A single sound open in a window, ready to be edited. Common procedures are available from the drop-down menus under Process and Effects. VST and DX effects can be called up from the Plug-in Chainer tool highlighted by the cursor.

A single sound open in a window, ready to be edited. Common procedures are available from the drop-down menus under Process and Effects. VST and DX effects can be called up from the Plug-in Chainer tool highlighted by the cursor.

Sony have opened their Sound Forge editing software up to new horizons with support for VST plug-ins and the ASIO driver protocol, and improved its usability with batch processing and a new scrubbing tool.

Everyone needs a stereo audio editor. It's not that you can't accomplish many of the same tasks using your Digital Audio Workstation (DAW), but it is a lot more elegant to use a hammer to drive in a nail than the flat side of a wrench. Just because it can be done, doesn't mean it should be. For many sound jobs, a stereo editor is that hammer, making the given task easier and faster. Sound Forge was one of the first professional audio editors developed for the PC, and was last reviewed by Sound On Sound when version 6 appeared back in 2002. In the intervening years, Sony have bought Sonic Foundry's entire line of audio and video software, including Vegas and Acid, updated them all, and have just released version 8 of Sound Forge. It is high time to take another look at this PC staple.

Three Of The Best

There is, of course, the usual laundry list of improvements, but three updates really stand out. Back in 2002, Martin Walker's review of SF v6 lamented the disappearance of CD Architect, which had been included with previous versions of SF. Well, it's back. Granted, CD burning is no longer the mysterious alchemy it was right after the millennium rolled around, when one was as likely to add to the toaster collection as get a playable CD. Still, CD Architect is a professional-grade tool and a step up from the software that comes bundled with every computer or CD burner these days; see the CD Architect box for more details. There is even an Export to CD Architect command in SF8, which automatically opens CD Architect and puts the sound files into the media browser.

The second major update in SF8 is ASIO driver support, which means no more switching preferences in your soundcard drivers to WDM, or having to listen to a sound file over computer speakers. If your system uses ASIO, SF8 can use the same soundcard and monitor chain as the rest of your computer music software. Sound Forge should have had this capability all along, so I'm not sure whether this is as much a plus as simply dispensing with an anachronism, but better late than never.

The third major improvement is VST plug-in support. Again, this should have been done before the dust settled in the battle between Microsoft's Direct X plug-in standard and the universally accepted VST standard, but it is still a very welcome addition. Certainly SF8 's included effects are not to be sneezed at, but most musicians and engineers have VST effects on their computer, ranging from the free sort found on the Web up to the ones that linger on your credit card. If you are anything like me, these effects include several favourite mastering tools. As one of the main reasons for having a stereo editor is mastering, finally being able to use these VST processors is a major plus for SF8. Before, I was forced to switch back to my DAW to apply my favourite VST finalising, which is not the quickest way to polish a track.

Previous Sound Forge Reviews In SOS

- Sound Forge 6

www.soundonsound.com/sos/sep02/articles/soundforge.asp

- Sound Forge 5

www.soundonsound.com/sos/nov01/articles/soundforge5.asp

- Sound Forge 4

www.soundonsound.com/sos/1997_articles/mar97/soundforge4.html

- Sound Forge 3

www.soundonsound.com/sos/1996_articles/may96/soundforgev3.html

Scrubbing & Scripting

Other updates to SF8 concern the ergonomics of using the program. Sony have added a scrubbing tool just like the one in Vegas, which can be controlled by a mouse or assigned to a jog-wheel controller. It scrubs sound and video forward or back, slow or fast, and in any combination thereof. Double-clicking with the mouse allows you to write in the rate of playback, and for those who prefer to keep their hands on the keyboard, the letters 'J', 'K', 'L' and the Ctrl key can replace mouse control. The scrubbing tool will be a major upgrade for many users: while space-bar play/stop and the virtual Play, Record and Stop buttons are more often used in the typical audio job, the scrub tool is great for finding precise edit points. It might not be as tactile as 'rocking' the reels of an analogue recorder, but it gets the job done just the same, and it is a lot faster than an analogue deck when finding the next edit point. The different sections of a song might be easy to discern in a multitrack DAW by the start of a backing vocal or a discreet hit, but masters of today's overcompressed mixes often look like a straight-edge ruler plopped down in the middle of a stereo editor. Fast-forwarding while listening is often the quickest way to find, say, the second chorus, or any other edit point.

