New versions of Sony's Sound Forge and, especially, the innovative SpectraLayers make possible new ways of editing recorded audio.

Back in the days of analogue reel-to-reel tape recorders, an audio editor consisted of a human being, a splicing block, a razor blade and a reel of splicing tape. Although nowadays we might smile wryly at the apparent simplicity of this setup, it was capable of making millisecond-accurate edits across two to 24 tracks. The ability to manipulate recordings by physically modifying the carrier medium opened up new creative landscapes, allowing composers to apply techniques borrowed from film editing to the manipulation of recorded audio. One of the pioneers of this approach was the Egyptian composer Halim El-Dabh, who presented his tape-based composition The Expression Of Zaar in Cairo in 1944. Although mainstream today, his use of recorded and edited audio (bounced between two wire recorders) overlaid with echo and reverb was revolutionary at the time. It has always amused me to think that whilst another pioneer in this field, Pierre Schaeffer, was developing his musique concrète in Paris in the late 1940s, a certain Lester Polfuss was, at the same time, working with similar tape-based techniques in the service of popular music.

Although the basic edit functions of Select, Copy, Cut and Insert (and Loop) date back to those early days, the development of the computer-based DAW over the last 20 years or so has enabled us to manipulate sound in ways far beyond the capabilities of even the most sophisticated hardware-based equipment. Fantastically capable though a modern DAW is, though, its operation is optimised more for multitrack recording and mixing. For many editing and sound manipulation tasks, a specialist editing program often offers easier, faster and more elegant ways of achieving the desired outcomes.

Sound Forge showing the Workspace: Frg.001 is a file in the new Project format. 'New Layer' is an import from SpectraLayers. 'Phonofiddle' is a file being edited in Sound Forge.

Sound Forge showing the Workspace: Frg.001 is a file in the new Project format. 'New Layer' is an import from SpectraLayers. 'Phonofiddle' is a file being edited in Sound Forge.

Sonic Foundry's Sound Forge was one of the very first specialist, professional-level waveform audio editors developed for the PC and, along with their other audio and video software products (including Acid and Vegas), was sold to Sony in 2003. Over the last 10 years Sony have continued its development: this year saw the launch of the first Mac version, and they have now released version 11 of Sound Forge Pro for Windows.

Alongside Sound Forge Pro 11 comes a new version of SpectraLayers Pro. Developed by the small French company Divide Frame and published by Sony Creative Software, SpectraLayers Pro 2.0 brings to audio editing a spectral approach borrowed from photo editing in much the same way as waveform editing was originally borrowed from film editing.

So, given the capabilities of a modern DAW, what are we to make of a suite of two separate, specialised programs neither of which are multitrack recorders, which don't have a single mixing console between them and which are optimised specifically for the editing and creative manipulation of already-recorded audio? Actually, quite a lot...

Sound Forge Pro 11

Sound Forge Pro 11 (or SFP11, if you'll excuse the contraction) is a simple-to-use, but extremely deep and complex waveform-based audio editor, and many of its features might only be needed by advanced, high-level users. This means that not only does the manual take 61 pages to give you a sufficient overview to get started on using SFP11, but that the full functionality requires 398 pages to describe. If you want to delve deeper than space here will allow me to, the full manual can be found online at www.sonycreativesoftware.com, where you'll also find some excellent webinar-style tutorials. If you're new to Sound Forge itself, check out our reviews of its previous incarnations to get some background information (see 'Previous Reviews In SOS' box).

SFP11 comes with the expected catalogue of new features, improvements and updates, several of which deserve special mention. The most important upgrade is that you can now work in a project environment within SFP11. If you use Acid or Vegas you'll be familiar with the concept of organising the files that make up a track inside a Project. A SFP11 project '.frg' file is somewhat different in that it is not a collection of files, but rather a collection of pointers to the source files for the project. Saving a project creates both the '.frg' file and a folder containing copies of the media files, together with all the temporary files created whilst working on the project. This means that a project can be created, edited and saved without any changes being made to the original source files. Even better, there is also the facility within the project file to undo any past operations, including those occurring before the most recent save point.

