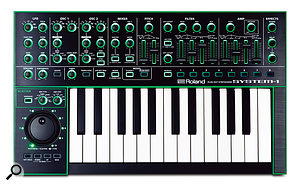

The System 1 is a fully fledged synthesizer in its own right, but it can also assume the identity of Roland classics using its built–in ‘plug–out’ technology.

Trailing slightly behind the forerunners of the Aira range, Roland’s eagerly anticipated System 1 is here at last. Its grand web site introduction refers back to the System 100, 100M and 700 modulars, although other than a broad remit to be flexible and sound ‘like Roland’, the connection isn’t obvious. Though the System 1 might be modular under the covers, its base personality is as a four–voice virtual analogue synthesizer driven by the technology known as Analogue Circuit Behaviour.

Unlike the TR8 and TB3, there’s been no attempt to replicate the sonic nuances of a specific favourite from the word go. Instead, modelled classics are planned later down the line as ‘plug–outs’, with the SH101 available first as a free download for System 1 owners. Other than the option to reside in hardware, a plug–out acts just like a regular plug–in.

Since I had a few weeks with the System 1 before the software SH101 hit the streets, I’ll begin there. It’s a credible stand–alone instrument in its own right, and one of the smallest, lightest and greenest four–voice synths ever.

Green Machine

Powering up the System 1, you’re blasted with more green than the combined exhalations of Snoop Dogg, Willie Nelson and Woody Harrelson. All the knobs, sliders and buttons are backlit and, as far as I can tell, there’s no way to turn off the eerie glow if it gets overpowering. Thankfully, it is possible to deactivate the vomit–inducing ‘LED demo mode’ in which the synth shimmers like the Green Goblin on acid if not touched for a while.

The controls are of good quality and, with no display or screen, multi–functionality is almost entirely absent. The layout is in traditional ‘signal flow’ order but fans of Roland’s other tradition — the combined bender and mod lever — will be disappointed it isn’t present. In its place is a sprung rotary control encircling an alpha dial. This mechanism has a choice of two modes — pitch–bend or ‘Scatter’ — but it’s hard to see how anyone would rate it as an improvement. Modulation suffers too, reduced to a single on/off button.

The System 1 is petite and wafer thin (472 x 283 x 70 mm) and its black plastic body tips the scales at 2.4kg. Matching the other Airas’ tapering style, the green–framed panel slopes to a slightly smaller base and the whole thing is so portable it’s a shame batteries were not an option. In a frame as compact as this one, it always seems to be the keyboard that bears the brunt of the compromises. Here it’s just two octaves long. In its favour, the keyboard is full–sized, but the keys are of the ‘minimal travel’ type seen on certain MIDI controllers. For me, this action falls way short of even the lowliest monosynth of Roland’s glory years. To further limit its capacity to delight, the keyboard generates neither velocity nor aftertouch. These are received over MIDI by the System 1 but both are interpreted as vibrato, which is a bit uninspired.

The rear panel’s only surprise is its lack of an audio input. This is doubly unfortunate given that the USB port can serve, in common with the other Airas, as a 24–bit audio (and MIDI) interface. There are conventional MIDI In and Outs too (the latter capable of soft Thru if necessary) and if the brace of control inputs seem like expressive overkill, don’t get too excited. The expression input is tied to controlling volume and the brief manual offers no hint of alternate options — or any clue about swapping the hold pedal’s polarity. There’s an external power supply, which is small and innocuous. Last but not least, the main output is stereo. This could be a choice that was more about the audio interface functionality because the synth lacks voice panning or a stereo chorus and the delay is currently mono.

We Come 1

Roland grab a handful of brownie points from the word go for producing a panel so logical and welcoming. Die–hard synth enthusiasts should be pleased by the carefully selected spread of knobs, sliders and buttons sitting comfortably together despite the small footprint. Even though the System 1 has eight patch memories, it usually made sense to work directly with the panel, which was a pleasant reminder of simpler times.

