Arturia’s MatrixBrute combines everything the company know about synthesis into one hugely ambitious machine.

Two years ago, Arturia’s designers found themselves in a bit of a pickle. The MiniBrute had proved to be a great success, while the more recent MicroBrute looked as if it too would be a winner. So, what to do next? Perhaps it’s not surprising that someone suggested that the company develop a MiniBrute with memories. Likewise, it’s not surprising that somebody else suggested a semi-modular MiniBrute that could be patched like an MS20 or an ARP 2600. So the idea of a MiniBrute that had memories and could be patched was born. Arturia then ran into a problem that has existed for more than 50 years: how can patch cables remember which wotsit was connected to what thingy, and by how much one affected the other? Short of a Disney-esque cartoon in which your patch cables walk across the studio and jump into the right sockets, the concepts of patching and memories are not complementary, and it’s an almost intractable problem.

But more than 30 years ago, an almost unknown English company found a solution. Datanomics, which had purchased the embers of EMS in 1979, wanted to release an instrument based on the Synthi, but which dispensed with the pin matrix and connected the wotsits to the thingies using an array of switches whose states could be remembered by a microprocessor. Thus was the DataSynth born. Or, to be more precise, thus was the DataSynth almost born. The prototype was unreliable and the synth never made it into production, which is just as well because the projected price in 1984 was around £3500, which would have made it unaffordable. Shortly thereafter, Datanomics sold their rights in the EMS synths and vocoders, and no more was heard of the DataSynth. Perhaps inevitably, Arturia’s people arrived at the same solution. But when (under strict conditions of confidentiality) I was shown a mock-up in October 2014 and I asked how much they had learned from the difficulties encountered by Datanomics, I received only blank stares. Nonetheless, 32 years after the idea was mooted, the world has its first programmable, matrix-based analogue synth from a mainstream manufacturer.

Getting To Know You

Physically, the MatrixBrute is an imposing bit of kit, thanks in part to its generous four-octave keyboard, and in part to its resplendent control panel, which bristles with knobs, faders and buttons. In fact, the MatrixBrute looks and feels like nothing so much as a small Waldorf Wave, which is not surprising since they share the same designer.

Although the review unit was a pre-production model, I was impressed by its build quality and the attention to detail. For example, the flip-up support that holds the control panel in position when raised is over a foot wide, ensuring that there’s no wobble when you lean on one side of the panel or the other. There’s also a latch that locks the panel in place when it’s flat, which is very welcome when carrying the synth around and shipping it. I was also impressed by how firm and smooth the knobs felt, and then there were things like the Arturia logo milled into the inside of the pitch-bend and modulation wheels, which illustrates love rather than necessity. Finally, there’s the Arturia logo just behind the keyboard. It’s not a badge. Each letter has been cut out individually and recessed into the wood. Even before switching on the MatrixBrute, I had started to like it.

Although Arturia describe it as an “Analog Matrix Synthesizer”, the MatrixBrute is an analogue/digital hybrid, meaning that its signal path is analogue, but the things that affect this are digital. In the past, synths with hybrid architectures suffered from an effect known as zipper noise when coarsely quantised parameters were swept quickly across their ranges. Fortunately, this is now behind us. The MatrixBrute’s 12-bit encoders offer more than 4000 values lying between a knob’s clockwise and anti-clockwise extremes, and its 14-bit control signals translate to CVs with more than 16,000 values lying between, say, 0V and 5V. This ensures that everything sounds smooth and analogue, which is just as well because there are at least two important reasons why the use of hybrid architecture is a very good decision for a synth with a matrix.

