets employing production music entrepreneurs whose experience and knowledge of the business is unrivalled.”

BMG Production Music are among the ‘heavy hitters’ of the industry.

BMG Production Music are among the ‘heavy hitters’ of the industry.

Composer takeaway: Note that, like many independents (including my labels), Video Helper have their own niche musical style. This is something to take into account before sending targeted demos. BMG Production Music are more about size, reach and speed, but note that they employ entrepreneurs — in other words, their offices are run by people who started out building independent labels, perhaps making them more approachable and energetic than the established company name might suggest. Every company is different, so keep learning about who you are writing to, and tailor your communications and submissions towards what particularly inspires them.

- What’s your story? What did you do before getting into publishing, and how did you get where you are?

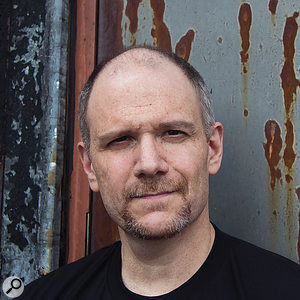

John Clifford of BMG Production Music UK.John Clifford (BMG PM UK): “For me there is no ‘before’! I’ve worked in the production music business for my entire career to date (25 years). In the beginning, I had no idea what production music even was, but as a young person simply wanting to get started in the music industry, I was given the opportunity of my first ‘real’ job and I started at the age of 18 working for an independent production music publisher called Nightlight Music in Sydney, Australia. Almost five years later, I joined Zomba Production Music as an Account Manager and not long after that became Head of Marketing. BMG subsequently acquired Zomba, and in mid-2005 I was given the opportunity to run the Australia and New Zealand operation of BMGZomba Production Music. A couple of years after that BMG was acquired by Universal and so I ran the Sydney-based office of Universal Production Music till 2012 before moving to London to take the helm of Universal Production Music UK. In September of this year I joined the new BMG as SVP and I am looking forward to an exciting future ahead.”

John Clifford of BMG Production Music UK.John Clifford (BMG PM UK): “For me there is no ‘before’! I’ve worked in the production music business for my entire career to date (25 years). In the beginning, I had no idea what production music even was, but as a young person simply wanting to get started in the music industry, I was given the opportunity of my first ‘real’ job and I started at the age of 18 working for an independent production music publisher called Nightlight Music in Sydney, Australia. Almost five years later, I joined Zomba Production Music as an Account Manager and not long after that became Head of Marketing. BMG subsequently acquired Zomba, and in mid-2005 I was given the opportunity to run the Australia and New Zealand operation of BMGZomba Production Music. A couple of years after that BMG was acquired by Universal and so I ran the Sydney-based office of Universal Production Music till 2012 before moving to London to take the helm of Universal Production Music UK. In September of this year I joined the new BMG as SVP and I am looking forward to an exciting future ahead.”

Paul Gulmans of BMG Production Music Netherlands & Germany.Paul Gulmans (BMG PM Netherlands & Germany): “I am a guitarist/composer and studied sociology and musicology. Accidentally I entered the production music business and was blown away by the fact that everyone listens to production music daily by simply watching TV, but the vast majority of the people are unaware of the existence of the production music business — as I was before I got involved. I like the fact that the production music business enables a lot of musicians, composers and other music lovers to work in the music and media industry, when they don’t aspire to pop stardom. I also like the fact that the business is very sales-driven.”

Paul Gulmans of BMG Production Music Netherlands & Germany.Paul Gulmans (BMG PM Netherlands & Germany): “I am a guitarist/composer and studied sociology and musicology. Accidentally I entered the production music business and was blown away by the fact that everyone listens to production music daily by simply watching TV, but the vast majority of the people are unaware of the existence of the production music business — as I was before I got involved. I like the fact that the production music business enables a lot of musicians, composers and other music lovers to work in the music and media industry, when they don’t aspire to pop stardom. I also like the fact that the business is very sales-driven.”