The System 1’s rear panel features an input for the external power supply, an on/off switch, a USB B port, MIDI Out and In, and, all on quarter–inch jack sockets, inputs for pedal and control, stereo audio out and a headphone port. Before I mist up, let’s explore this, the most recent incarnation of ACB and the first ‘full synth’ built using the technology. The System 1 has two oscillators, a sub oscillator and a noise generator; these are mixed then processed by a low– and high–pass filter. The waveforms are the expected analogue regulars, but in both single and doubled versions. Further modification comes from the ‘Color’ knob, which adjusts the square wave’s pulse width, the sawtooth’s phase and adds extra harmonics to the triangle. When you select a doubled waveform, Color sets modulation speed, plunging you straight into fuzzy ‘VA’ Supersaw, Supersquare or Supertriangle territory. The amount of Color can be modulated too, by sources that include the three envelopes, the LFO and the sub oscillator. This latter is more radical in theory than reality, or at least I found it unexpectedly subdued, but there’s no doubt Roland have dished up an effective system for squeezing the most tonal juice from very few controls.

The System 1’s rear panel features an input for the external power supply, an on/off switch, a USB B port, MIDI Out and In, and, all on quarter–inch jack sockets, inputs for pedal and control, stereo audio out and a headphone port. Before I mist up, let’s explore this, the most recent incarnation of ACB and the first ‘full synth’ built using the technology. The System 1 has two oscillators, a sub oscillator and a noise generator; these are mixed then processed by a low– and high–pass filter. The waveforms are the expected analogue regulars, but in both single and doubled versions. Further modification comes from the ‘Color’ knob, which adjusts the square wave’s pulse width, the sawtooth’s phase and adds extra harmonics to the triangle. When you select a doubled waveform, Color sets modulation speed, plunging you straight into fuzzy ‘VA’ Supersaw, Supersquare or Supertriangle territory. The amount of Color can be modulated too, by sources that include the three envelopes, the LFO and the sub oscillator. This latter is more radical in theory than reality, or at least I found it unexpectedly subdued, but there’s no doubt Roland have dished up an effective system for squeezing the most tonal juice from very few controls.

The pursuit of classic features continues with cross mod, ring mod and oscillator sync. Of these, cross mod is often a tough test for modelling technology. Admittedly, it fails to convince here if pushed towards its maximum values, but when used sparingly, the results are interestingly hard and cold. Cross mod is invaluable for synthesizing brittle, metallic tones, just don’t expect to hear the analogue rawness of, for example, a Jupiter 6.

The ring modulator is a doorway to bell–like oddness, discordant celestas, chimes and so forth. To unleash the ring mod’s wildest harmonics, you’ll need to find the hidden (and fortunately documented) coarse tune of oscillator 2. With no knob to turn directly, it’s a two–handed operation involving holding the Ring and Sync buttons then setting the interval using the Scatter dial. I’d also recommend trying ring mod and cross mod simultaneously, especially if you’re into spiky, fractured distortion and digital weirdness. Strangely, there’s no master tune control, so it’s A=440Hz all the way.

When oscillator sync is active, the second oscillator is slaved to the first. At the same time, the two–stage pitch envelope switches only to the slave. Increase the envelope depth and the resulting sync is creamy and very usable, if never quite matching the lusty scream of a genuine analogue synth. However, those lush multiplied waveforms should already have been a clue that the oscillators are not the result of obsessive analogue modelling. Diva this is not! It hardly matters because they sound fine and in particular have a deep and full bass end. The digital wonkiness is only really noticeable at higher pitches (4’ and 2’), where a background distortion creeps in.

If the oscillators are more VA than ACB, the filter fares much better. It is switchable between 12 or 24 dB operation and has a dedicated (and snappy) ADSR envelope. I was quickly won over by its wide sweeps, squelches and Virus–like smoothness. It’s true that at high resonance you risk a broadside from a powerful whistle, but generally the resonance has a character reminiscent of Roland’s SH1 synth, which is no bad thing. In another similarity to the SH1, there’s a dedicated high–pass filter with a single cutoff control. Bi–polar controls for envelope amount and keyboard tracking round off what could be Roland’s best analogue–modelled filter to date. For post–filter sound–shaping, a tone control offers a simple but effective boost of treble or bass.