Once all editing has been completed, the '.frg' file is used to render the project's media files to produce the final output file(s). Saving the project path information with the rendered file means that you can easily return to the source project to make any necessary modifications, should you use that rendered file within another SFP11 project. If you happen also to be an Acid or Vegas user, embedding project path references means that, should you use a media file from those applications in a SFP11 project and need to edit it, you can open the source project in its associated application directly from SFP11 via the Edit Source Project shortcut menu.

Although this is not a new feature, it is worth noting that the facility to save the entire on-screen layout as a Sound Forge Workspace '.sfw' file enables you to recall complex editing scenarios with all file windows restored to their previous sizes, magnification and positions on reopening. Cursor positions, custom views and the plug-ins in the Plug-In Chain are also restored.

The Plug-In Chain window has also been improved and is now modeless, allowing you to click away from it at any time to adjust your selection or to apply the effects to a different data window without having to close the Chain. Although the Chain can feel slightly clunky to operate, for my money, the ability to link up to 32 DirectX and VST plug-ins into a single chain, to preview them all simultaneously in real time (computer processing power permitting) and then to save that chain for later recall more than makes up for the minor inconveniences. Adding to the already extensive list of Sony plug-ins already bundled with SFP11, iZotope's highly regarded Nectar Elements vocal processing package is included in this release, as are their Declipper, Denoiser and Declicker audio repair and restoration tools.

Although Sony take great pains to point out that SFP11 is not a multitrack editor, its recording workflow has been upgraded and it is now a quick and simple process to record up to 32 tracks simultaneously from any active window via dedicated Arm and Record buttons. Available sampling frequencies range from 8 to 192 kHz, and the existing range of 8- to 32-bit word lengths has been extended to include 64-bit floating-point too. Since there is no on-board mixing console with track-by-track EQ and dynamics, you're not looking at a DAW equivalent here, but for capturing multi-channel audio live or for transferring, for example, two-inch tape 24-track recordings to SFP11 for restoration, this is an extremely useful feature. Improvements have also been made in the record and playback routing of connected audio interfaces under Preferences.

Useful improvements in event editing are a new ability to split an event at a region boundary and the addition of support both for moving markers, regions and envelope points and for automatic ripple editing of downstream events. In SFP11, a region is a marked area of time inside an event, and an event is created whenever either audio data is cut, copied, pasted, inserted or mixed into a window, or a selected section inside an event is processed.

There are other less eye-catching, but no less important, improvements in SFP11. However, from a sound-design perspective at least, the most significant news is the addition of support for transferring audio data (entire files or selections) freely between SFP11 and SpectraLayers Pro 2.0, which enables you to edit audio in both the waveform and spectral dimensions.

SpectraLayers Pro 2.0

SpectraLayers Pro 2.0 is a significant update on the first version of SpectraLayers Pro, originally reviewed in the October 2012 edition of Sound On Sound. Unlike SFP11, the Mac and Windows versions of SpectraLayers Pro 2.0 (SLP2 if you'll again forgive the contraction) are identical in both operation and screen layout. Fortunately, SLP2 is considerably less complex to work with than SFP11, and so its manual is a more manageable 76 pages, though I felt that it didn't really do justice to some of the advanced features contained in the program.

SpectraLayers Pro 2.0 is a significant update on the first version of SpectraLayers Pro, originally reviewed in the October 2012 edition of Sound On Sound. Unlike SFP11, the Mac and Windows versions of SpectraLayers Pro 2.0 (SLP2 if you'll again forgive the contraction) are identical in both operation and screen layout. Fortunately, SLP2 is considerably less complex to work with than SFP11, and so its manual is a more manageable 76 pages, though I felt that it didn't really do justice to some of the advanced features contained in the program.