Firstly, imagine that you’re creating a sound on a vintage synth such as an EMS VCS3 or a Maplin 5600S. If you take a single source and direct it to multiple destinations it suffers what’s called voltage droop and, as you add pins, you have to adjust the knobs to keep everything doing what you had intended. Because the MatrixBrute’s modulation signals are calculated digitally, there’s no droop. The second benefit is perhaps even more valuable. Above the matrix you’ll find a knob called Mod Amount and, when you select a route, you can determine the amount by which the source will affect the destination, with either positive or negative effect. So, unlike a vintage synth on which a given source affects each destination equally, the MatrixBrute has the equivalent of 256 programmable amplifiers underneath the matrix — one for every possible source/destination combination. On a modular synth this would require a wall-sized array of 16-channel CV Buffers and 16-channel CV Mixers, and I’m not even sure that these exist. But lest you think that the MatrixBrute’s matrix is superior in every way to those of its spiritual forebears, it isn’t. This is because it doesn’t provide access to the audio path itself, so you can’t use the oscillators as modulation sources within it or do things such as placing the effects before the filters, all of which are possible on a VCS3. Philosophically, therefore, the MatrixBrute is equivalent to the Korg MS20, which means that some of the wilder and more experimental aspects of synthesis are beyond its reach.

Although the matrix has 16 rows it offers 18 inputs because rows 15 and 16 accept signals from two sources. And, although it has 16 columns, there are only 12 pre-defined outputs. (See table.) But the four undefined outputs prove to be one of the synth’s most powerful features. If you count up the number of knobs and sliders to the left of the matrix itself, you’ll find that there are more than 60 of these, all of which can, in principle, be modulation destinations, as can the effects parameters, the fine tune, the portamento speed and the Macro knobs (which are themselves sources in the matrix). However, an 18 x 75 matrix would be impractical as well as expensive, so columns 13 to 16 are assignable; while in Mod mode, you just hold down the appropriate button and then twist the knob or slide the fader that you wish to assign to it. The small LED screen will then flash to show you that you’ve made an assignment, the chosen output will be displayed within it, and you can direct any of the modulation sources to it. Sure, it’s not the same as having a matrix the size of a table tennis table, but it’s a good compromise between cost, size and flexibility. Just be aware that none of the MatrixBrute’s switches can be assigned as destinations so, for example, you’re not going to be able to use the matrix to jump from one oscillator waveform to another or to switch the output assignments in the audio mixer.

An Analogue Signal Path...

Arturia have retained the MiniBrute architecture for the first two oscillators in the MatrixBrute, so each offers simultaneous ramp, pulse and triangle waveforms, and each of these has a dedicated waveshaper. For the ramp wave, this is called Ultrasaw, and it adds two phase-shifted copies of the wave to the original. A dedicated LFO provides a gentle, chorused sweep to the second wave, while you can apply the full force of the modulation matrix to the third. The waveshaping for the pulse wave is PWM and, again, you control this from the matrix. Then there’s the triangle wave shaper, called the Metalizer, and the range of sounds that you can obtain from this is immense, from interesting new static waveforms to modulated effects that make hard sync sound pedestrian. Both of these oscillators offer coarse tuning of ±24 semitones and fine tuning of ±1 semitone, and each incorporates a sub-oscillator although, unlike the MiniBrute’s (which offers -1 and -2 octave options), the MatrixBrute’s are fixed at a single octave down.

The third oscillator offers four waveforms — sawtooth, square, triangle and sine — again with coarse tuning of up to ±24 semitones. It has no waveshaping options, but instead offers you the option to switch off keyboard tracking. This can be very useful when it’s used as an audio frequency modulator or as an LFO (both of which we’ll come to in a moment). Next to this lies the noise generator, which offers blue, white, pink and red noise options.

So, what’s all this about audio frequency modulation? If you turn to the Audio Mod panel, you’ll find seven modulation routes: VCO2 being modulated by VCO1, either VCO1 or VCO2 being modulated by VCO3, either the VCF1 cutoff frequency or the VCF2 cutoff frequency being modulated by VCO3, and either VCO1 or the VCF1 cutoff frequency being modulated by the noise generator. As you can imagine, the opportunities for torturing the MatrixBrute’s defenceless little transistors are legion, and the poor things will scream and wail in gut-wrenching fashion if you force them to do so, although you can also wring a wide range of euphonic sounds from Audio Mod. Commendably, these patches exhibit a consistent tone across the keyboard, which is almost never the case with analogue synths because such sounds are incredibly sensitive to tiny tuning inaccuracies. You can also sync VCO1 to VCO2 for all the usual effects, and you can use the FM and sync options simultaneously. Strangely, there’s no ring modulation or audio-frequency amplitude modulation on offer, which is a shame.

