Microsoft’s latest OS offers potential benefits for musicians and recording engineers — but is now the right time to move to Windows 10?

Since Windows 8 was launched, there’s been a noticeable change in the way Microsoft present themselves. The burgeoning market for mobile devices, with its diversity of operating systems, has seen Microsoft’s hegemony challenged in recent years. Windows 10 appears to be the result of a massive conversation in which consistency across devices has been demanded, and in which participants have made clear that they want this OS to be serious, businesslike, sleek and powerful — yet also fun and easy to use. The nature of those requests comes as no surprise: in creative industries our focus is often on running a single (albeit demanding) bit of software very well, but the rest of the world wants Windows to do everything.

It’s almost as if they’ve thrown open the gates to the chocolate factory and CEO Satya Nadella, the current Willy Wonka, has invited everyone to talk to the Oompa Loompas like they’re real people. It’s now possible to have conversations with Microsoft employees, the very people who are developing the tools we require to use our computers efficiently and effectively. What’s more, they seem to want to talk less about Taking Over The World and more about how they can provide a stable platform that lets people do their thing. They’re genuinely excited about you doing your thing, and they’re excited about you getting excited about it — possibly because it means you won’t notice them taking over the world when the time comes, but for the first time in years, I get the impression that they’re genuinely listening. And so far, Microsoft’s response to this conversation has been encouraging: whether you’re a member of the Start Menu-resurrection cult or a touchscreen-fingering bohemian, there’s something for everyone in Windows 10.

Upgrade Or Fresh Start?

Windows 10 is available to buy for $129.99 as a fresh installation, but a free upgrade is available to anyone who’s running a genuine copy of Windows 7 or above. The upgrade process is very easy: you either wait for Microsoft to tell you, via a little Windows icon in the bottom right corner of the screen, that your upgrade is ready, or you initiate the download yourself by visiting Microsoft’s web site (www.microsoft.com/en-gb/software-download/windows10). The staggered automatic roll-out is designed to ensure the smoothest upgrade possible for your system; they prioritise systems that have the highest chance of success in upgrading smoothly. So, while you can choose to upgrade manually before being prompted to do so, there’s a higher possibility of a bumpier ride. In either case, the upgrade will replace your current system, but your files and folders will remain intact, all your software will still be installed and everything should work fine. You have the option of creating an installer on a USB pen drive or other media, an approach which can sometimes result in a slightly ‘cleaner’ OS install — but you may need to run the updater before your fresh installation, in order to generate your licence!

You have the option of creating an installer on a USB pen drive or other media, an approach which can sometimes result in a slightly ‘cleaner’ OS install — but you may need to run the updater before your fresh installation, in order to generate your licence!

Alternatively (and this is often a healthy way of maintaining a clean system), you can download Windows 10 and create your own installation media on a DVD or USB thumb drive in order to do a nice fresh installation from scratch. In this scenario, the media creation tool will tell you that you either need a Windows 10 Product Key or that you must buy a licence at the point of activation. If you want to do a fresh installation of Windows 10 for free, you’ll have to run the upgrade beforehand: the upgrade process takes your Windows 7 or 8 activation and binds it to Windows 10 and the current computer hardware, so when you then perform a fresh installation, Microsoft already know your hardware and your Windows 10 activation — sorted. In fact, via the upgrade route there is no Product Key.

Unfortunately, this means you’ll have no opportunity to move your free Windows 10 OS to any other machine (that’s not unique to Windows 10; it’s always been true of any Windows upgrade licence). Another consequence is that your Windows 7/8 licence is surrendered and replaced by the Windows 10 licence. The Microsoft license agreement states that “the upgrade replaces the original software that you are upgrading. You do not retain any rights to the original software after you have upgraded and you may not continue to use it or transfer it in any way. This agreement governs your rights to use the upgrade software and replaces the agreement for the software from which you upgraded.”

One of the big attractions of Windows 10 is that it’s essentially the same operating system whether it’s running on a phone, a tablet or a ‘serious’ computer. Furthermore, the native audio latency is much improved, making it easier in theory to compose on the hoof on a mobile device and open your project up directly on a more powerful studio machine later.

One of the big attractions of Windows 10 is that it’s essentially the same operating system whether it’s running on a phone, a tablet or a ‘serious’ computer. Furthermore, the native audio latency is much improved, making it easier in theory to compose on the hoof on a mobile device and open your project up directly on a more powerful studio machine later.

