V Collection 8 introduces new instruments and completely reworks some old favourites.

In recent years, Arturia’s V Collection has grown into a substantial resource, with emulations of numerous monosynths, polysynths, samplers, pianos, organs and other keyboards, the original of any one of which (with the possible exception of the CZ1) would cost more than the whole collection. Today, V8 adds four new instruments as well as two upgraded ones, plus a new version of Analog Lab, new sound libraries and further enhancements including macros, improved housekeeping and integrated tutorials.

Before looking at the instruments themselves, I would like to discuss something that, in my opinion, Arturia never got right in the past. Introduced in the noughties, this was the company’s method of emulating the drift of analogue oscillators by applying a random offset to their initial phases when you played each note. If the synth in question used two oscillators per voice, the problems with this method were twofold. Firstly, if the oscillators were tuned to the same pitch, each note’s tone could be significantly different from the previous and the next. Indeed, if the oscillators’ phases happened to be 180 degrees apart, any given note could sound an octave higher than played. Secondly, there was no drift once the offset was applied. This meant that you obtained a collection of different, but tonally static notes when you played chords, no matter how long you held them.

Now let’s jump forward to last summer. Shortly after I reviewed Arturia’s OB‑Xa V (in SOS August 2020 issue) I received an email from the company’s engineers that described their new, ‘free‑running’ oscillator technology, as well as links to two prototypes that incorporated various implementations of this. Even at that stage it was clear that this was going to be a big step forward, so I was delighted when I heard that it was going to make its debut in V Collection 8 as part of an improved Jup‑8 V4 and the new Jun‑6 V. So that’s where we’ll start.

Jup‑8 V4

Turning first to the new version of Jup‑8 (shown above), the differences between V3 and V4 proved to be far more significant than I had expected. While the main row of synthesis controls remains largely unchanged, much else is so different that, not long after I started testing it, I decided that V4 is a different synthesizer rather than an update. In addition to the free‑running oscillator algorithm (which is invoked when the oscillators are independent and when they are sync’ed but, for mathematical reasons, not when cross‑mod is used) V4 also includes a new Voices Dispersion panel with four associated buttons. There are six dispersion parameters — oscillator pitch and pulse width, filter cutoff and resonance, contour time and modulation depth — and these allow you to determine the amounts by which each voice can differ from the others in each of these ways. The first three buttons allow you to select three factory preset degrees of variation, or you can program your own dispersion model and select this using the Custom button. Once programmed, the dispersions are constant because the developers found that adding further random variations to the amounts didn’t emulate the original behaviour, but they’ve told me that this is something that they are looking to model in the future.

To test the impact of these changes (and others that there’s no space to describe) I loaded Jup‑8 V3 and V4 simultaneously with the intention of creating identical patches on each and performing a few A/B tests. But I soon abandoned the experiment because there was no point; V4 sounds so much better than V3 as to make such comparisons pointless. After 14 years, Jup‑8 V4 is the soft synth that its predecessors had always promised to be. The sooner that Arturia ports these technologies to any other products that could benefit, the better!

Nonetheless, there are two caveats to Jup‑8 V4. Firstly, it’s not backward compatible so you’ll have to re‑program your existing patches, and some — such as those that used the now discarded Galaxy modulator — may no longer be possible. There are many new modulation features, many of which are very welcome, but Galaxy is gone. Secondly, V4 lacks the Split and Dual modes of its predecessors and its original inspiration. Would I revert to Jup‑8 V3 to retain these? No, not a chance... If I want to create split or layered Jupiter 8 sounds I will simply turn to Analog Lab V (see 'Analog' box).

Jun‑6 V

The other synth that uses the free‑running oscillator technology is a recreation of the Juno 6 — a synth of such devastating usability that it helped to define what an affordable synthesizer could (and should) be. Of course, the oscillator drift is not as apparent with a single oscillator per voice, but it nonetheless reveals itself in a natural sound when you play chords and, in a direct comparison with an original Juno, the soft synth almost always proved to be an adequate replacement. There are minor differences, and many will notice that the chorus isn’t quite the same (although settings I and II sound accurate in isolation, activating both simultaneously results in a slower ensemble modulation than on the original) but most sounds were as close to identical as makes no significant difference.

Jun‑6 V recreates the distinctive linear layout of the original.

Jun‑6 V recreates the distinctive linear layout of the original.