When Arturia announced the MiniBrute, I was surprised that the company had chosen a 12dB/oct Steiner Parker filter for it. That concern was echoed by many others, with two schools of thought eventually emerging; one (including me) that embraced the MiniBrute because it had a different character when compared with other synths, and the other that decried it for exactly the same reason. I was therefore delighted to find that the MatrixBrute includes both Steiner Parker and Moog-style multi-mode filters, each with 12dB/oct and 24dB/oct modes, and each with independent drive levels and Brute Factor feedback loops that can make them scream and complain in all manner of ways.

So, returning to the signal path, we find that the MatrixBrute’s audio Mixer offers five inputs (VCOs 1, 2 and 3, noise, and any signal presented to the external signal input) each with two outputs: one to VCF1 (the Steiner Parker filter) and one to VCF2 (the Moog-style filter). You can direct the signal from each source to either or both filters, and you can even determine whether the filters are configured in parallel or in series, the latter with VCF1 preceding VCF2. Furthermore, each filter offers low-pass, high-pass and band-pass options, and VCF1 adds a further notch (band-reject) mode. This makes it possible to craft a huge range of filter responses, including some intriguing formant-style profiles.

The MatrixBrute is a substantial bit of kit, weighing in at 20kg and its front panel measuring 860 x 432mm.

The MatrixBrute is a substantial bit of kit, weighing in at 20kg and its front panel measuring 860 x 432mm.

Both filters self-oscillate at high resonance, and it was while testing this that I discovered some fascinating differences between them. Things were much as expected when I tested the ladder filter. This oscillates with a frequency range of 20Hz to 20kHz in all three modes, and tracking is pretty accurate, which means that many of my favourite analogue patches are available. The pitch of the self-oscillation is the same in both 12dB/oct and 24dB/oct modes although, strangely, the high-pass mode’s oscillation is about a semitone higher than that of the others at the same settings. But in a novel twist, Arturia have ensured that this filter can pass low frequencies unimpeded at high resonance settings (which is a good thing) and that it self-oscillates down to its lowest cutoff frequency. So while VCF1 may be Moog-y, it’s not Minimoog-y, which, as I later discovered, was to allow me to create some excellent sounds that wouldn’t otherwise have been possible.

Turning to the Steiner Parker filter, things were rather different. This oscillates from around 200Hz to 16kHz in its LP, HP and BR modes, but not at all in its BP mode and, while the oscillation frequencies are fairly consistent when you switch between modes, they’re not identical. Furthermore, the tracking is less accurate, and the oscillation frequency jumps about a semitone when you select the 24dB/oct mode. What’s more, its cutoff frequency exhibits a short slide up to the selected pitch each time that you trigger a note. However, in contrast with the ladder filter, the diminishing resonance at low frequencies means that you can create sounds that are resonant in the mid and upper frequencies but less so in the bass, which is very much a Minimoog attribute. Weird!

Between the two filter panels, you can’t help but notice a large knob labelled Master Cutoff. This is an encoder that affects the cutoff frequencies of both filters equally, shifting whatever frequencies have been determined elsewhere. I fear that many users will use this as a performance control, frantically twisting it from one side to the other as if their lives depended upon it. But, since you can assign it as a destination in the matrix, there are many more elegant uses for it.

At the end of the audio signal path, you’ll find an effects panel that offers five options — single-channel and ping-pong delays, chorus, flanger and reverb — all generated by a single set of BBD chips. You can only select and use one effect at a time but, if I’m honest, it’s unlikely that I would use these for anything other than special effects. This is because of two less than ideal attributes. Firstly, the waveform modulating the delay line is akin to a square wave, which leads to some odd results at certain settings. Secondly, the filter that stops the BBD clock from intruding into the audio has a very low cutoff frequency, so much so that higher notes can’t be delayed! But despite these limitations, I’m sure that you’ll come up with some weird and wonderful results, especially if you map the effects’ parameters to columns 13-16 in the matrix. But don’t throw away your digital multi-effects units just yet.