Sony have also added customisable keyboard mapping for those who prefer their fingers never to leave the computer keyboard. Under Preferences, a whole page is devoted to setting up keyboard commands, as well as importing and exporting them. If you have no excess cranium capacity left for yet another series of keyboard commands, you can simply match Sound Forge 's keystrokes to those of your DAW. The Batch Converter in action: metadata can be written to any or all of your files.

The Batch Converter in action: metadata can be written to any or all of your files.

New efficiencies also come from Sony's Batch Converter and Scripting. The Batch Converter is as simple as it sounds. Of course, one can do more than convert batches of sounds to a different format with it, but other processes are well laid-out and easy to understand. From Tools, choose Batch Convert and a separate window pops up. There are five tabs. 'Files to convert' is the first tab. Choices include single files or entire folders, which is simple enough. The Process tab inserts any effects to be applied during Batch Convert, making it an easy way to dither mixed files down to 16-bit for CD, turn WAV files into MP3s, or master a CD's worth of songs all at once with the same chain of effects. The Metadata tab embeds your choice of information with the file, so that record exec can't lose your name and phone number as long as he has the CD. Once a batch job is ready to go, use the Save tab. If a deadline is looming, you can keep an eye on the process in the Status tab. The whole is very simple, very neat and very functional.

Scripting provides similar functions for more esoteric tasks. There is a list of common jobs, such as normalising and rendering to formats, cropping and fading, and modifying summary info (for when the lead singer finally quits the band for good). Sony have also thoughtfully included an editor for writing and modifying scripts. At the Sony site (http://mediasoftware.sonypictures.com/), SF users can exchange scripts or tips. Along with the disclaimer about downloading someone else's scripts — after all, scripts can change and erase files on your hard drive! — the forum moderator had already supplied a couple of bug fixes and some requested scripts. I wouldn't depend upon Sony's moderator for writing a script if I had to have it today, but it is reassuring to know that a week after SF8 's release there was already some good stuff in the forum. The above features may turn out to be most useful for major studios or big post-production houses, but I, for one, never complain about being able to play on the same field with the big boys when at home.

CD Architect 5.2

Today, burning CDs comes as standard on computers, but this wasn't always the case, and CD Architect was one of the first readily available CD-burning programs. There are still a couple of things that make CD Architect a more professional tool than most bundled software. You can apply any effect to all tracks to be burned, or just to a single song. New in 5.2 is support for CD Text, allowing the latest CD players to display song title and band name as your music plays. Song lists can also be exported or printed from CD Architect. Most of these functions can be done in SF8 itself, so they might seem redundant, but if you've ever wanted to get the fade between songs just right, CD Architet allows you to open up two tracks and apply different fade shapes to each song. Say bye-bye to the frustration of automatic crossfades.

Mirror, Mirror, In The Hall

How do you get to play Carnegie Hall? Practice using convolution reverb. But seriously, convolution reverb is the latest and greatest method of adding natural reverberation to a dry sound. Paul White's leader in SOS January 2005 related how he had replaced his hardware effects boxes with computer-based convolution reverb as part of simplifying his studio, and Martin Walker covered the ins and outs extensively in the April issue (www.soundonsound.com/sos/apr05/articles/impulse.htm). It doesn't hurt, of course, that convolution reverb sounds good, too. Convolution reverb can be thought of as 'sampling' an acoustic space, within which a sound can be virtually reverberated. When a sound comes out of the other side of a convolution algorithm, even an older PC can put your lead vocal into Carnegie Hall or another nice, natural-sounding space using off-line processing.

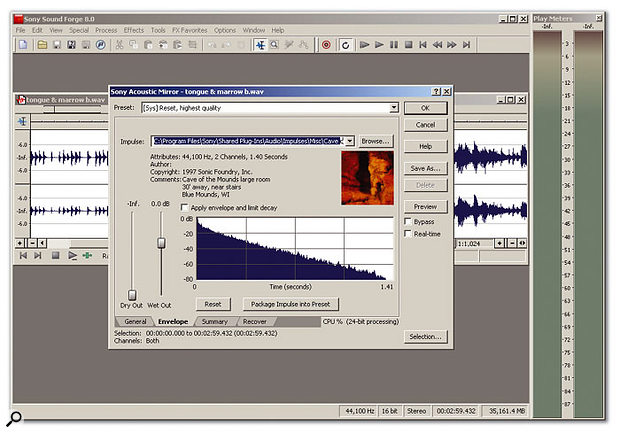

"Holy smoke, Robin! To the Batcave!" The Acoustic Mirror convolution reverb; other pages offer controls that can shape the natural reverb.