So why did I write “most sounds” rather than “all sounds”? It’s because the filter doesn’t track as well on the soft synth as it does on either of my Junos. Strangely, this is intentional; the Jun‑6 V manual even states that the original Juno’s filter doesn’t track perfectly across the whole width of the keyboard (which is wrong, because it does on both of mine). So I’m left to wonder why its designers reached that conclusion. Perhaps the unit on which they modelled Jun‑6 V was faulty or mis‑calibrated. But whatever the reason might be, the consequence is that some flagship Juno sounds can’t easily be recreated. My go‑to test patch on any Juno is an organ that uses the sub‑oscillator as the 16’ drawbar, the pulse wave as the 8’ drawbar, and the self‑oscillating filter as the 5‑2/3’ drawbar. It takes mere seconds to program this on the original synths because their filters immediately lock to the output from their oscillators in a very euphonic fashion and track perfectly across all five octaves. But it took me a long time to obtain anything approaching this on Jun‑6 V, and I had to experiment extensively with the sub‑oscillator level and the oscillator pulse width before I could approximate the original. If my Junos are typical (and I believe that they are) I think that Arturia should look at this again.

Inevitably, Jun‑6 V also adds much to the original Juno architecture, and you can access most of this by opening the Advanced panel to reveal performance assignments, a second LFO, a second ADSR contour generator, plus delay and reverb effects. You can select up to seven simultaneous modulation paths in this panel — one each for velocity, aftertouch and the mod wheel, plus two each for the LFO and ADSR — with each drawing from a list of 35 destinations. Unfortunately, you can’t send (for example) velocity to two destinations simultaneously to synthesize the increase in loudness and brightness that you obtain when you hit a physical thingy harder. But since you can’t do any of this on the Juno 6 itself I’m not going to criticise. There’s only one other thing that I’d like to note before moving on. If you sweep Jun‑6 V’s parameters using its faders, the results can be a bit granular — noticeably more so than on Jup‑8 V4. But when the same parameters are swept using the contours and LFOs everything is smooth, as it should be.

Emulator II V

As is obvious from its name, Emulator II V is an emulation of the Emulator II sampler/synth. But before proceeding to test this, I reminded myself why you can’t emulate an EII by sticking a bunch of resampled WAVs into a modern replay engine. This is because the Emulator’s sound was determined by some unusual algorithms that, while groundbreaking at the time, have long been replaced. It wasn’t just its unusual 27.7kHz sample rate; the sample values were determined by a non‑linear system that calculated differences rather than absolute values. Not only did this allow the EII to deliver a wider dynamic range and a lower noise floor than could be obtained from the same amount of data using a conventional PCM system, it also imparted a different sonic character than would otherwise have been obtained. So the first question for EII V is... does it recreate the ‘DPCM µ‑255 companding’ of the EII? Happily, it does. When you import audio, it’s converted into appropriate 8‑bit samples with a sampling rate of 27.7kHz. Then, when you save the results, they remain in this format. Upon replay, EII V recreates the EII’s decoding, passing the samples through a virtual DAC that imitates the original’s data expansion and anti‑aliasing features before the resulting audio reaches the emulations of its SSM filters and output stages. Aficionados of the EII will love this, but newbies who haven’t played a vintage sampler and expect everything in life to sparkle like 24‑bit, 96kHz recordings may wonder why it sounds as it does.

Emulator II V — considerably more portable than the original...

Emulator II V — considerably more portable than the original...

Now let’s turn to the practicalities. Whereas Arturia’s GUI is designed to give you the impression of an EII, it’s nothing like it... it’s much more usable. There was nothing particularly arcane about the EII, but you needed patience to obtain good results. In contrast, EII V brings the original’s analogue‑type facilities — LFO, filter and filter contour, amp and amp contour — to the front panel, adding to these a simple but useful arpeggiator plus level controls for the three effects slots tucked away in the Advanced panels. But if the basic synthesis controls were manageable on the original, sample manipulation was a bit of a nightmare. This was inevitable given the lack of a VDU, so it’s no surprise to find that the Edit, Assign and Effects screens of EII V’s virtual VDU simplify everything considerably. The same is true of the EII’s sequencer, which is much simpler here... because it’s been discarded. I approve. It would take a strange type of masochism to want to use this when you’re already running EII V on a modern computer.