As its name suggests, editing in SLP2 is based on the manipulation of the spectrum of frequencies contained in the audio file and, during the editing process, the audio data is organised in layers, in a manner analogous to photo-editing software. You can either build sounds up in layers, or break down the constituent frequency bands of a single recording into multiple layers, following which you can then carry out further editing in the frequency domain on each individual layer, apply VST plug-ins and finally reassemble, remove or break down these edited layers to create new sounds.

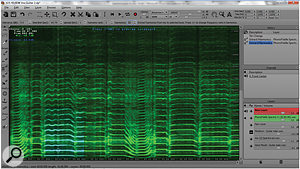

The frequency spectrum of a solo phonofiddle displayed in SpectraLayers. The first 10 harmonics have been selected using the second harmonic as the detection harmonic. You'll notice that there are approximately 25 frequencies in the full spectrum.

The frequency spectrum of a solo phonofiddle displayed in SpectraLayers. The first 10 harmonics have been selected using the second harmonic as the detection harmonic. You'll notice that there are approximately 25 frequencies in the full spectrum.

The list of new features in SLP2 not only addresses many of the criticisms levelled at the original SpectraLayers Pro but also adds significant new functionality. First off, a complete rewrite of the spectral engine is said to have significantly improved performance, particularly when viewing spectral graphs, using tools and processing spectral data. A new looping function allows the audition of selected periods on the timeline (full-frequency or band-limited) and there are also new channel mixing options in SLP2 when resampling a track that is being imported into a project with a different sample rate.

The extraction of unwanted noise as part of the spectral editing process is enhanced by a new, one-click command that removes a noiseprint from the entire target layer. The addition of the Shape editing tool makes extracting drum sounds (in particular) easier, as a point and click on a hit will pull it over to a new layer.

For me, the two most exciting new features in SLP2 are the Spectral Casting and the Spectral Molding (sic) functions, both of which are not only unique to SLP2 but also offer the most exciting basis from which to launch into sound design and manipulation. In Spectral Casting, the frequency signature of one layer is 'cast' over that of another and the target layer then consists of the second sound minus those parts of the frequency spectrum where there was an overlap with the first sound. Spectral Molding does the opposite, in that only the overlap with the frequency spectrum of the 'moulding' sound is left in the target layer. Since the relative levels and polarity of both layers can be adjusted post-processing, you have the opportunity to get very creative indeed.

SLP2 supports VST plug-ins and therefore allows you to carry out a fair amount of signal processing directly, but the interoperability between SLP2 and SFP11 opens up a new universe of creativity for sound designers. The final update readies SLP2 for the MacBook Pro's Retina display — which simply makes that 15-inch MacBook even more of a personal must-have than it was last week!

Forging Ahead

A complete overview of the functionality contained in SFP11 would be impossible in a review five times this length, but I will pick out some highlights that particularly appealed to me. The editing functions in SFP11 are, for my money, beyond reproach. Its ability to import a wide range of audio and video file formats in addition to the more usual WAV and Broadcast WAV files is a huge bonus. Naturally enough, even though you are given a thumbnail timeline, SFP11 doesn't edit video data. However, you can import a video file, edit and add to its audio and save it at 720p and 1080i in HDV, AVI and WMV formats. You can also load a track directly from a CD, and SFP11 can contact the Gracenote database to obtain the file's metadata automatically.

A nice touch when loading files is that you can have an automatic preview of the audio in that file. Once you've imported a file, or recorded one directly to SFP11, the ease and speed of editing audio are several light-years away from my old editing block and razor-blade days. Splitting a file into separate events and marking regions inside these is the work of seconds, no matter how many channels are involved. Duplicating part of a file can be as simple as highlighting a selection in the active window and dragging it onto the workspace, where a new data window containing the duplicated data is created automatically.

In addition to chopping and changing your audio around, SFP11 also allows you to process your audio in several ways. To give you a few examples, you can change bit depth, convert mono to stereo or vice versa, reverse it, resample it at a different frequency, time-stretch it whilst also changing pitch and formants to reduce the 'chipmunk' effect and, of course, modify the volume level either directly or by normalisation.