Stewart Winter (Video Helper): “I worked as an associate TV promos producer at ABC News and got sick of trying to find appropriate library music, so I met my business partner Joe Saba, who was the roommate of the woman I was dating at the time, and we decided to start writing our own music that was easier to edit and got to the point faster.”

Stewart Winter of Video Helper. Composer takeaway: Remembering that those to whom you send demos are human beings with varied backgrounds might help you get beyond seeing us as walking cash cows whose job it is to get placements for you and make you rich. Perhaps we are, but you can be nice about it!

Stewart Winter of Video Helper. Composer takeaway: Remembering that those to whom you send demos are human beings with varied backgrounds might help you get beyond seeing us as walking cash cows whose job it is to get placements for you and make you rich. Perhaps we are, but you can be nice about it!

- Channelling Angry Forum Composer, are library publishers just greedy middlemen who take money from writers without doing anything? What do you do all day in your big comfortable offices on your giant salaries while composers suffer for their music? Why do writers need publishers at all?

John Clifford (BMG PM UK): “Ha, great question… I wish I had a big comfortable office! But if I did I wouldn’t spend much time sitting in it! Publishers need to employ and manage a sales team, creatively market the catalogue of music they are responsible for and manage and maintain a delivery platform to ensure the music they are responsible for gets into all the hands that it should be. So apart from drinking five or six double espressos per day, I’m all about building the best possible team I can and creating partnerships with media heavyweights to ensure revenue success. Believe me when I tell you that I could give you a very long list of production music composers who earn a hell of a lot more than I do, which is probably testament to our success and the great job we do for them.”

Paul Gulmans (BMG PM Netherlands & Germany): “Production music tracks don’t sell themselves. Production music is not played in the Top 40 or on the radio: it needs to be sold and that’s what we do with passion. We visit, call and contact clients, advising and helping them in their search for the right track. BMG Production Music offers fairness, transparency and service to composers, publishers and clients.”

Questions From The Floor

Time now to open the floor to some curious composers...

- Andrew Skipper: What approach is most likely to result in you listening to demos and them getting placed?

Stewart Winter (Video Helper): “If the email doesn’t seem cookie-cutter and actually shows that they’ve done the research, we’re usually going to give it a much closer listen. Each track has about eight seconds to catch our attention. Take longer than that for more than three cuts and I’ve started doing something else.

“Don’t write what already exists. People want something different and interesting. Don’t just write to the lowest common denominator and think ‘This is good enough for TV music.’ Impress the shit out of the listener. Want to make something that sounds big? Make it BIG. And then bigger still. And then bigger still. Stand out. And remember: the end user will quite possibly have to edit your work. Don’t go crazy with tempo or key changes. End the piece with a root note — and, if you can, avoid the third, so it works as a dark or a positive ending.”

Paul Gulmans (BMG PM Netherlands & Germany): “Compose with a visual in mind. Human beings are very visually oriented. If a client is working on a documentary about the African Savannah and we have a CD with a beautiful picture of an African Savannah on it, they will listen to those tracks first. Remember, too, to write music where a voiceover can be added easily without interfering with loud lead instruments. Also, write positive music, as people want to feel good, write timeless music so it can be used 15 years from now, and write minimal music, as this is very easily implemented in any production.”

John Clifford (BMG PM UK): “Know your sweet spot and aim to write and produce the best material you can in your given niche. Don’t try to do everything, do what you are good at and do it well. It drives me crazy when a writer tells me they can write and produce any genre! Maybe they can, but I bet not all of it will be great! Stick to your sweet spot! A good composer understands music to picture and doesn’t try to be over-creative or too clever. We are in the business of creating and selling high-quality, well-produced functional music, and these are the tracks that make the most money. So, as a composer, find your niche, make your tracks functional and be excellent at it!”

