This debut product from a new British company is not just another mic preamp...

Cranborne Audio are a new British company set up by a small group of bright young product designers, all of whom share a determination to build products they want to use themselves, and to build them ‘the right way’, with no shortcuts, and no compromises. One of their most audacious aims is to “deliver ground‑breaking performance, with UK manufacturing at prices that will surprise everyone”. It’s quite a game plan, but Cranborne are off to a very good start with their debut product, the 500‑series preamp I’m reviewing here, and there’s a pair of very impressive, innovative 500‑series racks about to go into production too: the 500R8 doubles up as a multi‑channel USB audio interface, and the 500ADAT features bi‑directional analogue‑to‑ADAT conversion. Both racks boast other interesting features too, including a summing mixer and monitoring facilities.

Cranborne Audio are a new British company set up by a small group of bright young product designers, all of whom share a determination to build products they want to use themselves, and to build them ‘the right way’, with no shortcuts, and no compromises. One of their most audacious aims is to “deliver ground‑breaking performance, with UK manufacturing at prices that will surprise everyone”. It’s quite a game plan, but Cranborne are off to a very good start with their debut product, the 500‑series preamp I’m reviewing here, and there’s a pair of very impressive, innovative 500‑series racks about to go into production too: the 500R8 doubles up as a multi‑channel USB audio interface, and the 500ADAT features bi‑directional analogue‑to‑ADAT conversion. Both racks boast other interesting features too, including a summing mixer and monitoring facilities.

Clearly, setting up a brand‑new audio‑equipment company is not for the faint‑hearted, but this team has a wealth of previous experience, gained mostly from working at Soundcraft, where they developed products including the Signature, Ui and Si series of mixing consoles.

The Camden Concept

An Audio Precision plot of the preamp’s frequency response with the high‑pass filter switched in and out. (The fuzziness at the very high‑frequency end of the plot is an irrelevant measurement artifact.) With the HPF switched out, the response is ruler‑flat from 10Hz to well over 80kHz (within 1dB), and ‑3dB at 7Hz. With the HPF switched in, the low end is rolled off initially at around 6dB/octave but increasing to 12dB for the lowest octave.Pretty much all 500‑series module manufacturers offer a mic preamp of one sort or another, and that’s not surprising, since a mic preamp is the logical place to start — the first job is to get audio into a recording system! That said, the Camden 500 is not just another ‘me‑too’ mic preamp. Designed from the ground up with some genuine innovation, this preamp offers supreme technical precision and high‑end transparency, but also attractively characterful recordings, courtesy of the ability to tune and shape the recording as the situation demands.

An Audio Precision plot of the preamp’s frequency response with the high‑pass filter switched in and out. (The fuzziness at the very high‑frequency end of the plot is an irrelevant measurement artifact.) With the HPF switched out, the response is ruler‑flat from 10Hz to well over 80kHz (within 1dB), and ‑3dB at 7Hz. With the HPF switched in, the low end is rolled off initially at around 6dB/octave but increasing to 12dB for the lowest octave.Pretty much all 500‑series module manufacturers offer a mic preamp of one sort or another, and that’s not surprising, since a mic preamp is the logical place to start — the first job is to get audio into a recording system! That said, the Camden 500 is not just another ‘me‑too’ mic preamp. Designed from the ground up with some genuine innovation, this preamp offers supreme technical precision and high‑end transparency, but also attractively characterful recordings, courtesy of the ability to tune and shape the recording as the situation demands.

The ‘characterful’ aspect comes from Cranborne’s new Mojo system, which comprises a set of bespoke filters and harmonics generators. These work in concert to replicate the kind of subtle and often desirable characteristics of the input transformers in traditional mic preamps. This combination of ultra‑linear, very high‑performance, transformerless preamp with the user‑controllable Mojo saturation makes the Camden 500 preamp an attention‑grabbing and extremely versatile design.

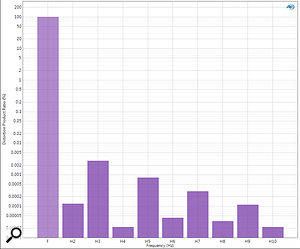

Bypass, min and max plots. This trio repeats the range for the Thump setting, with the underlying distortion when bypassed, followed by the min and max control settings. Here the amount of harmonic distortion is much lower, and mostly a balanced level of second and third harmonics.

Bypass, min and max plots. This trio repeats the range for the Thump setting, with the underlying distortion when bypassed, followed by the min and max control settings. Here the amount of harmonic distortion is much lower, and mostly a balanced level of second and third harmonics.