The final controls in the signal path comprise the global fine-tuning control (±1 semitone), the master volume control, and the headphones level control, which is not affected by the master volume.

...Controlled By Lots Of Digital Bits

The MatrixBrute offers two programmable LFOs with seven waveforms, three triggering modes (free running, single cycle and multi-triggering), and sequencer sync. What’s more, LFO1 offers variable phase, while LFO2 has variable delay followed by a fade-in so that you can use it as, say, a delayed vibrato. If there’s one area in which they seem lacking, it’s their maximum frequency, which is quoted as 100Hz, but which I measured to be closer to 80Hz. So this is where the LFO output from VCO3 comes into its own. You can select this to be at a frequency of 1/16th, 1/32nd, 1/64th or 1/128th of the audio frequency generated, which means that it ranges from about 0.06Hz to as high as 400Hz, although with a huge amount of quantisation of the range at the upper end of the scale.

It also sports one HADSR contour generator (which offers a delay of between 2ms and 10s before the attack begins) and two ADSR contour generators. None of these offers the slow/fast speed modes of the MiniBrute’s filter contour, but their responses range from around 1ms (the fastest obtainable on the MiniBrute’s fast range), to around 10s (the slowest on the MiniBrute’s slow range). The first of the ADSRs is hardwired to the filters’ cutoff frequencies, while the second is hard-wired to the audio signal VCA, and both have faders that make their amounts velocity sensitive. In contrast, the HADSR has to be patched in the matrix before it can affect anything.

To the right of the matrix, you’ll find the MatrixBrute’s sequencer, which uses the matrix buttons to represent its arpeggios and sequences visually in ways that you would expect more from dedicated software or plug-ins.

Its first mode is a simple arpeggiator offering up, down, up/down and random modes, with a root range of one to four octaves. You can use the internal clock to determine the rate (30 to 260 bpm) with clock divisions of 1/4th, 1/8th, 1/16th and 1/32nd, plus common time, triplet and dotted-note options. There’s also a tap-tempo button. If external sync is selected, the internal clock is ignored and the controls will affect how the arpeggiator responds to the incoming clock. You can also determine the Gate length and set the amount of swing from 50 (none) to 75 percent.

Next, the Matrix Arpeggiator mode allows you to create mini-sequences of up to 16 steps from four played notes, using the top four rows of the matrix to determine whether a note is played on a given step, whether it’s tied, whether it’s accented (an increased velocity is sent to the contours’ Velo/VCF and Velo/VCA sliders), whether glide is applied, and whether a modulation CV (which is sent to the ‘Seq Mod’ row of the matrix in programming mode) is generated. The bottom 12 rows then allow you to determine which note is played in which octave on each step. You can also shift any given note up or down by a semitone, which means that all 12 notes in the octave are available. I don’t recall seeing anything like this before, and I’m sure that people are going to find good uses for it.

The dedicated, 64-step sequencer mode is similar. You can set the sequence length and record in real time (although this is, of course, quantised to the steps), in step time, or by accessing steps individually and replacing existing notes. The timing options as well as the Gate and Swing parameters are the same as those for the arpeggiator modes and, like the matrix arpeggiator, each step can have six attributes: the note, trigger, tie, accent, slide and modulation. In this mode, the programmed pitches are played when you press middle ‘C’, and you can transpose them up and down by playing the keyboard in the usual fashion. You can also edit sequences in real-time while playing. Perhaps best of all (and in common with the arpeggiator) the output from the sequencer can be sent to the outside world via MIDI, either to play other instruments or to be recorded in a workstation.

The MIDI Control Centre

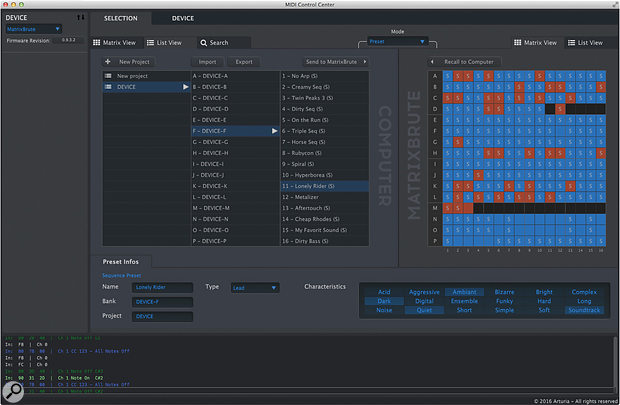

When I received the review unit it hosted an early development version of its firmware, so my first task was to hook it up to my MacBook Pro via USB and use Arturia’s free MIDI Control Centre software to update it to the latest (also pre-release) version.