Composer takeaway: There is lots of great advice for you to digest. Tailor your emails to the company, grab attention from start of the track, be interesting, impressive, visual, positive and minimal, and be the best in your niche rather than trying to be great at everything. They are all great tips, which I strongly agree with, although there are exceptions too. Not all music has to be positive or minimal (trailer music is usually neither), and although no-one should try to be a jack of all trades, it’s also good to try new approaches sometimes, rather than getting stuck in a rut or left behind.

- Nainita Desai: What are your plans to adapt and evolve in an already oversaturated market and stay one step ahead of the pack?

John Clifford (BMG PM UK): “I believe there is always room for new competition in the market. For a publisher, success in the production music business rests on three pillars: great people, great catalogue and great technology (delivery platform). BMG Production Music are in the process of reshaping all three.”

Paul Gulmans (BMG PM Netherlands & Germany): “Clients always want to use new music, so the market is not saturated, but getting the music a client needs fast is getting more and more important. Here’s where technology plays a leading role. That being said, our clients still need and appreciate the personal contact from our music supervisors, so the ‘organic’ factor continues to be important.”

Composer takeaway: Note that John and Paul both mention keeping up with technology and both express confidence that the market remains strong. To this I would add that we have the tail wind of a fast-growing customer base as more people create better quality promotional videos on YouTube and Facebook, needing quality music. Small new companies can prosper becoming well known in boutique niches while large companies can invest in staff who can get out and talk to clients and give fast, helpful and personal support.

- Chris Smith: How do you see production music developing over the next 10 years?

Stewart Winter (Video Helper): “Production values will increase, there will be a huge leap in competition.”

To this I would add that we can also expect technology that helps clients find exactly what they need quicker to cut through the growing competition, although we should perhaps also expect the unexpected if novel business models or as-yet unknown technologies sweep through the market.

- Martin Gratton: Where do you look for trends or gaps in the market?

Stewart Winter (Video Helper): “Our trends and directions come more from the storytelling aspect. For example, most libraries jumped on trap and dubstep when they were big, but in five years, they’ll be outdated. We look for current ways people are telling stories in promos and trailers and who’s breaking conventions, and try to come up with different ways of designing music to fit those unconventional ways.”

I agree that we also don’t exactly follow trends; it’s more that we create new music to solve problems or when we’re inspired by an idea. For example, sometimes clients ask for something that we don’t have. Sometimes a novel piece of music will lead to a whole album where the concept could be explored more deeply. Inspiration can also come from listening to clients talk about what they are trying to convey and realising that something new is needed to achieve that.

- Ron Kujawa: What is the most common mistake you see from prospective writers?

Stewart Winter (Video Helper): “That they try to sound like everything else on the radio/TV instead of showing us that they can create and deliver an interesting concept, not just a snappy earworm or pop song. Show us you’ve created something that we haven’t heard before. Too many people just create hundreds of tracks of stuff that’s already saturating the airwaves and will be outdated in a few years.”

- Jaap Visser: A lot of music publishers are, or were, composers. Do you think that benefits your business, or do you find that it makes it harder?

Stewart Winter (Video Helper): “Having been (and still being) a composer, I find it’s given us a certain competitive and advantageous perspective on the music library business. We understand how to communicate with our composers better and also understand (and translate into music) the needs of our clients. After years and years of clients telling us they want more music that’s ‘more blue and smells like saffron’, we finally can translate that into directions and concepts.”

Amen to that! As a composer, I can be very concrete about what will fix certain mix problems, and know when to tell someone to add a filter to the reverb, or lengthen the attack time on the snare compressor. I remember some of my non-composer publishers driving me nuts with their vague change requests.

- Rob Green: Do you feel we need to submit more experimental tracks and push the boundaries, or is this not viable?

Stewart Winter (Video Helper): “If you don’t submit something that makes you sound different, you get lost in a sea of mediocrity. Sure, prove you can do the standard stuff, but feature the things that stand out and make people ask ‘What the hell was that?’ — in a good way, I hope. Picasso had to learn to paint photorealistic stuff before he started putting people’s noses on their foreheads, and production music works the same way: to make stuff that stands out, you have to understand how to make the basics.”