EII V comes with an extensive sample library that includes much of the EII’s factory library, but only a subset of this has been used to recreate the original EII factory sounds. These include its Marcato Strings, the ‘Sledgehammer’ Shakuhachi, the marimbas and more, but if you want to recreate more of the original sounds, you’ll have to find the appropriate samples and program them yourself. There were also third‑party libraries for the EII, and you’ll find many .eii soundbanks online. Once downloaded, you can import these without difficulty but, while the samples’ start, loop and end points are interpreted correctly if they are present in the associated metadata, the rest of the patch information is not understood. This means that you’ll have to map the samples and reprogram the analogue part of the patch yourself. Apparently, the developers put a considerable amount of work into recreating the EII’s patch‑reading system but without success. They don’t discount the possibility for the future, but I suspect that a complete import capability may never appear.

So, how does it sound? I gave away my faulty EII many years ago and, at the time, I thought that I was happy to see the boat anchor disappear up the road. However, I’ve had a long time to learn to regret that decision, not least because I now have no way to compare EII V with the original. I suspect that it recreates its character well, but I must admit that it sounds cleaner than I remember. If true, this is not surprising. Even with the sample engine emulated correctly, EII V replaces banks of aging and unreliable analogue electronics with physical models, and the final output is through a nice, modern converter. Am I complaining? Not in the slightest. Quite the opposite, in fact, because I now have up to 32‑note polyphony, up to four effects per sound, and lots of other benefits. Oh yes, and EII V is much easier to use and great fun. What’s not to like?

Vocoder V

The collection’s Vocoder is styled upon Moog’s 16 Channel Vocoder, but with both enhancements and limitations when compared with the original. The most obvious enhancement is the attached polysynth that generates its carriers. This is just as well. Without it, Vocoder V would be silent because, despite appearing to have an external carrier input, its most obvious limitation is that this is just a graphic affectation.

Vocoder V offers a wealth of controls but no carrier input.

Vocoder V offers a wealth of controls but no carrier input.

I conducted my first tests using a sample as the modulator rather than live input, recording a short vocal and inserting this into the first of the 12 available slots within Vocoder V itself. I then set the start, loop and end points to create a glitch‑free sustained voice. Next, I turned to the integrated synthesizer to create the carrier, selecting a single oscillator to generate a narrow pulse wave and choosing suitable Attack and Decay settings. I then added a smidge of portamento to create a natural transition between notes, turned the ensemble effect to maximum, and inserted a reverb unit into one of the three effects slots to create suitable ambience.

Turning to the Vocoder section, I removed the patch cables, defeated the ‘straight through’ high frequency option, set the Hiss/Buzz setting to its default, and turned the output to 100 percent Vocoder. I then moderated the levels of the Synth (carrier) and Voice (modulator) to ensure that there was no distortion, and finally experimented with the Bands settings and their levels to obtain the formants and tones that I wanted. Within moments, the results that I obtained were sublime, with male and female solos and choirs just a few tweaks away, and (by accident) some of the best cellos I’ve ever synthesized. Of course, I didn’t stop there, and was soon obtaining a huge variety of effects ranging from intelligible vocal accompaniments to the Robots Of Doom. I also spent considerable time investigating the factory sounds because these illustrate how flexible Vocoder V can be. Many of these use drum loops at modulators, which is a great way to create rhythms, while others generate sounds reminiscent of polysynths, and I even discovered an enormous overdriven guitar effect that I liked very much.

Next, I inserted Vocoder V into Plogue Bidule because I wanted to discover its full range of I/O options. Three versions appeared, each with stereo inputs plus MIDI In and Thru, but a choice of two, six or eight audio outputs. In each case an extra, spurious audio output also appeared, but plugging this into anything defeated the entire audio system on my Mac. Treat Vocoder V as 2‑in/2‑out and you won’t go far wrong.

Having ascertained all of this, I carried on creating new sounds. I could cover pages describing how I did so and the results that I obtained. Vocoder V offers sample stretching, pitch tracking, time‑stretching, cross‑connection of the analysis and processing bands (including directing one analysis band to multiple processing bands), envelope following, freeze and more, so there’s way too much to discuss here. And that’s before we consider MIDI‑automated waveshaping of the carrier (ooh... I enjoyed discovering that), the modulation matrix, and the effects.