Once you've got the audio edited up as you want it, you can then move on to adding effects. A range of Sony's own time-domain and dynamics effects can be accessed directly, and these, together with third-party VST and DirectX plug-ins, are also supported through the Plug-in Chain, where up to 32 effects can be chained together and combinations saved. The two stand-out Sony effects, for me, are the Acoustic Mirror convolution reverb and the Wave Hammer compressor/volume maximiser. The range of indoor and outdoor space impulses (with a picture of the sampled space) available in Acoustic Mirror should satisfy almost every requirement — there's even a binaural HRTF selection. Should you happen to have the perfect bathroom next door, you can also use the included test tones to create your own impulses. Wave Hammer is a fine stereo look-ahead compressor/peak limiter that does exactly what it says on the tin without fuss. For most editing tasks, I found the Sony effects were more than good enough, but the ability to bring in third-party DirectX/VST effects when that little something extra was needed was just so useful.

The Acoustic Mirror convolution reverb is a highlight of Sound Forge's effects arsenal.

The Acoustic Mirror convolution reverb is a highlight of Sound Forge's effects arsenal.Setting up a Plug-in Chain is the one process in SFP11 that I think still needs a bit more reworking. Currently, you open the chain under the View menu, add the required effects, adjust and automate them as required and then save the chain for later recall. To apply the chain, you don't use the Effects menu (this only accesses single Sony effects), but the FX Favourites menu, where you then select Apply Plug-In Chain and select your preferred chain from the list of saved chains. To add automation to an effect on a file, you have to select each automated parameter and apply its individual envelope via the Insert menu. Personally, I think this is a bit of a nine-day camel ride, navigation-wise, but at least it works.

Then there's the functions under the Tools menu that should be highlighted: the audio restoration options, the batch converter that lets you apply an effect or plug-in chain, a process such as resampling or file format changes, or add metadata to multiple files simultaneously and save the outputs. I can't miss out SFP11's Red Book CD mastering capabilities and the built-in track/disc-at-once CD burning facility — even though CD Architect 5.2 comes as part of the bundle — or the fact that making up loops for Acid or working with samples from various sampler formats (including MIDI sample dumps, DLS, Gigastudio/Gigasampler and SoundFont 2 files) is really easy, or that using iZotope's audio restoration tools made turning LP tracks into MP3s a real pleasure.

Finally, alongside its ability to interface with many other DAWs as their wave editor, there's SFP11's seamless file exchange with SpectraLayers 2.0...

Layer Cake

I've been editing audio for almost as long as I can remember — from tape and scissors, through edit blocks and razor blades, past the days of bouncing from DAT to DAT up to digital audio editors similar to Sound Forge Pro — and I have never, ever been as excited by a program as I have been by SpectraLayers Pro 2.0. Spectral editing in itself isn't new, but the layering concept alluded to in SLP2's name adds a concept familiar from web site construction and photo-editing software. If you're at all familiar with a program such as Adobe's Photoshop, you'll be able to imagine what some of the possibilities of applying this concept to audio could be. Imagine being able to isolate a detail — in the case of SLP2 it's a time/frequency selection — and edit, manipulate it or use it independently of the source audio.

Whereas in a conventional audio mix each layer is additive, in SLP2 a layer can be either additive or subtractive, depending on its polarity and relative volume. As an example, you can remove unwanted sounds such as noise, clicks, squeaks or spill from other sources by isolating the frequencies that make up the unwanted sound to a new layer and then reversing its polarity so that only those frequencies cancel out. If you only want to reduce them in level, you'd change the volume of that layer so that cancellation was not complete.

Like Sound Forge Pro 11, SpectraLayers Pro 2.0 can act as an external editor for a wide range of DAWs and computer-based sampling packages, and will load a wide variety of audio file formats, although video files cannot be imported. As in SFP2, the SLP2 project environment allows for non-destructive editing of the original source file.