In other words, you’re not permitted to run your previous version of Windows alongside the new OS. Obviously, this is not great news for people wishing to dual-boot, or to dip their toes in the Windows 10 water before committing. However, Microsoft allow you to return to your original OS at a later date, and so the realities of how these licences will be enforced is a slightly grey area. Also, it’s worth noting that dual-booting has always required two licences (even if, in practice, most people ignore that requirement and don’t fear the imminent arrival of the licensing police).

The easiest way to create a dual-boot system with Windows 10 is to first create one with two copies of Windows 7/8, and then upgrade one of those to Windows 10. So you could see a dual-booting machine as being one where you are constantly upgrading and downgrading your software. If you want to make things easier for yourself, of course, you always have the option of purchasing a retail copy of Windows 10 with a Product Key.

If upgrading, it’s also worth bearing in mind that, with Windows 8.1, Microsoft have clarified that the OEM versions of the OS are not intended for use by individuals, personal system builders or virtual machines, but can only be used by system builders who are selling the system to end users and are willing to provide the Windows support themselves. Here’s what they said: “An OEM (Original Equipment Manufacturer) licence is tied to a particular computer system via the motherboard. It’s non-transferable so if the motherboard dies then so does the licence. You can upgrade the computer to a point and you may need to go through a manual activation process after hardware changes. The OEM version includes no Microsoft support — that has to be supplied by the system builder. The Retail version licenses the user to run the OS and so that licence can travel from computer to computer provided that only one copy is activated at a time. The retail version will usually contain both 32-bit and 64-bit versions of the OS, comes in a nice box, includes Microsoft support and is more expensive than the OEM version.” (Source: Microsoft Licensing FAQ.)

Beware buying DVD installers from eBay and other such online markets. The discs pictured here are labelled for ‘OEM’ use, which means that they’re intended for use only by computer manufacturers, not end users. These copies are supported by the computer manufacturer, not Microsoft themselves, and once installed on a PC the licence can’t be transferred.

Beware buying DVD installers from eBay and other such online markets. The discs pictured here are labelled for ‘OEM’ use, which means that they’re intended for use only by computer manufacturers, not end users. These copies are supported by the computer manufacturer, not Microsoft themselves, and once installed on a PC the licence can’t be transferred.

Automatic For The People?

For the first time in a Windows OS, updates are no longer optional. In the standard version of Windows 10, updates are downloaded and installed automatically; in the Pro version, updates can be deferred but ultimately have to be installed. It’s only in the Enterprise version that updates become optional. Initially, this seems a bit bonkers — disabling automatic updates is a traditional OS tweak, as it prevents your system being harmed by a faulty update or having your carefully installed drivers messed with. However, Windows 10 approaches these things differently. Rather than having occasional updates, service packs or ‘Patch Tuesdays’, as in the past, Microsoft will be continually revising and updating the software. Through the use of telemetry, Microsoft know a lot more about your system, and potentially have instant feedback on issues from millions of users, and so their potential ability to react to things is far greater than it has been previously.

One of the biggest causes of system instability is old drivers or unpatched software: the first question a tech-support engineer will ask a customer is whether he or she has downloaded the latest drivers, because when people complain about their systems crashing or running slowly, it’s often because they haven’t updated their systems. Microsoft want to cut through all this by keeping every copy of Windows 10 up-to-date, secure, stable and working. It’s perfectly sound reasoning but, of course, we’re all traditionally sceptical of such an approach, and it remains to be seen whether Microsoft will get this right in practice.

The automatic updates, which can’t be turned off in most versions of Windows 10, have been greeted with suspicion by the tin-foil-hat brigade, but they should enable Microsoft to be much more responsive in sorting the many problems that inevitably arise with any new OS.

The automatic updates, which can’t be turned off in most versions of Windows 10, have been greeted with suspicion by the tin-foil-hat brigade, but they should enable Microsoft to be much more responsive in sorting the many problems that inevitably arise with any new OS.