"Holy smoke, Robin! To the Batcave!" The Acoustic Mirror convolution reverb; other pages offer controls that can shape the natural reverb.

Sound Forge was one of the first programs to use convolution reverb, in the shape of its Acoustic Mirror plug-in, and this has aged gracefully. You can not only hear the reverb of the real space, but see it, too, as the included reverbs have small pictures of the spaces captured. The plug-in has a generous amount of control over the reverb itself, including delay and width, low and high-frequency shelving EQ and the application of a breakpoint envelope to the natural decay. A Preview button auditions the chosen reverb, and if none of Sony's own impulse responses fit the sonic bill, it is possible to create one that does. Included on the CD are two test tones for this purpose. To create an impulse response you simply amplify them in the chosen environment and record the result, a process which is clearly explained in the manual.

This is an invaluable tool for dialogue replacement and foley work, because if you have an impulse response for a space, you can match the characteristic of the original recording. Even if you don't plan on a career in A/V post-production, having an impulse for an acoustic recording room can save a song. Years ago, I replaced a lead vocal chorus, and the new version had to be recorded in a different room from the original. The replacement lines not only had a totally different reverb, but even a naturally different EQ. To fit them together I had to slather them in artificial reverb. The lead vocal required reverb anyway, so it didn't sound bad, but today I would use Acoustic Mirror to match the characteristics of the original room, requiring less reverb on mixdown.

It is even possible to capture the sound of a favourite compressor or other outboard device in Acoustic Mirror and use that to process a recording. And by using a plain old WAV file instead of an impulse file, you can create all kinds of special effects. It takes time to come up with something that works, but such an experiment can produce some interesting results.

Sony Sound Forge Studio

Everyone may need an audio editor, but not everyone can afford it. Along with most other manufacturers, Sony have their product line covered for this unfortunate eventuality. They retail for a fraction of the price of the full programs — SF Studio costs £69 including VAT. What goes missing along with your pounds? First, there's no support for sample rates above 48kHz. Second, there is no VST support. Third, the effects package is truncated, although most of the off-line processes remain, and there is no support for third-party Direct X plug-ins. Finally, there's no Acoustic Mirror or CD Architect, although SF Studio will still burn TAO CDs.

These might or might not be crippling problems; don't forget that up until version 8, the full Sound Forge wouldn't do VST either, even if other DX plug-ins worked. And lack of 24/96 support might not be too disastrous: after all, 16/48 was state of the art just a few years ago, and unless you already own an expensive recording studio you are not likely to hear much difference. Otherwise, Sound Forge 8 and the Studio version look and work much the same. Nobody needs to know, except you and your wallet.

Hammer & Tongs

Sony include a comprehensive round-up of processes and effects under drop-down menus. All are compiled off-line, but include a Preview button so you can hear the effect before processing. Besides the normal track and buss effects one expects to see in any audio program, there are some audio editor-specific processes such as Auto Trim/Crop, Insert Silence and Reverse. Sony's Wave Hammer compressor/maximiser is very nice, and a step above Sony's other dynamic effects, with a slightly more 'vintage' sound. It doesn't have a fancy user interface, but all the usual controls are there.

I originally thought there was something wrong with my copy of Sound Forge, since Wave Hammer came up in demo mode. It was only after perusing the Readme file that came with Sony's SF Audio Studio program (see box overleaf) that I realised installation of both on the same partition was verboten. The Readme file warned about installing SF Studio after SF, but it turns out there are problems installing SF8 after Studio, too — which is, I imagine, more likely to happen. Uninstalling SF Studio and perhaps reinstalling SF8 would doubtless solve the problem, but in the meantime I used Wave Hammer Surround from Sony's Vegas multitrack software, which defaulted to stereo processing within Sound Forge — effects from one Sony program work with the other(s). Acoustic Mirror is available in Vegas, just as Wave Hammer Surround pops up for SF. For Sony users this is another plus, and each subsequent roll-out of the different programs tends to make the whole line look and act more alike, with enhancements to one program also added to others.