Once audio is loaded into a layer, you'll see the frequency displayed on the vertical axis and time along the horizontal axis. Zooming in, you'll begin to see the frequencies and their harmonics within each individual notes as horizontal lines. Naturally enough, where multiple notes occur simultaneously you'll see a stack of these zebra-skin-like lines. To help display these lines clearly, there are controls analogous to the gamma, hue and contrast controls of a photo editor. The display can be zoomed on both axes, so you can get down to a very high level of detail. To aid visualisation, the frequency display can be pulled out to display in '3D'. In contrast to the Celemony Melodyne DNA Editor, the isolation/extraction process is completely manual, which makes accurate extraction of a vocal or guitar part from a mix a time-consuming (and sometimes impossible) task. Having said that, the tools that are provided in SLP2 do work well, and the results that can be obtained with patience and skill are extremely impressive.

The extraction tools in SLP2 work similarly to the tools in a paint program, in that they highlight the area or frequencies being extracted. The most interesting of these is the harmonic extraction tool, which picks up the (other) harmonics of a selected fundamental or up to fifth-harmonic frequency. Fortunately, since frequencies to be extracted have to be selected manually, these tools can be adjusted to maximise their effectiveness in a given situation. Extracting unwanted broadband noise to a new layer is a different procedure: you 'paint' over a representative section of noise to register it, before that register is extracted automatically from the entire layer.

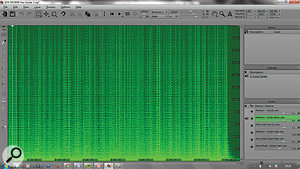

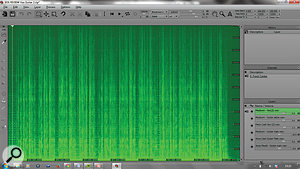

An example of what's possible with SpectraLayers' new Casting feature. The topmost of these screen captures shows a recording taken from the undersaddle pickup on an acoustic guitar. The centre screen shows the vocal mic recording, with guitar spill. By 'casting' the one on the other, nearly all of the guitar spill can be eliminated (lower screen).

An example of what's possible with SpectraLayers' new Casting feature. The topmost of these screen captures shows a recording taken from the undersaddle pickup on an acoustic guitar. The centre screen shows the vocal mic recording, with guitar spill. By 'casting' the one on the other, nearly all of the guitar spill can be eliminated (lower screen). Once you have your layers isolated, you can apply VST effects directly to them from within SLP2. A further range of tools allows you to directly modify the frequencies in a file, to draw new versions, to clone them, to move them into other layers or up and down the frequency spectrum and also to add noise, should you want to. While exploring VST effects I discovered, although the manual doesn't appear to admit it anywhere, that whilst the Mac version of SLP2 is 64-bit with native 64-bit VST support, the Windows version is 32-bit. This means that you'll need a bridging program such as jBridge in order to run your 64-bit VST plug-ins in SLP2 under Windows. Another possible limitation is that SLP2 does not natively support sample rates higher than 96kHz or word lengths above 32-bit, though it can resample a 192k/64-bit file coming in from SFP11. Nor can it create a project with more than two channels, though multi-channel files can be loaded.

The vocal mic recording, with guitar spill.

The vocal mic recording, with guitar spill.This brings us, finally, to SLP2's killer features: Spectral Casting and Spectral Molding, which work in a totally new and innovative fashion.

Cast Of Thousands

To illustrate how these features work, the screenshots show a recording where I had a miked vocal track with acoustic guitar spill, a miked acoustic guitar track with vocal spill, and a DI'd recording of the guitar's undersaddle pickup. When the tracks were played together there was a small amount of phasing in the guitar sound that I wanted to get rid of.

Here we have the recording of the miked acoustic guitar, with vocal spill. The lower screen shows the results of 'casting' this with the vocal track to eliminate this spill.

Here we have the recording of the miked acoustic guitar, with vocal spill. The lower screen shows the results of 'casting' this with the vocal track to eliminate this spill. Spectral Casting removes the frequency overlap of the 'cast' layer from the target layer, so I cast the vocal track with the piezo guitar track, and this removed most of the acoustic guitar spill from the vocal track. Of course, the pickup signal didn't exactly match the miked recording, but it was more than adequate. Exporting this layer to SFP11 let me clean things up with a noise gate to a satisfactory level and, had it been necessary, I could have got it even cleaner with a bit of eraser work once I got it back into SLP2. Mixing the guitar track and the 'cast' vocal yielded a very good result, which I could have improved on with a bit more care.