If you don’t trust them to do so, there are a couple of workarounds. Firstly, for all versions of the OS, there’s a tool from Microsoft that allows you to prevent some (not all) updates from being installed. The idea is that if something is installed that upsets your system (graphics drivers are a common culprit) you can uninstall it, run the Troubleshooter tool and prevent that update from being installed again. (More details here)

The other option is available if you’re running Pro or Enterprise versions of Windows 10, and is accessible via the Group Policy editor. Type ‘gpedit.msc’ into the Run box and navigate to Computer Configuration / Administrative Templates / Windows Components / Windows Updates and select Configure Automatic Updates and Edit Policy Settings. Click on Enabled and then, from the drop-down menu, you can select ‘Notify for download and notify for install’. This will prevent Windows from downloading any updates unless told to do so.

Microsoft knowing more about your system is, for some, a cause for concern. Everyone reads the Privacy Policy and Service Agreement files when upgrading to Windows 10, right? Well, hidden in there (or written in plain sight depending on your paranoia level!) are some statements about the sort of information they will gather from your system. Taking an extreme view, it appears that Microsoft have every right to access anything you read, type or do and use it for nefarious ends. A more conservative reading reveals that it’s mostly a collection of permissions to allow parts of the OS to function. If, for example, you want online spell-checking for web forms and Cortana (the inbuilt personal assistant/search tool) then you have to give Microsoft permission to read the words you type. Cortana is designed to make personalised recommendations and so needs to use your data, for instance your email, calendar and browser history, to anticipate your needs. Cortana is completely opt-in (ie. you’re not forced to use it), customisable and will do nothing without your agreement. Similarly, if you want to tag photos with your location you need to give Microsoft permission to know your location; if you want to carry your Microsoft account across multiple devices you need to give Microsoft permission to access your browser history, favourites, network names and Wi-Fi passwords, and so on. Microsoft also collect telemetry data on what’s installed, your hardware setup, network settings and so forth (as it has done since Windows 7 via the Customer Experience Improvement Program), and this could be vital in keeping the automatic updates free from trouble. Most of these things can be turned off in the Windows 10 Privacy Settings if you really want.

Many musicians prefer to keep their systems off the Internet most of the time, and set up for the single task of being a DAW. In that scenario, all the bells and whistles offered by Windows 10 connectivity are of little value, and the best way to reduce the intrusion of Microsoft is to create a ‘local account’. This has no connection to your Microsoft account, and it won’t sync with anything or be tracked to a particular user. If you’re not connected to the Internet then automatic updates and the collecting of data will not be an issue. So it’s completely possible to use Windows 10 isolated from all of the things you may fear. However, if being a DAW is just one of several jobs your computer is used for, then maintaining an up-to-date, fully connected, secure and integrated system is probably going to give you the best user experience.

A problem that’s pertinent to computer audio was discovered only a couple of weeks after Windows 10 launched, and could be seen as an example of Microsoft’s ability to quickly and quietly solve issues behind the scenes. It was reported by pro-audio manufacturer Sound Devices that Windows 10 would corrupt WAV files on any FAT32-formatted SD card when connected via an external USB reader — these corrupt files could not then be read by anything. Further investigation revealed that file headers were being corrupted, and that the WAVs could be recovered using a hex editor (a very messy solution!). It turned out that the problem was specific to Sound Devices recorders and was caused by the company wrongly making use of a Microsoft ‘reserved bit’ which had been unused by previous versions of Windows, but, in Windows 10, is used to tell Windows whether the file is encrypted or not. Microsoft acted immediately to identify the issue, demonstrate the cause and provide a fix, so that customers’ data is not in danger of being messed up by a third party’s mistake. Have we moved from an environment of workarounds and hopes for a fix in the next Service Pack to issues being resolved in a matter of days? That could be a really good thing, but if we all stop Windows updating and reporting data then it’s not really going to work in our favour!

What’s perhaps a little disconcerting is that Microsoft seem to assume that we’re all OK with the things they’ve decided to do to improve our user experience. There are reports that Microsoft have downloaded the Windows 10 installer files onto systems that haven’t opted in or accepted the offer of a free upgrade. They are using internal and Internet networks to deliver the installation files via a shared download, similar to peer-to-peer downloads, to improve the speed of delivery. These things may well improve the user experience but also seem rather rude and presumptuous. They have also increased telemetry on Windows 7 and 8 via a few innocuous updates in order to gather information on how well the Windows 10 upgrade would go — though this is only for customers who have already opted into the Customer Experience Improvement Program (CEIP). Again, most of these things can be disabled in Windows 10, and the updates to avoid (if you wish to avoid them) in Windows 7 and 8 are as follows: KB3068708, KB3022345, KB3075249 and KB3080149. To check whether you’ve opted in or out of the CEIP in Windows 7/8 go to Action Center / Change Action Center Settings and click the link to Customer Experience Improvement Programme Settings. In the Windows 10 Action Center you can select ‘Quiet Hours’ to disable various notifications, including the ones that typically trigger unwanted system sounds.

