Photo: HiFi Vintage / Christian Grados, Paris

Photo: HiFi Vintage / Christian Grados, Paris

One of the best-selling albums of all time was mixed on a long-forgotten experimental hi-fi speaker. Forty years later, are Philips' innovations finally catching on?

Back in the 1970s, the vast Dutch electronics manufacturing company Philips had a higher profile around the home than they do now. As they do today, Philips manufactured everything from vacuum cleaners to lightbulbs via televisions and consumer hi-fi, but back then I think it's fair to say that the company were rather more adventurous and idiosyncratic with product design, quite often with a uniquely European take on aesthetics. They also weren't afraid of being radical in terms of technology, and a perfect example of that was their RH series of "motional feedback" hi-fi speakers. The RH series were so far ahead of the technological curve that, as far as I'm aware, no major consumer audio manufacturer has even flirted with the same idea since.

But before I explain why the RH series was unusual, and what its story is doing in a pro audio magazine, a bit of context is probably worthwhile. Active speakers have long been popular in studio and PA applications, but traditional hi-fi circles have been slow to adopt the principle. We're just starting to see active speakers make inroads into consumer hi-fi. Of course, smart speaker products like the Google Home, Amazon Echo and Apple HomePod are effectively active, as are the all-in-one streaming audio solutions such as the Bowers & Wilkins Zeppelin and Dynaudio Music, but it's ony recently that more conventional active speakers have begun to find acceptance in this sphere. Good examples are the KEF LS50 Wireless and the Kii Three, a speaker that's making as big an impression among consumer audiophiles as it is among those who are studio-based. But if you're looking for the first serious range of active speakers aimed at the consumer audio market, then you're looking for the Philips RH series, introduced in 1974.

However, it wasn't only in being active that the RH series was innovative. Along with line-level inputs, electronic crossover filters and separate amps for each driver, it had another significant trick up its 1970s sleeve: motional feedback.

Motion Capture

Motional feedback refers to the incorporation of an idea that speaker engineers sometimes discuss in after-hours, knockabout, 'what if' brainstorms, but which is only rarely implemented in practice: low–frequency error correction. The problem that such error correction strives to solve is that the control an amplifier exerts over the movement of a driver diaphragm at low frequencies, say, below 200Hz, is relatively imprecise. The diaphragm has inertia, so is both hard to get moving and hard to stop. And the diaphragm suspension has both hysteresis, meaning it never quite returns to its original resting position, and non-linearity, meaning it doesn't exactly follow the input signal. As a result, a bass driver diaphragm is hardly ever located exactly where the amplifier, and input signal, says it ought to be, or indeed moving at the intended velocity, and the result is distortion. Much of the characteristic increase in speaker distortion at low frequencies is a result of this lack of amplifier control.

Andy Jackson: "We used them quite a bit in mixing sessions, the way that maybe now you'd use NS10s: get some sounds up on the big monitors then go to the little ones for balance and stay there.

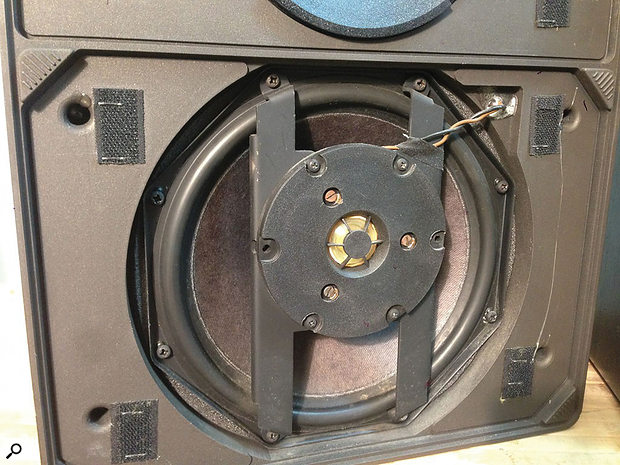

Philips' "motional feedback" technique for error correction involved the attachment of a small and lightweight piezo-electric accelerometer to the underside of the bass driver dust-cap. The output of the accelerometer was returned to the amplifier and compared to the input, and the resulting error-correction signal used to modulate the amplifier output. As with any feedback error correction system, some latency is inevitable, but there's no doubt the technique can significantly reduce low-frequency distortion, while at the same time enabling optimisation of a speaker's diaphragm–movement–limited power handing (as a by-product, it will also fix the effects of thermal compression as the voice coil temperature and electrical resistance rises). The RH series, by many contemporary accounts, worked as intended. They had really great bass, especially considering their compact dimensions.

The RH544 incorporated an accelerometer that delivered 'motional feedback' to the built-in amp.

The RH544 incorporated an accelerometer that delivered 'motional feedback' to the built-in amp.

But, I suspect you're now asking, what has Philips' curious motional feedback active hi-fi speaker range got to do with professional audio and music recording? Well, what if I told you that a number of classic Pink Floyd albums, including The Wall, were mixed on a pair of Philips RH544s? Andy Jackson, David Gilmour's long-time engineering collaborator, takes over the story:

"I didn't work on The Wall project but we were still using the 544s after that on The Final Cut, The Division Bell and on Roger [Waters]'s Pros & Cons Of Hitchhiking album. I owned a pair for a while. What they seemed to provide was bottom–end extension, much more than anything else of that size. It was also actually really hard to get a mix to sound good on them, so you really had to work at it. We used them quite a bit in mixing sessions, the way that maybe now you'd use NS10s: get some sounds up on the big monitors then go to the little ones for balance and stay there. They fell by the wayside in the end and my pair got sold on to a friend."

A Period Of Inactivity

Much like Andy's pair of RH544s, Philip's experiment with motional feedback and active speakers fell by the wayside. By the mid-1980s, motional feedback had disappeared from the Philips brochure. But the idea of feedback and error correction wasn't completely forgotten. At least two current pro monitor manufacturers — Kii Audio with the Kii Three (that speaker again), and Swiss monitor company PSI — employ a related technique where an error-correction signal is generated electronically by sensing the current in the driver voice coil and comparing it with the input signal.

If you fancy trying the original idea by finding a pair of Philips RH544s like Andy's, probably your only option is eBay. And then, when you have a pair, you'll likely need somebody who knows their way around speaker drivers, electronics and soldering irons to restore them. But, at the end of the day, you'll be able to tell people that The Wall wouldn't sound the way it does without a weird pair of speakers like yours.

Thanks to Andy Jackson (www.tubemastering.com) for his help with this piece and Mark Thompson at Funky Junk (www.proaudioeurope.com) for inadvertently inspiring it.