Spectral Molding is the obverse of Spectral Casting, in that instead of cutting a space in the target layer corresponding to the overlap frequencies, it cuts out the overlapping frequencies in a way analogous to a pastry cutter. I managed to achieve somewhat better results than I did above by gently 'moulding' the guitar track with the cast vocal set at a lower level, thus creating recesses rather than holes in the guitar track's frequency spectrum. The vocal then slotted neatly into these when the moulded guitar and cast vocal tracks were mixed together, giving an altogether better-sounding result.

The vocal then slotted neatly into these when the moulded guitar and cast vocal tracks were mixed together, giving an altogether better-sounding result.

In this example I was working on an entire track with problems, but more conventional applications of this technology might be lightly casting a small section of a final mix with the corresponding part of the vocal track where a couple of words in a final mix just need lifting a bit or — and perhaps more excitingly for sound designers — moulding a sound with another sound to create a new sound that hasn't been heard before. Just thinking about what could be created using sounds from my sample libraries does my head in!

Final Thoughts

The Sony Creative Software Audio Master Suite is a very impressive software collection, and its two constituent parts — Sound Forge Pro 11 and SpectraLayers Pro 2.0 — are highly specified, professional-level programs that will, between them, handle any audio waveform or spectral editing, restoration or manipulation task I can think of. The seamless interchange of audio files between these two programs opens up enormous possibilities for sound design and sample and loop creation and manipulation. Both programs will also interface easily with a range of DAWs and samplers, and this overall interoperability opens their potential user base right up — from broadcast, film and recording studios to theatre sound designers, effects, sample and loop creators and virtually anyone who needs to edit audio.

Sound Forge Pro 11 is one of the very best waveform editors available today, but it is SpectraLayers Pro 2.0 that offers, to my mind, the most exciting potential for the future. Editing in the frequency domain is an art that is now in its infancy, and the possibilities inherent in the ability to work visually on the harmonic and spectral components of a sound are going to take the art of sound synthesis and manipulation to places that Halim El-Dabh and Pierre Schaeffer could only dream of.

Alternatives

There are a number of other well-featured waveform editors for Windows, including Adobe's Audition and Steinberg's Wavelab. There are also packages that do spectral editing, including iZotope's RX and Magix's Spectral Cleaning add-on for Samplitude, but none offer the layer-based approach employed here.

Previous Reviews In SOS

Sound Forge Pro Mac: February 2013

Sound Forge Pro 10 & 9 for Windows: February 2010 & June 2007

/sos/feb10/articles/sfpro10.htm

/sos/jun07/articles/soundforge9.htm

SpectraLayers: October 2012

Pros

- A superb, professional-level audio waveform editor for the Windows platform.

- Useful operational improvements compared with the previous version.

- The new project environment allows the non-destructive editing of source material.

- Can be integrated with most DAWs and samplers as a wave editor.

- Integrated file exchange with SpectraLayers Pro 2.0.

Cons

- Plug-in handling, though much improved, still needs work to match the level of the rest of the program.

Summary

For Windows users, Sound Forge Pro 11 represents a very worthwhile update to a high-quality editing package, with the new non-destructive project environment offering real improvement in terms of flexibility.

information

SCV London +44 (0)208 418 1470.

Sony Creative Software +1 800 577 6642.

Test Spec

Sound Forge Pro 11.0 build 234 (Windows).

SpectraLayers Pro 2.0.21 64-bit (Mac); 2.0.22 32-bit (Windows).

Apple 27-inch iMac (2010) with 2.8GHz Core i5 CPU and 20GB RAM, running Mac OS 10.8.5.

HP Pavilion laptop with 2.27GHz Core i5 CPU and 3GB RAM, running Windows 7 Home Premium 64-Bit SP1.