Arturia MatrixBrute MIDI Control Centre.

Arturia MatrixBrute MIDI Control Centre.

Having done so, I used the software to set up the MatrixBrute’s MIDI parameters (all of which are, I think, self-evident from their names) as well as a handful of detailed parameters: pedal responses, the knob mode, the velocity curve and whether the sequencer and arpeggiator send notes via MIDI.

The second use of the MIDI Control Centre is as a patch and sequence librarian. Empty locations are shown in black, while those in blue hold a memorised sound, those in blue with an ‘S’ have a sequence saved with the sound, and those in red with an ‘S’ have a sequence that will automatically start playing as soon as the sound is selected.

You can pick up and move stored sounds and sequences just by clicking and dragging and, of course, save and recall individual sounds or complete libraries to and from your computer’s storage.

Performance & Connectivity

It’s nice to see so many performance facilities provided. Most obvious are the pitch-bend and modulation wheels, the former of which has a range of up to ±12 semitones, and the latter of which can be directed to the matrix, or to the master filter cutoff frequency, or to the depth of a direct modulation path from LFO1 to the oscillators’ pitches (vibrato), or to the amount of LFO1 when it’s acting as a modulation source in the matrix. Above the wheels you’ll also find the octave switches (0, ±1 octave, ±2 octaves) that affect the CVs and MIDI Note numbers generated by the keyboard and, alongside these, the Glide panel offers on/off and glide time (0s to 2s) while the Play Controls determine the triggering mode (single or multi triggering, with glide on all notes or just on legato notes) and the note priority (low, high and last). Lastly, there’s a Hold button.

The other four knobs on the performance panel are labelled Macro knobs, M1 to M4. These act as inputs to the matrix and they provide a convenient way for you to control multiple destinations using a single control. M3 and M4 are summed with expression pedal 1 and expression pedal 2 respectively, which suggests some interesting possibilities, and I was fascinated to find that these knobs can also be allocated to be modulation destinations, which suggests yet more possibilities.

The MatrixBrute also offers three voicing modes. The first of these is obvious enough; Monophonic makes it operate as a conventional monosynth. The second is also pretty obvious; Paraphonic allows you to play it as a three-voice paraphonic synth with one oscillator per note. Given the limitations of VCO3, this isn’t as much of a bonus as you might hope, but you can still sculpt some interesting patches this way. The third, Duo-Split, is not obvious. This creates two sounds either side of a user-definable split point. Firstly, any of the sources in the mixer can be directed through VCF1 and the usual VCA and controlled by Env 1 and Env 2 respectively, and the sound generated by this is playable above the split point. Secondly, any of the sources may also be routed through VCF2 and an otherwise hidden VCA, both of which are controlled by Env 3, and the sound generated by this is playable below the split point. In this mode, the sequencer and arpeggiator are also routed to the lower part, so you can control a sequenced sound with your left hand while soloing with your right. Some of the online demos use this to show off the MatrixBrute to good effect, and it’s something that you’re going to want to try.

So far, I’ve barely mentioned the MatrixBrute’s considerable abilities to talk to the outside world, but this is one of its greatest strengths. If you look behind the control panel you’ll find 12 CV outputs and 12 CV inputs that match the 12 assigned columns within the modulation matrix. This means that you can send any modulation signal that you generate in the matrix to the outside world, and add any modulation signal generated in the outside world to anything that you create in the matrix. For part of this review, I placed the MatrixBrute in front of a large Eurorack system and the possibilities were almost endless. But that’s not the end of the story because almost all of the MatrixBrute’s knobs and performance controls send and respond to MIDI CCs, so you can record and automate them using suitable software. This means that (for example) you can use MIDI CCs to automate the Macro knobs to control CVs sent to external synths, while using those external synths to create audio and modulation signals that can be used within the matrix or processed using the MatrixBrute’s filters, amps and effects, or both at the same time, while running the sequencer and using its output internally while sending it via MIDI to other synths while you... Oh heck, you get the picture.