The plug–out SH101’s interface. The three envelopes all work as they should, with no frills added or necessary. Ditto for the single LFO. Amongst its six waveforms, you’ll find sample and hold and the smoother ‘sample and glide’ — it lacks only noise to have the full set. The LFO’s fade–in time is programmable, which is particularly important when you’ve only got a button for modulation. It’s your choice whether the LFO is free–flowing or reset each time a key is pressed. At its top speed, modulation creeps into the low audio rates but isn’t quite fast enough for ripping excesses. Actually, I was more disappointed that its speed wasn’t marked by a flashing knob, as per the Tempo control. Three bi–polar knobs set the modulation amount of the pitch, filter and amplitude.

The plug–out SH101’s interface. The three envelopes all work as they should, with no frills added or necessary. Ditto for the single LFO. Amongst its six waveforms, you’ll find sample and hold and the smoother ‘sample and glide’ — it lacks only noise to have the full set. The LFO’s fade–in time is programmable, which is particularly important when you’ve only got a button for modulation. It’s your choice whether the LFO is free–flowing or reset each time a key is pressed. At its top speed, modulation creeps into the low audio rates but isn’t quite fast enough for ripping excesses. Actually, I was more disappointed that its speed wasn’t marked by a flashing knob, as per the Tempo control. Three bi–polar knobs set the modulation amount of the pitch, filter and amplitude.

Thanks For The Memories

The System 1 was shaping up as a powerful and full–featured synth for its size, and with programming so inviting it should take no time at all to populate the eight on–board patch memories. While this number is far from generous, it’s better than none, and whenever you need the panel to be live, the Manual button is your friend. Sequencer users will no doubt be glad of the ability to send the current patch data as a burst of MIDI CCs.

If Roland are stingy when it comes to patch memories, they’re positively miserly when doling out polyphony. Four notes doesn’t seem like a lot for a 21st Century modelled analogue synth in dedicated hardware, but maybe the short keyboard implies monophonic operation is the main goal. For extra mono oomph, there’s a unison mode that stacks the four voices on top of each other. I should also mention the legato button that, in mono and unison modes, ensures the envelopes aren’t retriggered by legato playing. Similarly, the same button ensures portamento is engaged only when notes overlap.

Mad Scatter

No Aira family member has yet been spared a Scatter function and here its purpose is to perk up the otherwise plain vanilla arpeggiator. Without Scatter you’d be left with just up, down, or up and down motions over one or two octaves. Bereft of more wayward directions (such as random), Scatter’s preset patterns are invaluable for adding variety. Since the wheel imposes a choice of either Scatter or pitch–bend, you can’t bend an active arpeggio as you can on other Roland synths (for example, the SH101).

Having selected a clock division (from 1/4 up to 1/16 T), you choose a Scatter type by spinning the inner alpha dial. Taking type 1 as an example, turning the outer wheel clockwise doubles the arpeggio speed. It also introduces modulation of both low– and high–pass filters and adds cross modulation. The affected controls flash to indicate they’re being manipulated. In contrast, turning the same wheel anti–clockwise drops the arpeggio to half–speed and introduces comparable tonal mangling. Since the wheel is sprung, the hold button can be used to freeze any particular favourite setting en route, which is a thoughtful touch.

If you aren’t careful, turning the outer wheel can accidentally move the inner one too, selecting a scatter type you didn’t bargain for.

Effects

After the simple tone control, the System 1’s output is finished off with ‘crusher’, reverb and delay. Crusher is a bit–rate reducer that seemed rough and more than a little out of place, especially when a classic Roland chorus emulation or modelled overdrive would have fitted so well. The reverb is better though; a reasonably expansive stereo hall that’s going to come in handy. The delay offers two controls — amount and time — and when Tempo Sync is active, it helpfully locks to divisions of tempo or incoming MIDI clock. Triplets are included but dotted delays are not. With no display of delay values, you must locate each time division by ear, but this is hardly an issue. More limiting is the lack of a dedicated feedback control, although the preset values are perfectly serviceable. The delay is mono and if further options lurk under the covers waiting to be exploited, there’s no information yet. Incidentally, Tempo Sync applies to the times of both the LFO and the delay: you can’t choose one or the other.  The System 1’s front panel is desktop friendly, measuring just 472 x 283 mm.

The System 1’s front panel is desktop friendly, measuring just 472 x 283 mm.