But I also have to emphasise the lack of a carrier input. I understand the technical reasons for this, but it’s still a significant shortcoming. The original Moog had one, as did other important vocoders such as the VP330, so I think that Arturia should consider recreating Vocoder V as a plug‑in effect as well as an instrument. The other niggle regarded the positions of the patch sockets for the bands. While they are accurate with respect to the Moog Vocoder, they can be a pain in the arse because, when you plug cables into them, they obscure some important controls. Perhaps it would have been wise to sacrifice some artistic accuracy to improve the user experience. Nonetheless, Vocoder V was the addition to V Collection 8 that most surprised and engaged me. There have been some fine digital vocoders released in recent years, but this one can be a bit special.

Stage‑73 V2

The final new synth in the Collection is OB‑Xa V but, since I’ve already reviewed this in depth, we’ll move on to the second major upgrade. This is an overhaul of Stage‑73, Arturia’s emulation of Rhodes pianos. As I did with Jup‑8 V3 and V4, I ran the original Stage‑73 V and the V2 upgrade simultaneously, and came to the same conclusion; Stage‑73 V2 isn’t so much an upgrade as a new instrument. You only have to look at the underlying technology to confirm this; whereas Stage‑73 V offered eight so‑called ‘Spectrum Profiles’, V2 has a new set of models, many of which align more obviously with specific incarnations of the Rhodes piano. Then there are the modifying parameters: hammer hardness, pickup distance and so on. Stage‑73 V had eight of these, whereas V2 has 12, losing damper distance but adding damper duration, damper noise, tine noise, pickup noise, and mono/stereo/room output modes.

Like the new version of Jup‑8 V, Stage 73 V2 has been completely reworked.Not only has the modelling been extended and improved, but the effects structure of V2 is also much more suitable. Stage‑73 V offered four effects slots that you could populate from a list of six effect types but with the limitation that you could invoke only one of each effect. The output from these could then be directed either straight to your output or through a Fender‑style amp model that included a spring reverb. Today, V2 has 13 effects types and you can insert these into the slots without restrictions upon choice. Furthermore, the output from these is fed to a dedicated amp slot offering both Fender Twin and Leslie emulations (with five models for the latter), and an additional Room slot offers nine reverb types ranging from a tight Spring and an EMT Plate to a Concert Hall and cavernous Abandoned Warehouse.

Like the new version of Jup‑8 V, Stage 73 V2 has been completely reworked.Not only has the modelling been extended and improved, but the effects structure of V2 is also much more suitable. Stage‑73 V offered four effects slots that you could populate from a list of six effect types but with the limitation that you could invoke only one of each effect. The output from these could then be directed either straight to your output or through a Fender‑style amp model that included a spring reverb. Today, V2 has 13 effects types and you can insert these into the slots without restrictions upon choice. Furthermore, the output from these is fed to a dedicated amp slot offering both Fender Twin and Leslie emulations (with five models for the latter), and an additional Room slot offers nine reverb types ranging from a tight Spring and an EMT Plate to a Concert Hall and cavernous Abandoned Warehouse.

The result is a Rhodes emulation that is more flexible and, I would suggest, more accurate than before. When played from a suitable keyboard (I used an 88‑note Korg Nautilus with the piano‑weighted RH3 keyboard used on the Kronos and others) it feels more authentic under my fingers, and I suspect that it will fool more listeners into believing that they’re listening to the ‘real thing’. Stage‑73 V was Rhodes‑y, but V2 is significantly Rhodes‑ier. I don’t think that you need hesitate to upgrade.

Conclusions

Arturia’s V Collection not only continues to grow, it continues to improve as older instruments evolve. (This is very much to the company’s credit because, while all manufacturers are willing to pay to develop new products, not all will invest similar resources to replace existing ones with upgrades.) When you add the investment in new factory sounds and new housekeeping systems, it’s clear that V Collection 8 represents a huge commitment in time, effort and cash.

Of course, it’s always possible to find arcane settings that reveal differences between the original instruments and the emulations, and some people will continue to revel in discovering them and then moaning endlessly online. But are they ever going to own a Jupiter 8, an OB‑Xa, a Moog Vocoder, a Juno 6, a Rhodes 88 and an Emulator II, let alone a CS80, a Synclavier, a Fairlight CMI IIx, an Oberheim 8‑Voice, and all the other goodies carried forward from V Collection 7? Be honest... it’s not likely. Ultimately, V Collection 8 is a remarkable collection and, at the current price of around £19$20 per instrument, it’s stunning value. Sure, there are niggles but, despite my critical faculties remaining fully functional, there are times when I just have to say ‘well done’.