See the ‘The Rear Panel’ box for a full explanation of the MatrixBrute’s well-populated rear panel.

See the ‘The Rear Panel’ box for a full explanation of the MatrixBrute’s well-populated rear panel.

In Use

The first thing you have to do when learning to use the MatrixBrute is to check which mode you’re in — Preset, Seq or Mod — because these affect the actions of the matrix buttons: selecting patches in the first mode, programming and selecting arpeggios and sequences in the second, and acting as a modulation matrix in the third. Get this wrong, and you’ll swear profusely as you destroy something that you’ve spent the last 30 minutes developing. You should also become acquainted with the Panel button, which sets the sound to the physical positions of the knobs and sliders or, when pressed together with the Preset button, creates an Init patch as a starting point for programming. This is much more important than it might sound because, since the MatrixBrute is a hybrid with memories, the positions of its knobs and sliders may have no bearing on the sound that you’re hearing.

I started by selecting the Init patch (which has no connections in the matrix) and programmed the MatrixBrute like a conventional, integrated analogue monosynth with no patch points. At this point, I would like to say that I quickly obtained my usual range of orchestral sounds and effects from it, and soon had rich, involving synth sounds flooded out of it, but that wouldn’t be quite true. Sure, I was able to program good sounds almost immediately, but it wasn’t until I had spent a week or so using it that I obtained excellent sounds. After a fortnight, they were superb sounds! The MatrixBrute rewards time spent with it, and I eventually obtained sounds that I was genuinely proud of. (Great sentiment, lousy grammar.) These included some classic 24dB/oct ‘vintage American’ leads (some remarkably similar to those of a large modular synth that I know) as well as some stunningly Moog-y basses. Then, just the press of a button or two offered the liquid 12dB/oct tones of many vintage Japanese and European synths, while contemporary, brighter and more aggressive patches were little more than a twiddle away. Were the MatrixBrute to lose its matrix and be reduced to merely a Brute, it would still be a powerful synthesizer.

Now it was time to invoke the matrix. I experimented with its 12 predefined outputs, and spent hours (well, to be honest, days) discovering interesting sounds. But it was when I started to think about defining destinations for columns 13-16 that I got really excited. One of the simpler tricks available here involves using one contour generator to control the sustain level of another, which allows you to craft contours with more than four stages. I also became engrossed with using the performance controls (including velocity and aftertouch) to affect things such as effects depths and modulation speeds. Next, I created some complex modulation signals that weren’t routed to the sound I was playing on the MatrixBrute itself, but rather directed to the CV outputs and then on to other synths. Had this flexibility been on offer when I was a teenager, no piggy-bank in the land would have been safe.

At this point, it’s also worth mentioning the percussion sounds that I obtained from the MatrixBrute. Reaching way beyond the shaped noise of many analogue synths, I used combinations of FM, noise and feedback loops to create a huge range of such sounds, from delicate cymbals to bells, to thunderous kicks and toms, some of which were real speaker-busters. I would have loved to have sampled these and arranged them into analogue kits, but I had a deadline to meet. Someone else is going to do it, and it’s going to sound great.

Finally, I have to mention the MatrixBrute’s four-octave, velocity- and pressure-sensitive keyboard. Back in 2012, I noted that the MiniBrute’s 25-note keyboard was too narrow for conventional playing and suggested that Arturia should consider a 37-key version (the MidiBrute?) or better still a 49-key version (the MaxiBrute?). It would therefore be rude of me to fail to mention that the keyboard in the MatrixBrute is very welcome. It’s also polyphonic over MIDI, so you can use the MatrixBrute as a MIDI controller as well as an excellent hub for a modular synth setup.