For the audio engineer on the go, Sound Forge's built-in synthesis functions allow you to create test-tone sweeps and burn the results to CD.

For the audio engineer on the go, Sound Forge's built-in synthesis functions allow you to create test-tone sweeps and burn the results to CD.

However, Sound Forge is still waiting for the surround sound support that is now available in Acid and Vegas, not to mention some competing 'stereo' editors like Wavelab. Not everyone who needs an audio editor wants or can afford Vegas too! Another negative aspect to the Sony range is that their Direct X effects can't be used within other companies' software, which is a shame — Cakewalk's, for instance, get along just fine within the Sony DX environment.

Those who prefer to roll their own loops and samples will find a stereo editor such as Sound Forge invaluable. SF, of course, is designed to work hand in glove with Sony's Acid software. You can turn a hit into a one-shot sample, or Acid ise a longer file to allow its tempo and pitch to be manipulated in Acid or Acid-compatible software. One of the original uses for Sound Forge was exporting trimmed and polished samples to hardware units, and it still supports specific models from the likes of Akai, Emu and Kurzweil, as well as generic SMDI and SDS modes. SF will also produce synthetic sounds for sampling. Most samplers today, whether soft or hard, come with extensive libraries, but if you need a specific wave shape or FM sound, it can be produced inside SF and exported. The FM synthesis uses only four operators, so it is more like the Yamaha FB01 than the DX7, but it is still capable of making the distinctive sound of frequency modulation (or four-partial additive synthesis). The wave synthesizer can also produce frequency sweeps, which are perfect for checking out recording room or venue anomalies. There is even an arcane process for producing TDMF/MF tones, just like on a punch-button phone. I'm sure some designer had a good reason to include this function long ago, but I can't imagine what it was!

One or two minor things are still missing from Sound Forge 8. Sony introduced a Dim button into Vegas, where I seldom use it, and I was hoping it would make it into SF8, where I would. Sometimes, when you over-process a sound, the file redlines the meters and output. My audio interface, mixer and amplifier are all within reach, of course, but it would be quicker to limit the damage with the mouse.

In Use

As mentioned above, a DAW can accomplish many of the same functions as any stereo audio editor. So why lay out good money for another program? Well, I said many tricks, not all. Otherwise, why would your DAW have an option for exporting a sound to an audio editor?

The first job that comes to mind is mastering. SF8 does non-destructive editing, at least until the file is saved, contains a host of Sony effects, and can now use VST effects too. Once the song is mastered to you or your client's taste, it can be dithered to 16-bit, if necessary, and burned to CD using the Track at Once (TAO) CD writer built into SF8 or by exporting to CD Architect. The dithering in SF8 is first-rate, with several different presets available. Finally, there is the psychological advantage of mastering in a different program from your DAW. Close the DAW and open SF8 and you've switched hats. No more going back again to adjust the volume of that shaker sample that spices up the third verse — at least not without stopping and reopening both DAW and song. About the only function that would be quicker in a DAW is laying different files on a timeline and fading between them — it would be nice to be able to fade sounds over one another in a window directly.

Even if a DAW suffices for mastering, a garden-variety musician/engineer will find that many tasks go easier and quicker using a stereo editor. A band I had worked with wanted to swap out one song on a demo CD for another from a second. A simple enough task: SF8 can extract songs off a CD — or two CDs in this case — and automatically opens windows for the data; in this case, the three-song demo in one window and the single song in the other. Highlight the song to be eliminated, cut it and delete. Highlight and cut one of remaining two songs, save and paste to new, with SF8 conveniently opening a new window. The three songs were now ready to export, except that the new song had an unnatural ending because its reverb tail was chopped off. Either someone had trimmed it back too far or had forgotten to tick the Play Effects Tail command. Never mind — it was easy to place the cursor on the last beat, pick an appropriate, unobtrusive reverb and add it to only the end of the song. The song now faded into silence, rather than a jarring cut. Save, then burn the demo. The whole job took only a little longer than to write the description of it.

Four tracks are better than two: choose the right fade for each song or butt-splice two songs together.

Four tracks are better than two: choose the right fade for each song or butt-splice two songs together.