On a technical level, this preamp’s front‑end is unlike anything I’ve encountered in a 500‑series module. A novel design, it has an elaborate input stage built with discrete transistors, and seems more complicated than most, although it’s apparently based on the double‑balanced current‑feedback topology that’s used widely in high‑end consoles and preamps. It was optimised from the outset for the restricted power rails of the 500‑series format, rather than being modified from a high‑voltage design. The end result is a gain stage that delivers a consistent and extremely wide bandwidth at all gain settings, with a very high open‑loop gain to ensure very low distortion, while also maintaining the kind of common‑mode rejection (including at RF) normally achieved only with transformer‑coupled designs. I measured over 80dB CMRR at 20kHz (with a 100mV test signal and 35dB of preamp gain), falling to about 65dB CMRR at maximum gain. That’s impressive!

On a technical level, this preamp’s front‑end is unlike anything I’ve encountered in a 500‑series module. A novel design, it has an elaborate input stage built with discrete transistors, and seems more complicated than most, although it’s apparently based on the double‑balanced current‑feedback topology that’s used widely in high‑end consoles and preamps. It was optimised from the outset for the restricted power rails of the 500‑series format, rather than being modified from a high‑voltage design. The end result is a gain stage that delivers a consistent and extremely wide bandwidth at all gain settings, with a very high open‑loop gain to ensure very low distortion, while also maintaining the kind of common‑mode rejection (including at RF) normally achieved only with transformer‑coupled designs. I measured over 80dB CMRR at 20kHz (with a 100mV test signal and 35dB of preamp gain), falling to about 65dB CMRR at maximum gain. That’s impressive!

Like many 500‑series preamps, the Camden features a front‑panel quarter‑inch input socket which can be switched to accept a balanced line or unbalanced instrument source. Many preamps with this feature use a simple FET buffer to provide the high‑impedance input, but in developing the Camden, Cranborne felt a more complex bipolar junction transistor circuit gave a “more muscular tonality”. The input impedance of this unusual design is still a high 1.5MΩ.

Controls

The single‑width front panel looks very open and uncluttered, with clear light‑grey legends on a black background. The instrument/line input socket, which sits right at the bottom of the panel, overrides the rear XLR when something is plugged in. Two toggle switches above select phantom power (rear XLR only) and the input source mode (mic, line or high‑impedance instrument).

A 12‑way rotary switch adjusts the preamp gain in nominally 5.5dB steps across a 60dB range. This gain range is available in all three input modes, but changing the mode alters the input attenuation and thus headroom margins to suit the source. This rotary switch has a nice solid feel, and completely avoids gain‑bunching at the loud end, which is a perennial problem with ordinary potentiometer gain controls.

Two more toggles invert the output polarity and engage the high‑pass filter, raising the ‑3dB roll‑off point from 7Hz when bypassed to 80Hz when active. The published specifications claim a 12dB/octave slope, however the reality is a little more complicated, given that the filter slope is progressive. In the octave below 80Hz the slope is about 6dB/oct, but it then gets steeper as the frequency decreases, reaching 12dB/oct in the octave below 5Hz. The main advantage of this approach is that it minimises phase‑shift — and one of the core strengths of the Camden 500 preamp is its near‑zero phase shift across the entire audio bandwidth. A second benefit is that unwanted, destructive sub‑sonics are attenuated to a useful degree, but genuine LF musical components are retained at a higher level, and can contribute to the harmonics generated by the Mojo system.

A measurement of the phase response of the Camden 500 with the HPF switched in and out (and no Mojo). With the filter bypassed the phase response is very linear, amounting to less than +4 degrees at the extreme LF, and gradually building to ‑10 degrees at 20kHz. Switching the HPF in necessarily adds a lot of low‑end phase shift, but it is still less than 100 degrees at 20Hz.Sitting right at the top is the Mojo section, comprising another toggle and a rotary control with a switched backstop. The toggle selects between two tonalities, ‘Thump’ and ‘Cream’, while the knob sets the strength of the harmonics generation. This combination can create a wide variety of saturation effects, but when not required the Mojo system is bypassed completely by turning the knob fully counter‑clockwise to activate the backstop switch. Two LEDs indicate signal presence (green) with variable brightness, and impending clipping (red).