In the Windows 10 Action Center you can select ‘Quiet Hours’ to disable various notifications, including the ones that typically trigger unwanted system sounds.

Universal Windows Apps

One of the big advantages of Windows 10 is its ability to run across lots of different types of device. From desktops to phones, laptops to Xbox, and Surface to Hololens, everything can run Windows 10 with the same Windows Store. Developers can compile one application and have it run on whichever devices they choose. In more practical terms, this means that if you buy a music-oriented Universal Windows app, it can be available on whatever device you’re using. This has great implications for mobility and getting hold of the software you need wherever you are.

Unfortunately, there are currently very few Universal apps of interest to the musician, but Microsoft are working to change this. One of the key areas they’ve been looking at is the quality of and access to MIDI and audio systems within Windows. Microsoft’s Pete Brown gave a keynote speech at the Summer NAMM show back in July, in which he laid out all the work the company have been doing on the audio side of Windows. This included a new multi-client MIDI API which will run on every device and allow multiple applications (both Universal and conventional desktop-only ones) to access it simultaneously. It’s designed to be open to further development into other mechanisms for MIDI transport, such as via Bluetooth or over networks.

The ‘audio stack’ has also benefited from some major development, probably the best result of which is the reduced buffer size: straight off the bat, Windows 10 can boast a 15ms reduction in latency when using WDM or WASAPI drivers. Microsoft are also enabling developers to opt into a smaller range of buffers, depending on the audio hardware they are running. This means that music software using standard Windows drivers could, conceivably, get native latency levels low enough for music performance. I’ve been frustrated in the past when comparing the low latency in iPad and iPhone apps to the lag on my Windows phone and Surface, and this is presumably one reason why there are so few good music apps for Windows devices. Windows 10 goes a long way to resolving this disparity, and should make developing Windows music apps a more attractive proposition.

Another innovation is Audio Core Isolation, which directly tackles the biggest and most annoying cause of audio glitching: DPC latency. In a nutshell, DPC latency is the time a device takes to interrupt the processor and get its business done. Some devices — commonly Bluetooth, Wi-Fi and network adaptors — can take too long to interrupt the processor or hold onto the processor longer than they have to, one result of which is a stream of audio not getting the full attention of the CPU and, consequently, glitches. In Windows 10, Microsoft have created the ability to put all the audio processes onto a single core of the CPU and move those other devices to other cores, thus giving audio tasks the undivided attention of a core. This should totally remove DPC latency issues for WASAPI/WDM, and it may expand in the future to more cores and other audio APIs. It’s worth mentioning that I’ve yet to see this in action and it’s something that software developers and hardware drivers have to opt into, so it’s an improvement that may take time to make itself felt in practice — but its potential for real-time audio performance improvements is awesome. Microsoft have put a lot of work into opening up the audio engine to make it easy for developers to create modern apps that can get creative with sound, samples and synthesis. It’s heartening to see that outside the world of professional DAW software, Windows could become a music-friendly creative playground.

Of course, most serious audio-PC users already use software and hardware with ASIO audio drivers, which means much of the above may initially seem uninteresting. However, many musicians have found creative opportunities with the iPad and iPhone in the ability to make music on the go, outside the regular desktop/ASIO/VST ecosystem. The trouble has always been how to integrate something running on iOS with a Windows or OS X system. With Windows 10 and the Universal App concept, you’ll be able to use the same software on your desktop as on a Windows tablet, laptop or phone, and with a similar level of latency, regardless of whether you packed your audio interface or not. So perhaps you’ll write a tune on your phone while on the bus on the way home from work, and you’ll get home and be able to open it right up on your more powerful desktop machine — that would be rather cool, wouldn’t it?

While there aren’t yet many apps, there are a few promising examples. Stagelight from Open Labs is a good one: it’s a piece of desktop DAW software that’s also designed for tablet use. The work Microsoft have done on the audio engine, and that 15ms lower latency, mean that the virtual synths within Stagelight, when accessed on a touchscreen through the onboard sound in Windows 10, have suddenly become a lot more playable.