Another chore for which I used SF8 was stripping out the audio of a song from a video project. The singer had changed her performance, was going into the studio and wanted a copy of it so she could practise in her car. This was harder than it should have been. I had a copy of the band's promo DVD, which included a live version of the song, but none of the Sony software will load the AC3 or VOB audio portion from a DVD. This was a problem in Vegas, too, where to make even a minor change to a DVD one has to go back to the original source files. I hoped SF8 would cure this problem, but no such luck. The video loaded in fine, but no audio. (Video in SF8 is displayed as a film strip, which can be animated. In the default film strip size, the motion within the small frames looks like stop-motion animation or Gumby claymation, which is cool, but didn't do anything about the audio problem!) Fortunately, I got a hold of the DAT tape they had used, and I was able to retrieve the song from there. I simply recorded the song straight into SF, cleaned up the in and out points, resampled the 48kHz file down to 44.1kHz and burned it straight from the TAO function.

For sound design and manipulation work, moreover, SF8 is perfect. I had collected some wicked-sounding metal gates at a farm. I want sound effects for my library to add a little ominous spice to almost-finished tracks. Inside SF8, the metal screeches became ominous and more. After capturing the five-plus minutes of DAT tape in SF8, I deleted all the unwanted noises — I had also tried to record my footsteps as I tromped across a wet cow lot, but I was torn between getting a good signal and getting the mic too close to the sucking muck, and the borrowed stereo mic won out. Once the useless parts were excised, I saved the good parts and then began my Frankenstein experiments. Likely bits were pasted out for mangling. Along with the more commonplace effects, SF8 includes some esoteric sonic software. Time-stretch and pitch-shift are catered for, both at the same time if needed, and the latter includes a bend function, allowing the amount of pitch-shift to change over time — one of the presets is called Whammy Bar, which can be customised to less (or more) extreme settings. The stretch/pitch algorithms are good: although I did notice some artifacts using the Whammy Bar preset, at more sane settings they did a great job. In no time at all I had a collection of evolving sounds that were brasher and more interesting than most pads. They all reeked of metal that was twisted and distorted. SF8 includes an Undo function, of course, so when a sound went bad, I could just back up a step and try something else.

I also tried using some of the same files I was working on as impulses in Acoustic Mirror. This was the only time SF8 crashed on me, but that was because I was changing impulses while previewing the effect — Acoustic Mirror uses a lot of computer overhead, and I overtaxed my system. When I restarted SF8 after the crash, the file I had been working on was recovered and popped up in a window, ready for action.

Summing Up

Sound Forge 8 is a mature program. There are few things it won't do, given its intended purpose, and the more you use it, the more tricks you realise you can do with it. Not only does it make many tasks quicker, but its speed and ease of use practically beg you to try out new ideas. That in itself is worth the price of admission, in my book. SF8 is still no impulse buy, unless you're in a different tax bracket from most of us, but it is a better deal than ever. Even if you don't really need an audio editor and can live with your computer's basic CD burner program, Acoustic Mirror might seal the deal, if you don't already have a good reverb — you can simply export your track(s) to SF8 and add convolution reverb to taste. You could even export multiple tracks and use the Batch Converter to apply different reverbs to them. It's not as elegant as using a VST effect within your DAW, but then a VST effect won't edit your stereo masters, either.

Like its sister package Vegas, Sound Forge 8 is a very easy program to learn and use. Not having to deal with MIDI (except for sync functions) helps, of course. But if you come from the analogue recording world, or are at least familiar with cassette decks, everything is well laid-out and logical. The ergonomics of analogue recording developed over half a century or so, and there is no reason why an audio-only recording software package should try to reinvent the wheel. Sound Forge doesn't reinvent the wheel, but the additions and upgrades in version 8 make it a more perfect circle.

Minimum System Requirements

- Windows 2000 or XP.

- 500MHz processor or faster.

- 150MB hard disk space.

- 128MB RAM.

Pros

- VST support.

- ASIO support.

- Batch Converter and Scripting relieve the tedium of repetitive jobs.

- CD Architect is back, with CD-Text capabilities.

- Audio scrub tool.

- Looks and works more like Vegas and Acid.

Cons

- Won't import AC3 files.

- Doesn't support surround formats.

- No Dim button.

Summary

Sony have added functionality and flexibility to their old audio-editing warhorse while retaining the ease of use of the program. Sound Forge 8 adds much of what was missing from the early versions, other than support for surround sound formats, and for stereo editing and CD creation, it is hard to beat.

information

£299 including VAT.

SCV London +44 (0)20 8418 0778.