My own view is that it depends how great your production is, and how emotional and evocative the music is. If it has a fantastic production, is highly emotional and evocative and it’s also experimental and original, that’s amazing, so yes please! Experimental but weakly produced, unexpressive music won’t get you too far.

Composing Vs Publishing

Some important questions duly answered, as a final thought I’d like to add my comparison of the experience of being a composer and publisher. After seven years spent solely as a library music composer, followed by another seven as a library publisher, I will say that writing music for a living was a fantastic privilege which I didn’t intend to give up. I started out thinking of publishing as a sideline, but out of a desire to do it well, allowed it take over my workload until I now have no time left to write music.

Being a composer certainly has its problems: having to find publishers who will take your music, the insecurity of waiting for income, the isolation of working alone, dealing with lack of inspiration and struggling with procrastination, but publishing also has its thankless moments. There are endless contracts to collect, information portals to learn and navigate, clients to please, spreadsheets to create, problems to fix and bullets to dodge while trying to keep everyone happy. As for which pays better, experienced library composers with over 10 years of productive, high-quality music creation behind them earn much more than the vast majority of publishing employees.

There are certainly rewarding aspects to publishing like developing great projects, teams, plans, networks, brands, people and travels. However, I’ve been a composer and I’ve been a publisher, and overall I found it a bit more enjoyable being a composer, thanks to the artistic challenges and nerdy tech fun of playing with gadgets and software all day.

In Conclusion

Hopefully, this snapshot of the library publisher’s world has given you a better appreciation of their complex work, which should help your communication with the people who promote your music to their clients and generate royalties for you. At the very least, maybe next time you read an anti-publisher rant you might remember that in fact most of us competitive, overworked, walking cash cows are actually pretty OK.

Let Me Count The Ways...

For a very helpful further answer to the question ‘What do music publishers actually do?’, check out the rather wonderful infographic [shown right, click for larger view] specially prepared just for our question by the PMA (the US-based Production Music Association www.pmamusic.com), which provides a robust summary of all the tasks that library publishers take on in order to produce these albums and create an income for you. As you can see, publishers have composers to find, album ideas to dream up and choose, music in progress to feed back on, clients to find, learn from and sell to, contracts to create with writers, performers and distributors, masses of data to compile and upload, and a mountain of accounting: company accounts, international distributor royalty calculations and composer royalty calculations.

For a very helpful further answer to the question ‘What do music publishers actually do?’, check out the rather wonderful infographic [shown right, click for larger view] specially prepared just for our question by the PMA (the US-based Production Music Association www.pmamusic.com), which provides a robust summary of all the tasks that library publishers take on in order to produce these albums and create an income for you. As you can see, publishers have composers to find, album ideas to dream up and choose, music in progress to feed back on, clients to find, learn from and sell to, contracts to create with writers, performers and distributors, masses of data to compile and upload, and a mountain of accounting: company accounts, international distributor royalty calculations and composer royalty calculations.

That’s just when things are going well. There are also endless challenges like chasing money from non-payers, fixing errors, cash flow to manage, agents not doing their jobs who need nagging, copyright infringement claims, composers not handing in scores in time for orchestral recordings and people not answering urgent emails. There can also be fraught relationships to manage if co-workers, clients, agents, writers or designers get into disputes. Any two people can escalate grudges and blunt honesty into an argument and that stress can come from any direction.

So, hopefully, the next time you hear annoyed composers telling you that publishers are idle middlemen who take their earnings without doing anything, take a good look at this infographic, and think about whether you’d rather write music all day on a much higher eventual income than any individual publishing employee, or carry out these endless office and sales tasks while trying to solve a constant supply of stressful problems.

All About Library Music: Part 1 Getting Started

All About Library Music: Part 2 The Business

All About Library Music: Part 3 The Composer

All About Library Music: Part 4 The Client

All About Library Music: Part 5 Networking

All About Library Music: Part 6 Hollywood Trailers

All About Library Music: Part 7 How To Write Trailer Music