Compatibility

As with any OS upgrade, there’s the small matter of compatibility to consider. Because, in the grand scheme of things, it’s still fairly early days for Windows 10, you really must check the compatibility of any mission-critical software and hardware (your DAW and any other audio software such as scoring programs, and your audio interface, control surface, any DSP cards and so on) before upgrading. Some manufacturers will have tested their software or hardware thoroughly, and will perhaps even have released updated drivers. A few will have encountered problems and be working to address them (Steinberg, for instance, encountered an issue with the Quicktime player used for video playback in Cubase Pro 8). Yet others, particularly smaller developers, will not have had time to robustly test things, and you may have to take a punt. And then there’s all the discontinued stuff that’s no longer supported, and which certainly won’t be updated any time soon.

If there’s no official manufacturer compatibility statement, it’s well worth spending a bit of time searching for user reports of compatibility or incompatibility. You have to take these reports with a pinch of salt, but it’s usually possible to get a reasonable indication of your chances of success. It’s worth noting that Windows in general has long been pretty good at legacy support, and it’s somewhat reassuring on a quick trawl of the usual forums to find that some people have had success even getting long-withdrawn 32-bit hardware such as Focusrite’s Liquid Mix and TC Electronic’s Powercore DSP devices to work in Windows 10’s 64-bit environment.

To Tweak Or Not To Tweak?

Tweaking Windows to optimise it for music-production use has in the past been essential, but is usually much less so now. Windows 10 is already a stable, performance-orientated platform and requires less tinkering than previous versions. There are still a handful of tweaks that can be considered good practice for getting the best out of an audio-focused computer, but most are really only required to prevent unexpected interruptions, or if you find things are not working properly. Running DAWBench and a Pro Tools D-Verb test on a newly installed audio PC from Molten Music Technology showed that, tweaked or untweaked, there was not a plug-in’s worth of difference in performance — in other words, the performance in Windows 10 is excellent either way.

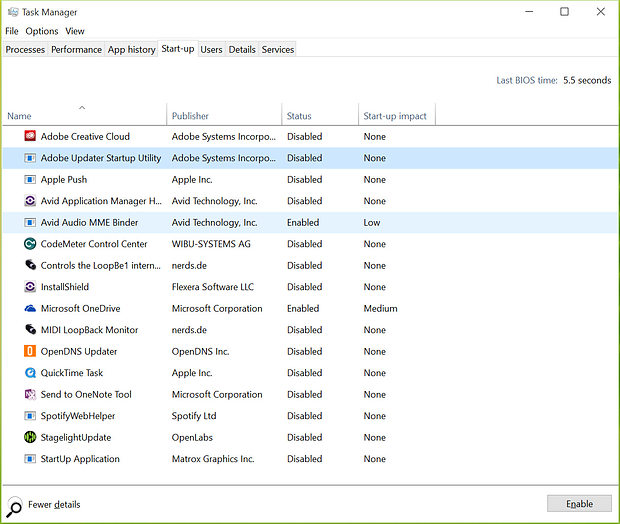

As in previous versions of the OS, if you’re experiencing inexplicable audio glitches, a visit to the Task Manager will enable you to turn off various unnecessary (to the musician) processes running in the background.

As in previous versions of the OS, if you’re experiencing inexplicable audio glitches, a visit to the Task Manager will enable you to turn off various unnecessary (to the musician) processes running in the background.

Nonetheless, should you encounter problems, it’s worth adhering to the following advice:

Turn off background tasks: This is the golden rule for running a stable DAW: don’t run unnecessary stuff in the background. Many applications like to keep a part of themselves running at all times, just in case they might be needed quickly. Common culprits are Bluetooth, wi-fi and networking software, Quicktime, Adobe updaters and graphics card utilities. Although most services, when running, have no impact on the CPU, when they are activated via a call or notification they can cause unexpected glitches. Most can be disabled in the Task Manager (available in the admin menu if you right-click on the Windows icon in the bottom left corner of the screen). You’ll need to click on More Details and then the Start-up tab, and disable anything you find there. The other place to check is the icons next to the clock; they may have options that allow you to turn them off. This can also include anti-virus, firewall and security software, though, and it’s only wise to turn these off when not on the Internet. There may also be some things that you need to leave on, such as control panels or your audio interface’s mixer software — a pinch of common sense is always helpful!