Of course, nothing is perfect and, early on, I discovered that the MatrixBrute suffers from audible bleed from the oscillators through VCF1, even when all of the Mixer levels are at zero and all of the routes to the filters are defeated. I raised this with the engineers at Arturia who told me, “We had made the decision to pack the MatrixBrute with lots of features, which meant a lot of circuitry. So, when it came to the board layout it was difficult to avoid crossing the filter area with pitched signals such as the VCOs. To give you an idea of the complexity of the problem, this board has around 6000 components so, while it wasn’t something we wanted, choosing to implement a 24dB/oct Steiner Parker filter — which is sensitive to bleeding from nearby PCB tracks — led to this issue. But if you push the VCOs to very high frequencies you can eliminate it.” I tried this, and it worked. So did turning the output from VCF1 to zero when it wasn’t needed!

The next thing that concerned me was a slight ‘blip’ when triggering new notes, particularly with multi-triggering switched on. I queried this too, and the chaps confirmed that I had discovered a bug. The intended response was that the contour entered a brief release stage and then a new attack phase each time that a trigger was received, but the trigger pulse was being summed with the contour, and it was this that was generating the blip. By the time that you read this, it should have been fixed. I also found that if I changed sounds while playing, I could obtain anything ranging from a smooth transition, to a soft click, to a brief burst of audio garbage generated while the matrix connections and values were being recalculated by the firmware. This time, the engineers were already aware of this and, again, it should be fixed by the time that you read this.

No doubt there are other quirks to be discovered but, given that I’ve been playing a pre-release unit and that the firmware is still being finalised, I think that this is a commendable result — one problem with a simple workaround, and two bugs that will be fixed by the time that the product hits the streets. On a device of this complexity, that’s impressive.

Conclusions

It’s hard to pigeonhole the MatrixBrute. Is it a traditional performance synth, a source of modern EDM sounds and sequences, or a tool for advanced sound design? Is it a stand-alone instrument, something to place at the centre of a modular synth setup, or a MIDI controller that can add analogue spice in an otherwise digital studio? In truth, it’s all of these things and more, and I think that it will take some time to discover all of the possible ways in which it can be used.

So, should we be excited by it? I think that we should. If you want simplicity and instant gratification, it may not be the synth for you, but I’m still thinking of new ways to create complex modulation signals that I can send to my modular synths while playing the MatrixBrute itself, and I haven’t finished experimenting with sending the output of its sequencer to other analogue and digital synths and then processing the results using its filters and effects. Meanwhile, I’m still discovering the pleasures of synchronising its arpeggiator to external clocks while playing its powerful vintage patches in a mix of multiple instruments. At the same time... Oh, sod it. I want more time with this beast. Lots more time.

Check out the SOS Tutorial video course on Arturia MatrixBrute.

Alternatives

It’s hard to think of an alternative to the MatrixBrute. The MS20 is a close relative, but I don’t view this as a direct competitor. Neither do I class the EMS VCS3/Synthi or even the Maplin 5600S as competitors, not least because you can’t buy them except as second-hand instruments that cost insane amounts of money. Perhaps the current synth that’s closest in function is DSI’s superb Pro 2, but I would prefer to suggest a strange contender for an alternative — the Minimoog Model D, not because it’s similar, but because it’s so different. The MatrixBrute offers huge flexibility, both in terms of programming and sound, whereas the Minimoog offers little by comparison, but what it does, it does fabulously well. They’re both distinctive instruments, and they’re both designed for serious players as well as enthusiasts — opposite sides of the same coin, if you like.

The Rear Panel

The MatrixBrute’s rear panel is more complex than most because all of its 3.5mm CV patch points have migrated here rather than being exposed on the control panel. There are 24 of these (see table) together with Gate In and Out, Sync In and Out, and an audio input with a Gate Extractor. Alongside these, there are three pedal inputs (expression 1, expression 2 and sustain), plus MIDI on USB as well as five-pin DIN sockets. Further audio I/O is handled by a TRS insert point that sits before the internal effects and, finally, there are stereo audio outputs. (The stereo headphones output is at the front of the instrument.) The rear panel is completed by a memory protect switch and an IEC socket for the synth’s universal (100V-240V, 50/60Hz) power supply.