Analog Lab V

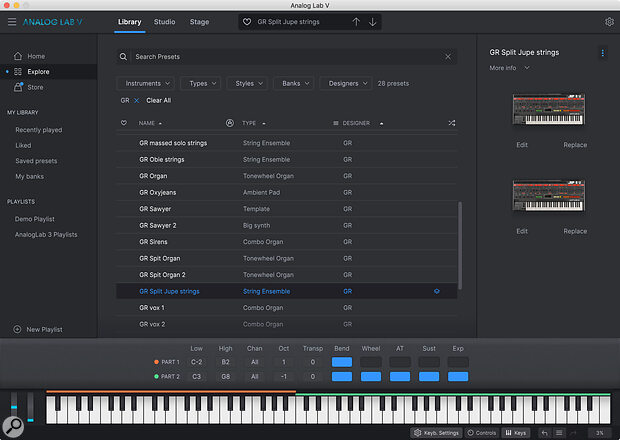

Analog Lab V's library screen.Also supplied with many of Arturia’s controller keyboards, Analog Lab V is stuffed full of sounds generated by the company’s soft synths and other keyboards. When installed in isolation, it allows a reasonable amount of editing but, when installed as part of V Collection 8, it allows you to edit every sound fully using the instrument that generates it. But this isn’t the limit of its abilities because this is also where you can create splits and layers of any two sounds generated within the collection, making it (for example) the mechanism by which you overcome the loss of the Split and Dual modes in Jup‑8 V4. Furthermore, it also provides direct access to Arturia’s shop, allowing you to buy new libraries — many with names such as Vangelis Tribute, Floyd Tribute and Genesis Tribute — from within the application. (Don’t worry, there are others named things like XT Grain, Future Tech, and Trance Delight if you’re less of a boring old fart than I am.) The first of these, named ‘Patchworks’, comes free with V Collection 8, and a handful of others can also be downloaded free of charge.

Analog Lab V's library screen.Also supplied with many of Arturia’s controller keyboards, Analog Lab V is stuffed full of sounds generated by the company’s soft synths and other keyboards. When installed in isolation, it allows a reasonable amount of editing but, when installed as part of V Collection 8, it allows you to edit every sound fully using the instrument that generates it. But this isn’t the limit of its abilities because this is also where you can create splits and layers of any two sounds generated within the collection, making it (for example) the mechanism by which you overcome the loss of the Split and Dual modes in Jup‑8 V4. Furthermore, it also provides direct access to Arturia’s shop, allowing you to buy new libraries — many with names such as Vangelis Tribute, Floyd Tribute and Genesis Tribute — from within the application. (Don’t worry, there are others named things like XT Grain, Future Tech, and Trance Delight if you’re less of a boring old fart than I am.) The first of these, named ‘Patchworks’, comes free with V Collection 8, and a handful of others can also be downloaded free of charge.

Users of earlier versions will need a while to become accustomed to Analog Lab V because many of its screens have been updated to accommodate new features. Furthermore, the number of initial sounds supplied with it has been reduced from the 6500 that accompanied Analog Lab 4 to just 2000. Happily, I found that all of my existing Analog Lab 3 and Lab 4 sounds appeared alongside the new ones in Lab V, giving me a total of 12,181 presets even before I started creating new ones. However, there’s a caveat: the effects structures of Analog Lab 3 and Lab 4 are different from that in Lab V, so any older presets imported into the new version will lose their effects. If you want to obtain the same sounds as before, you either have to reprogramme these or run multiple generations of Analog Lab simultaneously, which, when tested, proved not to be a problem. In truth, I have no problem with this. At some point, software manufacturers have to break with the past to provide improvements, especially as any associated hardware evolves. If some effects are the only casualties of this, I don’t think that’s too high a price to pay. Now, when are Arturia going to make Analog Lab eight‑part multitimbral? Surely that’s got to be the next step?

Arturia’s V Collection not only continues to grow, it continues to improve as older instruments evolve.

Pros

- The new instruments are well chosen and sound great.

- The updates to the Jupiter 8 and Rhodes piano emulations represent huge improvements.

- At less than £20 per instrument, the collection is excellent value.

Cons

- There are some niggles and limitations, but none of these should be deal‑breakers.

Summary

When it comes to a one‑stop source of instruments covering almost all of the bases, I’m not aware of anything else that offers either the scope or the ambition of V Collection 8. I’m excited to see what Arturia will add next.