Power profile: Set the power profile to High Performance. Also available from the Admin menu as Power Options, this tweak has long prevented CPUs from clocking down or entering power-saving modes. Be aware that the effectiveness of this tweak depends on the hardware inside the computer, as most mobile processors are hard-wired so as to save power whether this option is selected or not. Note that on the Microsoft Surface and other tablets the High Performance option doesn’t actually appear, and with good reason: these devices are designed to run best on ‘balanced power’. Enabling High Performance would run other systems inside at constant high levels, increasing the heat and so triggering the throttling of the CPU sooner than when running with balanced power.

Setting Processor Scheduling to Background Services makes Windows prioritise things going on in the background over the main software applications that are in use — given that audio interface drivers are ‘in the background’ this can help eradicate problems!

Setting Processor Scheduling to Background Services makes Windows prioritise things going on in the background over the main software applications that are in use — given that audio interface drivers are ‘in the background’ this can help eradicate problems!

Processor scheduling: Switch the Processor Scheduling setting to Background Services. Windows can prioritise programs and applications or the background services running the hardware. The idea behind switching to Background Services is that this can improve the performance of some audio-interface drivers. So if you are plagued by glitches, pops and dropouts then this could be a solution.

Disable system sounds: There’s nothing worse than the ‘bing bong’ sound of a notification thundering through your monitors in the middle of a mix and. With some audio interfaces, system sounds can even interrupt the audio. Type ‘sound’ into the search bar and select the Control Panel option to bring up the Sound Properties window. Click on the Sounds tab and select ‘no sounds’ from the drop-down menu.

Disable notifications: Along with the sounds you can disable the notifications that often cause them. Open the Action Center to find a tile called Quiet Hours. Enable this and your computer will no longer notify you of anything. If you right-click the tile and select Settings, you can manage all the notifications and background apps that are enabled in the system, and even disable the Action Center entirely.

Marks Out Of 10?

So should you upgrade to Windows 10 now? It’s certainly an attractive proposition, and the ubiquity across different devices holds great promise, even if some of the benefits will only be realised as more Universal apps for music makers are developed, or will only apply to those using applications or hardware that don’t already have ASIO drivers. Despite the noises emanating from those concerned about privacy and civil liberties, I don’t think there’s anything more sinister going on with Windows 10’s data collection than with any other software system these days, and Microsoft’s approach offers plenty of tangible benefits to its users. The rapid response to the Sound Devices issue and the ‘new openness’ of Microsoft more generally also offers encouragement.

There will inevitably be a few compatibility issues in the early days, but the indications are that these are relatively few — and if you’re in any doubt (and your current system already does what you need it to), remember that the free upgrade is available for a full year, during which time most manufacturers will have had time to address any surprises that Windows 10 threw at them.

Really, then, for most users, it seems to me to be more a question of when to upgrade than if, and of whether or not to run a dual OS installation for a while, whether simply to get your bearings or to be completely sure that you don’t have any unplanned downtime. Just remember to back up your system before upgrading, that you have until next July to accept the free upgrade — and that you can always downgrade again if you don’t like it!

Telemetry: A Spy On Your Machine?

Telemetry may sound mysterious, but it’s just a term meaning the collection of diagnostic and functional information on computer systems. For some people, this reeks of Big Brother, but those fears are misplaced. It’s an industry-standard method of data collection used to improve operating systems and hardware interaction and is used by Apple in OS X and iOS, Google and Linux. In Windows 10, it is completely anonymised — it’s not tied to any user or Microsoft account. The focus of Microsoft Windows development is driven by data. If musicians and the pro audio industry all disable telemetry and updates then Microsoft are never going to see audio-orientated features being used, and this will make it more difficult to make a case for investment in those areas. It’s also telemetry that enables Microsoft to fix bugs and crashes before they hit millions of users.

Minimum System Requirements

Most vaguely modern computers will satisfy the minimum system requirements. A 1GHz or faster processor or SoC (System On a Chip) is required, with 1GB (32-bit OS) or 2GB of RAM (64-bit). The minimum display resolution is 800 x 600 pixels and the graphics card must support DirectX 9 or later and have a WDDM 1.0 or later driver. Finally, you’ll need 16GB (32-bit OS) or 20GB (64-bit) drive space.