Plug–out

As mentioned already, a plug–out operates like a regular plug–in, but with the twist that it can be transmitted to the System 1. From that point onwards it can be accessed from hardware without need of a computer connection. Alternatively, no hardware is required to play the software synth in your DAW. Roland have opted for VST3 and AU support so far, so if you rely on VST or RTAS, plug–outs are currently off the menu. The pre–release version I started with was only compatible with Logic Pro X, but this was later extended to encompass 32–bit AU for older versions. Hopefully this widening of scope will continue.

Only one plug–out can be hosted in hardware at once. Taking into account the System 1’s own synth engine, you’ll therefore always have two choices.

The only plug–out available at the time of writing is Roland’s SH101, an acid plastic classic and one of my personal ‘desert island’ synths. It should also be a sporting challenge for ACB technology. After all, it’s an uncomplicated single–oscillator design with mixable waveforms, noise and a sub oscillator. Yet thanks to a near–perfect interface, fast envelope, Curtis oscillator and chirpy resonant filter, the 101 is still highly desirable today.

Having loaded the plug–out and fired it up in Logic, I performed the online activation and then took a few moments to transfer the code to the System 1. At transfer time, the first eight patches are also sent, although these may be transmitted and received later individually. Having the SH101 in software means you can maintain a large library of patches despite the limited amount of storage in the System 1 itself.

Running the plug–out as a 64–bit Audio Unit, I quickly stacked up 10 instances without troubling my Mac Pro in the slightest. I was glad to discover that several coloured skins were available. These are ideal for differentiating between multiple copies. The System 1 worked seamlessly as a controller for every SH101 instance during the review period, but as all its controls spurt MIDI it could serve equally well for other plug–ins.

It was while waiting for the SH101 plug–out to appear that I’d come across confident claims from Roland such as: ‘perfect replica’, ‘complete reproduction’ and ‘right down to the fine details and odd quirks’. Imagine my surprise, therefore, on trying the virtual SH101 for the first time, to find no sequencer was present. This is obviously some strange usage of the term ‘complete reproduction’ that I wasn’t previously aware of.

Actually, a number of other differences were soon obvious. I would hardly take issue with the provision of an extra envelope even if it does slow down the programming of typical 101 patches. Nor do I have a problem with the extra LFO waveforms, or that the System 1’s effects are retained — you can always ignore them. Looking closer, you realise that the modulation amounts are like those of the System 1 — bi–polar — which isn’t particularly 101–like. Worse, this effectively halves the knob’s resolution. Next I realised that the arpeggiator isn’t the same either. On the original, it only becomes active when you hold more than one note — not so on the plug–out version. I also missed the sliders that are used to assign pitch and filter cutoff modulation to the bender. However, these are small beer compared to the missing sequencer.

The SH101’s sequencer is wonderful. Requiring just four buttons to program and play it, it’s an accessible step sequencer with a capacity of 256 notes. Introduce rests and slides, add transposition from the keyboard, and you’ve got the classic recipe for enough SH101 patterns to last a lifetime. To imagine a perfect replica without the sequencer is nothing short of perverse.

Once my sulk had run its course, I got down to the serious business of audio comparisons, with the old and new synths placed side by side. Having pressed the Plug–out button on the System 1, all the controls not related to the SH101 are dimmed. Others take on new, unlabelled roles that you learn by trial and error. For example, the LFO Key Trig button performs the same three functions as the SH101’s Envelope Trigger switch, with the ‘Gate & Trig’ option indicated by the button flashing. Since there’s no second oscillator, the mixer is used instead to set the levels of the individual waveforms: square, sawtooth, sub oscillator and noise. While not as nice as a properly labelled panel, you can cope with it in practice. More limiting to A/B comparisons was the shortened keyboard — even losing half an octave hurts more than you might expect.

Generally the oscillator sounded authentic and is capable of fat, flappy sawtooth bass and typically hollow square waves. There were odd giveaway warbles at the highest pitches, but far less than in the System 1 and in typical use I had no complaints. Comparing filters was less clear cut. Either because it’s a knob, not a slider, or more likely because there’s a noticeable ‘smoothing lag’, the virtual 101’s response didn’t match the real thing. The smoothing process ensures no stepping is audible, from the hardware at least. (Adjust with a mouse and the increments are obvious). The greatest differences between real and virtual 101 were heard at high resonance. Where you dream of the plummy, fuzzy tones of the 101, what you get in the plug–out version is a harder and more edgy signal. If resonance is kept well away from maximum, the filter sounds not bad at all.