A measurement of the phase response of the Camden 500 with the HPF switched in and out (and no Mojo). With the filter bypassed the phase response is very linear, amounting to less than +4 degrees at the extreme LF, and gradually building to ‑10 degrees at 20kHz. Switching the HPF in necessarily adds a lot of low‑end phase shift, but it is still less than 100 degrees at 20Hz.Sitting right at the top is the Mojo section, comprising another toggle and a rotary control with a switched backstop. The toggle selects between two tonalities, ‘Thump’ and ‘Cream’, while the knob sets the strength of the harmonics generation. This combination can create a wide variety of saturation effects, but when not required the Mojo system is bypassed completely by turning the knob fully counter‑clockwise to activate the backstop switch. Two LEDs indicate signal presence (green) with variable brightness, and impending clipping (red).

Find My Mojo

I gather the Mojo saturation circuit started out as a research project, examining what makes transformer‑based preamps sound the way they do. It involved measuring a number of popular input transformers (from Carnhill and Cinemag, amongst others) to assess the low‑end equalisation effects, harmonic distortion and phase‑shift they introduced in a scientific way. Armed with this information, the team set about designing bespoke harmonic generation and filtration circuitry to recreate these effects.

A selection of frequency responses at different Mojo settings. The Thump mode results in the peaking LF and HF boosts, centred around 20Hz and 10kHz, with up to 9dB of boost at the low end and 2dB at the high end. The Cream mode introduces a progressively deep notch filter centred at 500Hz. These filter responses are applied in addition to harmonic generation.Key amongst the benefits of emulating the sonic characteristics of transformer‑based preamps in this way is the near‑infinite control and almost unlimited saturation, which simply wouldn’t be possible with a conventional transformer front‑end. In the Camden 500 implementation, the Mojo circuitry is continuously variable, and the effects range from the subtlety of a high‑quality modern transformer to the heavier and thicker sound of a classic vintage design, and then far beyond into saturation levels that would result in severe clipping in a traditional transformer preamp. The Thump and Cream modes also tailor the saturated sound in different ways, for even more versatility. And bypassing the Mojo circuitry leaves an ultra‑clean and transparent preamp for those situations where total clarity and neutrality are called for.

A selection of frequency responses at different Mojo settings. The Thump mode results in the peaking LF and HF boosts, centred around 20Hz and 10kHz, with up to 9dB of boost at the low end and 2dB at the high end. The Cream mode introduces a progressively deep notch filter centred at 500Hz. These filter responses are applied in addition to harmonic generation.Key amongst the benefits of emulating the sonic characteristics of transformer‑based preamps in this way is the near‑infinite control and almost unlimited saturation, which simply wouldn’t be possible with a conventional transformer front‑end. In the Camden 500 implementation, the Mojo circuitry is continuously variable, and the effects range from the subtlety of a high‑quality modern transformer to the heavier and thicker sound of a classic vintage design, and then far beyond into saturation levels that would result in severe clipping in a traditional transformer preamp. The Thump and Cream modes also tailor the saturated sound in different ways, for even more versatility. And bypassing the Mojo circuitry leaves an ultra‑clean and transparent preamp for those situations where total clarity and neutrality are called for.

Bench Pressing

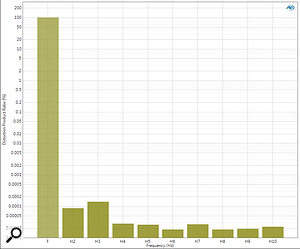

Bypass, min and max plots. This trio of plots shows the underlying harmonic distortion make‑up of the preamp (bypass), and the harmonic distortion in the Cream mode at minimum and maximum settings. Note the strong and predominantly odd‑order harmonic generation.

Bypass, min and max plots. This trio of plots shows the underlying harmonic distortion make‑up of the preamp (bypass), and the harmonic distortion in the Cream mode at minimum and maximum settings. Note the strong and predominantly odd‑order harmonic generation.

As usual, I ran a series of technical bench tests to assess the Camden 500’s technical performance using an Audio Precision test set. The mic input impedance was a little higher than most — often a good thing — at 5.4kΩ, rising to nearly 9kΩ when phantom power is switched off. In line mode, the input attenuator raises the impedance to around 25kΩ, while the instrument input is 1.5MΩ, as mentioned earlier (3MΩ if the instrument has a balanced output).

As usual, I ran a series of technical bench tests to assess the Camden 500’s technical performance using an Audio Precision test set. The mic input impedance was a little higher than most — often a good thing — at 5.4kΩ, rising to nearly 9kΩ when phantom power is switched off. In line mode, the input attenuator raises the impedance to around 25kΩ, while the instrument input is 1.5MΩ, as mentioned earlier (3MΩ if the instrument has a balanced output).