|

MatrixBrute Analogue Connectivity |

|||

|

VCO1 pitch |

CV In |

CV Out |

0 -10 V |

|

VCO1 ultrasaw amount |

CV In |

CV Out |

±5V |

|

VCO1 pulse width |

CV In |

CV Out |

±5V |

|

VCO1 Metalizer amount |

CV In |

CV Out |

±5V |

|

VCO2 pitch |

CV In |

CV Out |

0-10 V |

|

VCO2 ultrasaw amount |

CV In |

CV Out |

±5V |

|

VCO2 pulse width |

CV In |

CV Out |

±5V |

|

VCO3 metalizer amount |

CV In |

CV Out |

±5V |

|

Steiner filter cutoff frequency |

CV In |

CV Out |

0-10 V |

|

Ladder filter cutoff frequency |

CV In |

CV Out |

0-10 V |

|

LFO1 amount |

CV In |

CV Out |

0-10 V |

|

VCA gain |

CV In |

CV Out |

0-10 V |

|

Gate |

In |

Out |

0-5 V |

|

Sync |

In |

Out |

0-5 V, Clock, Gate, 24ppqn, 48ppqn |

|

Expression |

2 x In |

--- |

3.3V |

|

Sustain |

In |

--- |

--- |

|

Audio In with envelope follower and gate extractor |

In |

--- |

Instrument and line levels |

The Modulation Matrix

|

Row |

Input |

Column |

Output |

|

1 |

Envelope 1 |

A |

VCO1 pitch |

|

2 |

Envelope 2 |

B |

VCO1 ultrasaw amount |

|

3 |

Envelope 3 |

C |

VCO1 pulse width |

|

4 |

Ext signal input envelope follower |

D |

VCO1 metalizer amount |

|

5 |

LFO1 |

E |

VCO2 pitch |

|

6 |

LFO2 |

F |

VCO2 ultrasaw amount |

|

7 |

LFO3 |

G |

VCO2 pulse width |

|

8 |

Modulation wheel |

H |

VCO2 metalizer amount |

|

9 |

Keyboard/Sequencer triggers |

I |

VCF1 cutoff frequency |

|

10 |

Aftertouch |

J |

VCF2 cutoff frequency |

|

11 |

Velocity |

K |

LFO1 amount |

|

12 |

The Sequencer Mod row |

L |

Audio signal VCA gain |

|

13 |

Macro knob 1 |

M |

Assignable |

|

14 |

Macro knob 2 |

N |

Assignable |

|

15 |

Macro knob 3 and Expression pedal 1 (summed) |

O |

Assignable |

|

16 |

Macro knob 4 and Expression pedal 2 (summed) |

P |

Assignable |

Hidden Commands

Although most of the MatrixBrute’s operation is self-evident there are (as far as I can ascertain) seven unannotated commands that you access via button combinations.

- Auto-tune Panel + VCO3/LFO3 Kbd Track

- Init voice Panel + PRESET

- Clear matrix Panel + MOD

- Reset sequencer pattern Panel + SEQ

- Reset knob’s value to zero (Macro knobs / Master Cutoff / MOD Amount) Panel + knob

- Set split point Voice MODE + desired key

- Set lower voice octave Voice MODE + Octave <- or ->

Pros

- It’s a powerful synthesizer and, once you get to grips with it, its flexibility is astounding.

- It rewards thoughtful programming and can sound superb.

- It has a full-size 49-note keyboard with velocity and aftertouch.

- It’s solid and feels well built, and you’ll look good playing it.

- It has an internal universal PSU. Whoo-hoo!

Cons

- The oscillators bleed quietly through VCF1.

- There’s no ring modulator or audio-frequency amplitude modulation.

- Umm... my mind has gone blank.

Summary

When I look at the prices being charged for some vintage analogue monosynths, it reminds me that many modern alternatives offer great value for money. You might prefer the ergonomics of, say, an original ARP Odyssey or a Roland SH5 but, on a ‘features per shekel’ basis, the MatrixBrute is streets ahead of either of them. It also sounds great. Its price means that, to an extent, it will remain an exclusive synth to own and use, but I think that Arturia have cracked it with this one. Now, can I stop typing and go back to playing please?

information

$1999