Later, I compared envelope speed and modulation, finding the LFO’s noise waveform at the last position on the switch (labelled RND). While at the greatest amounts the effect of noise modulation was slightly more abrasive than my 101, once you know the score it’s easy to get decent results. The other waveforms handled as expected, except that sample and hold didn’t lock to an incoming clock signal, as the 101’s does. Hopefully that’s something that can be added later because clocked S&H is a brilliant addition to a 101 arpeggio.

Eventually, I couldn’t deny that the plug–out version can sound like an SH101 a lot of the time, but it doesn’t achieve this feat without transitions that shake the illusion like an old Dr Who set. In contrast, a 101 always sounds like a 101. Apparently, Roland are considering an optional ‘purist’ version closer to the simplicity of the original (ie. single envelope, no bi–polar controls or effects). And perhaps to silence old campaigners like me, there’s a hint that the sequencer could appear in the future too. If the extra buttons also materialise, it’ll be incontrovertible proof that ACB is magic.

Conclusion

Classic analogue synths are usually revered for two reasons: their sound and their interface. The System 1 is capable of a generous range of analogue sounds and I suspect few will care whether there’s circuitry or code inside. Sure, the mask slips when some parameters are pushed too far, but thanks to a wealth of knobs, buttons and sliders, this is a synth that’s highly enjoyable to interact with regardless. Apart from its meagre patch memory and limited polyphony, the System 1 holds its own against Roland’s previous top virtual, the JP8000.

On the other hand, I found the SH101 plug–out was best appreciated when it was spared the indignity of comparison. If it weren’t for Roland’s bold claims (and the missing sequencer) I’d have enjoyed it far more because once you get past the 101 fixation, it’s a classy–sounding synth and a pleasant alternative voice to the System 1. It didn’t help that the keyboard and performance controls chosen were no match for those of the original. However, I can see how the requirement for a very minimal live rig could render them acceptable.

The plug–out concept is loaded with potential and while the SH101 is an exclusive treat for the owners of the System 1, subsequent plug–outs should be available separately and individually. If the idea proves successful, perhaps it will pave the way for more hardware in the form of a larger controller with standard keys.

A good engineer can tweak and modify ageing analogue synths many years after they are made but when it comes to software–based instruments, there’s usually a ‘development window’ in which bug fixes and new features can be added. When this window closes, remaining niggles have to be endured. Ongoing support is therefore going to be crucial to the success of the Aira range.

Ultimately, the System 1 today is an affordable, giggable synth that has two takes on modelled analogue sound, both of which sound good. It comes with Roland’s USB Audio/MIDI functionality, scope for a role as a control surface and the ability to host future plug–outs. Despite a few misgivings, it’s a worthy addition to the Aira collection.

Alternatives

If polyphony is important, most virtual analogues offer at least eight notes — and longer keyboards. However, many of the System 1’s rivals are considerably larger or more expensive. There are now plenty of monophonic genuine analogues around, and if you prefer a keyboard with velocity and aftertouch, plus a great synth engine and plenty of patch memories, Novation’s Bass Station 2 is one of the best matches, but there’s also the Korg MS20 Mini and Arturia Minibrute, each with their own unique selling points. Finally, if Total Integration scores higher than knobs and sliders, Access’s Virus Snow might be worth a look, although it costs rather more.

Pros

- Portable four–voice virtual analogue synth with built–in effects.

- Fabulous panel that sends MIDI CCs.

- Can host further ‘plug–out’ synths based on classic Rolands. The SH101 is supplied to get you started/hooked.

- Can serve as 24–bit USB Audio/MIDI interface.

Cons

- The keyboard.

- The performance controls.

- Only four voices and the analogue modelling isn’t 100 percent convincing.

- The 101 emulation isn’t the hoped–for ‘complete reproduction’.

Summary

A tiny polyphonic synth with a creamy palette of analogue and virtual analogue sounds. It’s stocked with well–chosen controls and supplied with the modelled SH101 plug–out. Bundle in an audio and MIDI interface and the System 1 is an ideal DAW companion that can operate equally well stand–alone.