In mic mode, the preamp accepts a maximum signal of 17.5dBu, which is a very generous headroom margin and obviates any requirement for an input pad in normal applications. In line mode the maximum input level rises to +26.5dBu, while the instrument mode’s +24dBu is far more than any hot guitar pickup or active bass could manage.

While the preamp always provides a 60dB gain range, the different input attenuations adjust the minimum and maximum gains between +8 and +68 dB for the mic mode, +3 to +63 dB for the instrument input, and 0 to +60 dB for line. The maximum output level is at least +26.5dBu, and slightly higher with modest gain settings.

Equivalent input noise (EIN) for the mic input at full gain is a near‑perfect ‑129.5dB, unweighted (with a 150Ω source, 20Hz‑20kHz bandwidth), and the frequency response is a flat line (better than ±1dB) from below 10Hz to well beyond the 80kHz limit of my Audio Precision test set. Moreover, that flat‑line response really doesn’t vary at all with different gain settings — some lesser designs exhibit a curtailed LF and/or HF response as the gain is increased. Checking the distortion characteristics revealed that the THD (total harmonic distortion) and IMD (intermodulation distortion) are vanishingly small at less than 0.0007 and 0.002 percent, respectively. Phase shift measured below 10 degrees across the entire audio bandwidth, just over +1 degree at 10Hz, building to ‑10 degrees at 20kHz — so there’s genuinely negligible low‑end phase shift.

In Use

I was immediately attracted to the Camden 500 because of its spacious, simple front‑panel layout, and when I discovered the switched gain control I was smitten. But after listening to it and experimenting with the Mojo facility, I was completely sold. This really is a very impressive new preamp — both from the point of view of its sonics and the physical experience of adjusting the controls. The chunky toggles and commodious front panel make it a breeze to use, while the switched gain knob allows accurate adjustment without gain‑bunching. Importantly, there’s always masses of headroom whatever input configuration is selected, and it really excels as a clean, quiet, transparent, high‑quality preamp. It performed admirably alongside my Focusrite, SSL and GML preamps, for example, but it also sounded great as a DI for my passive bass.

In situations where an intentionally characterful sound is required, especially on instrument inputs, the Mojo system performs a wonderful Jekyll and Hyde act, bringing a surprisingly broad range of varied colour to the party in a very controllable way, although I found the preamp has to be driven reasonably hard to extract the full range of effects. The ability to apply these effects to your choice of mic, instrument or line‑level sources opens the door to some very interesting production options. It worked extremely well to add body and bite to my bass, and some colour and grit to my Korg MS20 monosynth, for example.

The Thump and Cream switch alters both the tonal balance and density of the effects in a complex but musical way, going far beyond simple EQ. Thump tends to thicken and fill out the low end, adding emphasis and power to this spectral region without making it woolly or muddy in the way that simple bass EQ often does. The effect starts out as a subtle ‘thickness’ and weight that’s similar to a vintage transformer, but as the Mojo control is increased the effect becomes stronger and warmer, extending into the mid‑range and softening the high end. In contrast, the Cream mode affects the mid‑range and high end a little more, adding an almost exciter‑like brightness to the high end. Towards the extreme end of the dial, the character approaches that of overdriven analogue tape, squashing transients and dynamics. Of course, as the Mojo harmonic generators rely on the source material’s spectral content, the character and strength of the effect can vary significantly with the source — but I usually found a setting that provided something musically interesting.

Camden Market

If you’re in the market for a high‑quality multi‑purpose preamp, the Camden 500 is a strong candidate. In its ‘clean’ mode it holds its head up confidently in the company of serious high‑end products, but it can also deliver convincing vintage character at the turn of a knob and the flip of a switch. That it’s British‑designed and built to very high standards, looks attractive, feels great to use, and is priced very competitively make this a very impressive first offering from Cranborne Audio. In short, this is how I’d design and build a quality preamp! I really can’t wait to see what else will emerge from this stable in the near future.

Alternatives

There are far too many preamps to mention even in the 500 series alone, but few are this well built or designed, few sound this clean and quiet, and very few have this much sonic versatility.

Pros

- Switched gain knob means precision and no gain-bunching.

- Masses of headroom and wide gain range.

- Front-panel DI input.

- Hugely versatile; very clean, but able to add Mojo saturation to taste.

- British designed and built to very high standards.

Cons

- None.

Summary

This elegant, very high-quality 500-series mic preamp compares favourably in its technical performance with high-end units, while also offering a wide range of controllable saturation effects.